News Blog

- Linda Stansberry

- A sign welcoming visitors to the MAC.

It’s a rainy Friday morning, but the bright yellows and oranges of the Multiple Assistance Center, tucked into the north end of Eureka next to the Pepsi distributor and Target, shine like beacons under the grey sky. Casey Crabb, deputy director of Redwood Coast Action Agency’s adult services and families in transition program, waits in the lobby. The lobby, like the rest of the interior, is painted in calm blues and greens. Behind the lobby desk is a windowed intake room, where a woman sobs as a worker hands her tissues. Residents are required to sign in and out, and their bodies are waved over with a metal detector wand when they re-enter. To protect the privacy of residents, there are no visitors allowed. The entire facility – with the exception of dormitories and bathrooms – is under video surveillance. There are few complaints, staff say. Institutional as it may be, for residents the Multiple Assistance Center is home.

Keeping things running smoothly at the MAC seems to rely as much on compassion as it does on rules. It tends to run full, Crabb says. The facility is currently able to accommodate a maximum of 40 residents and hasn’t dipped below 35 since it re-opened in July 2015. Prior to restructuring, the facility housed families, but recommendations by the consultancy group Focus Strategies led to a decision on behalf of RCAA and the county to redirect its resources into helping chronically homeless adults. There are a few stipulations: clients must be over 18, a Humboldt county resident for at least six months, homeless and willing to be housed, able to eat and bathe themselves as well as take their own medications, have no violent criminal history in the past five years and no record as sex offenders. Caseworkers will help people get government-issued identification, and county residency is often confirmed by CalFresh benefits. Clients are referred – and usually pre-screened – through Mobile Medical, Sempervirens, the Mobile Intervention and Services Team and Street Outreach Services. The wait list hovers between 50 and 80 people.

There are usually between three to four client support specialists on duty for any given shift, men and women who interact with the clients, help navigate their transition through supportive living and defuse any tension.

For many clients, the first thing they want to do when they arrive is take a warm shower. There are ADA-accessible bathrooms on each wing, and one very cherished bathtub. The spread of skin diseases such as MRSA and scabies are a chief concern by staff, who douse their hands with Purell regularly. All of the clothes of clients coming in are immediately washed, and they are given access to the clothing closet, where they can pick out new duds.

“So far there has been very minimal spreading,” says Crabb, who says that staff also do some rudimentary wound care for clients, who sometimes have open sores. Staff also take clients to the local beauty college for free haircuts on Fridays.

- Linda Stansberry

- Inside a handicap-accessible bathroom at the MAC.

“It’s all about the culture you create,” says Crabb. “They are adults. They want their space to be safe.”

Crabb admits that balancing personal autonomy with the structure that makes communal living possible is a “very delicate dance.” The most important element, she says, is rapport. Staff get to know the clients. Word leaks out to the streets, meaning that the clientele interested in housing know what they’re about and how they’ll be treated.

“Gratitude is talked about on a regular basis here,” Crabb says. “It comes up a lot in our morning meeting.”

Moving from the streets to a shared space can be overwhelming for many at first. To this end there are several small, quiet rooms for people to be alone in. She adds that, although some people are simply loners, the majority of residents bond with one another through communal meals and activities. The MAC has even sparked romance, and new couples have found housing together off-site. (Condoms, available in baskets in all of the bathrooms, go quickly, Crabb says.)

- Linda Stansberry

- Safe sex is encouraged at the MAC.

- Linda Stansberry

- The back garden area.

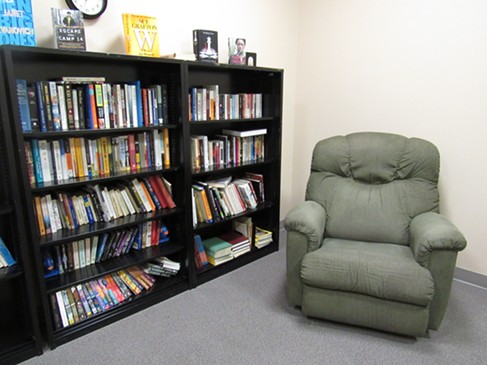

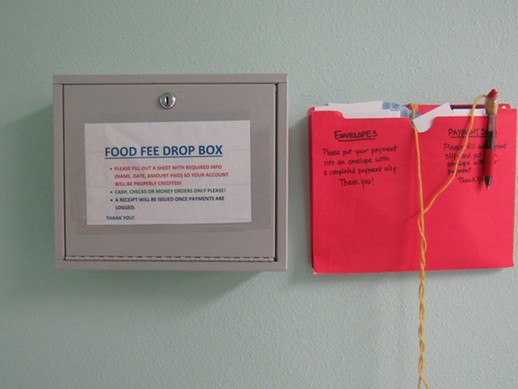

Most clients have some form of income, whether it’s Social Security, General Relief or CalFresh (formerly known as “food stamps”). Clients are expected to contribute to the food fee on a sliding scale using a donation box on the wall, and Crabb says that many conspicuously add their contribution – it’s a point of pride. Residents are also responsible for daily chores that help keep the facility clean. Cleaning the small library is a popular task.

- Linda Stansberry

- The facility's well-loved library.

The ultimate goal of the MAC is to get clients into housing. MAC staff do not do this themselves, but rather coordinate with caseworkers and other local resources. The MAC keeps clients supported while they try to find housing, with an aspirational turnaround of 30 days. In reality, most clients transition out between 30 and 90 days. The majority go into permanent housing, according to Crabb, although some go into transitional housing (such as clean and sober houses). The only behavior that merits ejection are violence, threats, unmanageable substance abuse or “extreme” contraband such as weapons. Some clients leave of their own accord, but are eligible for re-entry after 30 days. “Wilingness and a want to be housed” are the most important criteria, according to Crabb. Although they often get calls from family members or caregivers hoping to house people, the client’s willingness is the deciding factor. So far 65 people have been successfully housed and 51 have left, either of their own accord or after expulsion.

- MAC

- Client's love contributing to their meals, says Crabb.

Every Friday MAC staff meet with county representatives to discuss what is and isn’t working; around the time the program turns a year old they will discuss any changes that need to be made. Some tweaks have already been implemented, including an expanded direct referral service. Others, such as a dedicated program to improve success rates for youth age 18-21, are in the works. This age group, Crabb says, struggles to bond with the older adults in the program and also have less in the way of life skills. The “peer milieu” is very important, she says. Announcements of small successes are often met with cheering and clapping by other residents.

Crabb says that success is defined by the residents and their individual goals. A small change, such as a minor surgery that relieves chronic pain, can radically change a resident’s chance of success.

“We look at people holistically. We listen to their goals, we follow their lead,” she says. “Everybody has their own dance to do.”

As she explains this, a tall, older man waves at Crabb from the lobby. She waves back and he gestures enthusiastically towards his head, which is topped with short grey hair.

“Nice new ’do!” shouts Crabb, and the man comes shyly up to the window of the office.

“I knew you’d want to see the haircut,” he says, before nodding politely and walking away.

“You wouldn’t have recognized him before,” Crabb says once he’s gone, explaining that when he arrived his hair was long, unkempt and curly. As she speaks, other people are beginning to filter in, rubbing their hands experimentally over their newly shorn locks. It’s Friday, haircut day, and the MAC clients are excited.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1