In December of last year, residents of the Aiy-yu-kwee Mobile Home Park — located on the territory of the Blue Lake Rancheria — were expecting to receive the usual season's greetings: good tidings and Christmas cheer. Instead, they got eviction notices.

When 76-year-old Sid Madjarac received his letter, the first thing he thought about was his age and how big a pain it would be to move. But Madjarac, a Korean-war vet, is a fighter. And as it turned out, his eviction came with a silver lining.

Someone from the rancheria called him just before Christmas and invited him into the tribal offices for a chat. When he went in, Tribal Administrator Arla Ramsey told him she had good and bad news. Madjarac already knew the bad news — he had to leave. The good news was that the rancheria would arrange to rent him a new trailer for the same price he was paying at the mobile home park.

Madjarac, a frequent patron of the Blue Lake Casino, was delighted. "Wow, this is pretty good," he thought to himself. He even wrote Ramsey a thank-you card. But then he learned that many of the park's residents hadn't been offered the same deal. Now he's irate, and he refuses to accept what he considers to be the tribe's inequitable offer.

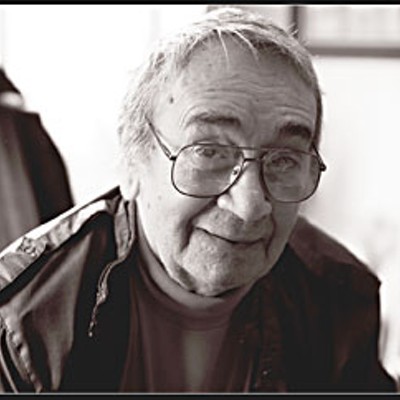

Madjarac is the sort of guy who would blend in perfectly at a card table in Atlantic City in the 1970s. At a meeting held by the Aiy-yu-kwee Mobile Home Park residents on a rainy Sunday afternoon in January, the salt-and-pepper haired war veteran wore aviator glasses and a bright red turtleneck under a brown windbreaker jacket. In a voice made gravely by smoking, he explained how he'd decided to reject the tribe's offer of alternative housing: "I woke up," he said. "Hey man, that's not Madjarac ... I'm going to go down with the other people."

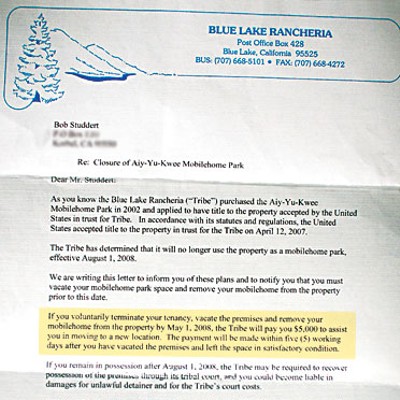

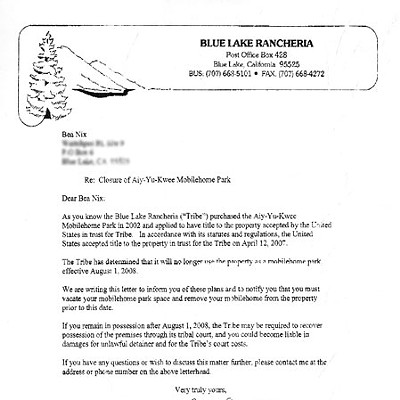

The eviction notices, which the Blue Lake Rancheria Tribe sent to all 18 units of the mobile home park at the beginning of December, were similar in spirit, but differed in their details. Residents have until Aug. 1, 2008, to vacate the property and clean up their lots, or else face litigation. But some residents were offered $5,000 if they agreed to voluntarily terminate their tenancy and vacate the premises by May 1. Others, like Madjarac, were promised housing elsewhere on the rancheria. And an unlucky few were sent packing empty-handed.

The state of California protects mobile home owners' rights, but the Aiy-yu-kwee Mobile Home Park (aiy-yu-kwee means hello in Yurok) is on tribal land, and has been since April 2007, when the property entered into tribal trust. Because of the tribe's sovereign nation status — like that of all Native American tribes in the United States — it's not subject to state laws. Even though Aiy-yu-kwee residents work in California and vote in the state's elections, they go to bed in a sovereign nation. That means it's perfectly legal for the tribe to come up with its own conditions for evicting mobile home park residents.

Whether or not the tribe's actions are fair is another matter. Many of the affected residents wonder how a tribe that promotes itself as a positive force in the community and a protector of the disenfranchised — according to the rancheria's website, its business goal is "to serve those who remain underserved by the system" — is kicking them out. For the tribe's part, they feel they are acting in the best interest of their members by redeveloping a park that loses money into something that will turn a profit.

Still, the residents have questions about how the tribe has acted so far. They want to know what criteria the tribe used to determine who will and will not receive remuneration for leaving the park by May 1, and whether or not the decision was voted on by the Blue Lake Rancheria Business Council, which is made up of the tribe's five elected officials. Residents also question how fair it is that they are significantly less protected than they would be if the park were located just a stone's throw away in the city of Blue Lake, where California's Mobilehome Residency Law provides a safety net for mobile home owners in just this sort of situation. Moreover, relocation costs, which can run as high as $13,500 for a doublewide mobile home, are prohibitively expensive for many of the residents. And applying for subsidized low-income housing — for those of whom it's even an option — is out of the question due to time constraints. (According to the Humboldt Housing Authority, the process for acquiring Section 8 low-income housing can take three to four years to complete.)

As the weeks have passed since the park's residents first received their eviction notices, the tribe has tried to patch the situation. They have offered one-on-one meetings with the residents and just recently provided them with a list of possible housing alternatives. At the last Blue Lake City Council meeting, a member of the rancheria's business council — not there in an official capacity — offered to arrange a meeting between the council and the residents. Such gestures on the part of the tribe, which still fail to provide the mobile home park residents with the same minimum protections guaranteed to Californians under the Mobilehome Residency Law, seem to reinforce the usefulness of having such a law, or at least following it.

"We're too old for this,"Sarah Helen Studdert said as she rifled through papers in her crowded trailer the first week of January.

Studdert, a short, stout woman with deeply wrinkled skin and long silver hair, was looking through documents and correspondence from the Blue Lake Rancheria, hoping to find something that would help postpone the inevitable.

But there was nothing.

In April of last year, the mobile home park property entered into tribal trust, and in a flash its residents lost the rights guaranteed to them by the state of California under the Mobilehome Residency Law. Studdert and her husband signed an agreement with the tribe allowing them to do that. However, other residents say they were never asked to sign anything. One thing is certain: The Studderts weren't aware of what they were giving up when they signed on the dotted line.

"Everyone had to sign a paper putting the land into Indian trust or they had to move out," she explained, her slight southern drawl betraying her native Oklahoma. The Studderts never received a copy of that document.

Studdert and her husband moved here in 1987, when it was still the Blue Lake Mobile Home Park. Now, the front porch is overgrown with thickly knotted foliage. The inside of their trailer is packed to the gills with two decades full of possessions. There is hardly even a place to sit. The sofas are crowded with boxes and papers. Every inch of the living room walls is covered with photographs. Studdert has 23 grandchildren and their baby portraits are lined up one after the other starting just above the front door.

"I've got my roots here," she said. "I'd like to stay." And it's not just a matter of sentimental attachment — the Studderts say they don't have the money to move their home.

To say the evictioncame as a complete shock to the Studderts and Sid Madjarac, just to name a few of the 30 or so people affected by the tribe's decision, would be unfair. When the rancheria bought the Blue Lake Mobile Home Park in 2002, they told residents that they would develop the property sometime in the future. But according to residents, the tribe wasn't clear about the time frame.

Studdert remembers attending a public hearing in 2006 where the tribe showed residents plans for developing a hotel, a Native American cemetery/village site and an RV park. When Studdert asked how the mobile home park would be affected by the development, Studdert said Tribal Administrator Arley Ramsey "never would give a clear answer."

"They did not tell us in black and white that we were definitely going to have to move," she said. And so the Studderts just assumed they'd be able to live out the rest of their lives on the rancheria.

Arla Ramsey disagrees. "They all knew from the beginning," she told the Journal last week in the rancheria's tribal office. "From the day we bought it [the trailer park], the number one question that they asked was: ‘Are you going to close the park?' And our answer has always been the same: ‘We don't know. We plan on running the park as it is now. There's a possibility that we'll close it in the future.'"

Ramsey doesn't look like a typical administrator: She has sharp features, shortly cropped purple hair, a geometrical tattoo running down her jaw and others on her wrist and finger. She's also vice-chairperson of the tribe's business council and CEO of the Blue Lake Casino.

"They have month-to-month contracts with us," Ramsey explained of the residents. "That's another reason why we didn't give leases because we didn't know what was going to happen. Leases are a guarantee ... by giving a lease you're making a promise that you may or may not be able to keep."

Still, the Studderts weren't alone in thinking that the park wouldn't be developed anytime soon.

Cory and Susie Holderman purchased a mobile home for $120,000 in the park about three and a half years ago and still have upwards of $60,000 left in mortgage payments. Holderman estimates it will cost about $13,500 to move their doublewide trailer off the property — that is, if the Holdermans can find some place to move it to. Empty mobile home lots are few and far between in Humboldt County, and the handful of parks with available spaces don't accept trailers over 10 years old.

At the entrance to the Aiy-yu-kwee Mobile Home Park is a sign telling prospective buyers to speak to a representative of the rancheria before purchasing a trailer there. Holderman says he talked to Ramsey before making the decision to buy. Though she made no specific promises that the trailer park would not be developed in the near future, he said, she did imply that much.

According to Holderman, Ramsey told him that if the park were going to change use it would involve the federal government and it would take years for things to be worked out.

"The rancheria management said that there were no plans and they said they [the park's residents] didn't need to worry," Holderman said. "If they said we planned to do something in the next couple of years, I wouldn't have bought this place."

However, Ramsey insists that some prospective buyers, afraid of the risk, decided to purchase elsewhere.

Holderman is a youngish-looking, round-faced, mustachioed father of two who runs his own computer repair business. He says that moving their home could ruin them financially. When he talks about the evictions, his voice quavers with a mixture of nervousness and anger.

"I feel like this is a mafia-style action," Holderman said when reached at his home the first week of the New Year.

"I believe that's it extremely unfair," he said. "The standard practice in the state of California is that when a business decides to close down a mobile home park, the residents are basically bought out."

"You can sure feel for the people," said Blue Lake City Manager Wiley Buck, reached later at his office.

Which is just about all the city can do. Blue Lake's tribal liaison, Marlene Smith, has spoken with the tribe on behalf of the mobile home park residents, but the long and the short of it is that the city has no authority over how the rancheria manages trust land.

Joseph Kalt, Co-Director of the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, explained the sovereign nation status of tribes from his office in Phoenix, Ariz. "You and I think of them as being in California," he said. "No, they're not. They're actually just surrounded by California. They're just a neighbor of California."

That's why Ron Javor, assistant deputy director for the California State Department of Housing, said that when it comes to mobile home owners' rights on tribal land, "everything kind of goes out the window." Mobile home owners in California have "very extensive protections," he said, but tribes are sovereign nations.

Javor said he'd never heard of a case quite like this one before.

If the Aiy-yu-kwee Mobile Home Park were in Blue Lake, then the residents would have at least one year to move, Javor explained. Moreover, the owner of the property would have to prepare an environmental impact report, stating what the intended future use of the property was, then get local government's approval before moving ahead with its project. They would also have to identify new housing for the park's residents and calculate relocation costs, which, in all likelihood, they would have to cover out of their own pocket.

In short, the Mobilehome Residency Law is designed as a deterrent, to be expensive for property owners who want to change the use of a park. The rancheria can't be expected to follow it word-for-word since their property is governed by federal laws, but if they had voluntarily followed key elements of the law — those providing for adequate heads-up, public hearings and help in identifying alternative housing early on — they probably could have saved themselves a lot of headache.

Ramsey said that she was aware of the law but that it never came up in conversation with the tribe's lawyer when he was drafting the eviction notices.

This isn't the first time that the Blue Lake Rancheria Tribe has been criticized for sidestepping California state law. In 2003, the Journal reported on the business practices of Mainstay Business Solutions, a staffing company and tribal entity of the Blue Lake Rancheria that was operating outside of California's workers compensation laws.

As a business entity of a sovereign nation, Mainstay Business Solutions was able, for a time, to avoid California's workers' comp premiums, which are some of the highest in the nation. But as soon as state regulators realized what was going on, they tried to put a stop to it. As a result of the state's complaints, Mainstay was forced to buy traditional workers' comp coverage from an insurance provider in the state of Washington, which caused their revenue to plummet from $300 million to $120 million, according to a report in Business Insurance.

In late 2003, Mainstay sued the Department of Insurance and the Department of Industrial Relations in order to get them to stop interfering with its operations. Mainstay and the Department of Industrial Relations finally settled out of court in 2005, with Mainstay agreeing to pay a $20 million deposit — mostly in cash, according to a report in the Sacramento Business Journal —to self-insure, as well as wave its rights to sovereign immunity. (As for the Department of Insurance, Mainstay dropped its suit against them.)

In a much less flashy arena — a mobile home park, where monthly rents are a mere pittance compared to the sort of cash that fills Mainstay's coffers — and much closer to home, the tribe's sovereign status is under scrutiny again. And again it seems — at least in the minds of the park's residents — that complying with California state laws protecting mobile home owners could have saved the tribe an unnecessary headache.

Bea Nix, who owns a second home in the trailer park, is less than copasetic about her eviction. Nix, a member of the Yurok Tribe, lives in Weitchpec. She feels that the tribe's sovereignty is being misused when it strips people of their rights, especially when the state of California gives mobile home residents significantly more protection than the rancheria does.

"I want to know why they aren't respecting that standard [the state's]," she said in a phone interview. "Do they think we are substandard people? Do you have a right to treat me as a native person less than the dominant society treats its community members?"

Nix is full of vituperations. "They're giving Indian people a bad name," she said of the rancheria. "To me this is like an old novel where a landlord baron is treating people in any manner they want and getting away with it because of their power."

At a recent meeting of the mobile home park residents, Nix, a tall and striking middle-aged woman with long, curly black hair, abalone shell earrings and a heavy, beaded necklace slung around her neck, spoke out resolutely against the injustice that she says has occurred. And when she wondered aloud why she and her husband had not been offered $5,000 if they moved out by May 1, other residents let out a gasp. Up until then, they'd just assumed that everyone had received the same letter.

It's hard for park residents to believe that a body of elected officials voted to evict them.

When a reporter called the chairperson of the Blue Lake Rancheria Business Council during the first week of the New Year to inquire about who made the decision to evict the mobile home park residents, Claudia Brundin didn't sound happy. So she put Diane Holliday, also a councilwoman, on the line.

Was it the business council who gave the green light to evict the residents? There was a slight pause.

"I don't remember whether we took an official vote or not," Holliday said. But she was sure of one thing. The council definitely discussed it and they all agreed that evicting the residents was necessary.

Luckily, Arla Ramsey's powers of recall are better. She told the Journalthat in September 2007 the business council voted unanimously in favor of evicting the mobile home park residents. After that decision was made, the tribe's lawyer began drafting the eviction notices and finished in time for them to be sent out just before Christmas. Although many of the residents have complained about the timing of the letters, Ramsey insisted that they were sent before the holidays so that residents would know not to overspend on holiday gifts.

As for why the council decided to redevelop the park, the bottom line, according to Ramsey, is that in its present state, the property is a bad investment. "When we purchased the park, the infrastructure ... was shot," she said. Due to its defunct septic system the tribe has had to make repairs more often than their pocket book can bear.

"We looked at tearing it all out and then putting new in and moving a whole lot more mobile homes in but it's just the people down there right now wouldn't be able to afford to stay there," Ramsey explained.

She said the rancheria plans to build an RV park or storage units on the property, which will the give the tribe a much better return on their investment. Construction could begin as soon as next summer, she said.

Ramsey readily admits that the circumstances are "unfortunate" for the residents. But the tribe is limited in what it can do to help. After all, it has its own members to think about, and as it is, they're not receiving per capita payments from the tribe. She said that the payments the tribe has promised the trailer park tenants are already hard enough to explain to the rancheria's members.

"We're giving out this many thousands of dollars," she said, "to people in the trailer park who are tenants who knew this thing was coming, but weren't positive and decided to take the chance of staying there .... That tribal person will say, ‘I don't care about them. Give me the money.'"

That's why Ramsey hopes that with all of the recent press about the evictions, the community will reach out to those families in need.

"The tribe has made a decision and they're going to close the park," she said. "And there's a lot of families here that are going to be devastated by it. As a community, why don't we get together and try to help them? I can't believe that in Humboldt County there's not one or two places out there that somebody has that they're interested in allowing someone to live on."

And Holliday is optimistic. "We are trying to work on solutions," she said. "It's not like we're throwing people to the lions. I wouldn't be caught dead on a council that would do something like that."

On Tuesday, Jan. 8, a bevy of park residents sat in Blue Lake City Hall waiting anxiously for the trailer park issue to come up on the agenda. At that meeting, Marlene Smith, Blue Lake's liaison to the tribe, said she had spoken with Arla Ramsey the week before and that the tribe had provided her with a list of available mobile home spaces for the park's residents. But residents tried to explain to Smith that they had already spent the past month scouring the county and what they'd found out was that their trailers are either too old for the available spaces, or too wide.

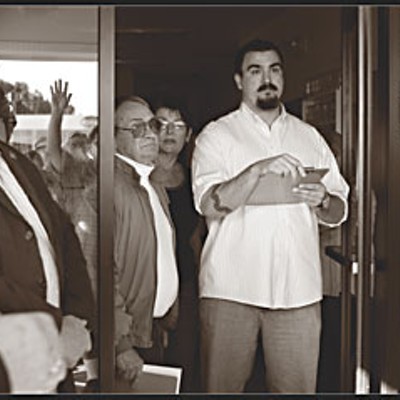

Diane Holliday sat in the front row, an empty seat separating her from the rest of the crowd. Holliday told the council and the residents that she had come as a private citizen, not as a representative of the tribe. Nonetheless, she soon became the lightning rod for everyone's mistrust and angst.

We've been calling the tribe for five weeks and haven't gotten a meeting, one woman said. They're giving us the shine job, a man shouted. Holliday was visibly upset by the reception she was getting.

"We're not trying to be disrespectful," said a soft-spoken Susie Holderman. "We just want them [the tribe] to play fair."

Resident Bonnie Sue George tried to explain how difficult the move is going to be on her and her husband Michael. "People seem to think these are little boxes that can be picked up and moved," she said. "But we're moving our entire lives and our dreams in one blow."

In a letter George gave to the city council, she wrote, "Don't ever think you can't become homeless when you have worked all your life with plans of saving money, just to pay medicines, pay off your home, to keep a roof over your head."

In the end, Holliday promised to arrange a meeting between the tribal business council and the park's residents — the first yet. She did this, she said, "so you [the residents] can have a perceived bigger voice."

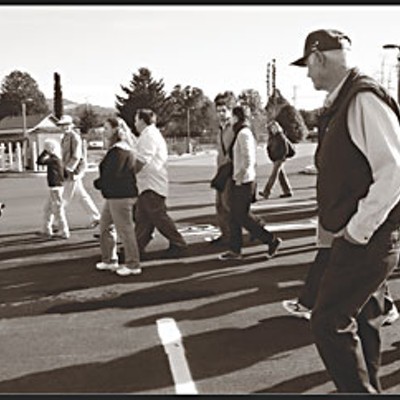

A crowd of almost 40 people gathered peacefully in front of the Blue Lake Rancheria's tribal office on Sunday, Jan. 13, hoping to be allowed into the first meeting ever between the mobile home park residents as a group and the tribe's business council, which had voted last September to evict them. In attendance were residents, their children and grandchildren, Blue Lake community members (including a large delegation of students from Dell'Arte) and two members of the Blue Lake Rancheria tribe, who came to show their support for the residents.

At the entrance to the tribal office stood three security guards; at least one of them, according to his ID tag, was an employee of the Blue Lake Casino. The tribe announced that only park residents would be allowed into the meeting, and that videotaping was prohibited. Even close family members were not able to go in. Resident Bonnie Sue George wanted her daughter to accompany her, and Helen Studdert wanted her daughter and granddaughter to come in, but all three were told to remain outside. Two Blue Lake Rancheria tribal members, Helen Lance and her son Joe, were also denied entrance to the building.

Just an hour earlier when the mobile home park residents had met to discuss how they planned to bargain with the business council at that afternoon's meeting, the group resonated with a tangible sense of purpose and hope. Their faces were bright and smiling and everyone had donned their Sunday best. They had been waiting a long time to face the tribe together and thought they might actually get the chance to hammer out a more equitable solution to their problems. They had planned to introduce themselves one by one to the business council, with a member of the Blue Lake community standing beside each resident for moral support. They hoped that if the tribal council members heard their individual stories, they might reconsider their decision. But standing in front of the tribal office and being told that neither Blue Lake community members nor the press could attend the meeting took the wind out of their sails. For a moment they considered backing out. If it wasn't going to happen on their terms, maybe it shouldn't happen at all, some argued. But in the end, they decided to go in alone — even if fewer voices would be heard, that was better than nothing, they reasoned.

Waiting outside for her mother on a park bench, Helen Studdert's daughter Nancy Buzzard was upset that she hadn't been allowed in. "I can't believe this is happening," she said about the evictions. "They're going to be basically homeless."

Joe Lance was just a few steps away talking to a group of Dell'Arte students. "As a community member, you'd think I'd be able to go into the community center," he said. Lance and his mother feel that the tribe has gone downhill since the death of Helen Lance's sister, Sylvia Daniels, who was instrumental in getting the Blue Lake Rancheria federal recognition. Helen Lance believes that the evictions are not supported by a broad base of the tribe's members: "It's the business council, it's not the tribal members," she said.

And then, just like that, the meeting was over. It hadn't lasted more than 15 minutes.

"Nothing's going to change," a red-faced Sid Madjarac said when he stormed out of the building. "We got kicked to the curb," someone else said. "We asked, they're not answering," said another. Then Bea Nix announced: "We need to go to plan B."

As Rick Horton wheeled his wife Frances Tharp out of the office in a wheelchair, the couple was finishing up a conversation with Diane Holliday they had begun inside. "We can at least be lady-like," Tharp said to Holliday. "What do you know about being lady-like?" Holliday snapped. Tension was obviously running high.

Marlene Smith, Blue Lake's liaison to the tribe, sat in on the meeting, and she sounded as pessimistic as the others. Standing in a throng of residents who were explaining to their families and concerned community members what had gone on inside, Smith described the meeting as "frustrating, because neither side was able to meet with any understanding." She said that a solution would have to come from the community. The City of Blue Lake has no money to spare on legal aid for the residents, she said.

As for the tribe's stance, it hadn't changed. The meeting was definitive proof that they had drawn a line in the sand.

The residents, their families and members of the community regrouped in the mobile home park at Bonnie Sue and Michael George's house. Their doublewide has a huge, multi-level deck. The cozy living room, with wall-to-wall carpeting, has overstuffed couches and paintings of flying eagles on the walls. And the towering cupboards that separate it from the kitchen are covered in a jungle of fake plants and flowers. Their home may have no foundation, but moving it won't be easy. And in this quaint mobile home park where half of the houses are ringed with white picket fences, the George's home is no exception to the rule.

Gathered in the George's living room the residents tried to muster their forces back. This time, unlike just hours before, hope had been replaced by anger, but most seemed ready for the fight ahead. Some insisted that they pool their resources together and hire a lawyer. Others said it was too early. They needed to form an association first, pool funds, start a website, launch a letter-writing campaign and begin reaching out to the community, starting with local churches.

As for their association's name, it would have to be simple. One thing was for sure: They didn't want to be known as the Aiy-yu-kwee Mobile Home Park Association; that reminded them of the tribe that had gotten them into this mess in the first place. They would call themselves the Blue Lake Mobile Home Park Association because in the park's former incarnation, at least the residents had rights. They had never gathered en masse to discuss those rights. In fact, until they received their eviction notices, some of the residents of this tiny mobile home community weren't even on a first-name basis.

But now, with their rights in limbo, the residents are looking to one another for strength and support, and they are finding that even though their homes may have to be dismantled and moved in the not-too-distant future, a steadfast sense of resolve has built up among them.

Comments