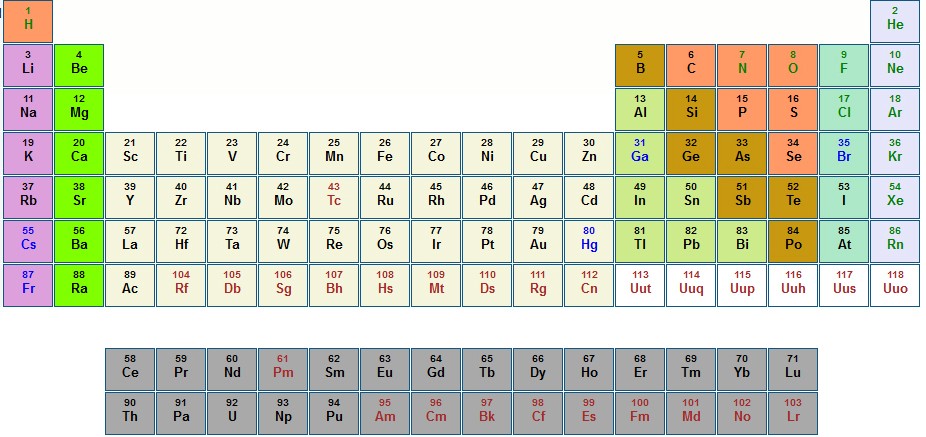

- First conceptualized by John Dalton (1803) and formalized by Dmitri Mendeleev (1869), the periodic table shows the 118 known chemical elements, grouped in vertical columns according to their properties.

The story of how science came to understand what we're made of really began with "the Father of Chemistry," French nobleman Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. Before he lost his head to the guillotine during the French Revolution, Lavoisier recognized that stuff came in two varieties: that which could be broken down into simpler stuff (compounds) and that which couldn't (elements, as in elementary). This simple-yet-momentous observation prepared the groundwork for the science of chemistry.

Ten years later, in 1803, English scientist John Dalton quantified Lavoisier's insight. Reviving the ancient Greek term for indivisible atoms (a-tom, that which can't be cut), Dalton's genius was to suggest that what distinguishes the properties of one element from another depends on the mass of each of its constituent atoms; and that compounds are formed by a combination of elements in simple whole-number ratios (e.g. two atoms of hydrogen combine with one atom of oxygen to make water).

We now know that (1) an atom is composed of light, negatively charged electrons surrounding a heavy, dense nucleus consisting of positively charged protons and neutral neutrinos; and (2) one element is principally distinguished from another by the number of protons in its nucleus.

Recall the Periodic Table on the wall of your school science lab? Dalton's successor, Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, invented this ingenious way of arranging elements according to weight (left to right) and properties (top to bottom). So for instance: The lightest element, hydrogen, atomic number 1 (whose nucleus contains just one proton) is upper left; organic compounds all contain carbon, atomic number 6 (six protons in each nucleus); uranium, atomic number 92, is the heaviest naturally occurring element.

The beauty of the periodic table is its universality: Everything (everything!) you touch, see, smell and taste consists of either pure elements or, more likely, a mixture of the elements found in this deceptively simple matrix. Take your body. It's made up of about 65 percent oxygen, 18 percent carbon, 10 percent hydrogen and 3 percent nitrogen by mass, while the remaining 4 percent consists of traces of almost every other naturally occurring element in the table.

Since the time of Lavoisier, Dalton and Mendeleev, chemists, physicists and astronomers have made huge strides in understanding the origin of elements. Thirteen-plus billion years ago, soon after the creation event we term the Big Bang, the universe consisted only of the lightest elements hydrogen, helium and lithium (one, two and three protons, respectively). No carbon, no oxygen, no zinc, no iron, no uranium: These had to be synthesized from the original three elements. How? By nuclear fusion. Where? Inside stars. So many technical problems had to be solved in order to arrive at a complete understanding, that detailed answers have only been available in the last 50 years. And the biggest hurdle investigators had to overcome is right here in your blood: iron.

Next week: Forging the elements.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) recommends Tom Lehrer's The Elements for anyone wanting a quick brush-up. Son of Field Notes (a compilation of Barry's columns for the last 18 months) is for sale at Eureka Books and Northtown Books.

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4