IT ALL STARTED WITH A DOG.

Lincoln Kilian says he originally unearthed the story of Boomer Jack sorting through clippings in his job as an HSU librarian, a job he'd had since 1966. In 1977, he was transferred to the Humboldt Room, which houses the library's special historical collections. Part of his assignment in the Humboldt Room at the library was to maintain the pamphlet files. In those files he found an undated story from a defunct local paper about a stray dog that rode railroad trains. He showed it to his then-boss, Erich Schimps, who at the time thought it would make a nice children's book.

Kilian was intrigued. He was drawn into a search for the true story of this mysterious dog, tracking down one of the old-timers quoted in the story, Reggie St. Louis, who was ailing but still alive, in his late 70s. St. Louis also gave Kilian the names of several other locals who might know more about the legendary hobo dog, who was called Boomer Jack, or Hobo Jack, or Bummer Jack.

Kilian's obsession with the story was cemented when a train conductor's widow produced a photo of Boomer Jack's funeral, a picture where none of the men were identified. It then became in Kilian's own words, "an intense personal mission" to discover the true story. For months he tracked down old railroad workers throughout Northern California, many in their 80s and 90s, eliciting memories of the peripatetic hound and his travels.

The more he learned, the more he had the feeling that he had uncovered what he called "an all-but-forgotten folk hero."

Eventually he made his way down to Willits, which was the central stop on Boomer Jack's run. Thanks to the tip from a local newspaper staff, he found a former Northwest Pacific Railroad man named Bob Brown who remembered Boomer Jack. Brown drove Kilian to the rail yard and pointed out the locale of Jack's resting place, a landscape which precisely matched the line of hills in the funeral photo. After completing this last part of the puzzle, Kilian finished his book, and the Mendocino County Museum published A Dog's Life: the Story of Boomer Jack in 1998. Right before publication, Kilian acquired an agent to sell the movie rights thanks to the intercession of his ex-wife. He was elated. His book eventually went through several printings, first selling at the museum bookstore, but eventually landing in other outlets through Kilian's persistence.

Earlier this year, a different telling of Boomer Jack's story appeared -- this one a story for children. Writer Tim Martin's fictionalized The Legend of Boomer Jack shares several historical incidents with Kilian's historical booklet, and the private fight over who has the right to tell the dog's story that's been building for some time has finally gone public.

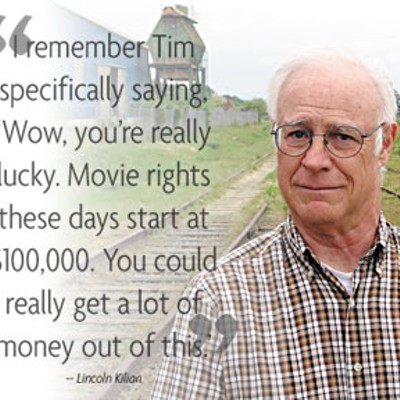

Both Kilian and Tim Martin agree that the rift between them was sparked when they met while doing something they both love -- running. (Tim Martin's earlier books, and a regular newspaper column in the Times-Standard, are about that subject.) In 1997, Kilian ran into Martin at the annual Patrick's Point Run. Kilian says he knew Martin was also a fellow writer, and had a friendly acquaintance with him, so he excitedly shared the news of the publication of his upcoming historical booklet. He says he told Martin of how he "spent a couple of years working on the story of this railroad dog I discovered. I told him about all the work I did, running around tracking down sources." Remembering that he'd read that Martin was working on a screenplay, he also mentioned that he himself had acquired an agent for a possible movie sale. "I remember Tim specifically saying, `Wow, you're really lucky. Movie rights these days start at $100,000. You could really get a lot of money out of this.'"

Less than a year after his meeting at the Patrick's Point Run, Kilian says he was walking through the library from which he'd recently retired and was told by a reference librarian that he'd just missed Tim Martin by a few minutes. Kilian was told that Martin was looking for information about railroad dogs for a screenplay he was writing. Kilian was crestfallen. "There's only one way he could have found those articles on Boomer Jack: by checking the local papers under a couple of dates mentioned in my story," he says. "Dates it took me hundreds of hours to locate. I know he found nothing in any index, database or other reference source. I checked them all myself."

That moment in the library marked the beginning of a decade-long conflict between the two men over who had the right to tell Boomer Jack's story.The story is further complicated by the possibility of Hollywood money.For Martin, Boomer Jack is a means to an end -- a story that might be his entrée to an industry notoriously tough to break into. Kilian is also interested in a possible film, but he feels his main role is the guardian of the true historical story of Boomer Jack, a story that he's fiercely protective of.

"Tim was writing a screenplay based on Boomer Jack," Kilian says, remembering that day in the Humboldt Room. "He had seen my book. I thought he was stealing my own story, and I was so mad."

Boomer Jack wasan independent black bob-tailed dog of uncertain ancestry and no fixed address who appeared in the 1910s, adapting the Northwestern Pacific railroad as his home line. He rode the rails between Trinidad and the San Francisco Bay, and at one point rode cross-country and back. Over the span of 14 years, he was seen everywhere from Blue Lake to Marin. He rode the Eureka streetcars, and he mooched for food on the streets of Arcata. In fact, it was said that he knew the routes of the streetcars in Eureka, and could locate particular railroad men's houses despite the fact they were located far from the train station.

What set Boomer Jack apart was his sense of independence and freedom, characteristics that the men of the Northwestern Pacific who fed and cared for him admired. Jack, unlike other railroad dogs of legend, belonged to no one man. He would ride the rails to a particular town, stay for a day or two and be on his way, never overstaying his welcome. He would even, on occasion, ride passenger trains. He ranged far and wide, even staying in a San Francisco hotel after being smuggled in by one of his railroad buddies. Eventually he was discovered and kicked out, but returned to the establishment later to lift his leg and leave his mark.

At one point Jack vanished, his whereabouts unknown. Some thought he had disappeared forever. Then the Northwestern Pacific home office received a telegram from some trainmen located in South Carolina, asking about a dog with a NWP badge on his collar. Boomer Jack had somehow made a cross-country train journey. Relieved that their mascot was still among the living, they wired instructions for his safe return to the West Coast. He was watched over by linemen along the way, and was returned safely back to his home line.

His tenacious instinct for travel continued even after he suffered a severe leg injury from a train fall. His accident elicited sympathy from up and down the line, and a fund was established to pay his medical bills. So much was raised that a bank account was opened up in his name in Eureka. His lame leg slowed him quite a bit, and as he aged he often needed help getting up into a cab. In 1926 in front of the Willits station, Jack was found lying peacefully on the ground by Bob Brown and his fellow workers. A small redwood coffin was fashioned, and he was buried in the switchyard. Boomer Jack was gone.

It would be an understatementto say Lincoln Kilian has a strong attachment to Boomer Jack and his story. When you hear him speak of Jack it's as though someone has stolen his own dog.

"I thought he [Martin] was writing a screenplay about the real Boomer Jack," Kilian says. "I think I had a right to be pretty angry. Although I must say he was honest about it, when I finally caught up with him he was totally unflappable. I said, Tim, don't you realize I've spent years on this? This has been my labor of love.' He was unfazed and said,That's what it's been for me, too -- a labor of love.' I could hardly believe it.

"When I came away from the conversation it was like no other human interaction I'd ever had before. Then I thought, he's trying to break into movies, it's really hard. The chance you'll pull it off, it's just not worth worrying about."

Lincoln Kilian is adamant that Martin based his fictionalized story on his own laborious hours of research, and Martin would never even have known of Boomer Jack if not for the publication of his own book. "It's not the sinking of the Titanic or the Civil War," he says, "it's one subject, one book, by one person -- there's nothing else published on it. I put my heart and soul into this, I spent thousands of dollars traveling. I bought microfilms of periodicals, tracked down railroad magazines for $100 a copy."

The story took another turn in 1999, when this paper published a profile of Tim Martin, in which he claimed that his Boomer Jack screenplay had attracted the interest of HBO. According to Kilian, he phoned the story editor at HBO and got a denial that they were interested in the script. The actual letter to the Journal states that Martin had called her for advice, and that was all.

Kilian says his concern is not monetary (a portion of the proceeds of any possible movie sale would go to the Mendocino Museum). At the same time he realizes that the story is a natural for the big screen. He says he has no desire to prevent the sale of Martin's book, but he worries that a sentimentalized, fictionalized version of the story of Boomer Jack will kill any possible interest in a more authentic cinematic version.

"Sentimental dog stories, both true and fictional, are an established genre, like romance novels or murder mysteries," Kilian says. "They focus almost exclusively on the devotion or heroics of a loving, faithful companion. What drew me to Boomer Jack is that he was not such a dog: He was a one-of-a-kind rugged individualist, who never fawned over anyone."

Kilian feels that Martin has taken the unique and quirky story of Boomer Jack, one he's invested a good deal of time and effort in uncovering, and made it into a stock cliché. He also wonders why Martin used the name Boomer Jack if he was going to fictionalize the story anyway -- he feels the actual story is fascinating enough on its own.

"Using the name Boomer Jack would dash our hopes for an authentic film," he says.

Tim Martin sayshe's the kind of writer who has several projects brewing at once, and is always looking for new material. Before embarking on the cinematic version of Boomer Jack, he'd already written several unproduced screenplays. One is called Damn Hippies, a story inspired by a local microbrewery (and with a lead character based on former Arcata mayor Bob Ornelas). Then there's Scout's Oaf, a Boy Scout comedy, and Punk Rock Heroes, the story of a band with the not very punk rock name of Mad as Heck.

Martin agrees that he first heard about the story of Boomer Jack and Kilian's upcoming book at the race, but he has a different memory of the conversation.

"I'm an ambitious writer and I've always got 10 things going," he says. "I asked Lincoln, Have you ever thought about writing a screenplay about this?' He says,Oh no, why would I want to do that? I'm going to let someone else write the screenplay and I'll get rich.'

"I was offended by that as a writer, because I knew what it was going to take to write a screenplay because I'd already written one. It takes about a year to write one of those things, and for somebody to say that to me -- `I'll work off your back, off your labors' -- that's what was really insulting. Up to this point this guy had been a friend of mine. A running friend.

"I didn't think much about it at the time, then I went home and I was thinking it's such a great story, it would make such a wonderful movie. So I thought about it for a few weeks and decided, `I'm going to write my own version.'"

Martin claims that he didn't have to do much research for his screenplay.

"Lincoln's beef is, he says he did all the research -- there's not a lot of research in there," he says. "Well, I just took a few incidents like the Cain Rock golden spike ceremony -- when they tied the rails together -- that was it. The rest is all fiction."

When asked about Kilian's possible claims to the story, Martin takes another tack: "This is history. It isn't characters that you've made up. You're talking to me about something that's really happened. When Steven Spielberg made a movie called Amistad based on the historical story of a slave ship rebellion, the person that wrote a book on the subject tried to sue. He ended up writing his own version of that -- that's history. It's like the story of the Titanic."

Left: Tim Martin and his dog, Boomer. Photo by Bob Doran.

The film is now listed on the Internet Movie Database as being in pre-production. "We have a producer -- he's pushing it around Hollywood," Martin says. "We almost had a sale, then there were some money problems. We have another writer who's looking to do a re-write. I've put it through 20 drafts, so it's real hard for me to make any big changes. Sometimes you need another writer to come on board to do a final draft."

When asked about why he turned his screenplay into a children's book, Martin says the idea came to him when perusing Carl Hiassen's children's book, Hoot, which was soon to be a motion picture.

"I usually work on five or 10 things at once -- many screenplays," he says. "I hadn't even thought about making this into a book. I got the screenplay done and it sat there. I thought it would be a good way to promote the movie if it ever gets made, and it's also a good way to make some extra money. People tend to pick up a book if says soon to be a feature film, it has a little more draw to it."

Tim Martin remains convinced he has as much right to tell Boomer Jack's story as anyone, and feels that it is ironic that Kilian feels he has some special claim on the story.

"This is the story of a real life dog who did not want to be owned," he says. "He did not want to be owned by anyone. And he rode the rails, he was a free dog. One hundred years later, this guy is saying I own that dog."

Recently, Martin,through his lawyer and partner Chris Hamer, sent Kilian a letter accusing Kilian of "libeling and slandering and causing people to refrain from selling or purchasing (Martin's) book or dealing with him or his screenplay" and threatening possible legal action because Kilian had been telling people there was a "legal cloud" over the story.

Martin says he was forced to respond as he did. "As soon as this book came out, Lincoln went to various newspapers and bookstores and put the bug in their ear saying I'd stolen his story," he says. "I could have let it ride, but he started calling Hollywood, he called the producer, he called one of the guys who had done a re-write on the script and said I'm going to sue all of you. The producer called and said, `Tim, you have to get this guy off your back.' I said, There's nothing he can do, we're fine. This is my story.' He said,Well, he could cause a lot of trouble -- people get really skittish about these kind of things down here.'

"I didn't mind it so much here, but that was the straw that broke the camel's back. He tried to make it so I can't get a movie, and that's not going to happen. Nobody's going to get rich off of this. We're going to make a movie and we'll be lucky if it's a feature film -- it's probably going to be a direct-to-video or a television movie."

Kilian claims he never threatened to sue, and that he never spoke to Martin's producer either. If he really was attempting to strong-arm the production, Kilian picked the wrong member of the production team -- he called the writer. "I just called the screenwriter and told him I had written a historical pamphlet on the subject of Boomer Jack," Kilian says. While he admits he used the term "legal cloud," he just meant to say that lawyers were involved in the proceedings.

Kilian has consulted an intellectual property lawyer who told him although historical facts are not subject to protection, he didn't know of a case where a movie or work of fiction was based on one work by one author. The lawyer also said that several years ago he himself registered a title and screenplay treatment that included several of the historical plot points shared by both his and Martin's version of the story with the Screen Writer's Guild.

"I've always doubted our spat need end in litigation," Kilian says. "But if he really wants to sue me, so be it."

The story of Boomer Jack is far from over.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2