Nobody knows for certain who, exactly, was the first to tromp into the swamp-prone land on the north side of Eureka Slough and begin shoveling bay mud into a long, snaking heap. Likely it was a farmer or rancher. It happened some time between 1901, when Frank Herrick bought 268 acres between Eureka and Arcata, and 1931, when a photographer went up in an airplane and took a photo that shows the pile, now about a mile long, bordering a portion of the slough west of Murray Field.

What is known is that the Jacobs Avenue Levee has held up remarkably well through 80-some years of storms and twice-daily tides. It's never been breached. And over the years there's been enough confidence in the levee for development to proliferate on the 45 acres (of Herrick's original 268) that it protects. By 1941, the former tidelands had been converted to agriculture. In 1949, Harold Hilfiker subdivided it. In 1956, it was annexed into the City of Eureka. And by 1963, half of the acreage had been built on.

Today, the area, served by Jacobs Avenue, a Highway 101 frontage road just east of downtown Eureka, is a fully developed, eclectic stretch of commercial and residential properties. Here you can buy tropical fish, animal chow, chew toys, a remodeled stove, parts for your big rig, oxygen, fire extinguishers, a water pump, a roof, a couch, cowboy boots and Christmas ornaments. You can order everything from office furniture to clutches to chemicals for your hospital or sawmill or what-have-you. You can visit your friend at the Lazy J Trailer Ranch -- or just come on home if you've got a trailer there. You can drop your dog off at daycare or the vet or the grooming parlor, or just take him for a walk atop the levee. You can buy a used car, car parts or dump your junker. You can rent a truck or trailer to haul your household goods in. Or, heck, you can stuff all your things into a storage unit. You can attend an auction. And, at the newest business on the block, on the far western end, you can even have your loved one's remains cremated.

But now the Federal Emergency Management Agency is suddenly saying that the properties along this avenue aren't protected from a 100-year flood event -- the level of flood that has a 1 percent annual chance of occurring. Post-Hurricane Katrina, FEMA is decertifying levees all over the country. So, come the end of this year, if the property and business owners can't prove FEMA wrong -- if doing so is too costly -- Jacobs Avenue will be remapped on the federal government's flood risk maps and join Murray Field and other neighbors already in the floodplain.

That will create new restrictions on development on the avenue. And many property owners will have to buy flood insurance; only those without a mortgage from a federally regulated lender would be exempt. But flood insurance doesn't cover inventory, only structures.

And then there's the specter of sea-level rise. And big earthquakes. All around Humboldt Bay, low-lying ground will be at risk of inundation, one way or another. The community might have to make some tough choices -- which lands to fortify, which to let the tides reclaim. Might the folks on Jacobs Avenue be better off just moving to higher ground?

Perish the thought. Moving is not option being considered on Jacobs Avenue. On a recent afternoon in The Farm Store's upstairs lunchroom, the store's owner, Carl "Doc" Johnson Jr., and its manager, Tim Shreeve, spread aerial photos out on the lunch table showing the avenue's development over the years. The most recent aerials were shot by Shreeve, who went up in a small helicopter last October to get a good look at the levee, the slough and all of the businesses.

"I think everybody's pretty much attached to the place," said Johnson.

"We've got too much invested here to think about moving," added Shreeve. He's been with the business for 16 years, and remembers how when he first started they sent him up onto the levee to pull weeds -- a broad, rip-rapped section that Johnson's dad, Carl Sr., built higher and sturdied in the 1970s. To this day it is higher than the rest of the levee.

Johnson's property sits on five acres on the eastern end of the avenue. His dad began the Jacobs Avenue empire 60 years ago on a larger parcel abutting about 800 feet of the levee. He had cattle across the slough, and he ran livestock auctions out of a shack on this side. He added a barn and an equipment repair shop, which today is a veterinarian clinic. He opened Carl Johnson Co. He put in the Lazy J Trailer Ranch about 50 years ago. And 17 years ago he opened The Farm Store. After Carl Sr. died, his two sons split the property: Doc's brother, Don, owns Carl Johnson Co., which is packed with sundry dry goods and furniture and is where, on certain Thursdays, they hold auctions. Doc owns The Farm Store, vet clinic and Pet Pawlor. He used to own the Lazy J but sold it a few years ago. He keeps adding to The Farm Store, though -- most recently, he installed a dark nook where you can sit on a small white couch and watch fish dart in the bank of aquariums covering three walls. And he built a dog-walking trail atop his portion of the levee.

Shreeve and Johnson have been leading the effort to deal with FEMA's threatened map change, with guidance from Hank Seemann, the environmental services manager with the Humboldt County Public Works Department. The county doesn't have jurisdiction over the avenue; the City of Eureka does. But the county's facilities maintenance and heavy equipment yard -- vital in emergencies -- is on Jacobs Avenue. And Seemann has extensive experience dealing with FEMA and other agencies on levee issues elsewhere in the county.

Jacobs Avenue offers good visibility from the highway, ample parking for big rigs and the space to hold big events such as The Farm Store's animal training events and pet fairs.

"To move you'd have to abandon all of what you have here, and hopefully sell the property to somebody else who hopefully could conduct business here," said Johnson. "But if it was in a flood zone it would make it less desirable and less valuable to sell."

"And who do you tell 'You're property's not worth saving'?" asked Shreeve. "How do we tell 150 residents here at the trailer park that, hey, your home's not worth saving. Those are their homes. What's-her-name, down there, she's been there 20, 25 years; she doesn't want to leave."

"And heck, there's 33 businesses here," said Johnson. "Look around the bay: Where would we go? There isn't adequate property round Eureka for us all to move to. So, if we decided that the property had to be abandoned, which isn't even in the thought process, but if we did, all of us wouldn't be able to remain in Eureka. We would wind up in Arcata or McKinleyville. Fortuna. And that would erode the tax base of the city."

Some businesses might leave the county altogether, said Shreeve. Or just quit.

"Some of the owners are old enough to think that way," agreed Johnson. "And this is a significant portion of the city's business district."

"We're not just some outlying farmland," said Shreeve. "We pay taxes and we feel like we want to be here. .. A lot of us have lived here all our lives, and if we start taking these stretches [along the bay] out and start telling business owners, hey, let's just put these back to water ... if we keep pushing businesses away, where are we going to go? Where are our children going to go, and our grandchildren, who grew up here and like it here and want to stay here?"

There's a multi-state effort to determine how much sea level might rise along the Pacific coast in the next century. A national group of flood managers is looking at possibly a 500-year flood standard, said Seemann. In the meantime, in California, the state Natural Resources Agency has issued interim guidelines for agencies to develop adaptation strategies, which say to expect a sea level rise of 16 inches by 2050 and 55 inches by 2100. In addition, the California Coastal Commission won't permit a project around Humboldt Bay if the developer can't prove it can handle a three-foot sea level rise, minimum, right now, and a six-foot-level rise maximum by 2100, says Aldaron Laird, an environmental planner with Trinity Associates, in Arcata.

Several years ago Laird created an atlas of Humboldt Bay for the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District and the state Department of Fish and Game. It documents what the shoreline looked like in 1850 and how it has changed since then. Now he is mapping the current condition of the bay's shoreline, tributaries and sloughs for the California Coastal Conservancy, in an effort to figure out how they might be affected by sea-level changes. The work involves delineating artificial from natural shoreline.

Laird has discovered that about 90 miles of the bay's shoreline is artificial, including dikes. He's also inventorying salt marsh adjacent to the artificial shorelines -- and it's already known that 90 percent of the original salt marsh around the bay was lost to diking and draining. The remaining salt marsh is at risk of further loss if it's inundated by a rising ocean -- in many cases there is nowhere for new marsh to form because of dikes and development. And the drained former salt marsh lands, which have subsided over time from compaction, and other tidelands reclaimed by diking are most vulnerable to inundation.

"I think we're talking about thousands of acres of property that need to have the existing dikes and tide gates maintained or they're going to flood," Laird said.

The trouble with most of Humboldt County's dikes, he said, is that they were built by private landowners. A few -- the Redwood Creek levee in Orick and the levees in Blue Lake and the Loleta bottoms -- were built by the Army Corps of Engineers. Those have their own problems, but the county is responsible for maintaining them. Maintenance of the private levees is up to the individual landowners -- some do a great job, others do nothing.

"So even if they repaired their dike on Jacobs Avenue, for example, and they had a perfect dike, if upriver on Fay Slough somebody is not maintaining their dike and it fails, water comes rushing in and it's going to flow all downhill and it's going to end up behind the Jacobs Avenue dike," Laird said. "You have to look at all of it. All it takes is for one section of dike to break, and it doesn't care about property lines, it's just going to flow downhill. I don't think people think about that very much."

Sea-level rise just increases the likelihood of such failures. And then there's the shifting land itself to consider.

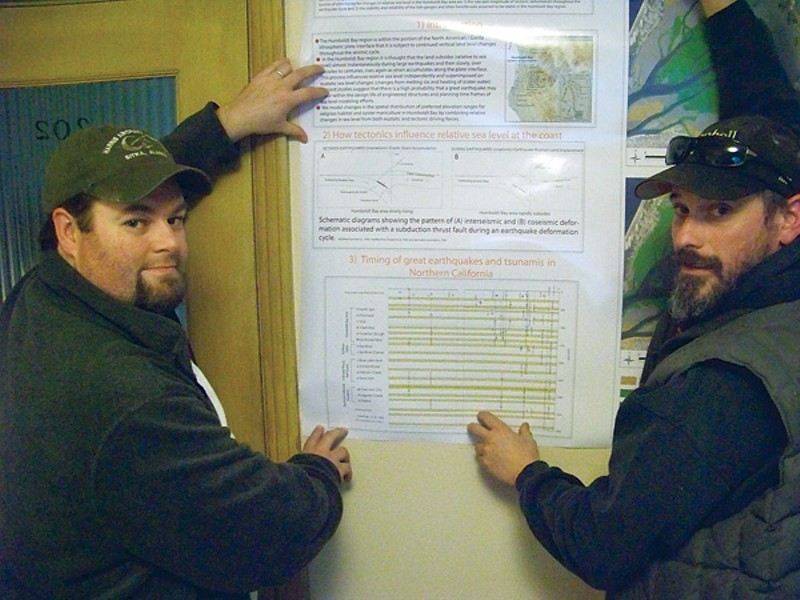

One recent afternoon, the three directors of the fledgling nonprofit Cascadia GeoSciences gathered -- Tom Leroy and Todd Williams in an office in Eureka, and Jay Patton by phone from Oregon -- to talk excitedly, voices rising, about their vision for getting planners to incorporate tectonics into their sea-level rise calculations. The three met as geology students at Humboldt State University in the late 1990s, and conceived of a nonprofit "devoted to multidisciplinary earth science-based research, restoration, education and outreach," as their mission states. Now they've formed the Humboldt Bay Vertical Reference System Working Group, into which they hope to lure more participants. They are interested in how vertical shifts in the land level around Humboldt Bay -- caused by movement along the Cascadia Subduction Zone, where the oceanic plate is diving beneath the North American plate -- influence sea-level rise. They got the idea after observing the work of another colleague, Whelan Gilkerson.

"Jay and I have been studying historic earthquakes, looking at this subsurface stratigraphy in Humboldt Bay," said Leroy. "Todd has been monitoring the larger plate boundary movements with these new high precision GPS machines, so he understands land level movement. And Whelan is studying biology and how sea level might affect different species, particularly eelgrass, in Humboldt Bay."

But Gilkerson was only looking at the effects on habitat from eustatic sea-level rise -- that is, the global increase in the ocean's volume. They thought it might be smart to try to superimpose land-level changes caused by tectonic activity upon eustatic sea level changes to arrive at a more accurate picture of what local relative sea level might be in the future around Humboldt Bay.

The last huge earthquake around Humboldt Bay was in 1700, said Patton. Scientists have determined that big quakes, of 8 to 9 magnitude, occur along the southern end of the Cascadia subduction zone -- our region -- at about 250-year intervals. So we're overdue, so to speak, for a quake that could vertically shift us -- and inundate us.

That's not all.

"The big realization we have had in the last couple of months is that not only do we have vertical deformation during earthquakes, but we have vertical deformation in between earthquakes," Patton said. That's the key new thing that we've been able to bring to the attention of people -- that there's ongoing land-level change."

In Arcata Bay, which includes Eureka Slough, there've been at least 10 major earthquakes along the Cascadia subduction zone that caused major subsidence in the last 4,000 years, he said. Some areas of Humboldt Bay subsided as much as three-quarters to one-and-a-half meters per quake. In between big quakes, the land level in subsidence zones goes up.

But other faults in the bay outside region complicate the picture.

"The problem is, the vertical deformation rate changes as you go across Humboldt Bay," said Patton. "In some areas it's going up, and in some areas we think it's going down, and we think that's related to those other faults."

Williams said they now want to resurvey all of the elevation benchmarks around the bay to see how much their positions have changed in the last 30 years, and then compare that information to what sea level has done in the last 30 years as well.

Washington and Oregon have actually already done this type or study, they noted.

So what does this mean for the Jacobs Avenue levee?

Look at the big picture, said Leroy. If there is a big earthquake that causes sea level to rise suddenly and inundate farmers, buildings, levees, salt marsh and the eelgrass in the bay, for instance -- all entities that have adapted to a specific controlled habitat -- there will be a scramble by all to reassemble and regain territory. The eelgrass and salt marsh will be at the mercy of the humans, whose structures determine where they can re-establish themselves, if at all.

"The place is going to be a wreck," Leroy said. "But we don't expect people to go, 'Omigod, we've got to move the levee system now,' and start this whole battle of property rights. What we're saying is, recognize that it's going to happen. Come up with some scenarios of what might happen, and then make what's called a pre-disaster mitigation plan. And that way the response isn't, 'Pave over all of these wetlands and slice the environmental permitting procedures.'"

Ron Harris strolled atop his stretch of the levee one day last week, stopped, and pointed along its long, curving arc. "Look at this dike," he said. "This dike is in beautiful condition. It can withstand another 25 years with no maintenance and it would be fine."

The tide was especially high -- close to nine feet -- but there were still several feet between the water and the top of the groomed, grassy levee. The water-facing side of the levee looked tidy, packed closely with large chunks of greenish rock. Harris said if sea level rises, just build the berm higher.

Harris started his Rainbow Self Storage enterprise -- the first self-storage facility in Humboldt County -- right here on Jacobs Avenue in 1975. He has 450 storage units here; the buildings lie just a bit below the high tide line. Some properties on the avenue are lower, and some higher. In 1990, Harris and nine other landowners got together and hired a contractor to beef up their portion of the levee. The contractor did a great job -- geofabric, rocks (although, the group was sued by the Corps of Engineers for a permit violation). It's even more tidy than the stretch alongside the Johnsons' properties, which Carl Johnson, Sr. upgraded in the 1970s. The rest of the levee looks less-maintained, and in some places is downright slumpy and brushy.

"We probably will want to get rid of that willow down there," said Harris, pointing to an overgrown section of levee west of his property. "They say water can travel along the tree roots, and that could weaken the dike."

Many of the Jacobs Avenue landowners have decided to pool $15,000 for an initial assessment of the levee, which Hank Seemann is arranging. They'll try to form a special assessment district. Assessment fees would help pay for upkeep, and a district might be eligible for funding that a private individual would not be. Plus, it could turn over permitting and other such chores to the city, perhaps. They're taking a phased approach: See what FEMA says (it's sending a crew out next month to investigate the levee), assess what it would cost to do the recommended work, and then find a way to do it -- and if they can't afford it, then agree upon the risk-reduction upgrades they can afford and do that.

Most of the landowners aren't sweating it. For one thing, they're used to working together -- most recently, they along with other business on the 101 corridor managed to convince Caltrans to include a stop sign at Jacobs Avenue in its preferred alternative for reconfiguring the corridor. Originally, all access roads were to be cut off except Indianola, which will get an interchange. For another, the levee seems sturdy.

"The good news about the Jacobs Avenue levee is it hasn't failed," Seemann said. "And it's only affected by the tides and by storm surges -- not by a river."

Unlike a river levee, which can be affected by sudden rises in hydraulic pressure, or water seepage beneath its impermeable clay core, or fast-water erosion, the lowly bay-mud Jacobs Avenue levee mainly deals with slow-moving tide water -- and gets tested by it twice a day. Wave erosion is the main concern, said Seemann. "And there is some of that happening on the toe, where the levee meets the mudflats of the bay," he said.

If the levee were to breach, and flood the avenue, there would be losses. Nick Rice, manager of R&S Supply, which sells roofing material on Jacobs Avenue, said they could lose $750,000 in inventory in a flood.

"That's pretty significant," he said one day, out at his shop. "Our trucks alone cost $160,000 each."

The Farm Store guys estimate that about $500,000 worth of their inventory is at risk -- it would hurt, but not sink them. Some, like Applied Industrial Technologies, a distributor whose goods are mostly in warehouses elsewhere, wouldn't lose much at all. Others, like John Ayres and his son down at the far west end of the avenue, could lose everything.

The Ayres have been putting the finishing touches on a new human crematorium there, set to open within the month. A flood would endanger a couple hundred thousand dollars worth of inventory, including the retort, in which remains are cremated. Presumably, bodies awaiting cremation might also be compromised.

"It would put us out of business," Ayres said on a recent afternoon in his new office, a hammer and a drill lying on his desk. "And I knew there was an issue out here, when I chose this location. But when you hear '100-year flood,' you don't worry much."

But Harris, standing atop the levee last week, said a flood would be an inconvenience and could damage some property. But it wouldn't be catastrophic.

"It wouldn't be like the floods we see on TV, where the buildings are all floating downstream," Harris said. "This slough is more like a lake. It would flood slowly. It would just be the tide rising, slowly, and then the tide would recede and it would go away."

He said the levee needs regular maintenance, for sure, and maybe more rockfacing and contouring. The goal is to protect their properties, FEMA or no FEMA.

And the big, looming earthquake? Harris and some other landowners turned fatalistic at the notion.

"If there's a big earthquake," said two of them, in the same exact words, "all bets are off."

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2