Even from the car, skimming fast south on Highway 101 in late December as the dusk sky streaked orange, you could tell something was different about Stone Lagoon, shimmering there behind a flickering screen of trees. It was breached! The smooth, silvery oval surface had grown a narrow, turbulent funnel that cut through the sand spit. The lagoon rivered through; the ocean pushed in.

This was exciting. Stone Lagoon doesn't breach every year. Unlike Big Lagoon, the larger body to the south which might breach as much as seven times in a year, Stone might open one year then go several more without breaching.

On New Year's day, a small group of breach seekers walked roughly four miles from Dry Lagoon north to Stone Lagoon. They followed the pretty sandspit between marshy Dry and the steep-beached ocean, then ascended into the hilly peninsula between the two once-joined lagoons. The trail, muddy and grassy in turns, passed through shady spruce stands, white-green corridors of huge, lichened alder, cedars, redwoods, salal, salmon berry, thimbleberry. Ferns everywhere. Rashes of mushrooms clustered on mossy tree roots. Scaffoldings of thick fungus plates rising up trunks. A pileated woodpecker knocked scarlet head into gray snag, chunking out square holes.

In late summer and fall, the place would be thick with berries and bears.

The group traversed down the slippery north side and emerged onto a slaty dark shore. It widened, changing to coarse pebbles and quartz chunks that grew finer-grained as they walked westward. Marshy grass and dune mat spread south toward the peninsula. Recently exposed beach expanded to the new waterline, plastered occasionally by small white bivalve shells.

Finally, the breach. They stood on a sturdy shelf of sand far back from the rupture. Below, smooth sand, crowded with gulls, fanned to the channel where the ocean pushed in.

What was coming in with it? What was going out? What happened as the lagoon level dropped? And when it closed back up, what then? Also (just asking), could you grab a shovel or apply a heavy boot and, you know, dig the thing open if you felt so inclined -- and should you?

The answer to those last questions, to be agate-eyed clear, is yes you could (and people have) and no, you definitely shouldn't -- for many reasons, including that you could be sucked in and spit out into the tumbling cold ocean.

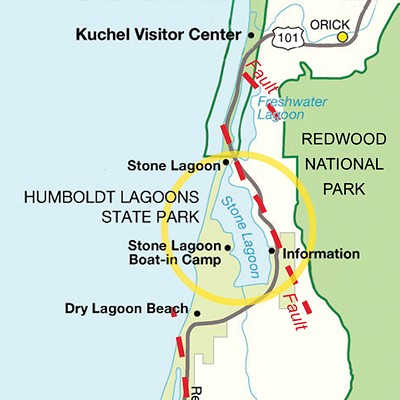

Coastal lagoons are common (in the United States, there are far more on the Atlantic coast than the Pacific). But the four in Humboldt Lagoons State Park -- Freshwater (co-managed by Redwood National Park), Stone, Dry and Big -- are unique in how they formed. And two of them, Big and Stone, might be the last naturally breaching lagoons in the state, said Michelle Gilroy, a biologist with the state Fish and Wildlife department. They are unaltered by human-made structures. (Freshwater is bounded permanently by Highway 101. Dry, which state park ranger Greg Hall said has been filling up more lately, was drained by early settlers to create land for crops and livestock.)

Stone Lagoon is the most enigmatic of the four. Freshwater is an easy adventure just off the highway. Big is enormous and much visited. Dry is a marsh -- a nice redoubt for elk and bird watchers. Stone is an astonishingly productive environment, better than the others, supporting more than a dozen fish species -- freshwater, saltwater and anadromous (which can live in both). It also has far more waterfowl than the other lagoons. And yet Stone's popularity, like its breaching regime, is intermittent. Flurries of interest gapped by long, quiet spells.

[][][]

Humboldt's lagoons formed in a mashup between several tectonic plates that continues to this day.

They are drowned river valleys created by low-angle, northwest-trending fold-and-thrust faults in the North American plate, said Humboldt State geology professor Mark Hemphill-Haley, whose work focuses on current earth movements, such as earthquakes. These faults occur as the Gorda plate shoves under the North American plate, at what's called the Cascadia subduction zone, causing it to buckle. Anticlines (hills) and synclines (valleys) form along these faults.

A belt of these fold-and-thrust faults, stretching from the Eel River Basin to a little north of Freshwater Lagoon, created such features as Humboldt Hill (an anticline), Humboldt Bay (a syncline), and the Humboldt lagoons, which formed in the bottom of synclines where rivers run down to the ocean.

"If you're looking northwest towards the ocean over Big Lagoon, the fault associated with it would be along the northeast margin of the lagoon, and trends northwest," Hemphill-Haley said.

Same thing at Stone Lagoon.

This particular fold-and-thrust belt is a unique structure.

"We're probably one of the only places where this fold-and-thrust belt is on land," he said. "Usually it's off shore."

What's happening is the Pacific plate, south of us, is shoving northwestward against the North American plate (at the San Andreas Fault), pushing the southern end of the Cascadia subduction zone landward. It comes closest to shore near Humboldt.

The spits closing off the lagoons are formed by ocean-borne sediments. As Humboldt State Professor Jeff Borgeld, a marine geologist who studies near-shore sediments, explains it, sediments flow out of the rivers and creeks, get transported by longshore currents and deposited by waves in a zig-zag fashion up and down the coast.

The Eel River, Borgeld said, supplies 90 percent of the sediment shoring up the beaches and spits between False Cape and Moonstone Beach, with some more added by the Mad River. The Klamath River and Redwood Creek supply most of the sediment building the beaches and lagoon spits north of Big Lagoon.

[][][]

Most of the time, the lagoon is quiet. Wild quiet, that is. Sure, there's Highway 101 over there, on the east shore. A small visitor's center nearby (closed now), a boat launch and a cabin where a state park ranger sometimes lives. There's also the little boat-in campground on the west shore, six spots nestled in a leafy bower of alder, willows and spruce. It, too, is closed these days -- the state's broke. But when it was open, you could row over with a batch of friends and, as the sun sank and the mist took over, it felt like you'd been flung into a remote past. The difficult access filtered out the bozos who'd bring stereos. And though you could still hear trucks on the highway, a mile away, their moaning on the downgrades just sounded like ghostly harbingers of a distant future.

There'll be no other boats on the water, usually. At least, not when Ken Bechtol comes out here. Even on a weekend. Bechtol's been coming to Stone Lagoon, on average, once a week for the past 10 years -- twice a week most months, less often in the winter. He'll bring a sailboat, sometimes, but more often one of the rowboats he built. Maybe the little white dory skiff, or perhaps one of the Whitehalls -- elegant, 12- to 14-foot numbers patterned after the livery boats that used to ply back and forth between ships, delivering people and goods, in the 19th century's New York Harbor.

Usually he'll row from the launch to the south end of the mile-and-a-half long spit. If it has breached, he'll swing far to the side before landing. Then he'll walk over and watch the lagoon communicating with the ocean.

Then maybe he'll row to the middle of the lagoon and stop. He doesn't fish. Just watches. Listens. There will be muddles of bobbing black coots. Sleek, curved cormorants. Kingfishers, treelimb-perched then suddenly diving. Ospreys scooping up fish -- each orienting the catch lengthwise in clutches so that bird and fish, aligned, cut neatly through the air. The fog might roll in low, opaque. But the lagoon is narrow, cozy within steep forested hills, and Bechtol is never lost.

In the winter, the whole hillside to the east will bristle gray where thickets of deciduous trees stand leafless. In the spring it'll turn brilliant green and stay green all summer.

The otters show up for a couple of months, some years. There are two families; one, a family of four, hangs around a little rock on the west shore, near the campground. They're elusive; one might poke a sleek head out of the water to eye you from 50 yards away, then slither back under water.

Sometimes harbor seals swim in, when the spit is breached. Bears often come down to the water, crossing the highway or descending from the hilly woods of the peninsula between Dry and Stone lagoons. There will be elk, when they're not lounging on the grass by the Little Red School House nearby.

Occasionally, Bechtol is popped from his reverie by gunshots: The duck hunters have arrived, in their boats (they can't hunt on shore because it's state park land. The waters of the lagoon, however, fall under state Fish and Wildlife jurisdiction). He might see park ranger Hall paddleboard over to check on someone's hunting license. And once, for about 18 months, Bechtol's solitude was frequently interupted by the exploits of a Coast Guard member, temporarily stationed at Humboldt Bay, who came to the lagoon with his performance kayak and whirred speedy laps around the bay.

There will be moonlight paddlers. And regular bouts of swimmers in the summer. Every year, one particular group of swimmers -- a competitive lot -- will arrive, fill the parking lot with their fancy Humvees and such, and for two days challenge each other, swimming rapidly across the lagoon.

Last July, Bechtol saw the Yurok jump dancers, something he'd never seen before. Nobody had, here on the lagoon anyway, in perhaps 135 years. There were at least six dugout redwood canoes. In several of them, men stood three abreast. They wore long dentalium shell necklaces and flared headresses whose broad, scarlet bands of pileated woodpecker feathers flashed against the misty gray-green landscape. The women, several sitting in one boat and one sitting in the front of another, wore traditional ceremonial dresses.

One of the men showed Bechtol, the curious boatmaker, the parts of a canoe, each representing a part of the human body. Heart. Kidneys. Lungs. Nose.

[][][]

It was Christmas Eve, 1985. Dan Doble and a friend were flyfishing in the south end of Stone Lagoon, and they hadn't had any strikes in a long while. They had just cast their lines out once more and, trolling along, were talking about heading to another part of the lagoon.

Then Doble had a strike.

"I thought I had hooked a steelhead," he said by phone from his home in Eureka recently.

He hauled it in. It was speckled like a steelhead. But it had two bright orange stripes under its jaw. "And when we saw the stripes, both of us were aghast. Neither one of us had ever seen a cutthroat that big."

It was 21 inches long. On their way home, they weighed the fish on a grocery scale at the market in Trinidad: seven pounds. After the holiday, Doble brought his catch to the state Fish and Game (now "Wildlife") office. It had shrunk a bit by then and weighed in officially at five pounds, 10 ounces.

It was still a new state record for coastal cutthroat trout, Doble said.

"The fisheries biologist, Ron Warner, he examined it and he was very excited," Doble recalled. "He made me a deal: He'd make me a fish print in exchange for letting him keep it for research."

Doble said if he caught such a big cutthroat today, he'd kiss the fish on the nose and turn it loose.

But it was a different time. Back then, you could use bait and barbs in the lagoon, kill and keep your catch. And the lagoon was stuffed with fish. (Today, while you can fish year-round on Stone Lagoon, you can only take two coastal cutthroat trout, no smaller than 14 inches, per day, and only with barbless hooks and artificial lures. You can't keep any other salmonids -- steelhead, Chinook, coho.)

Brackish lagoons are naturally highly productive. But Stone Lagoon seems an especially good place for fish, and fish food. Fish and Game biologist Mike Berry wrote in a 1997 management plan that the roughly 500-acre Stone Lagoon (its size depends on whether it's breached or not) supports 17 fish species, 16 of which are California natives. Many of these creatures are euryhaline, meaning they can exist over a wide range of salinity. Stone Lagoon ranges from 1 part per thousand salinity (when it hasn't breached in awhile) to 33 parts per thousand (the ocean is 35), according to a 1996 report by Robert Markle, who was a Humboldt State graduate student at the time.

Stone Lagoon also rarely goes anoxic -- devoid of dissolved oxygen -- Markle found. That happens when the denser salt water sinks to the bottom, along with organic matter, and a layer of fresh stays on top. As the organic matter decays it uses up the oxygen. This happens sometimes in Stone, but because it is fairly shallow (around 20 feet deep), the layers usually get mixed by wind in short time. In deeper Big Lagoon, the stratification tends to last longer.

Ross Taylor, a fisheries biologist who conducted fish studies in Stone Lagoon's watershed in the early 1990s when he was at Humboldt State, said Stone has high concentrations of algae, invertebrates -- including masses of polychete worms -- zooplankton and little bait fish that the bigger fish gobble up. And, even when Stone Lagoon becomes almost entirely fresh water, it tends to lose its salinity so slowly that saltwater fish trapped in there have time to acclimate.

"There's an incredible list of fish that have been found there," Taylor said.

The first year Taylor sampled the lagoon, its spit had been closed for three years. It had almost no salt in it. He found brackish and saltwater fish species living just fine alongside freshwater species: sculpins (freshwater), anchovies, starry flounder, English sole, four species of surf perch, surf smelt, night smelt, green sturgeon, Pacific herring, American shad, tidewater and all four native Pacific salmon species -- coastal cutthroat trout, steelhead, coho and Chinook.

"It was even documented that herring were successfully spawning in Stone Lagoon in nearly freshwater, at that time, which is almost unheard of," Taylor said.

In 1985, when Doble caught his big fish, the lagoon was especially stuffed. Fish and Game had been stocking it with hundreds of thousands of hatchery fish since at least 1940 -- mostly rainbow trout and steelhead (ocean-going, or anadromous, rainbows), Chinook salmon, coastal cutthroat trout and coho salmon. The fish came from hatcheries all over Northern California. Fisherman came from all over, too. There were fishing derbies.

It was a different time. But attitudes were changing. And trouble -- brewing for a long time in the lagoon's human-impacted watershed -- couldn't be masked much longer by indiscriminate fish stocking.

[][][]

Humans have been living at Stone Lagoon for thousands of years. Yurok people called the lagoon Cha-pekw 'O Ket'oh and lived there year-round. The Europeans arrived, cleared land, built homes, diverted McDonald Creek into a channel, and drained the already marsh-tending Dry Lagoon to raise crops and graze livestock. They even dug for gold in the lagoon's beach sands. And they renamed it, after a farmer from Massachusetts, William Stone.

There were still a lot of fish.

From 1903 to 1904, Eleanor Ethel Tracy, a 23-year-old from Eureka, taught at the Stone Lagoon School. Her letters home were compiled in a book called Schoolma'am. On Nov. 19, 1903, she wrote that it had rained nearly two weeks straight after a long dry summer, and the salmon were running up the overflowing creeks. Her boy students fished on their breaks. "The fish don't bite very well," she wrote, "but today they had pitchforks, and so managed to land four fine, large ones."

After World War II, things got worse, as large-scale logging of old growth redwood commenced, said Don Allan, who's director of the Redwood Community Action Agency's natural resources division. He was just a field specialist back in 1983 when RCAA began the first major restoration projects on McDonald Creek.

"The whole watershed was tractor logged in the '40s, '50s and '60s," Allan said. "The disturbance was pretty intense. Old aerial photos show that there were skid tractor trails everywhere -- straight up the creek channels, straight up the slopes."

The already unstable land -- uplifted ancient marine terraces, including the infamous Franciscan Complex "blue goo" -- got that much more slip-slidey. Massive volumes of sediment -- especially after big storms blew out badly constructed roads and creek crossings -- washed downstream, messing up creek spawning beds and filling in part of the lagoon.

Other private landowners logged, built ponds, planted non-native fish and grazed cattle along McDonald Creek and its north fork. There was even a private quarry, with a poorly built road, that supplied Caltrans with shale, Allan said.

In the 1980s and '90s, suddenly everybody was flocking to Stone Lagoon to try to fix it: California State Parks, which had been slowly buying up lagoon lands since 1931, state Fish and Game, landowners, RCAA, fishermen, university professors and their students, and more.

RCAA planted trees along the cow-denuded lower creek lands and built fences to keep the cattle away. The Stone Lagoon Action Committee formed. Its members fixed bad creek crossings, recreated spawning habitat, and got non-native fish out of manmade ponds. They studied fish habits, lagoon salinity and other phenomena.

And they tried to boost the population of coastal cutthroat. The species had declined in some areas of its range (which is from the Eel River in Humboldt County to the southern coast of Alaska). Before the stocking, it had probably dominated Stone Lagoon, said Terry Roelofs, a retired Humboldt State fisheries professor who, with graduate students, conducted studies there. Maybe the species could make a comeback there.

That turned out to be tricky, even after Fish and Game stopped stocking non-local fish. It turned out that cutthroat were breeding with steelhead and producing hybrids. That rendered the first breeding attempts -- in hatchboxes using eggs from fish in McDonald Creek -- untrustworthy. The second attempt -- hatchery raising pure-strain, wild cutthroat using eggs collected in uncompromised nearby watersheds -- yielded mixed results.

The tens of thousands of introduced cutthroat thrived in the food-rich lagoon.

"It was great fishing," said Taylor, who was one of Roelof's graduate students. "You could catch and release 30 to 50 fish a day. It was phenomenal."

But they still bred with steelhead in the creek; chances of a wild, self-sustaining cutthroat population, without hatchery help, seemed slim. Taylor thought the problem might be solved by removing some barriers in smaller tributaries in the upper watershed, where cutthroat could get away by themselves.

Then, around 1994, everything stopped. A landowner balked at the finger-pointing at his troubled land and booted the restorationists off. And the tidewater goby, a tiny anadromous fish, had been listed federally as endangered. The feds worried that the introduced cutthroat might gobble the goby up.

Since then, not a lot has happened fish-wise at Stone Lagoon. Gilroy, the state Fish and Wildlife biologist, said limited salmonid restoration funds have been diverted largely to the state-listed endangered coho salmon in other watersheds. But, she said, her agency wants to begin monitoring the lagoon again, in hopes of learning more about its fish -- especially the longfin smelt, an anadromous fish the state listed as threatened in 2009. She said she hopes anglers will start filling out those fish surveys placed in boxes at the lagoon. As well, the agency is keeping an eye on the New Zealand mudsnail, which recently invaded (see "Invasion of Big Lagoon," June 2, 2011).

State parks, meanwhile, has focused on invasive plants, and has nearly erased them from the spit, said environmental scientist Michelle Forys. She and her crew are now tackling invasives elsewhere around the lagoon. They also monitor the snowy plover, a federally listed threatened species, which sometimes nests on the spit.

[][][]

Condor sang first. That's the way one of the spirit people, the creators, had instructed long ago that woo-neek-we-ley-goo (now called the Jump Dance) should always start.

Then the people -- the Ner-er-ner (coastal Yurok) -- left the place where one of their ancestors' villages, Cha-pekw, once stood, not far from where Stone Lagoon usually breaches.

Women dancers sat in their canoes. Men dancers stood, three to a canoe, clasping hands with straight arms, raising them at times and then lowering them. And they boat danced across the water.

On the other side, they left the canoes and walked across the highway, with state and national park personnel, highway patrollers and several hundred other people looking on, including descendants of people who used to live in the villages at Stone Lagoon.

They danced in the field on the other side of the road. Then they climbed the ridge on rebuilt ancient trails. On top, overlooking Stone Lagoon, they danced. Then, following modern horse trails some of the way, they climbed another ridge, and there danced. Hundreds of tribe members joined them at times, even an elder in her mid-90s who walked the steep ridges with her family. They walked down to Redwood Creek, then up to Gans Prairie. Danced. And then the ceremony, which began July 20 with the new moon and ended July 29 close to the full moon, was done.

This was just last year -- the first time since the late 1800s that the people had had their jump dance at Stone Lagoon. The tribe hopes to revive a jump dance at Big Lagoon, next, said Chris Peters, a spiritual leader who is Yurok and Karuk. Traditionally, dancers from Big Lagoon and Stone Lagoon would begin their ceremonies on the same day, cross their respective lagoons, and converge upon the first ridge. Villages all along the coast would take part in jump dances, which originated on the coast at either Stone or Big Lagoon, said Peters.

The Jump Dance is an earth-healing dance, "a prayer for the continuance of human kind," he said.

Peters has worked with elders and others since the 1970s to restore traditional cultural practices. In 1984, they restored the Jump Dance at Pek-won, along the Klamath River. In 2000, they brought the White Deerskin Dance, also a 10-day ceremony, back at Weitchpec, where the Trinity River flows into the Klamath. It is a world-renewal dance. Both it and the Jump Dance, Peters said, are connected, and used to take place every two years. They are called high dance ceremonies.

"Not many other tribal nations in the world has that healing and renewing the earth as a central, philosophical approach to who they are as people," Peters said. "We -- Yurok and other groups here in Northern California -- that's why we're put here, to heal and renew the earth. It's our central purpose in life."

[][][]

A guy once told Don Allan that he used to gather butter clams on a beach at Stone Lagoon.

"And when the lagoon got full, he would not be able to get to his butter clams," Allan said.

So the man would take a shovel out to the spit and start the breach.

"I know a guy who did that with his boot," Allan added.

Terry Roelofs said he, too, saw a guy taking a boot to Stone Lagoon's spit. He figured the man would have been swept away if he'd succeeded.

"I've threatened lawsuits against one of my best friends for breaching out Big Lagoon," Roelofs said. "I was so pissed. It messed up a field trip up there at the lagoon. And he was so thrilled, so excited just to see it go! My concern was for waterfowl nests in that marsh out there. And when that thing is drained for the summer, it significantly reduces the surface area of the lagoon."

Someone breached the lagoon in the summer of 1993, just after hatchery bred young cutthroat trout had been planted in the lagoon. The next winter, Roelofs said, fish traps in the creek yielded just seven cutthroat -- there'd been more than 2,200 in there before the breach. The theory was that most of the planted cutthroats had gone through the breach (some were later seen in Redwood Creek). It closed, and they couldn't get back in.

Stone Lagoon won't breach naturally in late spring or summer. The water is too low. Both Big and Stone lagoons need the winter rains to raise their levels above the ocean. Then, lagoon water seeps through the sand, and washes over it, nibbling away. Once open, over a couple of days the lagoon level drops to sea level.

Big Lagoon breaches frequently because it has two big creeks flowing into it, filling it more often. Stone Lagoon just has McDonald Creek and its small north fork. Stone's watershed needs at least 60 inches of total rainfall in a season for the lagoon to breach, according to a breach study published in 2006 by Humboldt State student Jill Beckmann. This happens, she found, on average about two out of three years.

The irregular regime -- the timing -- at Stone Lagoon seems to work well for the creatures living in it. When it's closed, the fish and other animals grow and proliferate. When it opens, small creatures might get washed out, it's true. But big ocean fish ready to spawn can come in.

It stays open until the longshore currents and waves rebuild the spit again.

On Jan. 10, Ken Bechtol, the rowboater, wrote to a friend saying the breach at Stone Lagoon had closed. He was keeping an eye on it.

"At a 3.5 foot tide, wave wash just carried over to the lagoon side at 5 to 10 minute intervals," he wrote. "Water is just above previous breach level ... ."

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2