-

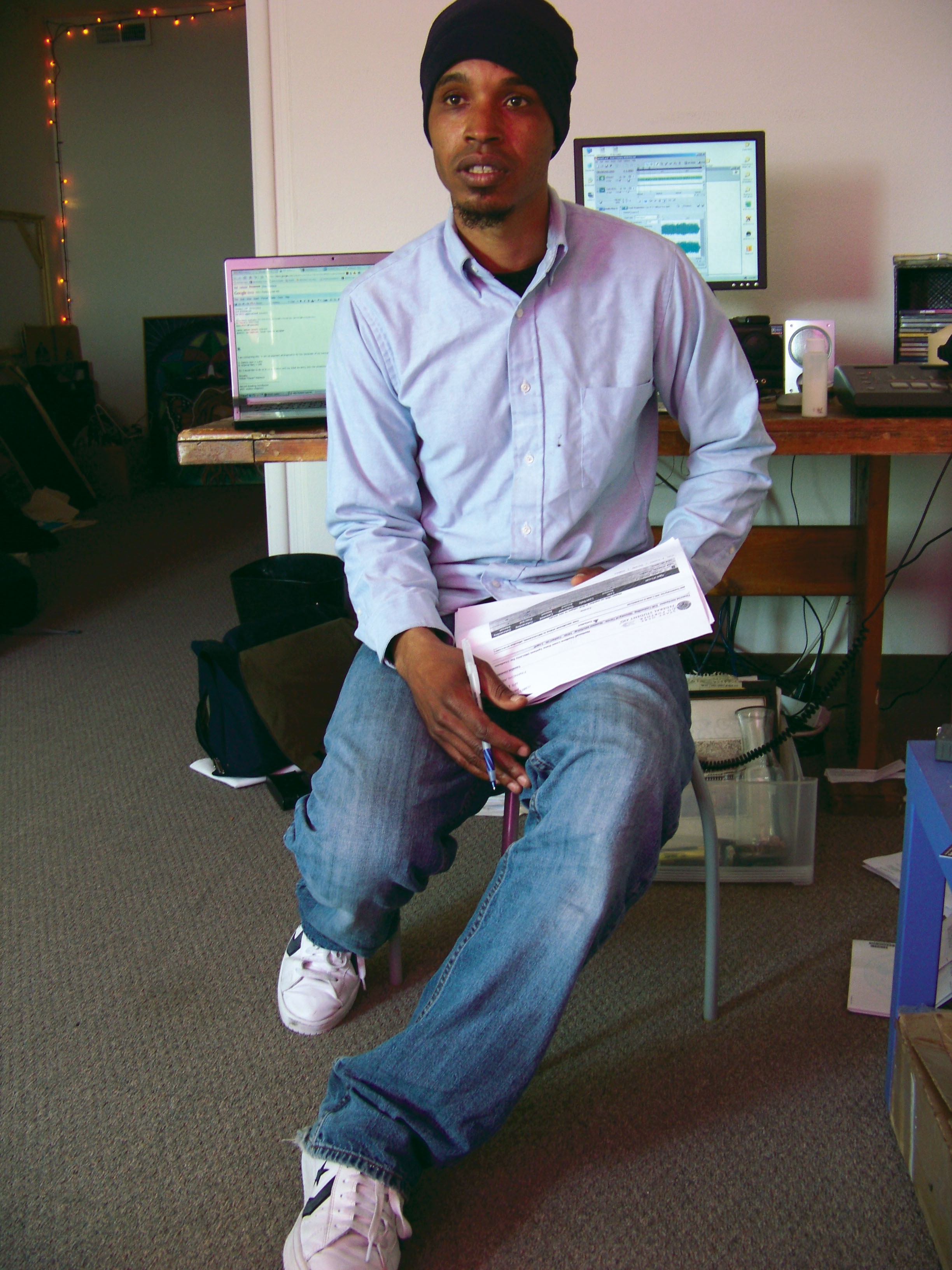

Photo by Heidi Walters

-

William Robinson advises young students not to quit college like he did. And definitely don’t ignore those student loans.

William Lamont Robinson admits that the first time he enrolled at Humboldt State University, in Fall 1991, he didn't care one whit about college. He was 19 and he'd come to play football -- which, he also admits, was sort of a last-ditch gamble. Humboldt wasn't exactly football central. But his football scholarship at East Carolina University had fallen through at the last minute.

"I had nowhere to go," said the personable, soft-spoken 37-year-old, sitting in a friend's art studio on Samoa Avenue one day last month. "And then Humboldt called me -- Coach [Fred] Whitmire called me -- and he said, 'Would you like to play for us?' So I just took it." He paused. "I think that was pretty much the end of my football career."

After a year, he dropped out.

"I just couldn't handle having a family at that age, going to school, football," he said.

He moved himself and his wife and baby son back to Merced County, where he'd grown up (on Castle Air Force Base) and gone to junior college.

Now, 18 years later, Robinson wants to re-enroll. He wants to get a degree through HSU's anthropology program so he can research what he calls "the thread of monotheism in all cultures."

"Monotheism to me is a great pattern," Robinson said. "It's sort of a yardstick of morals and conduct and laws. Throughout all my travels and learning and dealing with people, I found that the clearest path from A-Z is to stick to a code of conduct for myself. A moral code. A humanness. If I can come out of any relationship or any situation cleanly, then that leaves me in a better light as far as my next interaction. And I think that impulse, that thread, is there in all cultures, in the moral fabric of a society. And when that thread is pulled out, the culture unravels."

Trouble is, he may have unwittingly unraveled his own future when he dropped out of school and didn't look back.

Last October, when Robinson applied to re-enter HSU, he was accepted for Fall 2010. He was told he qualified for about $20,000 in financial aid. But then HSU locked him out of his online student account, barring access to his transcripts and other information, and said he couldn't enroll until he'd cleared a $1,824 debt -- $813 for his old federal Perkins loan, plus $200 for another loan, plus interest.

Robinson said he wants to pay the debt, but he can't right now. He can't even afford to make payments. His marriage ended last year, leaving him "emotionally and financially depleted," he said. His post-HSU years of raising three children and pursuing music, including pressing his own records and starting a Web-based business helping artists "place" their work, have been mostly lean. He was laid off from his last job, as a tech at Apple in Sacramento, last year, and he couldn't find a new one. Then he felt the pull to return to college.

Since moving to Arcata earlier this year, Robinson has been sleeping on fellow artists' couches, seeking help from the North Coast Resource Center, and filling out job applications. His $218 a month in unemployment benefits just ended. The only line on a job he's had is as a computing assistant at the student help desk at HSU, a position an encouraging professor who'd recently helped him map out a degree program directed him toward.

But he can't get the job until he's an official student. Robinson said he talked with Jan McFarlan, in HSU's financial aid department, about working around that obstacle.

"I said, can't they just give me a break, so I can start going back to school and get the job and then start paying back the loan?" he said. "She said no. 'It's been too long, William,' she said. 'You can't borrow it? Your ex-wife won't give it to you? She's not concerned about the father of her children? You can't borrow it from your parents?'"

She also told him he might not actually qualify for future financial aid because his loans defaulted, Robinson said. (According to online resources, there is a way to rehabilitate loans in such cases and remove the bad mark from one's credit. Robinson said he wasn't told about that.)

"And I'm thinking, can't I talk to somebody who looks at me like a real human being?" he said. "Someone who'd say, 'You've been through quite a load. Let's get you in school, see how you do.' I was looking for some sort of humanness. That thread."

McFarlan and others in HSU's administration refused to talk on record about Robinson's case, citing confidentiality.

Robinson says it was wrong to turn his back on the debt.

"Yeah, but some people, they spend all their money on partying," he said. "I wasn't like that. I was raising kids. And I was never locked up, you can't look at my record and see drug offenses."

He's not alone in thinking he deserves a chance. Dr. Abdul Aziz, a professor of business administration who befriended Robinson in 1991 but never had him as a student, said he thinks the rule of not letting a student in until he's paid off old debt in full can be "somewhat harsh," especially in hard economic times. And it might rob society of "a future excellent citizen."

"I am sure if he doesn't get admission he will go back to doing something which might not require any intellectual work or advanced type of work," Aziz said. "And if he is able to get into school again, and he's able to improve upon his skills to do some good work, well, you see, all of us are better off in that situation."

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5