Eight-year-old Lydia Kenyon stepped up to the microphone in McKinleyville Middle School's multi-purpose room, which was packed on this December evening with 200-odd community members -- teachers, students, administrators and parents, many of them upset, many downright angry. As she spoke to the McKinleyville Union School District (MUSD) Board of Trustees, Lydia sounded nervous and a bit sad.

"Please do not change the schools," she said. "I like my school just the way it is. I love Dow's Prairie so much and I want to stay there." Applause engulfed her as she stepped down and her father, Tom Kenyon, took her place at the mic. "I strongly oppose this idea," he said. "It would be a huge burden -- dropping off and picking up my kids at two different schools while working full time. It's important for my kids to go to school together. I will have that happen." This was a declaration. A line in the sand. He proceeded to lay out his arguments forcefully and defiantly. A kitchen timer rang, signaling the end of his allotted three minutes, and Kenyon wrapped up his comments with an ultimatum: "If these proposals go through, I will have absolutely no choice but to leave this district. I've already made my decision."

Raucous applause. Falsetto whoops of approval. Kenyon returned to his seat and another parent stepped up. "You have taken away our right as parents to choose how we want our children educated," she said, "and that is wrong." She was followed by a teacher, then another parent. One McKinleyville resident after another stepped to the microphone in a seemingly endless procession. A mom expressed fear for the well-being of her children. A teacher fretted that her wonderful school was about to be dismantled. Some people yelled. Many were in tears. The meeting, which had begun at 7 p.m., stretched toward midnight, and with each new speaker it grew increasingly clear: There is profound discord in the MUSD. Until recently, this rift has lain below the surface. But now, as the waters of funding and enrollment recede, the MUSD board finds itself faced with a decision that could very well spark a rebellion. If that sounds like an overstatement, you haven't talked to the parents.

To an outsider, the fear and outrage expressed at the Dec. 3 special meeting of the district board would have seemed all out of proportion with the recommendation presented that evening. A nine-person steering team proposed that for a number of reasons, the district should reconfigure two of its three schools. Dow's Prairie Elementary and Morris Elementary -- both currently offering kindergarten through fifth grade -- should be rearranged to form one K-2 school and one 3-5 school. (It hasn't been determined which school would go to which campus.) To understand why this recommendation seems threatening if not downright offensive to so many, you have to look at the history and character of each school, and of McKinleyville itself -- "where horses have the right-of-way," as the sign north of town reads.

If the community has a claim to fame, it's the totem pole that stands largely ignored in the parking lot of the McKinleyville Shopping Center. At 160 feet tall and 57,000 pounds, it claims to be the world's largest, and while its Native American pedigree is dubious (Ernest Pierson of Pierson Building Center designed it in 1962 to celebrate the shopping center's opening), the towering "potlatch" pole is an appropriate physical symbol for the town: Lay it flat and you have an approximation of McKinleyville's business district layout. The long, straight thoroughfare of Central Avenue has sprouted numerous fast-food joints and pre-fab metal buildings over the past 15 years, as McKinleyville became the county's fastest-growing community. Cul-de-sac mazes of tract homes have dropped onto cow fields with alarming regularity, yet McKinleyville remains unincorporated despite numerous efforts and a population that rivals Arcata's.

On clear days, an ocean breeze rolls up the bluffs, picking up scents of horses, cattle and dewy grass on its way into town. Hiller Park and the recently expanded Hammond Trail, leading from the Arcata Bottoms to Clam Beach, have helped McKinleyville earn a reputation as a pet- and family-friendly place, with relatively low crime and a neighborly, backyard-barbecue demeanor. There's even a lovely, if seldom seen, waterfall (its location guarded by those in the know).

For resident families, though, McKinleyville's most important feature is its school system. The three schools in the MUSD -- Morris, Dow's Prairie and McKinleyville Middle School -- have all been recognized as California Distinguished Schools. Generally speaking, parental interest and involvement run deep. (Note the aforementioned meeting.) So whence the discord? The answer is complex, but a good place to start is that long road bisecting town.

With few exceptions, Central Avenue serves as the dividing line for school attendance zones. If you live on the west side, your kid goes to Morris; if you're on the east, it's Dow's Prairie. Over the years, each school has developed its own distinct character. During the 1990s, Dow's Prairie came to be viewed as the "country club" school, drawing students from the more affluent neighborhoods on the east side of town. Morris kids, meanwhile, often came from families who lived in apartments and mobile homes on the west side. While both have the squat, utilitarian architecture of modern public schools, Dow's Prairie sits on a rural road north of town, tucked behind a thicket of evergreens, whereas Morris is in town, its playground flanked by triangles in pastels and earth-tones -- the roof-lines of surrounding tract homes.

"Historically, [Morris] has been 'the other side of the tracks,'" said Morris Principal Michael Davies-Hughes, a casual-but-serious man with a subtle Welsh accent. "Not so much anymore." As McKinleyville has grown, this socioeconomic imbalance has mostly evened out. The percentage of free and reduced lunches distributed at each school -- a telltale indicator of the poverty index -- is roughly equivalent. But for all McKinleyville's growth, its character remains that of a small town, and in small towns such perceptions die hard.

Add to this another division, one that developed -- was deliberately established, actually -- at Morris alone.

^^^^^

On a sunny January afternoon at Morris, fourth- and fifth-graders line up on a ramp outside a mobile classroom. Their teacher, Elizabeth Rivera, pushes past them to unlock the door, and the kids noisily file inside and find their seats. "Hola," she says to the students. "Silencio todo." The kids obediently quiet down. As class begins, she speaks to them only in Spanish. Drawing a diagram on the overhead projector, she explains the activity. "Vámos a comparar las dos películas con el libro." The students mutter amongst each other in English but clearly understand their teacher, who's labeling the three circles she's drawn on the transparency sheet. She asks a question in Spanish and a small boy in the back row spouts, "There's orange Oompa-Loompas in the old movie and in the new movie they're just normal colors." Rivera smiles, nods and writes on the diagram. After this exercise, a few students stand in front of the class and perform a short play, reading their highlighted scripts in flawlessly enunciated Spanish.

This isn't a Spanish class, though; it's a reading class that's taught in Spanish as part of Morris' Language Immersion program. Lots of other classes at Morris, including some in math, science, language arts and even P.E., are taught entirely en español. The idea is that students, beginning as early as kindergarten, will absorb a non-native language into their sponge-like brains simply by being immersed in it. These classes follow standard public school curriculum, only in Spanish.

According to former District Superintendent Skip Jorgensen, the Language Immersion program arose from a 1996 strategic planning session. The goal, he said, was for students to "experience another culture [and] see what life would be like when they go outside this area." Tim Parisi, former principal of Morris and current superintendent of the Arcata School District, said the idea was controversial from the start, with parents and teachers alike. But after extensive discussion and numerous meetings, the district board approved it. A research group looked at existing immersion program models and found an applicable one in Eugene, Ore., referred to as "50/50 Language Immersion" -- that is, half the instruction in Spanish and half in English.

The program was launched at Morris in 2000 with 40 kindergartners divided into two Language Immersion classes. Two "traditional" classes were offered for parents who opted out of LI, but many liked the new model. "It was well supported by parents," Joregensen said. "It's a very innovative, very different program for our area. It took off." Indeed, the program began attracting families from other districts, and those who embraced the program did so fully.

Now in its ninth year, the LI program has remained popular and has even been adopted by other area schools (Fuente Nueva Charter School, in Arcata). "[Morris' program] is the longest-running program of its kind in Humboldt County," Davies-Hughes said. "Last year we had 80 students enroll, which was 50 percent higher than the previous year." The program's success, he said, corresponds directly to that of the students. "[LI students] meet and exceed the proficiency requirements for the state. Not only are they learning a second language, they're proficient in their native language." Some in the initial group of LI students are now eighth graders at McKinleyville Middle School. They've been raising funds for a trip to Yucatán, Mexico, during Spring Break. "Hopefully the kids will be doing all the interpreting for us," said McKinleyville Middle School Principal Anne Hartline. "It's very, very exciting"

Results have not been as positive in Morris' traditional classes. There are a variety of reasons why parents opt out of the LI program: Some, especially those whose kids have difficulty with language to begin with, don't want to add an unnecessary challenge. Kids with learning disabilities tend to be put in traditional classes, as do most with behavioral issues. Some parents are skeptical of LI because LI kids lag behind in test scores for the first few years, though they tend to catch up later. And of course some parents just didn't like the idea of their kid speaking Spanish.

As the first LI students advanced grade levels, with a new group coming in each year, a pattern developed at Morris. The traditional students, generally speaking, came from households at a lower socioeconomic level than those in the LI program. Some lived in broken homes or had parents who were less involved. All of which fit into that old stereotype about Morris being the poor kids' school. "That perception is kind of a self-fulfilling prophesy, or a Catch-22," Davies-Hughes said, "because if we don't attract those parents who are involved, who maybe help to balance those classes out, then we're not going to change that balance."

Concerned parents who didn't want their kids in LI for whatever reason began to move their kids into Dow's Prairie. Families who were new to the area often heard about Morris' bad rep and deliberately sought housing in the Dow's attendance zone or applied for a transfer. This trend was magnified by the fact that many parents -- parents who actually wanted their kid in the LI program -- were denied. After students are past the first trimester of first grade, they are ineligible for the LI program unless they have prior Spanish experience. Unable to get their kids in LI and unwilling to put them in Morris' traditional program, these parents, too, chose Dow's Prairie.

Thanks to this migration, the once even balance of regular and LI students at Morris grew lopsided. In 2005, against the recommendations of a review team, Morris went from having two LI classes and two traditional classes to three LI and just one traditional for first through fifth grade, with no traditional kindergarten classes.

"We've had to continually re-analyze what we're doing and seek ways to improve the program," said Davies-Hughes. This move, however, had unintended consequences. Suddenly, all the traditional students at each grade level were lumped into a single classroom, and several grades were filled with the maximum of 20 students (per state guidelines), which meant that any new kid or any kid who wanted out of LI was sent to Dow's Prairie while the struggling underachievers in Morris' traditional class remained lumped together year after year. "You can imagine some of the challenges that come from that," Davies-Hughes said.

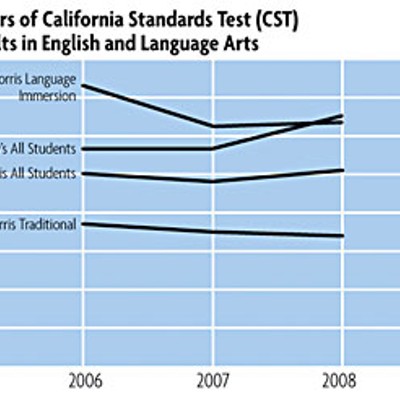

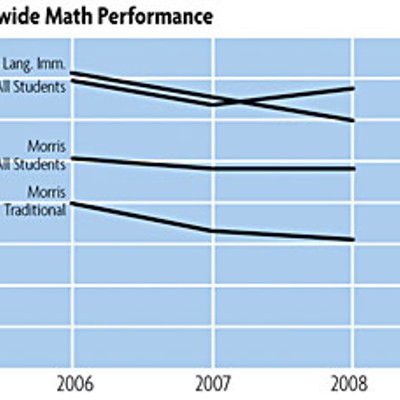

Phyllis Nolan, a Morris teacher for the past 20 years, doesn't have to imagine; she's seen it firsthand. "The traditional class became the dumping ground for kids being raised by their grandparents, kids from dysfunctional families, special ed kids," said Nolan. LI came to be seen as a school-within-a-school. "It's not what public education was meant to be," Nolan said. That disparity has been borne out in test scores. As Dow's Prairie and Morris' LI students have flourished, scoring well above state average in Standardized Testing And Reporting (STAR), Morris traditional students have floundered. Last school year, for example, while 65 percent of Dow's Prairie students tested at proficient or advanced levels in English Language Arts, and 63 percent of Morris' LI students reached that mark, only a third of Morris' traditional kids achieved proficiency. Math scores were similar: Dow's Prairie -- 67 percent proficient; Morris LI -- 60 percent; Morris traditional -- 31 percent.

Under No Child Left Behind, STAR results have grown increasingly important. "Each year, there's about an 11 percent rise in the percentage of students who are required to be proficient or higher," Davies-Hughes said. "We've had a plateau over the last couple of years, but this last year it jumped up about 11 percent, and now each successive year it's gonna be another 11 percent until 2014 when 100 percent of our students, including special education students, are expected to be at proficiency as measured by STAR."

Those benchmarks are wholly indifferent to budget cuts. MUSD Superintendent Dena McCullough said the district is bracing for $600,000 in cuts next year, while mid-year cuts this year will likely be around $350,000. "That's anywhere from $300 to $400 per student," McCullough said. Thanks to strategic planning and careful budgeting, she believes that MUSD is in better shape than most districts in the county, but Davies-Hughes said the future still looks grim. "We're operating a pretty bare-bones operation," he said. "The state's accountability measures keep rising, and we're expected to do more with less."

Facing declining enrollment numbers, a shrinking budget, a disruptive number of transfers and a profoundly struggling group of students, the district board realized that something needed to change, and fast. Out of last year's strategic planning sessions, a nine-person steering committee was formed to seek a solution. The team included McCullough, Davies-Hughes, a teacher from Dow's Prairie and one from McKinleyville Middle School, a Morris parent, a district board member, a maintenance staffer, the district business director and a community member. Four assessment teams also were formed to gather key information. In all, more than 50 people have spent nearly 11 months assessing the situation -- conducting data analysis, interviews, surveys, focus groups and community forums.

The steering committee analyzed a number of reconfiguration models, including a K-8 immersion school and a charter school, examining each from a purely logistical perspective. "We looked at just the facts," McCullough said. "Could we hold the students there? Would funding change? We looked at the facilities themselves." Ultimately, a number of configurations were nixed as impossible, and the K-2, 3-5, 6-8 model emerged as the best solution in the eyes of the steering team. Language Immersion would continue as a separate but parallel program spanning the schools.

"We eliminated those [other models] based upon facts, not opinions," McCullough said.

^^^^^

This was a distinction McCullough hastened to make in her opening remarks at the tumultuous, marathon special meeting of the MUSD board in early December. Two community forums at Dow's Prairie had given her a sense of that community's resistance to this new idea, and McCullough stressed at the outset that the steering team had not reached its conclusion lightly. "I'm not sure if we can adequately express how much information and thought went into this process," she told the packed multi-purpose room. "There were tears and a lot of intense discussion, but ultimately we felt we were making this recommendation based upon what is best for all students."

Davies-Hughes quoted then-Vice President-elect Joe Biden. "'You are entitled to your own opinions, but you are not entitled to your own facts.'" (This assertion was met with stone silence.) He argued that reconfiguration has the potential to address many if not all of the district's key issues. The struggling students could be spread out and thus benefit from the example of their higher-achieving peers. District transfers would be eliminated, staff consolidated and resources maximized. The sense of competition between the two schools would be gone. It was the steering team's position that this new configuration should be established by the fall of 2009.

The first person to step up for public comment was Cindy Wilcox, a paraprofessional, volunteer and mother of a third-grader at Dow's Prairie. "Can I see a show of hands of Dow's parents who received a survey?" she asked. Most kept their hands down. "I didn't either." Turning to the board she said, "I'm afraid to say that the facts you're working with may be a bit biased. I appreciate the work that's been done," she said, "but at Dow's Prairie we've worked really hard, and we don't have the issues that Morris is having. ... We parents love Dow's Prairie. I think the public is speaking to you," she told the board, "and I hope that you're listening."

The applause was explosive, and for the next four hours, people streamed up to the microphone, the vast majority of them from the Dow's community -- teachers, parents and children pleading with the board to leave their beloved school alone. Clearly the model at Morris was not working, they said. Many of them blamed the Language Immersion program, saying that Morris' problems simply proved that the district isn't big enough to support it. Why, they asked, should the failing model be spread around the district? Keep the problems contained at Morris, they begged, and leave us alone.

"When that meeting happened, I think a lot of parents and teachers were caught off guard," said Nancy Lien, a substitute teacher and Dow's parent. "We reacted in a very emotional and passionate way. We weren't trying to talk badly about the Language Immersion program. We weren't against Morris. And we don't just want to complain; we want to help." Still, Lien unequivocally stated, "We do not want reconfiguration."

Not everyone at the meeting was against the idea. Phyllis Nolan, the veteran Morris teacher who this year is teaching in the LI program for the first time, stepped to the microphone as the first (and one of a very few) to speak in favor of reconfiguration. "Suffice it to say it is painful to listen to everything that's being said tonight. I know those children," she said, referring to the traditional kids she taught for nearly two decades. "They're the kind of children you want to take under your wing. Arguing to keep Morris untouched is not caring for those children. Morris alone cannot fix this district problem."

Terrie Smith, president of the MUSD Board of Trustees, said the meeting was likely not a representative sample of opinions district-wide, with the Dow's crowd vastly outnumbering Morris'. Nolan agrees. "The parents that the board needs to hear from are those traditional kids'," she said. "But those are not the ones who write letters or get to parent conferences. They're at home, struggling to get dinner on the table."

Regardless, for Dow's parents like Tom Kenyon, the man who drew a line in the sand, the issue is not debatable. "If they split the schools up, I'm out," he told the Journal last week. "And I know six or seven [other families] off the top of my head that would send their kids to other schools. That's just in the circle of people I know, and they're all dead set on it."

Dow's Prairie Principal Jane Rowland said she sympathizes with these families. If the configuration goes through, she said, "I know a number of them will [leave]. And these are wonderful, wonderful families. I'm very concerned. Dow's Prairie seems to be working for a lot of families, and they're looking out for their own child." Davies-Hughes said the district must look at the big picture and not be swayed by threats. "You know, parents' opinions and passions certainly have to be accounted for and taken into consideration," he said, "but it can't be the overriding principle or driving force behind the decision."

The MUSD board did not make a decision at that December meeting, instead asking for more information, including a more detailed cost/benefit analysis of the reconfiguration plan. They also asked for a subcommittee to take one more look at the current K-5, K-5 configuration to see if it can be made to work after all. That group will present its findings to the steering committee, which in turn will present them to the board. The information will be posted for public viewing on the district's Web site (www.nohum.k12.ca.us/msd/) by Feb. 6, and another meeting of the MUSD board is scheduled for next Wednesday (Feb. 11) at 6:30 p.m. The district's January newsletter advertised this meeting under the header, "RECONFIGURATION DECISION." Whatever that decision, it's not likely to be greeted peacefully.

^^^^^

Yet within this polarizing debate, there are those advocating compromise. Tawnya Rourke Kelly, vice president of Morris' Parent Teacher Organization and participant in the strategic planning process, said in an e-mail to the Journal that the proposed reconfiguration "is not an idea I love. I admit, it will inconvenience me." But she feels her own inconvenience is outweighed by the needs of the district, and that arguing about how things got to this point is futile. "Whether the Language Immersion program's existence has caused the logistical and social issues that have arisen in the district is moot, in my opinion," she wrote. "It is an immensely valuable and effective program, and it draws numerous families into this district."

She sees the passion of McKinleyville's citizens as a resource rather than an obstacle. "[W]e are particularly blessed with a dynamic, gifted group of educators, and many passionate parents. To me, that is a recipe for success. I think that the amount of emotion surrounding this issue will ultimately be re-channeled into a very positive workforce of people to help create a better, more efficient school district."

That harmonious existence may take time. "Regardless of what happens and what decision is made, there are gonna be unhappy people," said Davies-Hughes. Board President Terrie Smith, who has two of her own kids in LI at Morris, said she's well aware that the verdict could spark outrage and perhaps an exodus. "I would hope [parents] stop and reflect before they jump ship and instead think about how they could make this district and this community better," she said. "This process we're going through -- as difficult and as painful as it is -- it's time." With resolve and surprising confidence, Smith declared, "We will do what's best for the kids. That I'm sure of."

Cindy Wilcox, the mom who was first in line to speak against reconfiguration in December, said she'll show up to Wednesday's meeting with an open mind. "I think people should be there, and even if it's a decision we don't agree with, we should keep talking," she said. "That will be far more effective than leaving the district. We should remain a community school and act as a community."

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2