The blue heron, legs spraddled for balance, tipped its long body forward into a horizontal crouch and stretched its neck and head out. Statue-still as the Mad River twirled past. The water moved gently, at autumn speed, and pooled in an eddied quiet around the twig-addled nub of rock where the heron waited. The pool erupted in tiny fountains, plip plip plip plip plip; the fish jumped all about, but the heron didn't twitch.

"The ultimate fisherman," said Barry Van Sickle, superintendent of the Humboldt Bay Municipal Water District, watching the heron from the deck of the district's industrial water diversion works on the opposite bank. He waited, expecting the heron to suddenly strike, swift and efficient. But it didn't. "Although, he's studying it pretty hard," Van Sickle finally said. "He's not doing much today."

Studying and studying. Watching and waiting. And the heron's not the only one pondering the waters of the Mad, and the opportunities and challenges within, so intently these days.

A couple of weeks ago, Carol Rische, general manager of the Humboldt Bay Municipal Water District, got a call from Terry Spragg. He was wondering, said Rische in a recent interview, whether the district would be interested in letting him do a waterbag demonstration. He'd fill up his innovative Spragg Bags with Mad River water and float them in the ocean to San Francisco. And if it impressed the district and some other municipality -- say, Marin County, or Monterey -- maybe the municipalities would enter into a water transfer agreement with each other, and he, Spragg, could be the transporter. He'd already contacted Marin and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, and even had a chat with some local folks about using their dock on the Samoa Peninsula.

The time was ripe: California's water crisis was deepening. Coastal towns were talking about building expensive desalination plants, and one was already in the works in San Diego County. The state, meanwhile, needed to shore up or rejigger the 50-year-old water works that delivers the majority of the state's precipitation, in the north, from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta at San Francisco Bay to Central Valley farmers and 22 million customers farther south. And the Bay-Delta ecosystem was collapsing, hurting protected fish like the Delta smelt and salmon; the Sacramento's salmon fishery, for that matter, was kaput. A third year of drought plus environmental concerns had led to water curtailments to farmers and declarations of drought emergencies in 50 of the state's 58 counties -- including Humboldt, whose town of Redway relies on the shrinking South Fork Eel River.

Meanwhile, other major water supplies -- from the Colorado River, from the Owens Valley -- had diminished, the state's population continued to grow, global warming promised more drought and floods, and a levee-busting earthquake could happen at any moment.

Legislative leaders and Governor Schwarzenegger bickered behind closed doors over everything from stiffer water conservation rules, to building two new dams and a peripheral canal to carry more water around the Delta, to seeking over $9 billion in bonds for the fixes -- something the state treasurer warned might not fly with debt-shy voters. At one point, two weeks ago, the Governor even held hostage the 704 other bills that the Legislature had labored over, saying he'd veto them all if they couldn't agree, pronto, on a water plan.

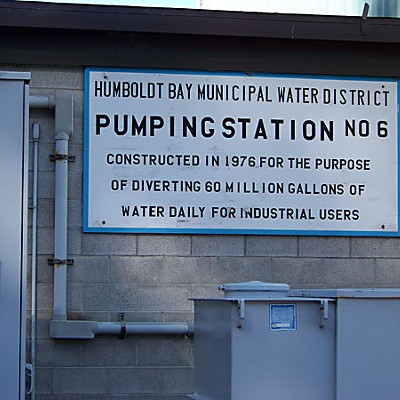

Spragg, however, had read a newspaper account of HBMWD's latest troubles of quite the opposite nature. Its last industrial customer, the pulp mill, had closed and the pumps that had diverted Mad River water to the mill were now completely turned off. That left the district with millions of gallons of unused water capacity. Also, the mill had paid 45 percent of the district's costs; now the district's seven municipalities -- serving 80,000 customers -- had to shoulder the burden. And their costs had already tripled since 1999, after another mill shut down and the remaining mill reduced its water usage.

More seriously, in the longer term, if the district didn't find a new customer for the industrial water it could lose control of that water under California's use-it-or-lose-it doctrine governing surface water rights appropriations.

Actually, this wasn't the first time Spragg had called the district. He called last year around this time, right after the mill closed. And he's been calling every other year or so for the past 10 years, said Rische -- ever since the other mill, owned by Simpson, closed.

"We had about five, six, seven guys knocking on our door, and some of them had the waterbag technology," said Rische. "As I understand it, San Diego was willing to see a demonstration project, and Terry was one of those first folks knocking on our doors."

Nothing came of it -- and as many in Humboldt know, another waterbag schemer, Ric Davidge, soured the community on the idea. Who could forget the hue and cry over the Mad Water Grab?

When Spragg called Rische this time, she said, she told him the district and its board were developing a water resource plan, in which the public would play a heavy role in developing options for what to do with its water. It would take some time. It may or may not involve water transfers.

"I told Terry again what the Board last year had formally communicated to him ... basically, "Don't call us, we'll call you," said Rische. "Let this thing play out, and see what the public has to say."

This month, and in the months ahead, the district is convening public meetings to let people help fashion how the district will go about judging proposals for what to do with the industrial water capacity freed up by the loss of the two mills -- 60 million gallons a day. The next meeting is this Thursday, Oct. 22, from 6 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. at the Wharfinger Building in Eureka.

An advisory committee has come up with initial evaluation criteria, and now citizen groups and the general public are learning about the issue, and critiquing the criteria. By December, the criteria will be chosen. By January, citizen groups will begin generating actual options. Broadly, those could be anything from finding local industry to buy the water, selling the water outside the area, leaving the water in the river for the fish, or doing nothing and losing local control of the water.

But do we have time for very much pondering? The district's state water rights permit was recently renewed until 2029, but anyone could petition for that industrial water sooner and try to prove they have a reasonable and beneficial use for it. How will greater California's water crisis influence our water crisis? Should we be building giant straw deflectors? Waterbag piercers? A hedge of protection around the Mad River?

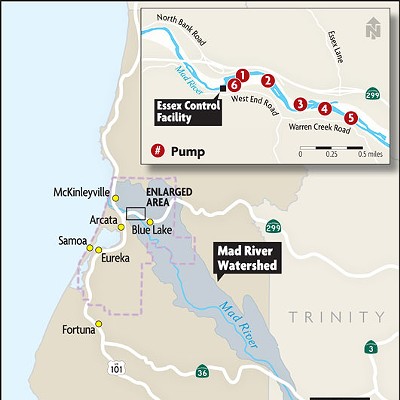

Actually, the Mad River already is hedged in by geographic and legal protections. It begins in Trinity County and flows northwest into Humboldt County where, about a hundred miles later as the crow flies, it empties into the ocean north of Arcata. It drains a watershed of about 500 square miles and discharges about 1 million acre-feet of water to the ocean a year. It has numerous small tributaries but connects with no other major river system.

Unlike the Eel, Trinity and Klamath rivers, which have upstream diversions that take some of their water out of the basin, the Mad River has no upstream diversion and no out-of-basin transfers.

It does have a dam, which captures 2 percent of the watershed's runoff in Ruth Lake Reservoir in the winter. In the summer and fall, water is released to run 75 miles down the river to the diversion works at Essex, nine miles from the mouth.

Unlike other diversions, the district puts water into the river at a time of year when, under a natural regime, it would have been low or dry. During full capacity use -- 60 million gallons a day of untreated surface water going to two mills, 20 mgd going to replenish the groundwater pumped from beneath the river and treated for municipal customers -- the diversion would amount to 6 percent of the river's average annual discharge. Now, without the mills, the diversion is 1 percent.

At one time, the state Department of Water Resources -- which manages the state's water resources distribution -- planned to build water-gathering facilities on our North Coast rivers, including on the Mad, as part of the State Water Project, says fisheries consultant Bill Kier.

"In 1970 the State Water Resources Control Board 'backburnered' it because of a slow-down in southern California's population growth," Kier said last Monday, sitting by a window in his Blue Lake house with a view to a small greenbelt where autumn-red poison oak laced the trees and a birdfeeder hung, busy with juncos.

Kier runs a consultant firm that specializes in river and salmon restoration and conservation. But from 1957 to 1983, he worked for a succession of California gubernatorial administrations, starting out with Fish and Game in the Pat Brown administration -- a time Kier calls the "age of innocence" -- and ending as an environmental policy advisor to the Senate under Jerry Brown (the "age of enlightenment"). In Ronald Reagan's administration ("innocence"), 1964 to 1974, Kier helped draft the legislation that would form the SWRCB, which manages water rights. He likes to note, incidentally, that nearly every administration since the late '50s has heralded a peripheral canal as it lurched out the door, but it's never happened. "It's like Groundhog Day, without the laughs," he said.

Before the state could resume its plot to divert the Mad into the big state waterworks, the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act snapped up several North Coast rivers, including the Klamath and the Eel, and that was that. Although the Mad wasn't designated Wild and Scenic, it was now surrounded by watersheds that were and where no new infrastructure could be built.

Because of this isolation, and also the local bent toward keeping things local, Kier doesn't think there's a major threat to the district's water rights or even of the water being sold south. The only likely way to export that water from the basin would be by sea.

"I don't see any marketability," he said. "Because of the isolation, and because even though the average water wienie would have been a drop in the bucket, still people went ballistic."

He'd actually like to see the water rights be transfered to in-stream flow reservations to restore the river -- especially in the gravel reach in the lower section that's been heavily mined -- and create a salmon refuge. But that would be augmenting natural flows, which alone might fall under the California constitution's prohibition against wasting water.

The Mad above Ruth Lake typically goes dry in the summer. The boulder-choked, steep-sloped middle reach below the dam is inaccessible to most fish. And the lower reach is riddled with mined gravel bars and was damaged in past manipulations and floods. The river has few tributaries useful to fish except Lindsay Creek. In the old days, salmon could be scooped up in nets near the mouth and estuary -- and in years when low flows allowed the sluggish river to close off at its mouth, fishermen would dig an opening so the salmon could get in. The river's salmon populations are still recovering from being overfished in the late 1800s, says the water district's habitat conservation plan. Only the hatchery steelhead are thriving.

But because of the district's summer and fall releases for consumptive use, which flow down the river, at least the river isn't plagued with blue-green algae blooms like other local rivers.

California law does allow water rights to be transfered for fishery enhancement. But the entity wanting to put water in a river for in-stream fish flows has to have control of the system -- i.e., have a dam, which the district does. But determining how much water would be considered beneficial for fish might stumble up the state, Kier said, which for years has evaded committing to such an investigation river by river.

Still, Kier thinks the idea is possible.

"I'm saying, let's try something just particularly, specially Humboldt, let's try to secure a right for fish restoration, for salmon restoration," he said.

He thinks it may be a good time to do it, with the prospect of Jerry Brown becoming governor -- bringing us out of, you got it, the "dark ages" -- seeming more and more likely.

As for the rest of California and its water troubles? "It's going to rain," he said.

Kier's idea wouldn't preclude the water's going to a paying customer at the end of its run. But the fish flows are the thing. "The district's prudent capital reserve/replacement budget will have to come almost entirely, in my view, via one painful rate increase after another, until water service costs here approach those of more populous areas, like Sonoma County, where finished water costs roughly twice what it does here," he wrote in an e-mail to Aldaron Laird, an environmental planner from Arcata who serves on the HBMWD's board.

Laird had written to him that the in-stream flow idea might be difficult to get permitted, and also that it wouldn't solve the district's cashflow problem.

In an interview a couple of weeks ago, Laird said one idea he had was that the district could build a second hydroelectric power plant. It already operates a two megawatt one at Matthews Dam and sells the power to PG&E. The district could build a second plant down at Essex where the diversion works are, run the industrial water supply down the river and through the second plant and sell more electricity.

The tricky part, he said, would be that more water would be going to the estuary than natural flows -- which is sort of what's been happening lately anyway since the mill shut down, but which the state might frown upon. And, how would the ecosystem react?

"I asked some estuary scientists what they thought, and they said it would be neat to study it," Laird said.

But the main concern now, Laird said, is finding out what the ratepayers want.

"I went to the water rate hearing in Blue Lake the other night, and I got the sense that if all were asked if they wanted us to find another pulp mill, there'd be a resounding 'Yes!'" Laird said. "The story is, we built this great system, and we need to sell the water."

Voters resoundingly approved formation of the HBMWD in 1956 and bonds to build a regional water system. They liked the idea because it would bring in pulp mills that would not only burn wood waste more cleanly than the air-fouling teepee burners, but it would pay a good chunk of the system's upkeep. And the cities would get clean, treated, pretty cheap water -- Arcata and Eureka initially, but now Blue Lake and the McKinleyville, Manila, Fieldbrook-Glendale and Humboldt community service districts are on the system, plus a couple hundred small retail customers.

Without the mills, the individual cities wouldn't have been able to afford such a system, nor get water as cheaply, nor keep up with increased regulatory and power costs, said board member Bruce Rupp.

"When I first came on the Board, in 1995, it cost $13,000 a year to meet the regulatory requirements of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission," Rupp said. "Now the FERC regulatory costs this last year were about $120,000. And in every aspect of what we do where we interface with the state and federal government, costs have increased and those are all passed on to our ratepayers."

The district had to build a state-mandated turbidity reduction plant in recent years, much of whose $12 million cost was borne by the ratepayers. Looking ahead, the municipal side of the system alone will need millions of dollars in repairs and upgrades over the next 10 to 20 years.

Spragg Bags to the rescue? With their 1,000-pounds-per-inch durability and massive zippers that have been MIT-tested? Zip a bunch of those babies together and you'd have your own water railroad.

Rische and the board members aren't ruling anything out.

"We are exercising due diligence, with respect to the water rights and the water resources, to protect and look after our interests, and the ratepayers interests and our communities' interests," Rische said. "If an opportunity presents itself for an out-of-area sale, that would be considered."

In due time, of course. And Spragg, reached last Friday, said he doesn't think there's any great pressure from the outside for Humboldt's water "at this time."

He has been contacting municipalities in southern California and along the coast for a long time, however. Some haven't responded. But last May he did get a letter back from the Metropolitan Water District's general manager, Jeffrey Kightlinger, who wrote: "We have reviewed your proposal to the Governor's Delta Vision Blue Ribbon Task Force regarding a test of waterbag technology emergency applications in the Delta. Please feel free to inform the Task Force that the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California has reviewed your proposed waterbag technology and concluded that it is feasible and could potentially be applied for either emergency use or regular water supply."

Other than a demo he did in Washington state some time back, Spragg hasn't secured a contract to transport water in bags from A to B. Although, he said he chatted last week with Security National's Randy Gans about the possibility of using the company's dock to load and ship the waterbags if he does a demonstration here.

He doesn't see why people aren't leaping at his proposal. Desalination costs up to $1,500 an acre-foot, he said, whereas he believes water transported from Humboldt in bags could cost less than $1,000 an acre-foot. And he's not, Spragg insists, like that other guy who came here and wanted to buy the extra water and then turn around and sell it to the highest bidder. The only thing they had in common was waterbags.

"I'm trying to work with the local community," he said. "I'm in the transportation business. My goal is to get at least one California water district to make contact with Carol Rische."

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4