Late in the afternoon, on Nov. 19, 2010, seven agents from the Humboldt County Drug Task Force checked in to seven rooms at the Anaheim Hilton. The elegant, glass-covered hotel sits directly across the street from Disneyland. The suites -- four with king beds, three with a pair of queens -- were on the fifth floor. Upscale but not ostentatious, they were furnished with flat-screen TVs, stainless steel appliances and ebony-veneered furniture. Sliding doors led outside to the open-air Lanai Deck. The temperature hovered in the mid-60s, likely too chilly for the agents to take advantage of the deck's pools, but the hot tubs would have steamed enticingly. At night, the lights from fireworks over Disneyland reflected in the windows and backlit the rows of palm trees surrounding the parking lot.

The agents were attending the California Narcotic Officers' Association's 46th annual training conference. During the three-day event, they each took six four-hour workshops on topics of their choice. Event organizers encouraged attendees to bring their families. While the cops learned about outlaw motorcycle gangs, the occult, Mexican cartels or how to make meth, their spouses and kids could go to Disneyland, or lie around and watch HBO and order room service. In the evening, special events gave attendees time to unwind together. The first night they attended a law enforcement trade show. The next they feasted at a banquet. The third night was entertainment night; Mixed Martial Arts fighters came to the hotel to sign autographs and watch tapes of past brawls.

The rooms were pre-paid. Back in June, the drug task force secretary sent a memo to the county auditor's office requesting a check. The seven rooms cost $170 per night, for four nights, plus tax, totaling $5,506.20. She sent another memo requesting $3,390 to cover the agents' $495 tuitions for the conference. The auditor's office cut both checks, and the money was withdrawn from Special District Fund Account 3644. All the money in that account -- money that paid for the conference tickets, the views of Disneyland, the mints on the pillows -- was taken from someone months earlier, seized by the drug task force.

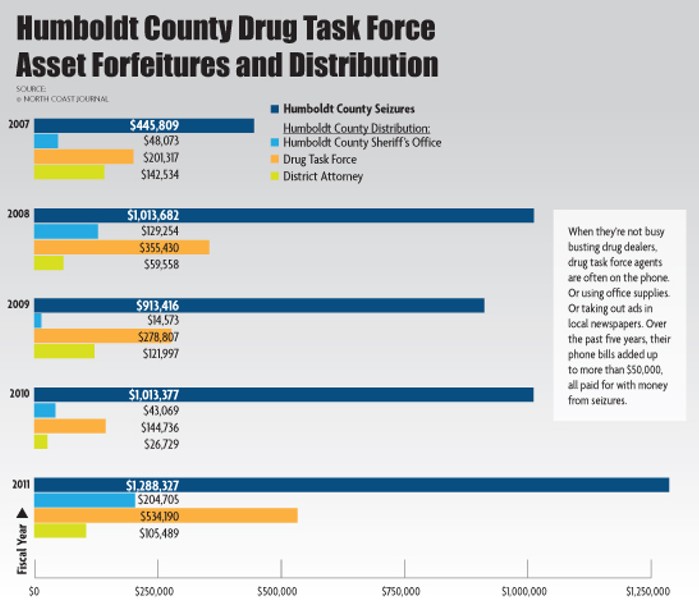

The money pours in, $1,000, $10,000, sometimes $100,000 at a time. Last year the task force seized more than $1 million from suspected criminals. It seized another $1 million the year before, and more than $900,000 the year before that. Humboldt County, population 129,000, seizes on average at least a dozen times more money per capita than California does as a whole, according to state Department of Justice data. Roughly two-thirds of that money ends up in the coffers of law enforcement agencies and offices in Humboldt County. Another portion goes to state agencies, including the Department of Justice and the Highway Patrol. Last year the Humboldt County Sheriff's Office took home $200,000, the district attorney's office got $100,000, and the drug task force got $500,000.

The drug task force is a special investigative anti-drug unit made up of nine or 10 agents borrowed from the sheriff, the district attorney, the Highway Patrol, and the Eureka and Arcata police departments. The contributing parties pay their respective agents' salaries and overtime, and provide their weapons and equipment. As of Jan. 1, the task force became county-run. Budget cuts forced the California Department of Justice to end its longtime partnership with the unit, for which it had previously provided funding and a commanding officer. Humboldt County had to choose either to do without its specialty drug-busting team, or to take it over. The task force's local executive board picked the latter. Members say that little will change with the unit's day-to-day operations. It will continue to seize drugs, and the money and property that its officers believe are tied to drugs. Public records detailing how the task force has spent this seizure money over the past five years provide a window into its inner workings. The records reveal the fiscal life of a unit that travels frequently, blows through office supplies and likes to yak on the phone.

[][][]

In early September 2009, police applied for a search warrant against Kenneth McCasland, whom they suspected of cultivating marijuana for sale. A judge signed a warrant for three addresses in Arcata and one in McKinleyville. The first house, just across the bridge from Humboldt State, contained four pounds of marijuana, two scales, turkey bags, a doctor's medical marijuana recommendation, plus $2,235 in cash, according to court documents. Another house contained more than 100 marijuana clones, 1,200 stalks with drying buds, more processed marijuana, hash, a garbage bag full of trim, two more doctor's recommendations, and $22,000. McCasland was arrested at the scene. It would be a good day for any cop, but the best was still to come. Following the raids, a judge issued the drug task force another warrant, this time for McCasland's bank accounts. The five accounts -- one with Wells Fargo, three with U.S. Bank, and one with Bank of America -- held more than $100,000. The task force suspected that the money was the proceeds from drug sales, and so seized it.

McCasland was sentenced to one year in jail, plus three years of probation. His money first went into Special District Account 3922, the county's holding account for seizures. From there it was divvied up, along with all the other seizures from that year. A small portion went to the nonprofit California District Attorneys Association, and some went to the California Department of Justice. Some went into Accounts 3642 and 3921, the sheriff's and the district attorney's seizure accounts. Some of it made it full circle, back to the Drug Task Force's seizures account, number 3644.

It's not just a slush fund. State and federal laws stipulate how money from seizures can be spent. No salaries. No overtime. No guns. No bullets. No pepper spray or Tasers. No body armor. No food, no alcohol, no beverages of any kind. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the rules are intended to keep law enforcement from giving the public the impression that the seized funds are being spent frivolously.

Over the past five years, the task force spent more than $1.5 million in seized funds. It bought nearly $30,000 worth of office supplies. Its members talked their way to $50,000 in phone bills. They spent $12,900 on storage units. They burned $6,430-worth of gasoline, and they dropped $5,403 at the print shop. They took out nearly $30,000 in advertisements in the Eureka Times-Standard and the Humboldt Beacon. They called a locksmith and a tow company a couple times each, made a few Costco runs, and bought some tires at the tire store. One of the most frequent payments was to Crystal Springs. So much for the "no beverages" rule. The task force sent the bottled water company roughly 170 checks since 2007, mostly in $6.75 increments, for five-gallon refills. The drug task force office doesn't have good water, said Sgt. Wayne Hanson, the interim task force commander. "It's safety equipment," he said. "We have to keep our task force agents hydrated."

Then there are the hotel rooms. Lots of them. The big outing to Anaheim was by no means unique, although it was probably one of the most expensive. Money from the seizures account paid for rooms in the Lake Tahoe Embassy Suites, for Campaign Against Marijuana Planting training and planning seminars in 2006 and 2008. It paid for rooms in the San Francisco Hilton, where agents attended a California Homicide Investigators' Association conference. It paid for rooms at the Manchester Grand Hyatt in San Diego, where agents attended another California Narcotic Officers' Association training conference. A graphic on the brochure shows a boat sailing between two palm trees.

The task force also paid for rooms in Santa Rosa, Roseville, Palm Desert and Red Bluff; rooms in Reno, Nev., Yakima, Wash., and Washington DC. It also paid for a couple nights locally at the Red Lion and the Humboldt Bay Inn, plus a night at Blue Lake Casino. Since 2007, it has spent more than $40,000 from its seizures account on hotel rooms.

"That's training and conferences," says Hanson. He's sitting behind a conference table deep inside the sheriff's criminal investigation office on the first floor of the courthouse -- a spot he picked in order to keep secret the location of the drug task force offices. Task force agents are like schoolteachers, he explains in a deep, gravelly voice. They have to constantly train and learn new techniques, and they often travel to do so. Hanson says that when agents are on the road, they usually bunk two to a room, although he admitted that might not have been the case in Anaheim. "I was not in attendance," he says.

Hanson doesn't really look like a cop. He's wearing a navy Carhartt coat over a pea-green flannel shirt, with jeans and tennis shoes. His gray hair is cropped short, but his face is unshaven. Reading glasses hang from his collar. The casual Friday look is his normal attire, he says. When asked for a photograph, he frowns a little, then chuckles, seemingly amused at the stupidity of the question. Surveillance is one of the key duties of the task force, he says. It wouldn't do to have people knowing what he looks like. He stands up and lifts his jacket. The flannel has a badge pinned to it, and he's wearing a gun

[][][]

Cops won't seize anything unless they feel certain that the property can be tied to criminal activity, said Hanson. Once they take money or property, they serve the person with documentation of what was seized. They also take out newspaper advertisements to announce the seizure, just in case a reader sees it and thinks that the property that was seized actually belongs to him or her, not the person listed in the ad.

If nobody challenges the seizure within 30 days, then it's over. Simple as that, the money belongs to the government. Most people don't fight the seizures, said Hanson. If they do, and the amount was less than $25,000, then it's up to the district attorney to prove in court that the money was tied to illegal activity. If it's more than $25,000, then the burden of proof is on the property owner. The rationale behind the division is that if someone is walking around with more than $25,000 then they should be able to quickly say where it came from. District Attorney Paul Gallegos said that it's usually pretty clear whether the cash was legitimately earned. Prosecutors look at work history, land ownership and expense records to get a feel for whether someone makes their money legally or not.

Seized asset cases are tried as civil proceedings. That means that the money or property itself is on trial, which leads to odd-sounding case names like "County of Humboldt vs. $67,201.20," or "People vs. John Deere Tractor." Sometimes these cases are connected to criminal trials, as in McCasland's situation. When that happens, the civil case is put on hold until the criminal trial resolves.

When defendants plead guilty, the seized property is frequently part of the resolution, said local defense attorney Jeff Schwartz. Most marijuana cases involve seized assets, he said. Defendants will often sign away their ownership of the property in order to move the case forward. "It's inevitably part of the plea bargain," Schwartz said.

Even if the suspect is acquitted, their money isn't necessarily free to go. Unlike a criminal conviction, when the defendant must be found guilty beyond all reasonable doubt, in a civil case there must simply be a preponderance of evidence -- that is, 51 percent of the evidence points towards guilt. If prosecutors can show that the majority of the evidence points to guilt, then they win.

Sometimes, however, the civil cases aren't tied to a criminal case, meaning that the cops took money or property without charging any person with a crime. That raises the ire of defense attorneys and civil rights advocates, who say that it violates both the property owner's right to privacy and the presumption of innocence. These administrative forfeitures, as they're known, aren't uncommon locally, said Schwartz, although neither he nor Gallegos could give any solid estimate of how often it happens.

It does happen, albeit very rarely, that someone gets some or all of their property back after police took it. That doesn't mean that the task force is seizing money from innocent people, said Gallegos. It can just mean that prosecutors weren't able to untangle the legal earnings from the illegal ones, and made a deal to return a portion of the money to the defendant. In five years, out of the hundreds of seizures, the county has only cut 20 or so checks to return money to suspects. The two recipients who the Journal reached by phone both declined to comment, saying that they had put that time in their lives behind them.

[][][]

A note from the Plaza Shoe Shop in Arcata arrived in the drug task force's Post Office box last March. The boots are ready, it said. Months earlier, six officers each picked out a pair of White's boots at the shoe store. Employees drew outlines of their feet, took measurements of their arches and heels, and measured the circumference of their legs at two-inch intervals. Based on those measurements, workers at the White's factory in Spokane, Wash., hand-stitched the leather boots together. It's the custom fit combined with the hand-craftsmanship that makes these work boots the most comfortable and durable on the market, proclaims the White's website. Those fancy trimmings don't come cheap. Former task force members Dan Harward, Ryan Maki, Chris Ortega and Jack Nelson all got pairs that cost $396 each. Cyrus Silva ordered special heel inserts, and his pair cost $424. Mark Peterson's pair is insulated, and cost $515. With tax, the total for the boots came to $2,750.The boots, Hanson explained, are safety equipment, and as such, are a justifiable use of seizure funds. They're intended to protect agents' feet and ankles when they're doing busts on the steep Humboldt hills. White's are the best, said Sgt. Hanson. He pulled out a pair of his own and set them on the conference table. They're brand new, still unlaced -- matte black perfection, with not a scuff. They look like real stompers, with thick leather sides and deeply grooved treads.

None of the people who got the boots are currently on the task force, Hanson said. Some of them weren't even on the force at the time of the purchase. Hanson said they got boots so that they would be ready if they were needed to help out with a bust. The agents who were on the force have since rotated back to their respective agencies.

Daniel Harward, the agent supplied by the state Justice Department to command the task force, approved the charges, as did its executive board.

[][][]

Members of the drug task force executive board say that money from seizures is nothing but a byproduct, an afterthought really, of the task force's real mission of intercepting drugs.

When the word came that the California DOJ was pulling its support for the task force, Sheriff Michael Downey said that he immediately suggested that Humboldt County take over full responsibility for the unit. His fellow executive board members -- Gallegos, Eureka Police interim-Chief Murl Harpham, Arcata Police Chief Tom Chapman, and CHP Capt. Harry Linschoten -- agreed unanimously. The money from forfeitures did not come into the discussion, he said. The real benefit of the drug task force, Downey said, is its effectiveness in fighting drug-related crime. In fact, he said, last year the task force was awarded first prize for "Most Effective Drug Interdiction Team in the Nation" by the SKYNARC International Narcotics Interdiction Association. There may have been other drug task forces that seized more drugs, Downey said, but no other unit compared per capita.

That effectiveness, the board decided, was worth shouldering the extra costs that the California DOJ used to pay. The state provided a commanding officer and office space, which together are costing the task force roughly $120,000 to $140,000 annually to replace. "We could have just let this thing dissolve and go away, but we recognize its importance," said Downey. "This has been such a successful task force." Because the task force is equipped to do the surveillance and research required during investigations into large-scale drug manufacturing and cultivation, Gallegos said, it is the most effective tool for fighting Humboldt County's biggest problem. The sheriff's office will be taking the lead on the unit, and will supply the new task force commander. The executive board is still working on a new memorandum of understanding to outline the task forces goals and responsibilities, but Downey said that he hopes to see no changes in how the task force is run. As far as he knows, the rules on what the money can be spent on will remain the same, he said.

He and others dismiss any suggestion that this is this policing for profit, or that the new boots and hotel rooms have anything to do with the task force's stunning success at seizing suspected criminals' money.

Yet asset forfeiture's more ardent opponents see the practice as little more than thinly-veiled robbery by the police.

The pure volume of money involved in civil forfeitures means that some crookedness is inevitable, said Brenda Grantland, a lawyer affiliated with FEAR.org, an anti-forfeiture organization. There is a place for forfeiture, Grantland said, but it should be criminal forfeiture, where prosecutors must get a criminal conviction in order to keep the money. "If someone has made millions of dollars doing something illegal, that money should be confiscated, I agree with that," she said. The problem with civil forfeiture, she said, is that it gives law enforcement motivation to go after people solely for their money. Any victims of the property owner should get the first cut, she said, but that it rarely happens. "It's become a very corrupt thing," Grantland said.

In Humboldt County, defense attorney Schwartz said, "I'm sure there's a big sigh, when they go on a big bust and find no money. I'm sure they're not thrilled about it." He doesn't, however, think that seizing funds is a major motivator behind drug busts.

Gallegos said that when he can, he uses the seized money to benefit the community. His office recently spent money from its seizures account to buy new video cameras for Eureka police patrol cars. Still, he said that he recognizes that there is always some danger in allowing law enforcement to spend the same money that it seizes. "I understand the corrupting power of money," he said. "You try to be responsible. We don't want to get in the position where they're drug dealers, but we're thieves."

[][][][]

Sgt. Hanson wasn't at the bust in Hydesville last fall, but he could picture it. There would have been a lot of cops. "We always flood the area with as many officers as possible," he said. "Overwhelming force." It would have been in the early morning, he said, when people are usually still sleeping, groggy, disoriented. It would have been loud, with officers yelling at the people in the rooms, pointing guns at them, telling them to get down on the ground and put their hands on their heads or behind their backs.

The scene doesn't hold any thrills for him. Clad in body armor, gun drawn, standing outside the suspect's door -- he's been there countless times. "Let me put it this way," he said, with the barest hint of a smile. He held up his wrist. "If my heartbeat right now is at 60, it would be 60 there."

The swarm of officers, yelling and waving their guns but internally calm, arrested property owner Stanislaw Kopiej and three others at the scene. During their search of the property they found 400 pounds of dried marijuana, 400 growing marijuana plants, and six guns. Inside the chicken coop they discovered a white, square plastic bucket. Maybe their hearts thrilled, just a little, when they opened it. Cash. Stacks of $20s. The drug task force counted the money -- $175,000 -- and seized it.

This fall the California Narcotic Officers' Association's 48th annual training conference will be held at the Anaheim Hilton. Officers will choose six four-hour workshops, and there will be special events in the evenings. This year, though, there will be no entertainment on the third night. Organizers are encouraging attendees to use that night to explore the area, to walk the palm-lined boulevards with their families, and watch the fireworks over Disneyland.

Comments (38)

Showing 1-25 of 38