On a half-overcast day in early spring, environmental scientists Scott Bauer and Gordon Leppig get into a big, white, double-cab pickup with the California Department of Fish and Game logo on its door. Bauer starts the engine and steers the truck out of the parking lot of the DFG's Eureka offices in Old Town, and picks a path away from the waterfront.

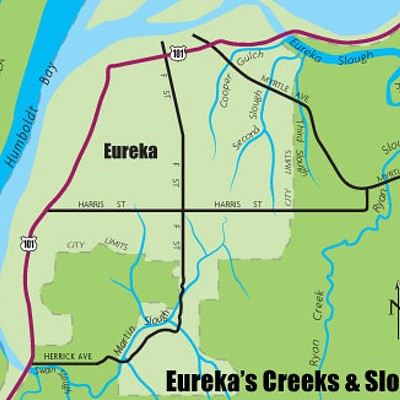

The truck turns onto Myrtle Avenue, which rises and dips as it crosses several major gulches that thread through the city. Bauer slows at the first dip and points off to the right — southwest — into a deep, broad, mysterious thicket of trees and brush, shadows and light, nudged by a tame stretch of city park.

"That's Cooper Gulch, that line of trees," says Bauer. "To me, it's pretty obvious that Cooper was moved over when they built the ball fields. Around the turn of the century they just moved the creek over."

"They want to put a building right there," says Leppig, pointing to a cleared area not far from the gulch. Bauer drives out of the dip, then down another. At a strip of grass next to the Tea Garden cafe, he pulls over and parks.

"This is actually a city park right here," Bauer says of the unmarked grassy strip, then points at the field beyond it that leads into a thicket where, somewhere, a creeks flows. "This is Second Slough, and it's got coastal cutthroat trout. If you look at the old aerial photos, you can see this was pasture. See the old fence down there? They probably drained the creek to create the pasture. Now it's gone feral, riparian. It's recovering."

"It's got nice brackish water," adds Leppig. "There's leakage from the tidal gate."

"We hope some day to make [the tidal gate] more fish friendly," says Bauer. "It'd be great coho habitat."

Driving again, Bauer takes a side road and stops next to a ravaged wetland. Half of it has been filled in over the decades by people dumping unwanted dirt; the other half's recently been partially cleared, its trees cut to the ground. Houses and condos border it on high banks. A stream bends around the cleared area and into an untouched spot where birds — Wilson's warblers, perhaps — sing in the remaining red alder and Hooker's willows. The sound of a siren on Myrtle Avenue punctuates the spring-like lull.

"This is a classic example of what's going on in Eureka's greenways and gulches," says Leppig.

Back in the truck, they talk about city things. Pavement. Rooftops. Raingutters. Septic systems. Cats — hey, they eat songbirds. Discarded pills. Chemicals. Lawns.

And then they go back to the fish. Throughout this urban landscape the Fish and Game truck is traversing, little streams that sometimes look like no-consequence ditches are flowing through subdivisions and squeezing under roads before feeding into the sloughs that connect to Humboldt Bay. And up some of these little streams and into the tiny ditches are swimming young coho, cutthroat, steelhead and other fish. A century ago, says Leppig, all the streams and sloughs would have been connected and likely stuffed with thriving fish.

Fish and Game, he says, would like to see a return to those fish-full days. As much as feasible — after all, town's here to stay. It's growing. Still, it's Fish and Game's job, as state trustee of fish and wildlife, to improve and maintain their habitats — urban or otherwise, and whether or not the critters are in them at the moment.

You might say Fish and Game's a little bit Johnny-come-lately to the urban scene. Heck, Leppig says it. "Fish and Game — and we own this, we're fully aware of it — has not been paying attention to the cities and the county like we should."

Now they are. And planners everywhere in the region are keenly aware of it.

It is an odd sight,this huge Fish and Game truck roaming city streets, past shopping centers and doctors' offices and rows of comely houses. It's the sort of rig one would expect to see up in the forests, negotiating rough logging roads and whining in low up steep grades.

That was pretty much the case up until a couple of years ago, says Leppig. On an afternoon in mid-March, Leppig is sitting in his office in the faux-Victorian building that's part of the Northern Region DFG's Eureka office complex in Old Town. Stacks of reports hold down a table and desk. One wall has a plant poster on it. On another, an African reedbuck's head stares solemnly toward the window through which you can see the fishing boats at Woodley Island Marina. On the white board below the reedbuck Leppig has written in blue ink, "Vox veritas vita!"

"Make your life speak in truth," translates Leppig.

Before 2006, he says, the majority of the Northern Region DFG's habitat conservation staff in Eureka was devoted to helping timber companies develop habitat conservation plans to protect plants, streams and wildlife from logging impacts. A guy based in Redding handled applications from the entire region north of Sacramento for "lake and streambed alteration agreements" (LSAAs), which are required to put in a culvert, build a bridge or anything else that might impact a water body.

"Everybody here worked in timber," Leppig says, adding he spent six years on Pacific Lumber Co.'s habitat conservation plan. "Well, what we realized was, the streams get an awful lot of protection up in the woods. But as soon as the streams leave the timberland and enter the city of Eureka, or the county, or the city of Fortuna, we are not giving them the amount of time and attention that they deserve. And in fact, it doesn't make a lot of sense to protect headwaters streams or major rivers when they're up on timberlands if as soon as they come down [into town] we've turned a blind eye."

So two years ago, at the urging of field staff, the DFG devoted a staff of 12 to working in the urban coastal environment. Bauer was hired to do the LSAA reviews for Del Norte and Humboldt counties. Leppig pores over city and county general plans and, with another scientist, reviews proposed urban development projects in Del Norte and Humboldt counties to ensure that they comply with the California Environmental Quality Act.

Leppig picks up a copy of the CEQA rules, a yellow book whose pages have been marked with dozens of multi-colored tabs, thumbs to a well-worn spot and reads aloud a passage.

"It's great," he says. "It's like quoting Scripture."

California, says Leppig, has the most robust environmental laws in the country. "The gist of CEQA is, for any one project, the project needs to lay out any potential significant environmental effects," he says. And it has to mitigate them — by avoiding the impact in the first place, or restoring the habitat, or other actions.

Leppig's team is focused on avoiding the impact. But the DFG can't tell someone they can't do a project — it can only advise. If a project might hurt a critter or its habitat, the proponent has to consult with the DFG because it is the state-appointed trustee of fish, wildlife and their habitats. But even with a beefed-up team, Fish and Game doesn't have time to review every project.

Leppig believes there's a better way to tackle habitat conservation than reviewing things project by project. And he sees a perfect mechanism in the county's and the cities' general plans, many of which are undergoing their 20- to 25-year updates right now. Humboldt County is wrapping up its General Plan Update, as is the City of Fortuna. Trinidad — a city entirely on septic systems — is just getting started. And the City of Eureka, though its last update was just 10 years ago, is about to release the draft of a related document near and dear to Leppig's heart: the long-awaited Greenways and Gulches Ordinance.

"This is a golden opportunity for the county and for the cities to evaluate how growth and development will impact trust resources," Leppig says. "Environmental regulations have changed, species have been listed, threats have increased. And so as development continues and the county grows and prospers, the impacts change over time. For instance, this was a big deal: Coho salmon was listed by the state in 2004. So here's a critter that's declined by 70 percent since the 1940s."

What Fish and Game would like to see is a comprehensive approach to conservation in these plans — "regulatory certainty," Leppig calls it, standards that all developers can follow to minimize impacts to natural resources. In particular, he'd like to see the county and cities require wider buffer zones around urban streams and wetland areas and to make developers control stormwater runoff so it doesn't erode streambanks (and blast out young salmonids) with high peak velocities or carry contaminants into sensitive habitats.

The California Forest Practice Rules force timber companies to leave 150-foot buffers on either side of anadromous fish-bearing streams from the edge of the riparian area. "And you can't have any heavy equipment in it, and it's essentially a no-cut buffer," says Leppig. "For the first 75 feet you have to leave 85 percent of the canopy. And for the next 75 you have to leave 65 percent."

But once that stream leaves timberland, governed by the California Department of Forestry, and enters county or city jurisdictions, the buffers vary in size but, in general, are much smaller. In Fortuna, for instance, the stream would get a 25-foot buffer from the centerline of the creek. "And if the stream's 15 feet wide, that's no buffer," he says. Why, a 30-foot-span alder wouldn't even fit into it.

In Eureka, outside the coastal zone, the stream would get a 100-foot buffer if it's also outside the "urban development and expansion area," says Leppig, and a 50-foot buffer in the built-out urban areas.

In McKinleyville, in the county, whose 2002 community plan is considered state-of-the-art says Leppig, developers can pave 25 percent of their buffer zones and also put in a septic system.

"Well, if you put in a septic system, and you remove riparian vegetation, you can't have willows and alders and trees growing in the leach field," says Leppig. "You basically have a lawn. And then you have water quality issues. How is that helping the quality of a wetland, having a septic system right next to it?"

And even Arcata, the champion of wetland restoration, only requires 25-foot buffers in town.

Once the stream flows into the coastal zone, governed by the coastal commission, the buffers widen again, to 100 feet.

Leppig says CDF and the coastal commission require bigger buffers for good reason.

"It's not just what's in the water," he says. "Riparian areas are really important. Streams need trees. They need them to provide nutrients, they need root systems to provide bank stability, they provide habitat for birds, for mammals, for critters. And shade — salmonids need clean, cold water. And almost all salamanders — amphibians are declining world-wide, now — they're born in the water, and they spend their adult lives in the upland. So if all we do is protect a wetland, and we don't protect the forestland and the riparian area around the wetland, then we're losing habitat function on many levels."

Leppig says he reads lots of reports that support these ideas. One, published in the journalEnvironmental Science and Technology last year, is of a study by Oregon State University researchers who found that dissolved copper impairs a coho salmon's sense of smell and thus its ability to detect predators. Copper from vehicle exhaust and brake pads gets deposited on roads and parking areas and can be washed into salmon-bearing streams and estuaries by stormwater.

Another report, from 1990, by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, notes that between the 1780s and 1980s, the lower 48 states lost 53 percent of their original 221 million acres of wetlands. California lost the most, 91 percent.

"Locally," says Leppig, "Humboldt Bay has lost greater than 90 percent of its former marsh habitat."

Leppig slaps a four-page document on the table: "State of the Industry Report 2007 — Fisheries," prepared by North Coast Prosperity. It hails the coming new age of Humboldt Bay's commercial fishery: a new fisherman's terminal with dock, jib cranes, work space and the potential to provide 25 to 50 new jobs. It discusses the ups and downs of crab, tuna, salmon, crab and oyster production. Leppig walks to the window and looks out at the marina and the north end of the bay.

"That's the second largest estuary in the state of California," he says. "We have the largest eelgrass beds in the state. It's the largest producer of oysters in the state. We've got 120 species of fish in the bay. Freshwater Slough — Eureka Slough — has 28 species of fish, and lots of listed species. So the bay is a biodiversity hotspot. Including green sturgeon, which is pretty amazing. These streams are chock-filled with state and federal listed species — threatened, endangered, rare. They're vitally important economically to commercial fisheries — there's our fleet — and to recreational and sport fishing, and to our way of life. This is our national heritage, it's our regional heritage, it's our cultural heritage. So, we feel like we could do a better job of protecting these resources."

He's been working hard to get out that message. "I've made presentations to the Arcata Planning Commission, the Eureka Planning Commission, the Fortuna staff, Danco, Winzler and Kelly, SHN, the City of Blue Lake, the Association of Home Builders...."

And he's written letters. Long, exhaustive, sometimes damning letters.

On July 17, 2007, Leppig sent a 27-page letter (signed by regional manager Gary Stacey) to Michael Wheeler, a senior planner with the Humboldt County Community Development Services, commenting on the county's notice of preparation of a draft environmental impact report on the General Plan Update.

The letter says the DFG supports "Sketch Plan A" in the draft EIR "because it focuses future growth and development into areas where there is existing infrastructure ...." It commends the county for committing to developing standards and ordinances for enforcing the update's policies. But it says that the county's plan doesn't go far enough.

It notes that two of California's three largest river systems flow through the county, and that they and other streams and estuaries support a couple dozen state and federally protected species, including coho and Chinook salmon, steelhead, coastal cutthroat trout, green sturgeon, tidewater goby and the willow flycatcher (a bird). It also notes that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has listed as sediment-impaired most of the county's big water bodies — Humboldt Bay, Freshwater, Jacoby and Redwood creeks, and the Eel, Elk, Klamath, Mad, Mattole, Trinity and Van Duzen rivers.

It also notes the county's projections that by 2025 its population will have grown by 16,000 people, and that to meet that growth it will need 274 more acres of commercial/industrial lands and 6,000 more housing units, and that water demand will increase from 30 million gallons a day to 49 mgd.

The DFG letter makes 29 recommendations. Among them, it wants the county to develop a county-wide LSAA — "given," writes Leppig, "the County maintains more than 1,500 miles of roads, 100 bridges and three levee systems, and the frequency in which the County requests LSAAs." It also suggests a county-wide habitat conservation plan. It wants the county to make developers install detention basins, percolation systems, grassy swales and other low-impact-design elements to soak up stormwater runoff; mandate wider, no-disturbance riparian buffers; require shielded street and exterior lighting; hire a biologist to work on project reviews; and more.

On Aug. 10, 2007, Leppig sent a 12-page letter to the City of Fortuna's planner Liz Shorey. It too, outlines the resources at stake, noting as well the city's growth projections: by the year 2030, 6,000 more people, 2,800 more housing units, one million more square feet of retail and industrial space, and, in two of the update's alternatives, the conversion of agricultural lands for industrial use on Rohnerville Bluffs.

But the DFG's assessment of Fortuna's update is punishing:

On page three of the letter, under the heading "riparian habitat protection," the letter states: "While the Policy Document contains much positive language regarding protection and enhancement of Fortuna's streams, DFG finds it and related Update reports include few enforceable standards or ordinances to minimize and mitigate the impacts of future development to these streams."

The letter notes with dismay the city's 25-foot buffers for coho-bearing streams, then recommends 150-foot no-disturbance buffers on the Eel and Van Duzen rivers, 100-foot buffers on smaller fish-bearing tributaries like Strongs Creek, and 50-foot buffers on non-fish-bearing streams.

"Without effective riparian buffers," says the letter, "...the City is likely to undertake or permit projects pursuant to CEQA that may result in the incidental take of listed salmonids ... [that] would result from increased water temperatures, loss and degradation of habitat, non-point source pollution inputs, and altered hydrology." And that, says the letter, could result in cumulative impacts — in CEQA-speak, that means every time a project comes up, in the future, it could require a time- and money-sucking EIR.

The letter lists a number of other recommendations similar to those presented to the county. An attached memo outlines findings from the "DFG Coastal Watershed Planning and Assessment Program 2006 Lower Eel River Basin Assessment." It's a litany of ills: impervious surfaces, undersized culverts, stream disturbances, unrestricted livestock grazing, more winter floods, sewer overflows, too-high flows, too-low flows, a flooded wastewater treatment plant, sedimentation in creeks.

On Aug. 27, Leppig met with Fortuna city staff. And then, on Oct. 31, he sent a 14-page letter to Fortuna City Manager Duane Rigge. Leppig calls that letter "nuclear." A city staffer called it "vigorous."

"This letter," it says, "serves to inform the City that DFG finds the City's current efforts, as a lead agency pursuant to CEQA, are inadequate to mitigate the impacts of projects on wetland and riparian habitats and to protect and maintain listed salmonid fish populations and avoid their incidental take."

The letter reiterates the points of the first letter. It notes that, at the Aug. 27 meeting, the city said it would not include Fish and Game's recommendations in its updated general plan.

Then the letter pulls out the guns. "It has come to the DFG's attention that the City has not been following the procedural requirements of CEQA to submit certain environmental documents to the State Clearinghouse within the Governor's Office of Planning and Research. ... DFG is aware of a number of recent City-approved projects that were not sent [to the Clearinghouse] despite being located directly adjacent to sensitive habitat and potentially impacting State fish and wildlife resources. A query of the CEQAnet Database on the OPR website shows the City has sent four documents to the State Clearinghouse in 10 years."

The letter then mentions a specific troubling project: the Strongs Creek Residential Subdivision, approved by the city on Aug. 6, 2007, with a mitigated negative declaration saying the 63 residential lots on 14.5 acres would not have a significant effect on the environment. It incorporates none of the DFG's notions of stream protections. And, the developer bypassed some key regulations.

"That's an ugly and messy case," says Leppig, back in his office. "There's a cease-and-desist order from the Army Corps of Engineers. There's a stop-worker order from the regional water quality board. The developer filled in a wetland and altered a stream."

Leppig says that case just underscores the DFG's desire for stronger protections in these general plans. "In that Oct. 29 letter to [City Manager] Duane Rigge, we laid out the options," he says. "We said, in light of the whole record of everything that's been done before, everything that's in the project pipeline right now and everything that we can anticipate in the future, cumulatively this is going to have a significant effect on the environment — you've gotta do an EIR. And, they're not doing developers and property owners a service, setting them up to have to do an EIR every time they want to do a minor subdivision or a lot-line adjustment or to build a second unit."

He thinks that, with the DFG recommendations in place, future developments would be far less likely to trigger an EIR.

So how are the cities and the county responding to this flood of advice from the DFG?

"We have gotten a lot of feedback from planners, from developers, from the consulting industry — they have been thrilled that Fish and Game is back in the saddle," Leppig said in another interview last week.

Wheeler, the county planner, said last week that despite the fact that the DFG's 27-page letter with the 29 recommendations was submitted eight to nine months after the closing of the comment period for the Notice of Preparation of a draft EIR on the general plan, he sent the comments to the staff and consultants still working on various elements in the plan. Wheeler didn't say much about the comments, except to say he didn't think a one-size-fits-all buffer system would work. And, as for the suggestion that the county hire a biologist, he said, "The county relies on Fish and Game to be our biologist."

Rob Wall, a planner for the City of Eureka who's been working on its greenways and gulches ordinance — in the making since 2002, and an element noted in the 1997 general plan update — says he's glad the DFG is taking a hard look at urban planning.

"They're actually sending over a critique of my latest draft," he said last week. "It's nice to be able to pick up the phone and get an answer right away. I think the only friction — and I think it's unintended on their part — is the 11th hour in which Fish and Game has come in. It's like, ‚ÄòWhere were you?'"

City of Eureka Manager Kevin Hamblin said he and his staff recently met with Fish and Game on the greenways and gulches ordinance — which was ready to go several months ago, until Fish and Game stepped in. That's delayed things until at least April, when Fish and Game will submit written comments. At their meeting, Hamblin said, Leppig asked the City to change the riparian buffers from 50 feet to 100 feet in the new ordinance. "We said, ‚ÄòThank you for that information.'"

But, he added, he too is glad to have the DFG on board. "Welcome to the party."

Meanwhile, Fortuna City Manager Duane Rigge relayed a "No comment" through a city staffer when the Journal called last week to ask how things were going with Fish and Game. Later, however, Rigge did offer a reply by e-mail. In it, he noted that the City of Fortuna's been working on its General Plan Update for more than two years, and has held workshops and has received public comments — all of which were broadcast on Channel 10 TV. He said the draft Program EIR is about to be circulated for its 45-day review.

As for Fish and Game, he wrote: "I have offered on several occasions to schedule a business item on the City Council meeting agenda in order to provide time to DFG staff to address the City Council. The offer has never been accepted. I have also offered to schedule a special time during the Public Hearing process for the P-EIR to allow Fish and Game an opportunity to address the City Council and Planning Commission. Again, the offer has not been accepted."

Leppig said last week that Fish and Game tried this winter to schedule a meeting with policy staff, Mayor John Campbell and a planning commissioner to talk about the issues raised in his agency's letters. "But the City determined that was infeasible," he said. But, he said, Fish and Game would welcome time set aside for it during the public hearing process.

"I think it would be great to develop a good working relationship with them," said Leppig. "We have a long way to go. So, we're starting that now."

Leppig says he's aware that it might be startling folks to have Fish and Game suddenly come out the woods waving vigorously.

"The important thing is, we're not trying to stop development," Leppig said. "It's a matter of how do we grow and develop and prosper and still maintain our fisheries and our creeks and our wetlands?"

The Fish and Game truck rumbles along more Eureka streets then passes, imperceptibly, into the county. Scott Bauer stop the truck on Hill Avenue, near the hospital. The smell of cooked beef wafts warmly over from the Stars burger shop on Harrison. A clump of thick-stemmed horsetail, a wetland plant, pokes up out of the ground by the pavement. Bauer and Gordon Leppig walk out onto a grassy bench of land between houses to gaze down into Third Slough — wild, thick with trees. Bauer discovers deer pellets on the grass; Leppig points to a non-native holly. Someone wants to build a couple more houses on this bench, Bauer says, but the developer has worked with Fish and Game staff so the project should be OK.

Past developments here have slipped under the DFG's radar. Nearby, someone buried a steep tributary to Third Slough by dumping dirt in it anchored by an iron-staked retaining wall. Further south, someone else scraped a huge patch of natural growth out of the bottom of the gulch and built a house with a stately lawn and a smooth concrete driveway whose tilt toward the slough can easily transport rainwater and whatever else into the stream.

Back in the truck, Bauer picks a crooked path across Henderson Center into another urban maze where more slough tributaries poke their fingers into the neighborhoods. More problems: a house on stilts overhanging a stream; a redwood-bordered stream, tributary to Martin Slough, traveling unmolested through a meadow of bright green skunk cabbage showing fat yellow blooms, until it gets piped under the road for a dozen yards; the same stream emerging into another wet meadow where a perpetually soggy old yellow house wallows; a road, soon to be widened, swimming through a watery field that's raucous with frog song on summer evenings.

And then they're at the Eureka Municipal Golf Course, through which Martin Slough winds lazily. It was here in 2006 that biologists caught, much to their surprise, 144 juvenile coho salmon over-wintering in the 17th hole pond. Southeast of here, says Leppig, in a region whose forested ridges and gullies drain to Martin Slough, the county predicts growth of up to 7,000 more housing units.

"If we want to bring the salmon back, it's not just about the Klamath dams, necessarily," Leppig says. "We have fish in our own backyard. And Grandpa and Grandma and the kids can go out the back door and catch 'em and bring 'em home to barbecue. Only, they cannot do that right now. But they could."

Someday. Maybe.

Comments