H umboldt County is a “natural” sort of place. And we’re not just talking forests, rivers, seashores and mountains — when it comes to food, we’re ahead of the curve on the suddenly hip natural trend. We have fruit and vegetable farmers who have been completely organic for decades, dairies and cattle ranchers producing grass-fed beef and organic milk, and a cadre of shoppers who have grown used to stores that stray far from conventional fare.

While many in the rest of the country are just now tuning into the benefits of natural foods through the rapid growth of chains like Whole Foods Market, we have stores like the Co-op, Eureka Natural Foods and Wildberries that have been serving us for years — decades, in fact. Even neighborhood markets like Murphy’s have long-established ties with local growers and offer natural and organic products.

Meanwhile, up the road in McKinleyville, a national grocery chain is making its bid for its share of that natural market by revamping its look and adding organics to its product line. A recent “grand reopening” heralded a transformation of sorts.

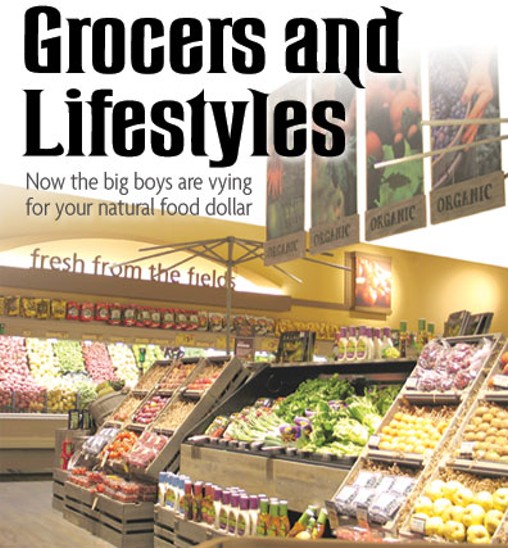

As soon as you walk in the door you know it’s not your same old neighborhood Safeway. A riot of color from an island of flowers greets you. Next to it a display of artfully arranged fruit — nectarines and grapes in wooden boxes, shining apples in wooden barrels — suggest an old country store. Straight ahead a sign reading, “Safeway — ingredients for life,” hangs above a cold case full of packaged salad greens, many of them marked with an “O” for organic.

The reworked produce section just inside the door shows the most dramatic change. Faux wood floors have replaced the linoleum. More wooden cases stacked with decorative fruit and vegetable arrays are illuminated by subdued spotlights, positively warm in contrast to the previous fluorescents. Banners showing the hands of what appear to be real working farmers draw you to an island of organic produce. Signage on the wall suggests that the food here is “fresh from the fields.”

The overall effect suggests that this remodeled store in McKinleyville has gone organic and natural and is now akin to stores like the Co-op and Wildberries. Not that it shares their design — in fact the new Safeway look is much more like a store from the Whole Foods chain, and intentionally so.

According to Esperanza Greenwood, a flack from Safeway’s California headquarters in Pleasanton, the refurbishing of the McKinleyville store is one step in a major transition in the works throughout the chain. “It’s more than just a paint job,” Greenwood says. “Safeway is remodeling all its stores across the country in what we call the ‘lifestyle’ format, in response to our customers’ wants and desires.” Safeway’s plan is to convert all its stores to the format by 2009.

Locally, that means more than a Whole Foods-esque produce section. More organic products are offered storewide, including Safeway’s new instore brand, O Organics, launched last year. There’s also an expanded deli, a new olive bar, a soup cart, a cheese table “with an international selection” and a “full service” bakery with cakes, “artisan” breads and bagels.

The chain-wide transformation comes in the wake of a slow decline in market share for traditional grocers over the last few years. Old-school chains that once touted bargains and relied on loyal customers used to convenient locations are discovering that the 21st century shopper is less loyal and more willing to drive to the next town, either to save a few bucks or to find some product that’s not available at the neighborhood store.

On a national level, shoppers are being pulled in two directions. On one hand, those living on tight budgets are trying to save money by shopping at places like Wal-Mart, where the motto is “Always Low Prices,” or locally, at bargain stores like WinCo, “the supermarket low price leader,” and to some extent at membership stores like Costco. At the same time, health-conscious food shoppers are striving to improve their diets — as a lifestyle choice — even when doing so may cost more.

In Safeway’s case the “Lifestyle” rebranding campaign aimed at the growing upscale natural market is an attempt at repositioning, or as the grocery trade industry puts it, “differentiation.”

Safeway Inc. is a huge chain, the second largest in North America, with 1,750 stores in the U.S. and Canada, a number that dwarfs Whole Foods Market’s 191 stores (a proposed merger with another natural foods chain, Wild Oats Markets, could add 110 stores to Whole Foods’ number). So why would Safeway care about trying to emulate Whole Foods, whose original name, Safer Way Natural Foods, was a none-too-subtle poke at the established chain? It’s hard to say, and Safeway’s upper management is not about to share their thinking (individual employees, even store managers, are not allowed to speak with the press).

An educated guess and a quick read of various supermarket trade mags says it’s a combination of two things: facing the reality that those “low prices” customers are lost to Wal-Mart (and Wal-Mart-like stores), and a jealous look at the demographics of natural foods consumers, who tend to come from higher income brackets and seem willing to spend more for what they eat. (An oft-told joke is that Whole Foods is aka “whole paycheck.”)

Wildberries president/general manager Phil Ricord figures Safeway “obviously saw a change in the demographics in McKinleyville,” and considered that in choosing the store as first in Humboldt to get the “Lifestyle” refurb.

Ricord doesn’t imagine that changes in the McKinleyville store will have much impact on his business, which he says is “doing fine.” And he’s not totally convinced that Safeway will stick with the rebranding campaign long enough to get around to the Arcata Safeway.

Ricord points to a similar change in the Arcata store in the ’90s. “They lowered the ceilings in the produce department and put in track lighting with spotlights on all the fruits and vegetables,” he says. “They added a separate natural foods section. That lasted for about a year, but they tore it all out and went back to their conventional format.”

Ricord opened his grocery store in 1994 after working for the Co-op for 15 years. He’s quick to point to the Co-op as a store that was “ahead of its time for a ‘full-size’ natural supermarket” and “one of the first — not just locally, even nationally — to recognize the change in eating habits and the importance of natural, and, later, organic foods.”

But speaking as a competitor, he feels that the Co-op has “lagged behind” in recent years, failing to recognize the interest in organic and natural foods across an increasingly wider range of shoppers. “The new Eureka Co-op is an attempt to do that,” Ricord figures. “Same with the changes at Eureka Natural Food.”

North Coast Cooperatives merchandizing manager Ron Sharp points to “what we call the core shopper, people who were really dedicated to organics and the natural lifestyle,” as the heart of the Co-op’s business.

Sharp recognizes that what Ricord says has some truth in it. The Co-op has to expand its reach to survive. That was part of the thinking that went into the expansion, first at the Arcata branch, which grew from 9,500 square feet of retail floor space to around 14,000, followed by a major leap in Eureka. The new Eureka Co-op on Fourth Street has almost five times as much sales floor as the previous store.

The look of the new store, particularly in certain departments, definitely draws on the Whole Foods aesthetic. Before explaining how and why, it might be a good point to add a bit of disclosure and with it some history.

In 1994, I was hired as assistant manager for the about-to-open WildPlatter Café, the take-out counter in Wildberries Marketplace. The job did not last long, but it eventually led to another deli job. A couple of years later I found myself employed by the North Coast Co-op as manager of the Spoons deli, a job I began right around the time the Eureka Co-op expanded from a dark, tiny space on First Street in the former Co-op warehouse to its next location at Fifth and L.

When I was with the Co-op, plans were afoot for expansion of the Arcata store, a process that involved enlarging the building and designing a number of new features for the addition, including a revamped bakery and deli.

As part of the planning process all managers were sent to visit various upscale grocery stores in the greater Bay Area, among them Food for Thought in Sebastopol (a market that was subsequently acquired by Whole Foods), two Whole Foods Markets locations in San Francisco and another in Berkeley, where the growing chain had taken over a store once occupied by the now-defunct Berkeley Co-op.

What I found most remarkable at the Whole Foods stores was the emphasis on take-out food and the then-nontraditional lighting and fruits and vegetables presentation used in the produce sections. It was pretty much the same thing you now see at a “lifestyle” Safeway, and, aside from the large deli areas, not too different from the presentation at the recently opened Eureka Co-op.

The Co-op, founded in Arcata in 1973 after evolving out of a buying club called the Humboldt Common Market, may have a long and storied history, but the roots of Eureka Natural Foods (originally known as Eureka Heath Foods) stretch back much further.

When Rick Littlefield and his wife Betty bought Eureka Health Foods in 1985, the business was already over 40 years old. Littlefield describes “the old days,” before the natural food business was born, as a time when “you had the health food nuts like [body builders] Jack LaLanne and Joe Weider who ate bizarre stuff like yogurt and granola, which no one else ate.”

Then came the nascent natural food movement of the ’70s, “with hippies selling whole grains out of bags and fruit with worms in it. It was kind of funky.” Eureka Health Food store was offering something different, a collection of dietary supplements along with what Littlefield describes as “specialty foods and odds and ends: the Loma Linda and Worthington vegetarian lines, wheat-free products, allergy-free foods, things for Seventh Day Adventists.”

Under Rick and Betty’s ownership the business grew from small health food store to medium-sized natural foods store by adding an increasingly wide range of organic products. By 1995, when Eureka Natural moved to Broadway, it was what Littlefield deems a “full service” store with 7,000 square feet of retail floor. With the recent move to the built-to-order location next door, they’ve grown by 20,000 square feet.

The struggle, says Littlefield, will be to maintain the same personal attention customers are used to. “We just want to make it the best we can, but still keep it kind of informal and local and small,” he says. “We’re working hard not to get corporatized.”

In Humboldt County, “lifestyle” Safeway is entering an already crowded market. Even leaving aside the supermarket giant’s future plans, is there room in Eureka for two large natural food stores, both on Hwy. 101 and within a mile of each other? Maybe it’s the relatively laid-back nature of the natural foods business, but neither side seems overly worried in what would seem to be a looming battle for organic-minded consumers.

Sharp says he’s talked with Littlefield about it. “We both hope to bring in customers from places like WinCo and Safeway, people who will realize that we have the most natural foods, if that’s what they’re into,” he says.

For his part, Littlefield thinks that there’s room in the market for both new stores, but he points out with just a hint of irritation that “we had our plans going before the Co-op started on theirs.”

It was actually Rob and Cherie Arkley of Security National who hatched the plan for repurposing the Fourth Street building, which had once housed the Big Loaf Bakery. And the Co-op was not their first choice for a tenant.

“I don’t think it’s a secret that they first recruited Trader Joe’s, then Wildberries,” says Littlefield. “They finally worked out a deal with the Co-op.”

No less an authority than Cherie Arkley passes along the bad news that Trader Joe’s — a store that many Humboldt residents clamor for — isn’t interested. “We will probably never see a Trader Joe’s here,” she says. Not that Security National didn’t try, offering “all kinds of gimmies and perks for coming to Eureka.” The bottom line, according to Arkley: “Our market isn’t big enough.”

Ricord confirms that Wildberries also turned the Arkleys down. “After Trader Joe’s passed, Security National came to me and asked if I wanted it,” he says. “I decided against it.” Ricord says that he felt the location, on the edge of the bad part of town, was less than ideal.

Of course, part of the idea behind dropping an upscale market into the seedy side of Old Town is to improve the neighborhood — it’s no coincidence that Security National’s proposed Marina Center development is right around the corner. And thus was hatched what might seem an unlikely alliance between a member-owned consumer cooperative and a billionaire businessman.

“It was an incredible deal,” says Sharp. “Not only were they building the building, they said they’d purchase all the equipment: refrigeration, grocery shelving and the bulk fixtures. When I tell people from other Co-ops the developer did that, they can’t believe it. It’s pretty much unheard of.”

Sharp admits that the Co-op is still working on making best use of the large space. “It’s like you have a size 12 shoe and your foot is a nine, you have to grow into it,” he says.

With the continuing growth of Whole Foods and major players like Safeway and even Wal-Mart entering the organic and natural food business, issues like “corporatization” (as Littlefield puts it) are in fact a growing concern.

“There are more and more farms being certified organic, and that’s a good thing, but it’s kind of a double-edged sword,” Sharp says. It means that “bigger players want to get into it.”

The fear is that the organic produce business will follow the pattern of agriculture as a whole, with small family farms falling by the wayside as agribusiness juggernauts dominate the marketplace. Another concern is the dilution of organic standards as powerful players with influence on public policy enter the natural food field.

Littlefield is well aware of the potential downsides, but remains optimistic about what he sees as a “shifting paradigm,” where words like “natural” and phrases like “organic free range” have become part of the public lexicon.

He’s glad that more people are adopting a lifestyle choice he made years ago. “We always wished that everybody would eat this way,” Littlefield says. “It may create some problems, but for my part I’m happy to see it.”

When is Whole Foods coming to Humboldt?

Not any time soon. Why not? The answer can be found by following a link on the Whole Foods website marked “Real Estate,” which takes you to a page aimed at those who might want to pitch a location for a new store.

It says, “If you have a retail location you think would make a good site for Whole Foods Market, Inc., please review the following guidelines carefully for consideration:

• 200,000 people or more in a 20-minute drive time

• 40,000–75,000 Square Feet

• Large number of college-educated residents

• and so on...

According to the U.S. Census site, the population of Humboldt County at the time of the 2000 count was 126,518. It’s gone up a little since, the 2006 estimate is 128,330, but 200,000 is a long way off.

Census data show that just 16.9 percent of Eureka residents age 25 years old and up hold a bachelor’s degree or higher; the state average is 26.6 percent.

Differentiation and Coca-Cola

There’s a term thrown around in supermarket trade magazines, something each chain or independent store strives for: differentiation. It’s pretty much self-explanatory: When you have many stores carrying similar product lines, the idea is to develop a niche, to demonstrate how your store is different.

For Phil Ricord, owner of Wildberries Marketplace, the niche is “people concerned with the quality of life, and convenience” — a location within easy walking of the college campus and on the way out of town for anyone driving north.

Then there’s the store’s catch phrase: “Supermarket of choice.”

“You can buy tofu and Coke in the same store, or hajiki, or even weirder stuff, if that’s what you want,” says Ricord. “Personally, I don’t see anything wrong with eating tofu and drinking Coke. Our concept is to offer both.”

Rick Littlefield of Eureka Natural Foods changed the store name from Eureka Health Foods years ago, but he still sees health as “the heart and soul of everything we do.”

And for that reason, he says, “Unlike some other stores around here, including the Co-op, we don’t have a lot of choices for people. The only thing you can get here is the best that’s available. We don’t have crossover stuff — you can’t buy Coca-Cola or anything like that.”

He tries not to come off as overly paternalistic, but there’s a suggestion that you should trust the store to know what’s good for you. “All you can get here is what we consider a high-level quality of food,” he says, “either natural or organic, all free of pesticides and humanely made. We think the quality of the product line we carry should be very high. We don’t have choices about that.”

As North Coast Cooperatives merchandising manager Ron Sharp points out, with 10,000 Co-op members it’s impossible to please everyone. “We decided long ago that being a rural store we have to have some conventional products, but we have less now than we used to,” says Sharp.

Some would like to see the store carry a wider range of foodstuffs. There’s also a faction of vegan members that would just as soon the Co-op sold less — specifically, no meat products. “There are Co-ops out there that are very restrictive in their product line,” says Sharp, mentioning a store in another state that does not offer meat products, despite the fact that 60 percent of its customers buy meat elsewhere.

The question of whether or not the Co-op should carry Coca-Cola products has been a subject for contentious debate for years, with members citing everything from the health hazards of high fructose corn syrup and GMOs to alleged human rights violations by the corporation.

At this point the Co-op has opted to carry the Coke product line, but, at least in the Eureka store, there’s also a homemade display like something you’d see at a school science fair, advising shoppers that “The North Coast Co-op Board of Directors recommends that you should learn more about this issue.” Along with “10 reasons to boycott Coca-Cola,” you’ll find pre-addressed postcards so you can, “Tell Coke what you think!”

“If people want Coke, they can make an educated choice,” says Sharp. “If they don’t want it, they don’t have to buy it.”

Comments