- NCJ Graphics

- Broadband Into Humboldt

Passing by the Shasta County town of Platina at almost 450 million miles per hour, there's no time to stop and visit its gas-and-groceries store, its solid-waste transfer station (capable of handling 25 tons a day), or its couple hundred residents, including the brothers at the nearby St. Herman of Alaska Monastery.

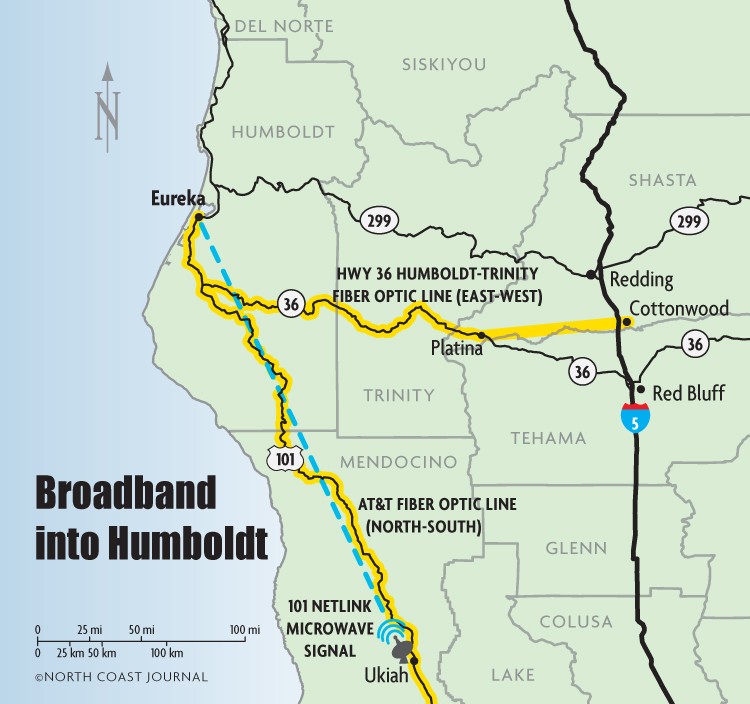

This trip of light fantastic starts about 30 miles east, in Cottonwood, between Redding and Red Bluff on Interstate 5. From there, it makes a beeline west over range and foothills toward Platina; then cruises roughly along Highway 36 before veering toward a terminus in Eureka. The 121-mile trip takes just under one thousandth of a second -- that's for a bit of a megabyte pulsing at about two-thirds of the speed of light through the glass threads of the new fiber optic line between Eureka and Cottonwood. (The light moves slower than it does in a vacuum because of refraction in the glass.)

The line is the new Highway 36 Humboldt-Trinity Counties Project. That's the official project title; but, ala the "Rock Island Line" or the "Pacific Surfliner," a more compelling moniker seems due. The Eureka Streak? The Cottonwood Carrier? The E-C Rider?

Opened for business last December, the line carries a bundle of 72 glass fibers. These fibers are paired to send signals heading in opposite directions on separate fibers. (With higher -- and more expensive -- technology, traffic can be sent in both directions on a single fiber by using different wavelengths of light to carry signals travelling in opposite directions.)

Before the line's existence, Internet travel into and out of Humboldt County relied largely on one fiber optic line running north-south, AT&T's along Highway 101. (Some traffic flowed via Garberville-based 101Netlinks' system, which transmits microwave signals from mountaintop to mountaintop between Ukiah and Eureka.)

The day after Christmas 2006, high winds took out AT&T's line, and with it the vast majority of the county's Internet service. A month later, a fire shut the line down. Later in 2007, trenching for highway construction cut AT&T's buried line -- twice. Each time the line was severed, most of Humboldt County's residents and businesses temporarily lost their lone tether to the Internet -- so no email, no web surfing, no online sales, big gaps in critical information -- for periods generally ranging from six to 12 hours.

In the wake of those dark days, a call rang out across the region: "Redundancy!"

Backed by a broad coalition and fronted by San Francisco-based tech company IP Networks Inc., a proposal to bring in another track from the east won the day. It wound up costing about $14.4 million, 40 percent of which was funded by state money. To many global villagers in Humboldt County, the undertaking was akin to the transcontinental railroad.

From July to November last year, the project's crews added new peaks to Pacific Gas and Electric Co.'s power-line towers. They strung new fiber lines above the existing high-voltage lines, high enough and tight enough to keep them from touching and to prevent "fiber galloping" in high winds.

According to IP Networks Vice President of Strategy and Implementation Mary-Lou Smulders, the project faced "enormous challenges," such as spanning huge ravines, "ups and downs" with property owners, getting cattle moved, and satisfying environmental regulations.

For example, to avoid the disruption of bird reproduction, the project commenced during non-nesting season. Smulders said, "It was ‘Wait.' ‘Wait.' ‘Wait.' ‘Wait.' Then, ‘Go!' ... And then -- and I never imagined this -- we were heading into the harvest season for the region's famous crop (marijuana)."

Line crews had trouble convincing growers that they did not represent the Drug Enforcement Agency. "We had to show them: ‘This is what our helicopter looks like. This is what our uniforms look like. We're not the DEA. All we're doing is pulling fiber,'" said Smulders.

At last, the proverbial golden spike was hammered as the last node was connected. It was ‘Hallelujah!' for the second coming of fiber to Humboldt County, with three dozen new pairs of fiber for all to share -- well, at least for those who buy into the line.

Of the 36 pairs, a dozen went to PG&E, essentially in exchange for use of its right-of-way and towers. IP Networks Inc. leases considerable remaining portions to two "anchor tenants," Suddenlink and 101Netlink, according to Smulders. (On a related note, Suddenlink's owners last month agreed to sell the company to private equity firm BC Partners and a Canadian pension fund.)

What Suddenlink and 101Netlink are leasing is redundancy, another fiber-optic way into and out of town that serves as a backup if the north-south line goes dark or a microwave linkage fails. That's the catch. The backup is only available to companies that pay for space on the line. (See "Occupy Broadband.") So ask your Internet provider: What route(s) do you use?

The new line is not being used to its full capacity yet. "We still have about four pairs of cable available and we'd be happy to sell them," Smulders said. "Actually, it's a long-term lease." Citing non-disclosure agreements, she would not reveal the cost or say who else is leasing space on the new east-west line.

Among those who have hopped aboard the new line, said Seth Johannesen, owner of 101Netlink, "We don't call it ‘redundant.' We call it ‘alternate.'" He said his company uses both its own microwave relay to Ukiah and the new fiber "all of the time."

While Internet packets -- the little bundles of information that travel across the Web -- don't make the same trip twice, they now have another route available. Which routes they take are determined by protocols in place at routers along the way.

For example, the clearest, choicest route is determined by OSPF protocol -- that's Over Shortest Path First. Gauging milliseconds, OSPF finds the shortest route -- in time, not necessarily distance -- and takes into account the transmission quality at that milli-moment, because lines can degrade due to high traffic and other factors.

"If a network gets congested, routers learn," said Johannesen.

And if one line goes down, said Johannesen, the routers will detect that a section of track is not viable and send the packets elsewhere. Such was the case when a fierce storm took down a stretch of the new IP Networks east-west line last winter.

But unless wildfire, backhoe blades, high winds or other calamities strike, traffic flows over both fiber lines and the microwave system continuously.

If one of the key lines to Eureka fails, the routers will send data along an open line, but only if that data has a ticket to ride on it -- the same as in normal operations.

"Every core router knows its next door neighbor," said Johannesen. "If one of my routers can't talk to one of its neighbors, it doesn't really hit a brick wall. It's more of a communication back and forth, neighbors checking in and reporting back."

In this context, the neighbors may belong to competing telecommunications enterprises that need to cooperate and travel down each other's road in the vast, open, rough-and-tumble terrain of the Internet.

So, in the spirit of redundancy, let's review: if it has a pulse and a favorable policy, a main fiber-optic line will carry your email when the other line goes down -- but only if your Internet provider has bought or leased rights to the live line's fibers. Again, ask about it.

Like many neighborly relations along property lines, routing can get complicated with technical gymnastics required to get through hoops. Sometimes a pathway needs to be debugged. Sometimes trying to cross through a neighborhood can be downright dubious.

According to network engineer Ivan Pepelnjak (on techtarget.com), networks with routers that don't run proper protocol may have no idea how to route a packet of information toward its destination. Instead, they may divert it toward a different address block, which subsequently can get overloaded, creating what route-tenders call a "black hole."

"To identify a black hole in your network, perform a traceroute (sic) from your customer's network to a destination in the Internet," writes Pepelnjak. "The last router responding to the traceroute is one hop before the black hole."

You don't want to go there.

That's light years past Platina.

Sean Kearns of Arcata is a technical writer and freelance science journalist.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1