The light is fading at the Arcata Community Skate Park as Oliver Wallace begins another lap around the perimeter of the park, heading towards the big concrete bowl. He dips his bike over the edge of the bowl, rolls across the middle, and swoops up the other side, keeping one hand on the handlebars and reaching down to place his other hand on the lip of the bowl. In one smooth motion, he twists his body up and over, still on the bike, and lands on the other side, but the bike skitters out from under him, pedals scratching on the concrete as his feet slip off, and he lands hard. "Attempted hand-plant, 100, Oliver, 0," he mutters as he gets back on his bike and heads out for another lap and another try.

Wallace and his friends describe the sport of BMX as "grown men riding little kid's bikes," and the sport is enjoying a renaissance, according to local area riders. The sport first arose as a means for kids to emulate their motocross heroes in the mid-to-late 1970s, hence the name "BMX," which stands for "Bike Moto-Cross," an amalgamation of street tricks, dirt jumping, and more recently, vertical riding. Technological advancements in the bike industry and the overwhelming popularity of "X-Games" and other extreme sports markets have led to a sport that is, as Wallace says, "blowing up."

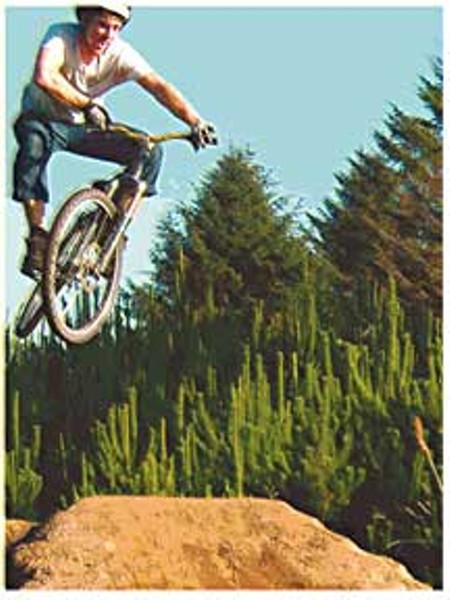

Sequoyah Faulk, a friend of Wallace's and fellow BMXer, describes the sport as "being on your own roller coaster, and you're in charge of where you want to go." In this case, the roller coaster is a small-framed bicycle, with 20-inch wheels and four "pegs" screwed into the front and rear of the bike, which allow the rider to ride on the bike, but not necessarily on the pedals. The seat is lowered flush to the frame, and many riders don't use brakes. The result is a remarkably simple, light, compact bike that can be "hucked" over jumps, curbs, stairs, and anything else the rider can roll up to, and over. "A lot of what we do is find stuff that's not meant to be ridden, and riding it," says Wallace, and he's not exaggerating.

Due to the popularity of the sport, many parks and tracks are being revived or built for BMX use, but lack of these venues doesn't stop riders like Faulk and Wallace from finding "features" to try tricks out on. "Stairs, wheelchair ramps, garbage cans, hand-rails, park benches, fountains -- if we can get the bike on it, we'll try to ride it," says Faulk, describing a tactic also known as "urban assault." Parks that are specially tailored for BMX, with jumps, ramps, bowls and ledges, are being built in more numbers in recent years than in any time in the past, and the industry is expanding.

David Bethuy, a wrencher at Revolution Bicycle Repair in Arcata, has been riding BMX for several years and has noticed a spike in bike sales over the past couple of years. "The early 1980s introduced 'free-style' riding to the sport, and it became popular for a while," says Bethuy. "And now the sport is enjoying another renaissance, because of its success in the X-Games, new technologies in bike parts and components, and a more specialized market. Small, rider-owned bike companies are keeping the sport 'custom,' and the market benefits from feedback from riders." The shop orders and stocks parts and bikes specifically for BMX riders, mostly from small companies.

Professional BMX riders can make up to $20,000 per contest, not including free bikes, gear and clothing from industry sponsors. Faulk, who has competed in the past in BMX competitions, says the sport should not be judged by contests alone. "There are many riders out there who don't have the money it takes to go to competitions who ride way better than the 'pros' out there, and have way smaller egos." For Faulk, it's the training and fun in riding BMX that counts, in addition to keeping the sport as "home-grown" as possible. Faulk received a degree in manufacturing technology last year, and plans to use his education and bike-shop experience to engineer and machine bikes that "don't break all the time and are made in the U.S.A."

Since many riders share local skate-parks with skateboarders, etiquette must be observed to ensure that bikers and skaters get along, and are able to share space in harmony. "I understand," says Wallace, "because for so long, skaters were the outlaws, and now that they have parks, and places they're allowed to ride, they don't want us coming in and getting in the way or hogging up the concrete." Technically, BMXers aren't allowed to use many skate-parks, unless they've been written into the insurance, but, says, Faulk, "If the cops roll by and see that everyone's wearing a helmet, and there aren't any super-little kids that may get landed on, they'll usually just cruise along."

Due to the "airborne" nature of the sport, consisting of vertical riding like ramps, half-pipes, and transitions -- steep corners and berms -- and the inevitability of landing on hard surfaces, BMX riders usually wear some form of protection, mandatory at most parks. "I broke my tibia, collarbone, and fingers, and have a metal plate screwed into my knee," Faulk says, "and I've knocked myself out wearing a helmet, so I'm not about to go riding around without gear." The rewards, however, are worth the risks.

Wallace likens the sport to breakdancing, a "street" form of dancing that combines acrobatic moves in a style that is both jerky and flowing, and often performed on concrete or asphalt, so the dancer can slide around. "When I ride," says Wallace, "my bike becomes an extension of my body, an expression of my creative energy. There's a focus and a release, once you decide what trick you're going to do and pull it off."

Faulk echoes this sentiment and views BMX biking as "life-affirming." Faulk admits, "Sometimes I'm so scared of a trick that it will keep me up at night, trying to figure out how to do it. Then, you put it all on the line, roll your bike up to it, and if you land it, the feeling of satisfaction and relief is so sweet."

And if you don't land it, "at least you tried," says Wallace, who is taking one last lap around the park as the streetlights turn on overhead and the last kid leaves the skatepark. He heads for the bowl and dips back in over the lip, soaring up the other side. His arc is higher this time, and he twists and turns his body and bike in a well-practiced maneuver, and for a second, he is suspended in mid-air, in an incongruous dance with gravity and concrete.

The Gravity Pirates

by ELISE CASTLE

The bike rack outside is full, with mountain bikes double- and triple-locked to each other, and more bikes are leaning against the wall inside. The room darkens, and hoots and hollers erupt from the audience as a large skull-and-crossbones materializes on the movie screen, accompanied by loud punk rock. "Yeah Justin," someone yells as the film's intro credits begin to roll, and the large crowd settles in for the screening of the newest down-hill mountain-biking documentary. Justin Graves stands in the back of the room, surveying the audience with a smile as people applaud, cringe and laugh during his edited footage of down-hill bike racing, crashes, and rider profiles.

These are the Gravity Pirates -- a close-knit crew of down-hill mountain-bikers from Humboldt County who are enjoying the fruits of their labors, documented by Graves and other riders. Many of them have helped build the trails that appear on the screen; trails that bear the local landmarks of towering redwood trees, verdant ferns, and slick mud corrugated with tire treads. Blood and sweat have been shed on these tracks, and riders have experienced both victory and defeat as they pit themselves against each other and the force of gravity in a fast, bumpy ride to the finish line.

Matt Snyder, head bike technician at Henderson Sports in Eureka, remembers when the Gravity Pirates formed, nearly seven years ago. "We made a flier announcing this 'race' that would take place on Tish Tang Ridge, in Hoopa," says Snyder, "and distributed it to local area bike shops and by word of mouth." Winter is normally "off-season" for mountain-bikers, but a good turnout of riders showed up for the event, which had no cash prizes but did offer some bike products from the industry's sponsors. "They just wanted to ride and have fun," Snyder says, "and it didn't matter that all they won was some new tires or fenders for their bikes. They were there because they ride together as friends anyway, and the competitive edge allowed for an extra incentive to better their skills and watch how other bikers rode."

The inaugural race was so successful that Snyder and friends, including Graves, decided to start holding races throughout the winter season. "We would show up to the track, move some dirt around with shovels, bring a clock out, and call it a race," says Snyder. Over the next few years, the Gravity Pirates, a name coined by Graves, has hosted races that have drawn riders from Southern Oregon and Redding to the Bay Area. "We called ourselves 'pirates' because we were basically trespassing on private property and looting all the good trails," says Graves, "and the 'gravity' part is just what happens when you throw yourself down a hill on a bike at speed. The Gravity Pirates is essentially a club that started in response to the demand for more challenging trails, and has continued on its own momentum."

In addition, the club provides manpower for building new trails and maintaining old ones, a sort of "if you build it, they will come" sentiment that was being echoed within the local mountain-biking community. Most of the trail maintenance is done with shovels, rakes, saws and hedge-clippers -- opening up routes where brush has overgrown, removing stumps and logs across the trail and smoothing the terrain. Other trail features are also added, such as "berms" -- sloping turns that allow riders to take corners quickly -- and "kickers" -- raised sections built up on the trail that allow bikers to launch themselves that much faster and farther down the hill. Many riders also build jump routes in their back yards, using backhoes and other earth-movers to create custom "parks," and some have been known to ride bikes off the roofs of their houses in attempt to "catch even more air."

While the Gravity Pirates were enjoying underground success as a local biking club, they were limited to areas that were, according to Snyder, "way out in the boonies or super hush-hush." Due to the high-risk reputation of down-hill mountain-biking, many locally sanctioned trails were "off-limits" to the Gravity Pirates, for insurance reasons, and private property was becoming increasingly difficult to 'poach,' particularly as the size of the events and number of riders grew.

Graves is credited with making the club "legit": facilitating permits, interfacing with the various land management bureaucracies, and promoting events. "The majority of our events take place on Hoopa tribal reservation land," says Graves, "and everybody's happy, because we get to ride without having to always look over our shoulders, and Hoopa gets a boost to their economy from the visitors that come to our events." In addition to promoting and competing in races, Graves built a website for the Gravity Pirates that he continues to maintain, and has made two full-length documentaries from footage taken by himself and other riders. "Someone always has a camera on rides or at races," Graves says, "and I go through hours of video clips -- editing, putting it to music, and packaging the footage into a product that can be distributed." He plans to submit his latest project to national and global film festivals once the director's cut is finished.

Graves was able to begin this side venture of the Gravity Pirates due to "forced down-time." In the spring of 2003, he broke his back while riding at Rock Quarries, a jumble of large boulders and loose gravel in the Jacoby Creek watershed. Down-hill mountain-biking is rife with risk, and though riders wear protective gear, injuries are common and sometimes quite serious. Footage in Graves' documentary shows fantastic crashes as bikers "huck" themselves off 20-foot boulders and down steep, rutted terrain. Many of the riders interviewed on camera had lacerations and bruises that were in various stages of healing. "My wife is used to it," says Snyder, "but she still tells me to be careful and not get hurt every time I go out."

Snyder and other riders began training in down-hill mountain biking in the early 1990s, when mountain-bike technology was still relatively new. "I grew up riding BMX and doing moto-cross," Snyder says, "and just naturally drifted over to mountain-biking once I saw that bikes were becoming more fully suspended, but for a while we were riding hard-tails on these trails, which to me seems crazy now." In mountain-bike lingo, "hard-tails" are lighter "cross-country" bike frames with shocks on only the front forks of the bikes, and smaller tires.

The standard down-hill mountain-bike is "fully-suspended" -- shocks on the front and rear of the bike that allow the frame to "travel" up and down on its suspension, similar to shocks on an off-road vehicle. In addition, the frame is usually steel, rather than aluminum, which makes for a heavier bike, and the tires are thick, with knobby treads. "Down-hill mountain-bike technology is still growing in leaps and bounds," says Graves, "using moto-cross and even NASCAR technology and applying it to bikes." The style of riding and the trails continue to evolve in response to this technology, and the delineation between "cross-country" riders and down-hill bikers is marked. "They're called 'down-hill' bikes because that's the only direction you can go on them," Graves says, "since they're too freaking heavy to ride up hills." Speed is a key element in down-hill racing, where riders choose the fastest route to the bottom, whether it's flying off of huge rocks or carving the side of the trail.

There is a new generation of Gravity Pirates emerging -- younger brothers and sons of the veteran riders. "My brother, Joel, used to tag along to all the races and started going out on rides with us when he was big enough to keep up," Graves says. "He's fast, too, and is starting to be a contender." Veteran Gravity Pirate Rob Rhall's son, Robbie, has been accompanying his father to events since he was young, and has placed so well in regional mountain-biking races that Rhall now devotes his time to taking his son to events, some as far as Nevada and Utah.

Both young riders are featured in Graves' documentary, and the audience at the screening applauds loudly and whistles when their profiles are introduced. The boys grin shyly, engulfed in the camaraderie and good-natured heckling by their fellow riders.

Many in the crowd are wearing black hooded sweatshirts with the Gravity Pirates' skull-and-crossbones printed on them, and various snatches of pirate lingo are tossed around. There is a feeling of pride and celebration in the room as Graves receives a loud and gracious applause at the end of the show. The Gravity Pirates as a club has become somewhat more sophisticated and well-known, but, as Graves says, "We're still the same punks that came tearing out of the hills, scattering rocks and running from rangers -- there's just more of us now." He smiles and heads back into the boisterous fray.

Comments (398)

Showing 1-25 of 398