The confetti of fallen leaves and needles littering the old logging road dampened our footsteps as we walked parallel to Bob Hill Gulch toward Ryan Creek. The canopy of alder and young conifers filtered the sun. I found it difficult to believe that just a short distance to the west were Cutten's homes, schools and shops.

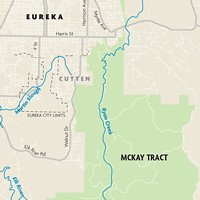

Its proximity to greater Eureka has often thrust the McKay Tract into the limelight. The total parcel is an expansive 7,600 acres of prime forestland that generated regular timber harvests for years. However, as the urban interface of the tract has become more complicated (from illegal motorcycle use to increased trespassing by walkers, joggers and campers), and landowner Green Diamond Resource Company's land management approach has evolved, the story of the McKay Tract has taken a different turn.

In 2012, Green Diamond announced it was negotiating with the Trust for Public Land and Humboldt County on an agreement that would, according to Green Diamond's Gary Rynearson, "include the opportunity for a county-owned community forest on the western side of the tract, and a conservation easement that would preclude future development on the eastern side of the property."

Deputy Director of Humboldt County Public Works Hank Seemann, one of my walking partners on this particular day, explained that the proposed transfer would come in two phases. The long and narrow 1,000-acre phase 1 section stretches for nearly 4 miles. A sliver of it follows the eastern perimeter of Eureka from Park Street on the north, then surrounds three sides of Redwood Acres to the parcel's southern boundary well past Cutten on the south. The 866-acre phase 2 section lies east and south of Ridgewood Drive.

Like the Arcata Community Forest, the proposed community forest within the McKay Tract would be selectively logged with the proceeds helping to offset the costs of maintenance and management. Initially, however, startup costs would exceed any return from the forest. The existing road network, Seemann said, has some sections requiring upgrades, while others should be decommissioned. The tract will need a system of multiuse trails and access points, expanded staffing and ranger or two may need to be hired.

The challenge is to keep a long-term perspective. There will be a time when a mature forest will yield regular and profitable harvests, trails will be well established and, as the Redwood Community Action Agency's Emily Sinkhorn observed, the community will have access to this natural wonder forever.

Ultimately, the Board of Supervisors will have to weigh the short-term subsidy against long-term benefits. As Seemann emphasized, the level of public interest and commitment will be critical. That includes fundraising, voicing support and the kind of hands-on help with trail building and responsible use that can help defray costs (See the story "Happy Trails," Nov. 7, 2013).

We continued on our walk turning back at Ryan Creek, which was still diminutive before big rains. Massive, dark stumps were silent ghosts among the lanky trees of this adolescent forest. There was a rattle and whisper from the few remaining leaves as a breeze passed through. Mushrooms peeked out from underneath ferns and brown duff on the forest floor. I could almost imagine what this world looked like back in the 1880s when Allan McKay bought up forests for lumber. Steam donkeys and trains hauled trees as big as 15 feet in diameter to the Eureka Slough where timber could be floated to the bay and to the mill between 'A' and 'B' streets on the waterfront.

In those early days, logging practices were scorched earth, brutal. Subsequent owners have done much more to restore water quality, protect wildlife habitats and replant trees. A 2005 analysis of Ryan Creek by the Redwood Community Action Agency found that rehabilitation efforts had "led to a significant improvement in watershed conditions and fisheries habitat." While work remains to be done, the McKay Tract is hardly an environmental wasteland.

More recently I paid a visit to Bill Windes, whose house is a two-acre in-holding surrounded by the phase 1 parcel. Windes, who moved into his nearly century-old house in 1977, was hired by Louisiana-Pacific to manage the McKay Tract. He pointed out landmarks as we scanned the landscape from his deck. Fingers of blackberry bushes and young alders were reclaiming the flat, bottom land that had been cultivated and ranched for years to feed the logging crews. The ranch house, once home to former County Supervisor Roger Rodoni, and its outbuildings were long gone. The spruce planted just east of Ryan Creek less than 20 years ago now obscures the channel and the R-Line road. I could just pick out the faint remnants of the railroad grade and the route of the old road to the ranch and Windes' home. There was a time when his house overlooked a flurry of motion, the screeching of engines and yells of mud-caked lumbermen. Nature finds little resistance from humans these days.

As we drank tea around his kitchen table, Windes, who has been retired for more than a decade now, told me he thought that this project was a "good opportunity for the community." There was no question in his mind, as he did some quick calculations, that even limited yield should eventually more than cover the cost of trails, policing and managing the forest. He felt that the greater presence of the community would actually reduce the homeless camps, garbage dumping, unleashed dogs and perhaps even the most intractable problem of motorcycles.

I later drove out to the far eastern end of Park Street to the edge of the slough, the north end of phase 1. It offered a fuller perspective on the importance of the McKay Tract and the natural beauty that keeps so many of us here — the sun dropping low, casting that winter light across the expanse of wetlands and the forest rising to the south, the flocks of noisy waterfowl and the high country of Kneeland, capped with a dusting of snow.

Comments