It was Halloween, and almost everyone was having a fine, silly time inside the big old house in Eureka. Never mind whose house. All that matters, really, is that despite the general merriment, the party had its scary moments. Take, for instance, the sudden conversation that sprang up in the kitchen among a number of College of the Redwoods faculty, of various disciplines, who were looking neither merry nor silly -- some hadn't even had the heart to put on a costume. One of them happened to mention that some newspaper (this one, actually) had recently done a story on the farm owned by the college and its apparent neglect. The paper, he said, "was missing the story -- completely. The farm -- puh. It's just a tiny little side issue compared with what's really going."

The real story, he said, is that CR is falling into an abyss, careening off the cliff, spinning into oblivion, dissipating into nothingness. OK, he didn't really put it that way. But he and the others in the kitchen were full of ill portent: CR is in trouble, they said. Enrollment had taken a nosedive. The budget followed it. Concurrently, the college was under an extended warning from the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges (part of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges). Not to mention that the college was president-less at the moment, following the departure of Casey Crabill in July for a new presidency at Raritan Valley College in New Jersey. And what about the new buildings underway on campus -- sure, the campus is underlain with earthquake faults, and some old buildings apparently could be compromised -- but was now the time to be building new structures? Squabbles were breaking out between faculty, administration and the Board of Trustees, indicating a deepening dysfunction.

But the financial crisis -- that was the biggie. Several teachers in the kitchen that night said they'd lost faith in their college and were, off the record, looking for new jobs at other colleges -- anywhere in the country that was hiring. "Anywhere," affirmed one woman. "We don't want to leave, we love it here, we've made our home here. But we need to stay employed."

Post-party, and in the light of day, one had to wonder: Is it really that bad at CR? Will that pretty little campus in the woodsy hills south of Eureka -- and its handy instructional sites flung far and wide between Mendocino and Del Norte counties -- become the latest messy red splotch on the North Coast economic (and cultural) landscape?

Well, some surmise that while CR's troubles are major they are not, in fact, life-threatening -- even if they have spawned panic in the CR community. Others say, look out -- there's reason for the panic.

No money

The worst news came in November: The college -- which currently has 336 permanent employees (part-time and full-time faculty, classified staff, managers and administrators) and, as of December, 618 part-time temporary faculty and classified staff (this number changes monthly) -- was looking at a $3 million, and possibly $4 million, deficit. The severity of the shortfall was a shock, and the result of a combination of factors.

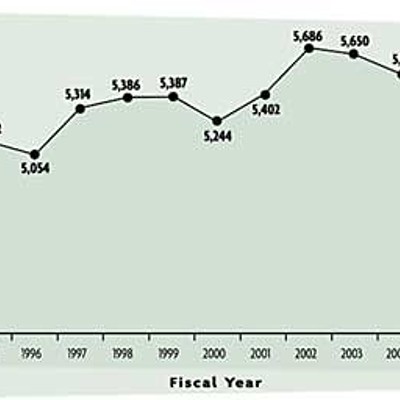

Enrollment is the biggest factor. It has persistently declined over the past four years, and, currently, for every lost full-time-equivalent student (FTES), the college is out $4,367 from the state. (FTES is equal to the total number of credits all students have signed up for at a given time, divided by a full course load of 30 credits per school year. Fees from students actually go into the state's coffers, and then the state uses the FTES number to determine how much tax money to give the college.) In academic year 2001-2002, when CR hit a peak in enrollment, there were 5,686 FTES (and the state gave colleges $4,675 per FTES). Enrollment has declined since then in fits and starts, with a particularly large decrease in 2004-2005 of 9.8 percent from the previous year (falling from 5,515 students to 4,974). In 2005-2006, there were 4,907 students -- a smaller drop, and perhaps reason for some hope at the beginning of 2006.

To compensate for lost FTES dollars, CR has been dipping into its reserves, said interim president/superintendent Jeff Bobbitt a couple weeks ago in an interview at his office on Eureka's main campus. Winter break had just begun and the buildings had emptied of most students and faculty. The wind was picking up -- through the picture windows of the administration building's offices you could see it tossing the branches of the young redwoods that dot the hills embracing the lush, groomed campus. With Bobbitt in his office was Paul DeMark, CR's director of communications and marketing.

Bobbitt, who has been vice president of academic affairs since 1997, said the enrollment decline at CR has, until recently, been mirroring a decline witnessed statewide at other community colleges.

"It has not been particularly alarming to us, because California has a history of rise and fall in enrollment," Bobbitt said. "The most common folklore is that the condition of the economy [determines it].When the economy is good, and there are a lot of jobs, students tend to take jobs and not go to college. When the economy is bad, students tend to go to college." In fact, said Bobbitt, when he came to CR in 1997 (from the University of Houston Downtown, where he was dean and a chemistry professor), "there was a general feeling of relief. Community colleges were coming out of a period of enrollment decline. And we did come out of it."

When it began to drop again after 2002, the administration figured eventually it would rise again. So under Crabill's direction, the college decided to use its reserve funds to balance the budget, said Bobbitt. "Prudent management dictates, when times are good, you put aside money for when times are bad. We attempt to maintain a significant balance of cash reserves. Our Board of Trustees, historically, would like to have a 6 percent reserve [6 percent of the budget]. That's 1 percent higher than the state requires -- and the state recently increased that, from 3 percent to 5 percent. We've had that [6 percent] until this decline."

Now CR's reserves are down to between 2 and 3 percent, he said. "And so, when we went into this fall semester, we went into what we believed a normal [fluctuation in enrollment based on historical trends]. And we believed it would reverse itself, and that enrollment would begin to rise [as it has, in fact, at other community college campuses in the state this year]. And it didn't."

The lowest enrollment yet is predicted for this academic year, 2006-2007, based on preliminary figures: 4,405 FTES. That's 500 fewer FTES than last year -- a 10.2 percent drop. If the projection holds true, the college will be receiving some $5 million less in FTES money than it did at its peak in 2002.

Then came Senate Bill 361, passed in September, which simplified the formula for calculating how much money the state gives to colleges.

"The old formula didn't account for the fact that some colleges operate out of a single location, and others, like College of the Redwoods, out of several," said Bobbitt. "I think we are the largest geographical district, out of 72 colleges in the state, which gives us greater challenges in meeting the needs of students." CR operates a main campus in Eureka, smaller campuses in Del Norte and Mendocino counties, and has several instructional sites in downtown Eureka, Arcata and elsewhere. "We think it's very important to maintain all those instructional sites and provide them with advisers, instructors and tutors. That gives us a built-in institutional cost that the old formula didn't account for. So one of the advantages of the new formula is it will account for that built-in cost. That's the good news. The bad news is, the money allocated for those institutional costs seems to be a moving target."

In mid-summer, and again in October, the state told CR it would be getting $750,000 each for the Del Norte and Mendocino campuses -- a total of $1.5 million extra. "In November, they did a recalculation -- now we'll be getting $250,000 for each of those two sites," Bobbitt said. "That's a $1 million decrease in what we were expecting. So that's one of the big uncertainties that remain. It'll be March, maybe April, before we know. We hope for the best, but we're preparing for the worst."

Meanwhile, CR's violation of the "50 Percent Law" in the past couple of years may mean it has to return several hundred thousand dollars to the state. Under the rule, 50 percent of a community college's budget is supposed to be spent on direct instructional costs -- faculty salaries and benefits, said Bobbitt. CR has fallen below that required percentage in the past couple of years. "We'd been reducing part-time faculty salaries, and we'd had more faculty members given special projects -- administrative tasks. The penalty is, if you fall below, they hold back that amount from you." The college might have to return up to $500,000 to the state, but has applied for an exemption from law, citing its financial troubles. In mid-December, Bobbitt and his chief financial officer went to Sacramento and spent three hours in the Chancellor's office talking about the exemption request.

But even if they get the exemption, and regardless of the outcome of SB 361 calculations, the biggest challenge facing CR remains: the disturbing drop in enrollment, and what to do about it.

Body snatchers

And now for the five-million-dollar question: Why are fewer and fewer students coming to College of the Redwoods?

Everybody's got theories.

"Now we're thinking, maybe enrollment is not based on the economy," Bobbitt said. "So, we're trying to understand that. It may be systemic -- something going on in our [college] community that is reducing the number of students we have."

Perhaps it's simply because Humboldt County's high school population is also in a decline, and that the region, in general, is graying, said DeMark. Maybe higher housing costs and the decline of blue-collar jobs have contributed to the shift in demographics.

Another external contributor to declining enrollment could be the statewide increase in unit fees at community colleges over the past decade. "It was $11 when I got here, then $12, then $11, then $18, then $26," said Bobbitt. "But, remember, that enrollment fee only affects the students who pay it. Low-income students get a waiver, and about 60 percent of College of the Redwoods students qualify for the Governor's fee waiver. So, the enrollment fee change doesn't affect them."

"Although, psychologically it may have an effect," said DeMark.

A report published in April 2005 by the Chancellor's Office of the California Community Colleges did actually find some correlation between fee increases and enrollment. The report looked at the effects on enrollment of the fee increase from $11 to $18 per unit in Fall 2003, in combination with the impacts of course section offerings, namely in Physical Education and the Computer Sciences, in reaction to budget cuts in the CCC system. "There was a loss of enrollment from the 2002-03 to the 2003-04 academic years in all categories of students, but the most significant losses occurred in first-time and returning students (returning students are those who have enrolled previously, stopped out at some point, and returned to the system)," the report noted (emphasis included). "Some data indicate that both the colleges' rationing of resources due to budget reductions and the fee increase had substantial impact."

But the statewide decline might have been exacerbated at CR by some internal decisions made during former President Casey Crabill's tenure, suggest some.

On a balmy day in December, just as Fall semester was winding down, CR mathematics instructor and department chair Michael Butler sat outside a café talking about the trouble at his college. Butler has taught at CR for 17 years, and was a co-president of the Academic Senate a few years back. He said many faculty have lost confidence in the administration, and that "things started to go the wrong direction" during the six years Crabill was here. "One reason for the declining enrollment is not enough faculty," he said. "In 2004-2005, they were cutting whole sections of courses. The class was full of students, but there was no money to run it -- so they cut the class. But if you cut sections, you get into a death spiral."

No sections, no students. No students, no money. No money, no teachers, no sections, no students. And so on. It didn't help, said Butler, that CR's administration decided to get tough on registration procedures at the same time. "Our enrollment process has been really flawed, pretty much since 2002."

In 2002, CR placed restrictions on new students who scored poorly on their math or English placement tests, requiring them to take remedial courses before they could any of their classes of choice. Then, a couple years ago, CR also shortened the registration time in which students could drop or add classes, going from two weeks -- and sometimes three weeks -- to just one week and then just one day in which to add or drop a class. The idea, said Bobbitt, was to ensure higher success for students from the very start. But at a counselors conference this fall, which CR holds for local high school counselors, some counselors said these changes deterred some students.

"The overarching opinion was that we were making it too hard to come in and take a class," said Butler. "[The testing is] good, don't get me wrong, but the problem is, it's put barriers between students and the college. I think in a lot of ways it precipitated the decline in the student body." As for having only one day to add or drop a class, "if you miss the first day of class, you're out."

Arcata High School Counselor Kathi Olesen-Sanborn was particularly outspoken at the conference about the placement tests. In a phone interview in late December, she said that she thinks the placement tests, which are designed to allow CR to place students in the appropriate level English and math classes as well as to help students succeed in college, are, in essence, great.

"The problem is, if I have an automotive student -- not to pick on automotive students, but just as an example -- here in high school, and he wants to take automotive at CR but he doesn't pass the English exam, he has to take remedial English and reading," Olesen-Sanborn said. "He could go a semester -- or a year -- before he can get into the majority of the courses he wants. He loses motivation to attend CR.

"We have a lot of students looking at UTI -- Universal Technical Institute -- because they can go right in. They focus right on the Vo-tech system." UTI could draw even more students. "Before, to go to UTI, it was in Arizona. But a lot of our students still went there. Now, they're building one in Sacramento. It's opening Jan. 19. It costs $32,000 to go to UTI, so it's [more] expensive [than CR]. But at CR you could take two to three years to get through the program. Or, you could go one year at UTI. And a lot of students end up getting financial assistance, anyway."

Possible fixes

To tackle the enrollment crisis, CR formed an Enrollment Management Task Force, which identified nine points to consider for attracting and retaining students. Three of them have already been dealt with: One is to lengthen the registration period, and Interim President Bobbitt allows that might help. "The intention [of the shortened registration period] was to try to get to the point where students didn't miss more than one class," he said. "We think that may have been a little restrictive to students. So we'll go back to one week this coming spring semester." Two, CR has decided to loosen up on the placement test restrictions by offering "carrot" courses to students who don't do well in their math or English tests. Even if they have to take a remedial course, they won't have to wait to take an initial course in their preferred profession. And, three, CR is increasing the number of students who can be on the wait list to get into a class from five to seven.

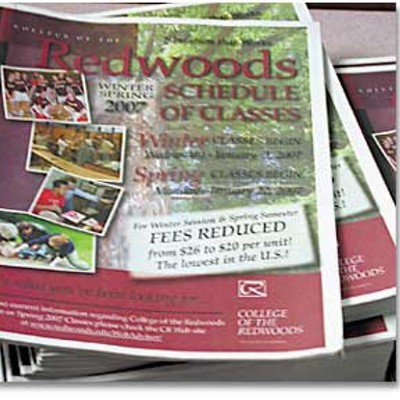

(Another change that might affect enrollment -- it's unknown, said Bobbitt -- is the state's reduction of per-unit fees from $26 to $20, starting this spring semester.)

Those are short-term fixes. Longer term strategies include trying "to understand better the reasons a student comes here," said Bobbitt. "Historically, students come to a community college instead of a university because it's just a whole lot cheaper," he said. "Community college is one of the biggest bargains in the state of California. So, even if a student is well-prepared and ready for university, if they can take two years of community college courses they can save a tremendous amount of money."

A community college also attracts students who don't want to leave their local area, he said. Yet another type of student is one who is not college-oriented in high school, but decides later to go to a university and has to catch up on college preparatory courses first. "A fourth category of student are those who are interested in immediate employment opportunities: repairing cars, or starting an internet business, or learning about computers. Another group comes just for fun -- they love art, or physical education."

Of those diverse types of students who choose community college, he said, the largest group consists of students who are thinking about continuing on at a university. "The second largest is those seeking employment training. And the smallest group is those seeking personal enrichment."

So what's affecting those categories? They don't know yet, but it's largely the job of CR's new Vice President of Student Learning Support Services, Keith Snow-Flamer, to find out. Snow-Flamer, who moved here from Chicago in August, sat in his office a couple of weeks ago looking out at a blustery day and noting how happy he was to not be gazing into a miserable snowstorm. He's not afraid of CR's problems.

"Although the college has problems, I see opportunities," he said.

Snow-Flamer is heading up the new enrollment management task force, and is planning numerous surveys of the student population similar to ones he's conducted in the past, including at McHenry County College in suburban Chicago. McHenry suffered declining enrollment, but gradually began to turn around.

"It appears as though new students as well as adult and continuing students are either dropping out completely or not continuing," he said of CR. "What we're trying to figure out is ... what they're all about, what their hotbuttons are, their goals.*Internally,*we are going to look at what courses are available, what times they're available -- and survey the students. We'll look at making sure we're not putting any barriers to students' success. Externally, we're looking at -- and Paul [DeMark] has done a good job with this -- what potential students think about College of the Redwoods, and what things CR has to do to attract students here -- particularly adult students. And the counselors told us we need to pay more attention to the high schools. And, how can we go past the high schools and go to the elementary schools and junior high schools? Outreach -- to motivate students to go to college, and to consider College of the Redwoods. We also need to wrestle with the huge issue of retention. Our retention percentage is not that good, to be honest. But we have to identify what we mean by retention. And if there are any gaps in students' needs. This is a survey in the back of my mind -- an exit survey [as they leave CR]. Next fall, the surveys should go out."

Snow-Flamer said the exit interviews were useful at McHenry, where enrollment issues were similar with one major exception: "Here, we have a lot more poor students."

Other long-term enrollment-boosting strategies are marketing, image building and looking at staff levels. And, added Paul DeMark, who also sat in on the interview with Snow-Flamer, CR will look at expanding some of the instructional sites to increase accessibility.

Bobbitt, meanwhile, said CR is taking into account the possibility of enrollment not recovering."We're not absolutely sure this is going to be a permanent change," Bobbitt said. "But it might be. We are preparing to become a smaller college [if we need to be]." That means the college will carry on in the same hardtack mode of late: not re-filling positions when someone retires, re-structuring class schedules, reducing section offerings taught by part-time faculty and canceling sections with low enrollment. "We've also been experimenting with online classes [which could increase enrollment]."

And, yes, there could be layoffs in the future, he said. "When you've got a problem like this, you have to consider every possibility. You have to plan for the worst. The very last thing you want to do is take people's jobs away. I can't tell you that's an impossibility, and so I've tried to be very clear with everybody. We've got to do everything we can in front of that, in front of taking away jobs."

Lost faith

Well, if the disgruntled instructors at that Halloween party were any indication, faculty job loss lurks as a distinct threat. Butler, the math teacher, wasn't at that party, and he himself isn't actively seeking another job. "There's really a lot of good at CR," he said. "I love the students, I love the community."

But he agreed there is widespread talk of defection. "There are rumors that some of our better faculty are considering leaving. There isn't a single faculty that hasn't thought about it."

Many faculty are particularly worried about the accreditation warning that has hung over the college since January 2006. Twice the accreditation team visited in CR, and twice found the same problems -- despite disagreement from CR's administration on certain points. Among the things CR needs to work on are integrating planning and evaluation with the budgeting process ("program review"), dealing with its financial crisis and dwindling reserves, and reinstating a long-defunct "institutional research office" so that someone is gathering hard data on enrollment trends, student demographics, what students do post-CR, what factors determine a student's success at the college and what the community's real needs are. That, in turn, should better inform decisions. Butler points to one area in particular where an institutional researcher would have come in handy. "In the six years Casey was here, we had no institutional researcher," he said. "Casey, she was convinced this community needed a hospitality institute." So, he said, the college held a series of wine galas to fund a program startup. "We now have a culinary institute, but no money [to operate it]."

Bobbitt said a federal grant funding the office had dried up years ago, and the college only recently obtained a new grant, $1.6 million for five years, to start the office back up. CR hired an institutional researcher this summer -- but she retired a few months later for personal reasons.

Some faculty have grumbled that Crabill didn't take the accreditation reports seriously, and accuse her of neglecting to post the May updates from the accreditation commission -- containing the warning -- in order to make herself look good in her search for a new job. Some even think the college won't come off warning status this spring, and that the Chancellor's office might have to "send in a turnaround team," as one faculty member put it.

The Chancellor's Office did not return our phone calls by press time. But Crabill, in an e-mail on Tuesday, responded: "I can't imagine that anyone in the college community was unclear about what the accreditation response was or what action it required. I can say that I accepted this new position in mid-April. CR was visited in May. ... A report from that visit went to the commission's June meeting, and the college received the response in early July, at which point those who were on campus during the summer began working on the next response. I might also suggest that accreditation results are posted not only by the college but also by the commission." Crabill added that she "fully believe[s] that the college can and will come together to move its mission forward."

Bobbitt, meanwhile, has found the silver lining in the accreditation storm cloud. "It wasn't surprising that we needed to improve," he said. "The surprise was that the warning action was taken, rather than just recommendations. In hindsight, I think it was good for us. It motivated us. And it's working. The accreditation system is a system of improvements ... it has really focused our attention on where we need to improve. We're hoping that they're sufficiently satisfied and take us off warning in June. If they don't do that, they can continue the warning status. A warning typically has a maximum of two years."

Academic Senate Co-President Kerry Mayer lists accreditation among the top serious issues facing the college. "Accreditation, that's pretty much the bottom line," she said late last month. "That's the basis of everything."

But now a breakdown in collegiality has cast a nasty pall over the already suffering campus. In December, the co-presidents of the Academic Senate walked out of the Board of Trustees' meeting in a huff. Since October, said Co-President Kerry Mayer a couple weeks after the meeting, they'd been talking with the board about a breach in the shared-governance process that College of the Redwoods operates under in which the board, the administration and the faculty jointly make decisions. The issue involves a state law that says if a college employs someone temporarily at more than 60 percent employment (based roughly on teaching load units) for more than two semesters in a three-year period, that person has the right to be hired for full employment. Well, at least four part-time faculty have been working more than 60 percent, and in June the violations came to light. Bobbitt says that perhaps one of the violations of the 60 percent rule was an accident. "And in some others, it was done with acknowledgment of the risk," he said. Crabill, in her e-mail, said that "as a small college in a fairly remote part of the state, CR sometimes has difficulty finding enough qualified part-time faculty to meet student need, particularly when a full-time faculty was absent for some reason. We believed that in cases in which a full-time faculty was on some kind of leave (sabbatical, medical, unpaid) from their full-time position that the law allowed for a part-time faculty member to exceed 60 percent to cover that load, since the load technically belonged to the absent, tenured full-time faculty."

But what added to the academic senate's ire was the administration and board's decision, absent faculty input, to correct the violation and make the full-time appointments -- one with tenure. "We hire many, many part-time faculty members -- we couldn't do our job without them," Mayer said. But the decision to make full-time hires generally involves a process in which faculty rank in order of importance the positions that should be filled first, and then the three prongs of CR government make a joint decision. The process is especially critical in times of budget cuts, since full-time hires can mean added costs. In August, a faculty member called Trustee Bruce Emad at home to express her concerns about the issue. Emad, in an interview last week, said he told her he'd rather the whole board discuss it. They did, and in October they formed an ad hoc committee to further sort things out. The committee was just about to deliver its report to the Board in November, when, as Emad sees it, the Academic Senate jumped the gun and issued a series of resolutions. "It was bunch of whereases and, basically, it was judge, jury and executioner," Emad said. The resolutions demanded that the Board "follow the Education Code" and "support administrators/employees ... who refuse to violate laws/regulations" and "direct the current and future administrations ... to establish an electronic monitoring process for monitoring the contracts" of part-time faculty and that the Board "hold administrators accountable."

"Frankly, I was insulted," said Emad. And he said so at the November meeting. Which in turn insulted the Academic Senate, whose presidents refused to participate in the December meeting. "We perceive that we were treated rudely," said Mayer. After Emad's speech chiding the senate -- in which he said he didn't have to "reiterate his credentials as a board member" and that the faculty was fast losing him "as a trustee that has always supported faculty" -- Mayer said she thought, "Wow, that was kind of angry." So now there was not only a breakdown in shared governance, she said, but a collapse in civility. She asked for an apology from the board. But the board hasn't issued one. Says Emad: "I was very angry, and I was very emotional. But I was not rude. And of course the board did not make an apology -- I spoke for myself, not the board."

Not everyone backs the faculty in their complaints -- but it was hard to find people to go on record about it. One administrative employee said, off the record, that she thought the breakdown in communication between CR's three governing bodies is the result of the tough times in general, and the loss of Crabill: "While the parents are away, the kids go wild," she suggested. Another administrative employee said many people are feeling sadness at Crabill's departure, and anxiety about the future. But some faculty feel they were taken for a ride. "Jeff and Casey had a total disregard for California state law," Butler said, referring to the faculty appointments snafu and the violation of the 50-percent rule governing the amount of budget allocated to instruction.

But Butler also praised Crabill and Bobbitt. "Casey and Jeff did a really incredible job of recruiting faculty," Butler said. "[They] built one of the best faculties in the state of California. One of the ways they did that was by offering on of the best compensation packages in the state. [According to Bayside Associates, a consultant that ranks schools with respect to compensation], we went from the bottom quartile to among the top."

Is there hope?

The campus faces serious challenges -- which everyone, perhaps even the faculty senate, will resume talking about when the Board of Trustees next meets on Jan. 9. But Bobbitt speaks encouragingly. "Up until now, we have not eliminated any programs, we have not eliminated any services, and everything you can come here for you can still come here for," he said. "The community should not worry about the college going away. And I know what my job is. My job is to carry us forward." That is, until a new president is found and hired sometime this May or June.

And it's easy to imagine that, if a rainbow is to be found hovering over the stormy campus, it might very well come in the form of those same wonderful -- but worried -- faculty. "One thing you'll learn about the faculty out here," said Mayer, "is you're totally committed."

Butler -- a former diesel mechanic who discovered his love for mathematics at a community college in Santa Rosa -- put it more intimately. "When I say `we' [when talking about CR], it's because I have a big investment in CR, and in the financial health of the community," he said. "About 10 to 12 years ago I had a student come to me. He was taking an algebra class. He was going to get a certificate in electronics. He was in a halfway house and was getting his life cleaned up. He started [to get into math], fell in love with it. And now he's a tech in the research and development lab in Berkeley. Now here's a guy who was living in the bushes behind Monkey Ward, who's now at UC Berkeley. And that's a typical story. That happens a lot. And that's the reason we get up and go to work every day -- we're changing the world."

Comments