After sitting neglected in a Florida harbor for weeks, home only to some dirty dishes and a feral cat that lived in the engine room, the Coral Sea was wired for video and audio by Florida's Drug Enforcement Administration. The agency's undercover informant, a drug smuggler turned snitch, invited his partners and suppliers onto the blue and white ship, where they would discuss future business over dinner and drinks.

The DEA planned to use the informant Frank Brady to bust some of the biggest smugglers of the 1980s. He knew the network and had ins with some of the most wanted cocaine rings supplied by Pablo Escobar's infamous Medellin Cartel in Colombia. The operation was coined "The Albatross Sting," and the Coral Sea played a minor — but crucial — role in the operation, which went south in the end.

More than three decades later, the Coral Sea is a tool of academia. It's used by Humboldt State University students to learn research techniques and discover the natural world of marine biology as the school's research vessel. The 90-foot trawler has transformed from luxury yacht to a research vessel, decked out with a massive A-frame winch, with the ship's middle extended to fit two marine laboratories.

But throughout the ship, there are still glimpses of a history rich with characters and adventure, uncovered through a trail of dusty old newspaper headlines and photos. The vessel lives on the Humboldt Bay Harbor's storm dock and is currently captained by Scott Martin.

Martin, an ocean blown veteran of the sea, has seen his fair share of adventures, from commercial ship salvations to expeditions in South America. "Every day is a new day," Martin said of adventures on the Coral Sea. "And you never know what you're going to find."

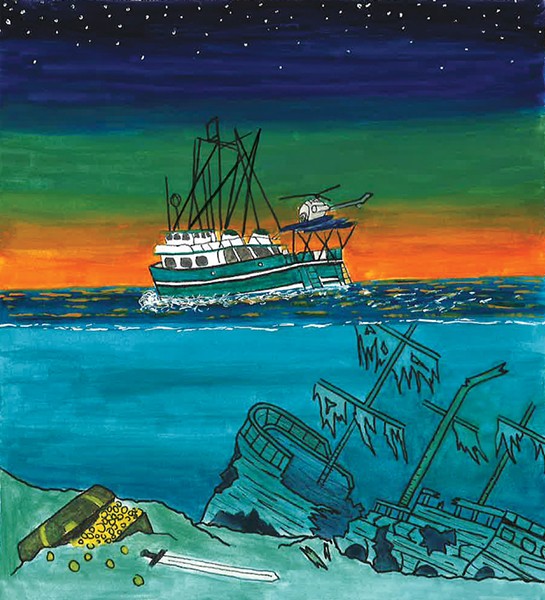

But the Coral Sea's current duties pale in comparison to its high-seas saga of diving dogs, shipwrecked treasure, foreign captivity, drug smugglers and DEA sting operations — past lives, the traces of which remain in a few original parts and some old framed photos on board.

Martin and the ship's engineer Jacob Fuller discovered the ship's history when Martin received a phone call from a distant relative of an old captain. Shortly after the phone conversation in January of 2014, he received a box containing old photos and newspaper clippings.

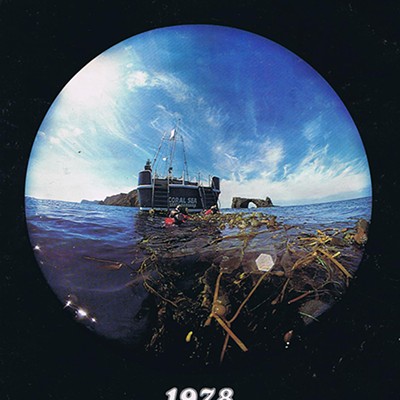

Martin pointed at a photo above one of the tables in the middle of the ship, inches away from a circular window looking out over the water. In the image, a dark blue and white vessel sits in cold Pacific waters. Positioned near the back is a matching helicopter with the words "Coral Sea" painted across it in bold white letters.

"We placed the photos where we thought they would be most appropriate," Martin said.

Air Traffic Control

Shortly after Ronald Markowski purchased the Coral Sea from the estate of an eccentric old dive master in the early 1980s, the vessel sat and swayed in a harbor down the road from a Florida airport. Markowski used the boat as a floating headquarters from which he radioed instructions to a team of pilots coming in from the Bahamas.

Markowski and his partners had ties to the Medellin Cartel and would fly turbo prop planes to Colombia to be loaded with marijuana and cocaine purchased from a man named Jose Antonio Cabrera-Sarmiento, better known as cartel kingpin Pepe Cabrera, whom the DEA had dubbed one of the world's largest cocaine suppliers. Markowski would then have the drugs flown to the Bahamas, where they would be repackaged and loaded onto twin-engine planes that had been stripped to their bare bones to hold as much weight as possible. They would fly the shipments into West Palm, Florida. There, the drugs would be distributed all over the Midwest.

The operation wound up in the crosshairs of the DEA's "Operation Skycaine" investigation, which culminated in the convictions of 42 smugglers. "Mastermind of Skycaine Narcotics Ring Found Guilty," read a 1984 headline of a Chicago Tribune story about Markowski's guilty pleas, which would later see him sentenced to 45 years in prison without the possibility of parole.

The Chicago Tribune reported that Markowski was the overseer of a "narcotics empire" that smuggled nearly 50,000 pounds of marijuana and 4,000 pounds of cocaine into the United States from Colombia. Among his partners was a man by the name of Frank Brady with a knack for eluding justice.

While Brady was caught, indicted and arrested for his alleged role in "Operation Skycaine," he reached a deal with the very DEA agents who'd seized the Coral Sea and ensnared Markowski, according to an article in the Los Angeles Times.

"[Brady] gleefully agreed to help hatch an elaborate sting aboard a $1 million yacht, the Coral Sea, that Florida Department of Law Enforcement agents had just seized from his former drug pilot, Ronald Markowski," reads a 1987 story in the the Palm Beach Post.

According to the Post, the Coral Sea was wired for sound and video by the DEA in order to spy on drug smugglers. Brady would invite known cocaine suppliers to have dinner and drinks onboard the yacht as the DEA cameras rolled.

The undercover operation was dubbed "The Albatross Sting" because the DEA was after one of Brady's associates who planned to smuggle 6,600 pounds of cocaine to Lake Okeechobee, Florida, using a Grumman Albatross seaplane.

The sting changed course when DEA agents learned that Brady had continued to smuggle cocaine under their noses into the Miami River from the Bahamas and deemed Brady too loose a cannon for their war on drugs.

Brady, described by the Sun Sentinel as a millionaire rancher who made the country's most wanted fugitives list by fleeing arrest in 1983, was later apprehended in the parking lot of his Boca Raton, Florida condo in January of 1986.

Caught in a double cross with the DEA and former drug associates, Brady agreed to testify against one of his partners and, again, escaped conviction.

A Captain Character

Years before Markowski showed up on the DEA's radar, salty sea captain Glenn Miller would fill the master stateroom of his yacht with smoke from his wooden tobacco pipe and the sounds of blasting bluegrass music. The room, complete with a wooden finish and a bearskin rug, was completely soundproof and decked out in luxury, exactly Miller's taste.

Miller built and skippered the 85-foot diving vessel in Santa Barbara, California. He christened it the Coral Sea in 1974 and used the $3 million luxury yacht to charter scuba diving trips in the Channel Islands.

Claudette Delanoeye worked on the vessel with Miller when she was in college, washing dishes and helping out with the scuba diving charters. She said Miller outfitted the ship — then the largest vessel in Santa Barbara — to be completely unique.

Miller's luxurious master bedroom even had his own bathtub. "You could have a party down there and nobody would even know," Delanoeye said.

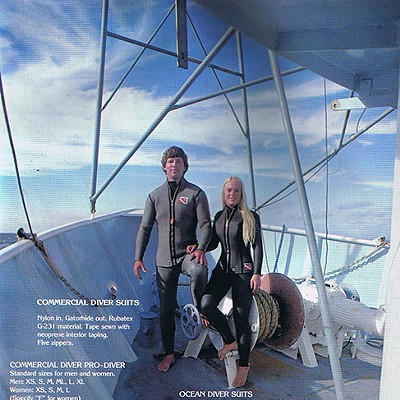

The yacht featured state-of-the-art scuba diving technology, as well as its own helicopter perched boldly on the ship's stern. Delanoeye said Miller used the helicopter mostly to fly to rodeos in Santa Barbara, leaving his son Zach Miller in charge of the charter.

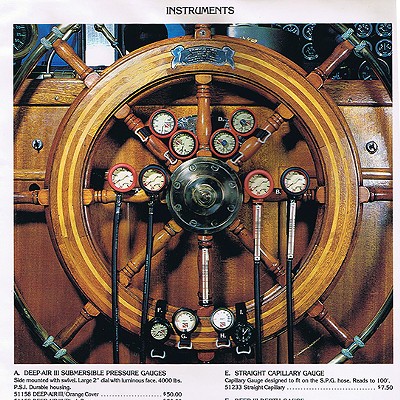

Miller's boat was so beautiful that outdoor company White Stag shot an entire 1979 diving catalog on board. "He made it a global expedition boat," Delanoeye said.

Miller obtained a handful of awards during his time on the Coral Sea, according to Delanoeye, including one from the U.S. Navy after one of its submarines surfaced in need of repairs and Miller came to its aide.

Sailing at Miller's side as first mate of the Coral Sea in these early years was a springer spaniel — Mac the Diving Dog — that loved chasing seals and drying himself in clients' gear bags.

An old photo of Mac can still be found in the ship's berthing area, right next to some bunk beds. "Supposedly, they would put a weight belt on him and throw him in," Fuller said, laughing at an old photo of Mac wearing some retro goggles.

Fuller and the ship's current captain placed the old photo near the bunk beds because Mac liked rooting through people's sleeping bags looking for sandwiches while still dripping wet from his dives.

Delanoeye said Mac loved the ocean and when Miller would yell, "seal," the dog would run off the back of the boat and dive straight into the water. Mac wasn't Miller's only charismatic character around the vessel in those days — he also kept a parrot named Fred on board, as well as Suzie, a pet seal he'd nursed back to health.

"Mac was Mac — he was like Glenn — kind of an individual character," Delanoeye said, adding that Mac "would love to play with the seal." She said that Miller eventually got into some legal trouble over his right to own a seal and ended up letting Suzie go.

Under Miller's leadership, the Coral Sea's halls were lined with old photos documenting its adventures. Among them, a flattened frog was pinned to the wall with an old knife. Deloneye said the frog was from one of Miller's trips to Bali, where he accidently ran it over with his car. The old captain didn't want to forget his trip so the frog found its way to the wall.

Treasure Quest

One day in early 1981, Margaret Brandeis, one of Miller's divers, rolled a coral crusted cannonball under her sandal on the deck of the Coral Sea. "Where did this come from?" she asked.

"That's a cannonball off the Maravilla," Miller replied, according to Brandeis' autobiography and nonfiction novel Women Can Find Shipwrecks Too.

The exchange gave Brandeis her first taste of shipwrecked treasure, and opened a new chapter for both her and the Coral Sea.

She soon found herself gathering investors and finding an expert on Spanish Galleon shipwrecks from the 1700s. In short order, she chartered Miller and his ship for a year-long voyage to find sunken loot more than three centuries old.

According to Miller, the Coral Sea was completely decked out for treasure hunting. "Half the shit on this boat is just for treasure hunting," Miller told Brandeis, according to her book.

The vessel was outfitted with a tubular metal frame at the stern of the boat that supported propeller blasters and shot strong columns of water down to the sea floor, where they blew holes in the sand to reveal previously buried objects. It is still a method used for treasure hunting today.

But before Miller was comfortable leaving and sailing through international waters, he had a request: two anti-artillery missiles. He said he was worried about getting taken over by pirates in the Caribbean.

"I want something that will blow them out of the water before they get near us," Miller said, according to Brandeis' book.

The Coral Sea soon left port in search of Neustria Señora de las Maravillas, a ship that supposedly sunk in 1656 carrying with it a 750-ton, solid gold statue named the Madonna, as well as 250 tons of gold, silver gems and amethysts that were strewn across the Caribbean.

Cutting through the ocean on its way to Grand Cayman Island, northwest of Jamaica and closer to Cuba, the Coral Sea shuddered and began having problems with its generator. Tired and worn out, the ship came to a halt. The crew took this chance to rest as well and started diving in the water when they spotted a Colombian Navy boat steaming over the horizon.

According to Brandeis' book, Miller was ready to try and outrun the gunboat. Miller ordered his son to get in contact with the U.S. Coast Guard in Miami, while they stalled and pretended as if they were trying to maneuver around a reef, which bought them some time. The crew became terrified when they found out there was nothing the Coast Guard to do. Glenn Miller and the crew were forced to sit tight.

"Colombia [sic] Sailors Hold Local Boat at Gunpoint," read a headline in the Santa Barbara News-Press. According to the newspaper, the Colombian desk of the United State's Department of State was negotiating the release of the Coral Sea and its crew.

They were caught in a sticky situation but Delanoeye said they were able to leave after Miller contacted his congressman and several big newspapers. The engines fired and it looked like things were shaping up. But just as the vessel was ready to leave, five of the crew members told Brandeis and Miller they wanted to go home.

The voyage's problems continued. Five crew members wanted off and a disagreement between Brandeis and Miller left her scurrying for a new investor. Eventually, though, the Coral Sea set off again from West Palm Beach headed toward the Bahamas and the sunken Marvilla.

"We were finally on our way again to dig up treasure and the whole boat was alive with the feeling," Brandeis wrote, adding that they'd pinpointed their first diving site in the middle of the Bermuda Triangle.

The first day of diving turned out to be the best. According to Brandeis' book, the crew brought in 40 emeralds, a few hundred coins, two swords and some coral encrusted artifacts. In the end, the sum total of all of the loot turned out to be about $350,000, just enough to pay back all investors and break even.

Tired and drained, the Coral Sea's crew turned around and headed back to Florida.

"The bottom line on the treasure hunt is that the people involved got a lot of great tax write-offs," Zach Miller said in a May 25, 1987 Santa Barbara News-Press article.

The voyage left Brandeis no wealthier than when she'd she started.

Sailing into Retirement

Meghan Glazebrook, a senior marine biology major, leaned out and over the Coral Sea's green railing to get a glimpse of something in the distance.

"There are about 30 or more closer to shore," she heard the ship captain yell into the loudspeaker. She looked out on the calm ocean to see gray whales breaching across the seascape.

As the 90-foot research vessel shuddered to a stop miles offshore from the mouth of the Eel River, students prepared to take algae samples. When whales began to surround them, Glazebrook gripped the railing and scanned the waves looking for a blowhole. "There were whales everywhere," Glazebrook would later recall. "You could see the barnacles on them."

The day was clearer than most on the Pacific and Glazebrook said it was one of her favorite aboard the Coral Sea. She continues to study the ocean and hopes to one day build a career on the open seas aboard a similar vessel.

Enjoying a sleepy retirement, the Coral Sea calls the end of the last dock in the Eureka Harbor its home. During the school year, it leaves the bay almost every weekend. "It's pretty much a brand new boat now," Martin said. In addition to student expeditions, the ship also charters out to agencies like the National Weather Service and the U.S. Navy for research work.

After the Coral Sea's role in the war on drugs in Florida, the ship sat dormant until the Florida Department of Natural Resourses took an interest in the vessel. The agency's previous research vessel, the Hernan Cortez, was on its way out, so the agency purchased the Coral Sea at auction and sent it to Louisiana, where the one-time luxury yacht was cut in half, extended 15 feet in the middle and reborn as a research vessel.

The department would soon cancel most of its research projects and found little use for the now 90-foot research vessel. It put the boat in a boat up for auction in November of 1996.

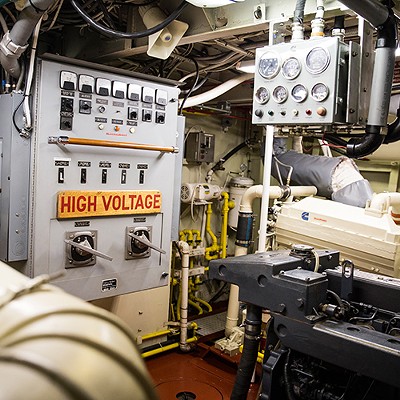

HSU purchased it a couple of years later for $418,000. Fuller, the current ship's engineer, said most students are unaware of the vessel's history.

On a recent morning, Fuller ducked his head down and stepped through the narrow stairway and into the ship's work room. In the corner sat a small, dusty black filing cabinet, its top drawer holding a manila envelope full of 40-year-old newspaper clippings and photos of a young, vibrant ship.

Fuller spread the old newspaper clippings and photos across a table in the Coral Sea, picking up a photo of Glenn Miller and the old Southern California crew standing in a row in front of the old vessel.

"It's amazing how someone's character still looms over a boat after 40 years," Fuller said.

Editor's note: This story was updated from a previous version to correct an error in the name of Margaret Brandeis' book. The Journal regrets the error.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2