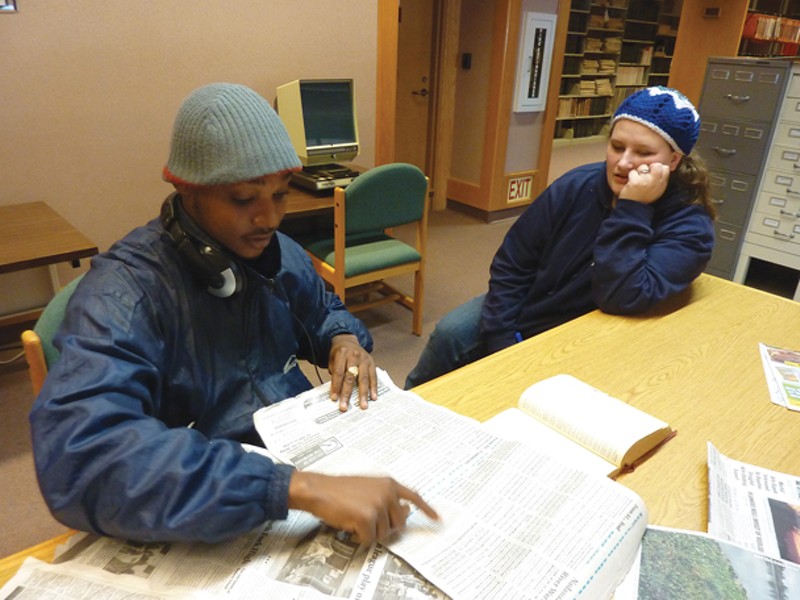

The young man was sitting alone on the second floor of the Humboldt County Library, headphones around his neck and a gray stocking cap smushed onto his head. He was focused intently on the newspaper page in front of him, manipulating a ball-point pen over it with such all-consuming concentration that he didn't notice when Rachel Fuentes, a 23-year-old in a navy blue hoodie and knit beanie, approached quietly and passed behind him, glancing over his shoulder on her way by. She walked a few steps beyond the end of the table, u-turned and sat down two chairs away.

"Hi," she said. "I'm doing a survey and I'm wondering if you'd be eligible to complete it." The truth, she admitted later, was that she'd already figured he'd be eligible. She'd seen what he was doing with the newspaper -- obsessively tracing the tiny letters on every other line of the newsprint -- and figured he had mental health issues and was probably homeless.

Fuentes, who graduated from Humboldt State University last May with a Master's in social work, is serving as the coordinator for a massive countywide canvassing effort -- the 2011 Point-In-Time homelessness survey. The goal of the survey is to conduct a comprehensive count of homeless people in the county, which is just as challenging and complicated as it sounds. The effort involves more than 50 local organizations, and it's organized through a collective of agencies known as the Humboldt Housing and Homeless Coalition, or HHHC. Last week, these 50-plus groups sent out more than 100 staff and volunteers to find and interview as many homeless folks as possible -- contacting them via shelters, food kitchens and resource centers, then searching for more in streets, camps and bushes.

The project, Fuentes explained, serves three main purposes: Most importantly, it allows local agencies to qualify for funding through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and other sources. Without a comprehensive count at least once every two years, such agencies would not qualify for federal grants. Secondly, the survey allows local service providers to assess the effectiveness of their programs. And thirdly, by analyzing the data these agencies can make well-informed decisions for the future.

The counts began locally in 2005 and continued for the next two years, though HHHC officials later determined that the 2006 and 2007 numbers were too low. They'd underestimated the scope of the undertaking, and so the results weren't accurate. In 2009, the HHHC redoubled its efforts, hired a project coordinator and came up with what they considered the most comprehensive survey of the Humboldt County homeless population to date.

They counted 1,913 people without homes, 416 of whom were children. Men outnumbered women, though women tended to be younger, with more of them in their 20s than in any other age group (compared to the 40s for men). Minorities, particularly those with Native American ancestry, comprised a higher proportion of the homeless population than the population generally. And more than 55 percent of the tallied homeless were found in Eureka.

This year's count coincided with many others across the state and the country. Locally, interviewers spent all day Wednesday and Thursday asking those who self-identify as homeless where they'd spent the night of Tuesday, Jan. 25 (the single point in time referenced in the survey). The survey is anonymous, with each subject given a unique identifier -- the first two letters of his or her last name and a date of birth. The questions, which were developed by an HHHC subcommittee, cover such topics as mental and physical disabilities, drug and alcohol problems, demographic information and personal history of homelessness. In exchange for taking the survey, subjects were given a free pair of socks or a knit hat like the one Fuentes was wearing. When the subject is amenable, the survey takes just a few minutes. Often it's more involved.

In the library, the young man looked up from his newspaper, and in a thin, Caribbean-inflected voice he said, "I'm trying to complete this myself and I can't complete it."

"What are you doing there?" Fuentes asked.

He sighed and looked in her general direction. "I probably should go back to Jamaica," he said. "I like people, I like to drink, you know? People I met, they kinda moved away. ... I'm not trying to be weird. I didn't want to put myself in trouble, because I can't go to the campus, take classes. So I'm just, like, reading. I'm trying to figure out my papers."

Specifically, he was trying to decipher codes, he said, like those used in World War II. But he was having trouble cracking them. Fuentes, working methodically and patiently, gradually managed to elicit responses to her questions, though the answers were often contradictory or confusing. The man was indeed homeless. Thirty years old. He'd spent Tuesday night (and many recent others) at the Eureka Rescue Mission. He was receiving Social Security checks and had recently spent some time at Sempervirens, Eureka's in-patient mental health hospital. As the interview wore on he became increasingly distracted, ignoring the questions or repeating them in a whisper as if trying to understand what they meant. He sometimes ignored them altogether and talked instead about his Arcata friends, who just seemed to disappear one day, or about codes and Starbucks and the lifting clouds that revealed buses and airplanes and friends from overseas.

Afterward, Fuentes said the man's symptoms suggested paranoia, possibly schizophrenia. The interview had taken more than 20 minutes -- longer than average but not unusually so, Fuentes said. Someone the previous night completed 20 surveys in just two just hours. There's no such thing as a typical interview.

Less than an hour later, Fuentes met up with two volunteers at a Chevron parking lot. One was Nicole Mayer, a skinny, fashionable, rapid-talking friend of Fuentes' from high school. The other was Tammy Reid, a tough and compact woman whose personal history involves the homeless camps they were about to explore. She explained that when her marriage fell apart more than a decade ago she stumbled back into her teenage drug habit, fell in love with a fellow addict named Paul and ended up living in a makeshift "cabin" on the river bar. Over the next few years she befriended her neighbors, people who for one reason or another, be it choice or circumstance, lived in tents and tarp-covered camps in the woods. Many are still there. Reid knows their names and habits, and she knows the system of trails that connects the camps. So when she heard about the survey she figured she could help.

"Paul introduced me to a whole new way of living," Reid said wistfully. He left her four years ago, she recalled, and she stayed in the cabin alone until someone -- could have been Paul or the sheriff's department, or maybe just kids on four-wheelers -- burned it down. She now lives in a Loleta trailer park and volunteers at the local food bank. But she misses living down here. (Fuentes requested that the Journal not identify the specific location of the encampments to avoid possible harassment from law enforcement or disapproving citizens.)

The three women drove to a nearby freeway off ramp -- Fuentes and Mayer in the latter's luxury SUV, Reid in her white Ford F-150 -- and parked in a roadside patch of gravel. After grabbing some surveys and a plastic bag full of socks and hats, they headed into the brush. Reid confidently led the way, following the railroad tracks for a hundred yards or so, then ducking onto a side path.

The path led down a hill to a ravine, across which spanned a bridge of sorts -- really just a narrow log with two wooden planks nailed to the top and, for a handrail, a rope tied between trees on opposite banks. "Announce yourself before you come down," Reid instructed after crossing the bridge. She charged ahead and, approaching a clearing, shouted, "Hello camp!"

The camp was impressive: Six tents were arranged in an "L" with tarps hung from trees to form a big-top-like canopy over a fire pit in the middle. Surrounding the pit were plastic and metal chairs, carpet remnants and a minivan bench seat serving as a couch. The residents had built a plastic sheet-walled pantry complete with a cooler and shelves and a floor made from shipping pallets. A four-wheeler and trailer holding a jet ski were parked along an embankment, though they appeared to have been there for years. A battery-powered radio played AC/DC.

The guests were greeted warmly by Dave, a big, gregarious man in a camouflage shirt and black baseball cap. His voice rumbled like a tailpipe. "Come in to camp!" he rattled happily. "This is our home. We're not homeless; we're at home." He and his camp-mates had already taken the survey (and, in that context, identified themselves as homeless). Nevertheless, he invited his visitors to stick around.

Reid told him she used to live down here, and she asked about some of her old friends. Were they still around? "Oh yeah," Dave said. After a few minutes, Dave walked over to one of the tents to roust another resident. "Where you at, buddy? You awake?" A voice inside muttered something indecipherable. "You got company," Dave hollered. Slowly, a white-bearded man tottered out from behind the tent flap and blinked in the evening sun. "Stand up, give ’em a smile!" Dave bellowed. "He's from the Journal, bro! Get your picture in the Journal!"

The older man plopped into a wheelchair and grinned. His name was Steve, and he'd been living in the camp for about 10 years, he said. Robert, a pensive young man in sunglasses, said he'd been there a couple months. Dave moved to the camp from Eureka two years ago after losing his wife to cancer, he said.

He continued the tour, showing off the camp's vegetable garden -- potatoes and carrots, soon to have some corn -- and the bobcat tracks in the sand nearby. He and Robert do community cleanup work with local churches in exchange for meals, he said. And they love living there: "We call it 'Camp Happy,'" Dave said proudly. "Nobody goes hungry; nobody goes lonely."

In 2009, more than half of the homeless adults surveyed in the county had been without a home for a year or more. Almost 19 percent had been homeless for more than five years. The HHHC concluded that these individuals would likely benefit from new federal programs for homelessness prevention and rapid re-housing. There are, of course, people like Dave, who choose to be homeless. But those who work directly with the homeless community say it would be a mistake to assume that's the rule rather than the exception.

"The majority of people would prefer to have some type of permanent, stable housing," said Stephanie Johnson, who, along with Fuentes, works as a care coordinator for Apartments First!, a transitional housing program run through Arcata House. Johnson served as the Point-In-Time survey coordinator in 2009, and she said that with the economic downturn, the situation has probably grown worse since then. People are falling into homelessness from a wider array of circumstances.

"It's never been people that just have mental health issues or substance abuse issues, " Johnson said in a phone interview last week. "But now ... we're seeing renters who had a stable place to live, but [then] their landlords had their home foreclosed on. And people that have lost their jobs. I would say the need is greater now."

Johnson said she's also seen an increase in concern from the community at large and the business community in particular. She attributes this trend to the fact that the problem has become more visible. "Everybody in this community, I imagine, is faced with the reality of homelessness just driving to and from work, or being downtown on the weekends," she said.

Fuentes agreed that the problem seems to be getting worse. And she said that even for people like Dave, the situation may not be as sunny as they let on. After leaving Dave's camp, the three women trekked through the woods to several more encampments. They spoke to a 57-year-old man who looked and sounded much older, hacking and coughing through tombstone teeth. He told them that he suffers from equilibrium problems due to brain and nerve damage. He answered as many questions as he could but declined the free socks.

The women then made their way to another camp and found Tom, an old acquaintance of Reid's, munching on a peanut butter-and-jelly sandwich by the embers of a dying fire. His camp was well-situated, with chairs, hay bales and a dome tent under a large tarp, a little wooden dresser holding a framed poster of the Beatles and a brindle mutt hunkered timidly by the tent. Tom said that in the five or so years that he's been living there off and on he's been visited by county supervisors Jimmy Smith and Clif Clendenen. And generally speaking, his needs are being met. (He receives monthly disability checks.) Later in the conversation, though, Tom admitted that he'd prefer to have a roof over his head. "Oh sure. It's just a matter of time."

With the sun setting, the women made their way back out of the labyrinth of trails to where they'd parked the vehicles. There they encountered a severe man in a tweed sport coat as he pedaled in on a bicycle, sitting board-straight, a clumsy puppy flopping around on the racks behind his seat. Rigid and fidgety, he answered a few survey questions before losing his patience and declaring he didn't want to participate.

"I've been 29 years outside and I really don't trust anybody, not even my own family," he said angrily. "Talk about paranoid. Every time I turn around somebody's backstabbing me. How can somebody be sleeping outside for 29 years and every fucking two days he's busted? ... If it's not two days it's two months. But there'll be no gettin' on his feet. Okay? Thirty years of my life. I should nuclear explode, okay? I don't get a wife, I don't get a kid, I don't get a career. I was gonna be an artist. I can't be jack shit other than a Dumpster diver, and everybody hates me or wants to murder and eliminate the homeless. There's vacant houses everywhere, and they're trying to say they're trying to help people, and it's a bunch of bull crap, cuz I know what the game is. ..."

He continued in this vein for a while before veering into a disjointed rant about the decline of America ("We don't owe China a dang thing!"), the Ten Commandments ("'Thou shall not steal,' you're not supposed to trespass") and a flurry of seemingly random tirades before eventually coming back full circle to his own plight. "They don't care what's happening really to homeless people. What they're trying to do is milk every situation. Anyway, Igottago!" And with that, he manically pedaled into the underbrush, leaving behind a residue of his rage, paranoia and lost faith in humanity.

The last camp to check belonged to Paul, Reid's former boyfriend, and she couldn't bear to go along. So while Fuentes and Mayer disappeared around a bluff, Reid stayed behind and opened up about her troubled past.

It's been almost 10 years since she's spoken with her three children, she said. She got into an argument with her eldest son in 2001, right before he left for an Air Force mission in Kuwait. He hasn't spoken to her since. She sent a letter once, but it was returned unopened. Perhaps because of her renewed meth habit, she was denied visitation rights for her other kids. She met Paul at a drug house in Rio Dell, and shortly thereafter they moved down to the homeless encampment. Soon, her other two kids stopped speaking to her, too. "They couldn't handle me; I couldn't handle them," Reid said.

She liked living down here. Loved it, even. She might have stayed if her cabin hadn't been burned to the ground. Not long after it happened, her ex-husband sent her a check for $40,000 -- her share of equity in the house they'd owned together -- and she bought a double-wide trailer in Loleta.

Reid looked at the bluff where the girls had disappeared. Did she miss Paul? "Mm hmm," she said. "I miss the kids, too. Seems like everybody that I've loved I've lost. And that's a hard one to live through. ... It breaks my heart, and I cry over it a lot. That's why I can't do methamphetamine anymore. I can't do it. It brings back all the nightmares and misery." Asked how she got clean she said, "I'm not. I still, um, it still comes my way and I try, you know, nine days here, a few days there."

Her voice had gone shaky and she was antsy. She started inching toward her truck, staring at the ground and fumbling with her keys. God, she said, gives her the strength to reach out and help people, like those she feeds at the food bank and her friends here in the camps. She stopped talking, took a deep breath a pointed anxiously to the bluff. "Now to get to Paul's camp, it's past there, through the trees, then go to the left," she said. "And that's where the girls went. OK, see ya later." She fled to her truck, started the engine and drove away in the settling darkness.

Fuentes and Mayer reemerged and climbed back into Mayer's SUV. They drove to a few other locations -- one where they shouted "Hello camp!" into the bushes and got only frenzied dog barks in response and another where they interviewed an Army vet named Matt who'd surrounded his camp with trip wire and who said he'd come to Humboldt County because this is where he wants to die.

The following day, Fuentes went out again, as did the legion of volunteers across the county, searching for the homeless, asking about their history, their current condition and where they'd slept Tuesday night. Fuentes said that despite their best efforts, the count can't possibly be definitive. "I think there's always going to be people that we miss; it's always going to be less than the actual population." That population is incredibly diverse, from those who've been homeless for years to those thrust into it suddenly; those suffering from severe mental health problems to those who've simply fallen on hard times. Their needs, Fuentes said, include better dental care, emergency services and transitional shelter. Systemic policy changes need to happen. But for all their complex problems, their primary need is deceptively simple, she said. They need affordable housing.

Comments (8)

Showing 1-8 of 8