Throughout the late 1980s and into the 1990s, HSU art professor Ellen Land-Weber made numerous visits to Scotia to document life in one of the last company towns in America through photographs and interviews. Only fragments of her work have been published; only a fragment of it is published here. In it, people of Scotia talk about their town and their company, revealing their pride and their memories of the place, as well as their concern for its future.

Most of the interviews excerpted here took place in early 1990, a period in the town's history that closely resembles the present day. The Pacific Lumber Company's takeover by the Houston-based Maxxam Corporation was only a few years prior; though Maxxam CEO Charles Hurwitz had allayed people's fears somewhat by investing in a new power plant, no one was absolutely certain what his intentions were. Earth First!, an activist group, had been picking up steam. "Redwood Summer," a months-long series of protests designed to bring attention to logging practices, was just around the corner. Several initiatives limiting harvesting would appear on the California ballot that fall. For the first time, residents of Scotia began to worry.

Even before Pacific Lumber declared bankruptcy earlier this year, the company announced that it would be selling off the town to its occupants - a bureaucratic headache that would require intense environmental review, but one that nonetheless stood to net the company several millions of dollars. Now, with bankruptcy declared, the subdivision of Scotia is on hold, and no one can be certain how it will proceed. If the bankruptcy court allows Pacific Lumber to continue as a business, the company will presumably reactivate its plans to subdivide the place and sell homes to its employees. If the company is dismantled - if creditors are allowed to foreclose - the process could get stickier. The banks that end up with title to the town will almost certainly seek to maximize their return in any way they can.

Late last year, two local engineering firms hired by the company and by the City of Rio Dell, which has considered annexing Scotia, undertook a review of the town's infrastructure and what sort of investment would be required to bring the town up to snuff. The company's engineers estimate that the town will require a minimum of $12.5 million in infrastructure investment if it is to be subdivided - already a significant cost, considering what the town's 274 homes would fetch on the open market. Who will spend that money? How will they recoup their costs? Will millworkers continue to live there, or will others move in, taking advantage of low prices, pretty houses and a few feet of elevation out of the fog?

Whatever the fate of the town of Scotia, one thing is certain: The way of life documented by Ellen Land-Weber, in the memories of town old-timers, is coming to a close. People will still work in the woods; redwoods will still be felled and milled; kids will still wander around the small-town streets on summer nights, holding a Coke bottle and dreaming about the world outside. But Scotia won't be Scotia anymore. And even back in 1990, in a corner of their minds, people knew it was coming.

- Hank Sims

TOWN

Gary Gundlach

Gary Gundlach: I was born here, in the local hospital, but we never actually lived here. ... But I can always remember coming out here, and looking at the place now I still have in my mind's eye visions of this place being so huge and just kind of awesome.

Ellen Land-Weber:The town?

Gary Gundlach: The town and the mill and the whole thing. It still does have some character. When you come off the freeway into here, it's like going into a different time. It just has a special thing about it.

Ellen Land-Weber:How would you describe what that special thing is?

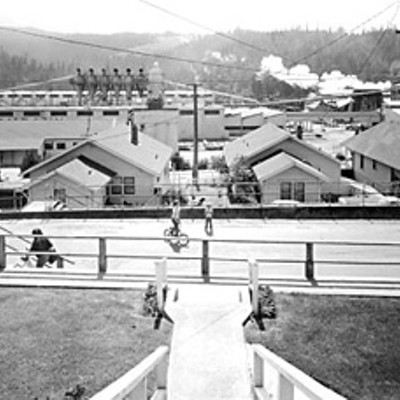

Gary Gundlach: Well, character, I guess. Because of the style of the houses. These are old houses, with the Men's Club and the Theater, I think, and the museum all out of redwood. It gives it that look. It has that old-time character. You've got some Victorian, maybe it's that kind of thing. A kind of Victorian look, because of the architecture of the buildings and the layout of the town. I think that everyone who writes about the place notes all the neat-looking houses and the layout.

Oscar and Polly Dillard

Oscar Dillard: When you walk down the street here, or down by the shops on the way to work, you hardly pass a face that you don't know ... I mean, it's that small a town for one thing, and eventually if people live here you're gonna get to know who they are, and so that's where you get the comfort of being at ease with everybody. You see 'em every day, usually.

Ellen Land-Weber:How many houses have you gone through?

Oscar Dillard: This is our fourth house. When we first lived here, we lived over on Fourth Street, and those homes are older homes - actually, the older homes are the smallest homes. ... So then we moved across the street into a little bit bigger house and it still wasn't big enough. This was as our boys were getting bigger, you know?

Ellen Land-Weber:How does the company do that? Do you apply if you want a different house?

Polly Dillard: When we first moved to town, yeah, we had to apply. ... We were paying like $50 a month rent. That was including our electric and water, you know? The house across the street had a little bit bigger living room and a lot bigger kitchen. I think we only paid like $65 there.

Jeff and Sherrin Ericksen

Ellen Land-Weber:I can't get over how well-kept the community is.

Jeff Ericksen: It's nice. I don't think there's any other place like this. I really don't. I don't know of any other place that takes as good of care of their people as PL does. It's one of the few company towns left. But it's changed. When I was growing up, I knew everybody. Now, I see people and I don't even know if they live in town or not. It's because of the turnover; there's so many younger people coming in.

Brian and Linda Franklin

Linda Franklin: I grew up in Rio Dell. There's a big difference between Rio Dell and Scotia, and I definitely would choose Scotia over Rio Dell.

Ellen Land-Weber:What's the big difference?

Linda Franklin: It's cleaner and quieter ... I don't want to sound really down on the people, but you have more welfare people that live in Rio Dell. Here in Scotia, it seems that everyone's basically on the same level and it's a good place for children to grow up. ... Here you don't see kids hanging all over the streets and stuff like you do in Rio Dell. That's all you see.

FAMILY

Oscar and Polly Dillard

Oscar Dillard: We've had a good life. My dad worked in the sawmill all his life, and he had a good life. Not to say there aren't other good lives out there. I'm all for someone who wants to try something else. In a situation like now ... had things stayed the way I hoped they would, I wouldn't be worried about my sons needing to learn something else. But now I feel they both need to learn everything they can about anything else besides working in the mills, because you can have that job five years or 10 years or you may not have one next year.

Polly Dillard: Our oldest son feels so secure here, but we have to say, "You know, Bill, maybe you shouldn't be buying a new truck." And he'll say, "Why, Mom? There's nothing gonna happen." But a lot of these young people don't or can't see what's coming. They're so secure here. They've got jobs now. They don't worry about it. It's like everything's going to be fine, but believe me, there's going to be people right here in town that won't even have enough money to live on. They've got large families and they don't think that's what's going to happen, but that's exactly what it's going to be.

Billy and Collyn Dillard

Billy Dillard: When you're a kid, it's like, "Oh, man, I've gotta move out of this place. I can't stand it! I want to go down south!" Then you go down there and you realize that there's just as much to do up here - probably more than there is to do down there, because it costs so much to live down there. If you don't have the money, if you're not making the money, you can't do all these things.

Collyn Dillard: I remember when we moved to San Luis Obispo and you were so upset because people wouldn't wave at you. The people he worked with on the job site doing plumbing, he said he'd wave to them and he'd get mad because they wouldn't wave back. That really upset you. Because they were so unfriendly, and he wasn't used to that. And now I always ask him, "Who was that? Who was that?" And he says, "I don't know - they waved so I waved back."

Ellen Land-Weber:So, did you meet in high school? You must have met in high school.

Billy Dillard: Yeah, in our junior year.

Ellen Land-Weber:And you got married right after high school?

Collyn Dillard: A year after high school, right after we graduated.

Ellen Land-Weber:How did you feel about moving to Scotia?

Collyn Dillard: Well, at the time I was excited because I wanted a house with a yard ... and we were paying $210 a month for a dinky little apartment with no garage, no yard, no pets, and I wanted to move to Scotia. [But] before we got married, I thought, "I don't want to live in Scotia."

Ellen Land-Weber:Why?

Collyn Dillard: I don't know. I guess at the time I kind of felt, maybe, it may have been because Billy grew up in Scotia, and I never knew anybody who lived in Scotia before I met Billy. At the time I felt - we're talking about an 18-year-old, now - like they were kind of cliquish or something. But that's not how it is at all. Everybody's really friendly and outgoing.

KIDS

Brian and Linda Franklin

Brian Franklin: Uptown has always been the nicer part of town.

Linda Franklin: The pond smells. You can't even park your car in front of the house, either, some of those houses down there. To me, the houses are too close together.

Brian Franklin: They have alleys down there, and it tends to be dusty in the summer. I lived down there most of my life, and there was always a rivalry between the kids downtown and the kinds uptown. We used to have football games and stuff - all the downtown kids against the uptown kids. Kids from downtown always tended to be a lot tougher. When I was growing up, they tended to be a lot tougher.

Ellen Land-Weber:Why do you think that is?

Brian Franklin: I think we played on the river bar and were a lot more outgoing, whereas with these kids up here... Of course, we all went to school together and stuff, but most of their parents worked in the office, and different jobs like that. They couldn't get their clothes dirty, and that sort of thing.

Linda Franklin: The higher-class people live uptown and the lower-class people lived downtown, it seemed like.

Jeff and Sherrin Ericksen

Ellen Land-Weber:What did you do to amuse yourself when you were growing up?

Jeff Ericksen: It could get boring. You know, there's not much to do, especially in the summer. What I'd do is walk to the store and get a Coke or something and sit in front of the post office and watch cars drive by. My friends and me liked to watch the tourists, or something. But they have a gym up there - a gymnasium and pool - and we spent a lot of time there. And then there's always Fortuna, which isn't far, but if you don't drive ...

SOLITUDE

Kendall Mangrum

Ellen Land-Weber:Has there been a change in the way Scotia has perceived itself?

Kendall Mangrum:Well, just that we're not a unique community like we used to be. We're like the rest of the world. Now it's caught up with us. It's the only way I can explain it. Five years ago, I never would have thought it would happen -- the changes, you know.

Ellen Land-Weber:You attribute it primarily to the takeover, or to ...

Kendall Mangrum:Well, no. Not necessarily the takeover. I think people were apprehensive about that, but things haven't changed. We're still working. The workers are working more. What really started it was the environmental movement the last couple of years. The workers are fed up. I hope things don't happen this summer, but I think we're going to have some bad incidents. When you start interfering with people's livelihood, you know, it ... I don't know.

Billy and Collyn Dillard

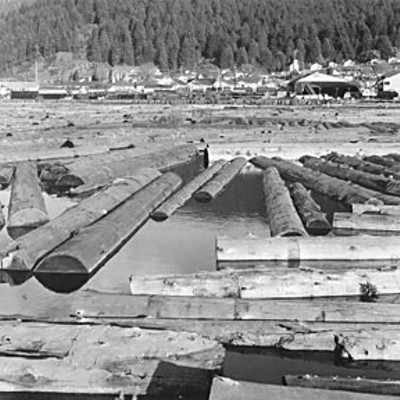

Billy Dillard: PL wants to keep clearcutting. I'm not for clearcutting at all; I don't agree with the clearcut. The select cut, I believe, is healthier for the environment itself. With the clearcut, the rivers suffer from it - we get a lot more silt in the river, so the fish have a hard time with it. I just don't agree with it.

Ellen Land-Weber:I'm just taking an adversary role, here - competitively, they have to clearcut, otherwise timber will cost more.

Billy Dillard: Right.

Ellen Land-Weber:So what do you say to that?

Billy Dillard: I don't agree with it. I think a lot of people who work for the company don't agree with it. ... I don't know a whole lot about forestry and all, but from what I've heard and what I've seen I just don't agree with it at all. ... But some people, they want to put a stop to everything. They want you to stop cutting trees, they want you to stop going on these roads, they want you to stop fishing, you know? What are you gonna be doing?

Jeff and Sherrin Ericksen

Jeff Ericksen: I'm against the environmentalists, because they're trying to take our jobs away. There has to be a happy medium. I don't want to see them clearcut every tree we got standing. I wouldn't mind seeing them slow down a bit, because then we would have a job for that much longer. But if they keep going at the rate they are, it's like 10 years, 20 at the most. Whereas if they went the other way, slowed it down, it could last 50, or an eternity, or until the company ceased to go.

Ellen Land-Weber:When you talk about the environmentalists ... what kind of confrontations? Has anything happened right here?

Sherrin Ericksen: We've had them come into our town a couple of times. Also, us as wives - we met them out at Yager Creek. Or did they show up that time?

Jeff Ericksen: A few did.

Sherrin Ericksen: It's just really hard. I mean, they have their point of view too, but someone needs to sit down and make a decision. It has to be. There has got to be a happy medium. They get angry, we get angry, then there's words on both sides and nobody's happy. I don't think the answer is shutting down the woods, but I don't think the answer is clearcutting, either. Somebody's got to make a decision, and whether Mr. Hurwitz owns all that land or not - like he says, it's his right if he wants to go out there and cut it all - but he has to take the environment into perspective.

Ellen Land-Weber:Do you think most of your neighbors feel the same way that you do about this?

Sherrin Ericksen: I think so. Some people don't want to speak out at all because they're afraid for their jobs. We don't want to lose our jobs. We want to keep it going.

CODA

Oscar and Polly Dillard

Polly Dillard: It was kind of neat on Church Street. At Christmas time, everybody on Church Street would decorate their house. People would put flags up, and it was just beautiful. We'd drive by and say, "I wish our street would look like that."

Oscar Dillard: Like on the Fourth of July, or Labor Day, or Memorial Day, everybody on that street would have their flags out.

Polly Dillard: Every flag on that street would be out, and it was absolutely beautiful.

Comments