Editor's Note: The following is an excerpt from local historian Jerry Rohde's recently released book, Both Sides of the Bluff: History of Humboldt County Places. An extensively researched chronicle more than a decade in the making, Rohde's book is filled with interesting material, from tales of murder and massacre to ingenuity and perserverence. Given our pick of material to run as an excerpt, the Journal selected a portion of Rohde's chapter on Scotia, the former Pacific Lumber Company town that is expected to be sold off to individual homeowners next year. Like Humboldt County, Scotia is a community in transition. In an effort to better understand the present, with Rohde's help, we take a look back.

One story, perhaps apocryphal but still worth repeating, claims that Scotia received its name because of a coin toss. The whites first called the place Forestville, but when it grew large enough to require a post office, it was found that this name was already in use by a town on the Russian River. Many of the workers at the mill town were from either New Brunswick or Nova Scotia, and it was decided to rename it for one of these Canadian provinces. A coin, denomination unspecified, was flipped and landed on the side designated "Scotia," and on July 9, 1888 the new name took effect.

Before either Forestville or Scotia existed there was an earlier community on the riverside flat, an Indian village called Tokenewolok by the Wiyot tribe and Kahs-cho ken-tel-te by the Lolahnkok branch of the Sinkyone Indians. The exact affiliation of the village is uncertain. It most likely belonged to the Bear River tribe, but perhaps was more closely associated with one of the upriver Indian groups.

In late February 1860 it appears that the village was attacked as part of the series of more than a dozen massacres that included the one on Indian Island. The Humboldt Times reported that "a large ranch of Indians, above Eagle Prairie, on Eel river, was attacked, on Wednesday morning, and twenty-six diggers killed, mostly bucks, and among them some that are known to be desperate villains."

It is probable that this massacre ended with the destruction of the village, as no further mention of it can be located. Later in 1860, William Shively, a resident of nearby Eagle Prairie, reportedly participated in a "round-up" of local Indians, who were then taken to an unspecified reservation.

After the Indians were either killed or removed, there is no record of anyone inhabiting the area until 1874, when Henry H. Niebur acquired 152 acres there from the United States land office. The Surveyor General's map of 1883 shows a "prairie" where the Scotia business district later developed but no sign of roads, trails, or houses. At some point Niebur "owned and operated a sash and door mill at the [later] site of . . . [the] Scotia medical center." His mill burned in the late 1880s.

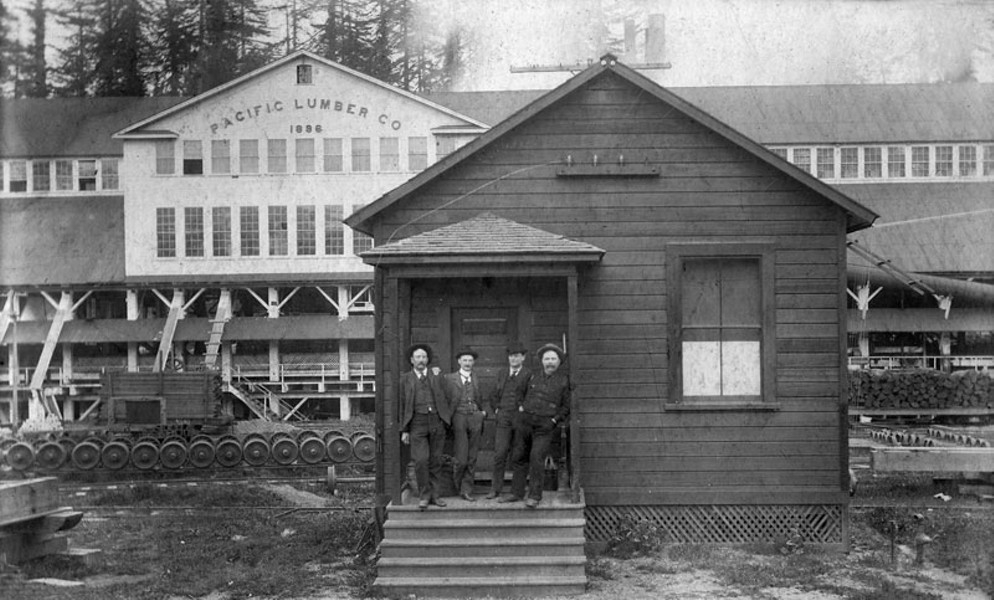

By 1886 another structure was rising on the flat. That April, The Pacific Lumber Company (PL) had 150 workers busy erecting an 80-by-200 foot sawmill that began operating the following March. This sudden activity was a long time in coming. PL had been founded way back in 1869, with an initial land base of almost 11,000 acres along the Eel River. Why the company waited 17 years before building its initial mill is quite a story. [And one that can be found elsewhere In Rohde's book.]

As it finally readied for action in the mid-1880s, PL considered two sites for its mill and town. Both were at the northern end of the company's timber holdings, thereby assuring that the mill's lumber products traveled the shortest possible distance to reach PL's shipping dock at Fields Landing. One potential location was the large, fairly open flat called Eagle Prairie, much of which was owned by Lorenzo Painter. The other site was Niebur's property which was just upriver and across the Eel from Painter's parcel. There was also a prairie there, although smaller. In the end, Niebur's property was selected and Eagle Prairie bypassed. The exact reason for this choice is uncertain; some accounts claim Painter wanted too much for a right-of-way, while another version states that he only asked for a train station on the prairie. In any case, PL chose the flat to the south, which had two effects on the route of the company's railroad. First, it eliminated the two bridges that would have been required to cross the Eel, one at either end of Eagle Prairie. Second, it forced the rail line to run along what became known as the Scotia Bluffs, a spectacularly scenic but unstable sedimentary landform that all but assured the periodic blockage or destruction of the tracks.

The choice to bypass Eagle Prairie was not made in ignorance of the topography. Two of PL's owners, John A. Paxton and Allen Curtis, traveled "by buckboard, on horseback and afoot," and "surveyed every foot of the land and water under their dominion." Both men had earlier helped build the Nevada Central Railway, which ultimately involved laying track on a 7 percent grade. The pair thus already knew something about pushing a rail line through rugged country but were undaunted by the dire prognostic provided by their chosen route.

George Douglas oversaw the start of the company's railroad. Douglas, like Paxton and Curtis, had helped construct the Nevada Central, and he brought with him a crew of Chinese laborers who had worked on building that line and others in that state. They first bridged the Van Duzen and then worked south towards the mill site. The route along the Scotia Bluffs required one trestle that was 1,200 feet long. Timber for construction was floated down the Eel from the riverside flat that later became Shively. The line, which at the time was called the Humboldt and Eel River Railroad, was completed between Alton and the mill site in August 1885.

The following April work commenced on the sawmill, which occupied a 17-acre parcel at what had become known as Forestville. James Rigby, another Nevadan and PL co-owner, supervised its construction. The first mill was built, like the railroad trestles, with timbers hewn by William Shively near his home at Bluff Prairie, a location that subsequently took the name of the hewer. The mill began sawing in March 1887. Within a year "the company was the largest lumber producer in the county." PL's lengthy somnolence had ended.

Then, in mid-1888, came the name-altering coin toss and Forestville became Scotia. By the following year the town had grown as if on steroids; it had 300 houses, a Fraternal Hall that held both school classes and church services, a store, drugstore, post office, telegraph office, hotel, wine and liquor store, and (perhaps because of the easy availability of wine and liquor) a justice of the peace. An adjunct to the community that probably also came within the JP's purview was the Green Goose, described, with euphemistic trepidation, as "a resort comparable to those common to all of the lumber and cow towns of the time." Owned by Gene Emerson and his wife, the Green Goose initially operated at the later site of Scotia's picnic grounds. At first this location was suitably distant from the respectable residential section of town, but as Scotia spread southward, PL encouraged the Goose to take flight. This was duly accomplished by a payment of $10,000 to the Emersons, and the Goose promptly migrated a short distance upriver. The further expansion of Scotia prompted the Goose to again flap its wings, landing at its third, southernmost, and final, location, where it resided "until local option prohibition closed it forever."

While the Green Goose was usually the hottest place in town, it briefly yielded the honor on July 6, 1895, when Mill A went alight and burned down in a single hour. Scotia had "a well trained volunteer fire department" and "a water supply with tremendous nozzle pressure," but with a heavy wind blowing, the flames nonetheless sped onward, quickly consuming "the cookhouse, planing mill, mill offices, a large warehouse and two stores." The firefighters managed to save several other buildings, including the hotel and President Curtis's house, but then, "as the fire spread to the lumber yard and with the terrific wind carrying red hot sheets of metal roofing hundreds of yards, the weary firefighters called for help." In Eureka, Fire Chief Pratt loaded a steam fire engine and 50 firemen onto a train of flatcars and sped south toward Scotia. Once there, they joined the locals in trying to save the rest of the town. It wasn't easy: "The heat was so intense that the men were compelled to work behind screens of wet blankets held by their comrades, while others of the men were only enabled to work by being kept wet with the hose." In the end they saved the machine shops, round house, hall, hotel, and numerous dwellings.

The ashes of the old mill cooled, and the following spring 250 men were at work building what was touted as "the largest and most complete lumbering mill on the Pacific Coast." Soon the rebuilt Scotia was receiving rave reviews.

In 1911 Mill B came on line. Its three headrig saws, when added to the three at Mill A, more than doubled PL's cutting capacity. Further expansion followed in 1916 with the installation of dry kilns and the addition of more storage yards. Then came diversification. PL's six saws created lots of lumber, but the milling process also generated considerable waste. Over time the company found ways to convert much of the left-over material into useful products.

PALCO Wool, modestly promoted as "the insulation of the ages," was made of redwood bark. It reputedly possessed numerous attractive qualities: excellent thermal conductivity (.255 btu!), resistance to settling and shrinking, great durability, resistance to moisture, resistance to odors, low cost, ability to repel vermin, and resistance to fire. The lattermost attribute was artificially enhanced by being "Saferized to make it flame-proof." PALCO Wool was also used "in diesel engine oil filters, as a soil conditioner, [for] ceramic burn out filters, [as] cushioning for athletic fields, [for] packaging, [for] toy stuffing, and in furniture upholstering." PALCO Fiber "A" was an additionally refined product "used for blending with certain textile fibers." PALCO Fiber "AR" was "the ultimate refinement in bark fibers" and thus used for "battery separators, filter papers and numerous other special papers." Another bark-based material was PALCO Seal, which served "the oil industry as a drilling seal." Oil workers also utilized two bark dust products, PALCOTAN and PALCONATE, "as drill mud conditioners" and for related uses. The bark-dust twins also "found favor in the chemical industry as phenol and tannin replacements."

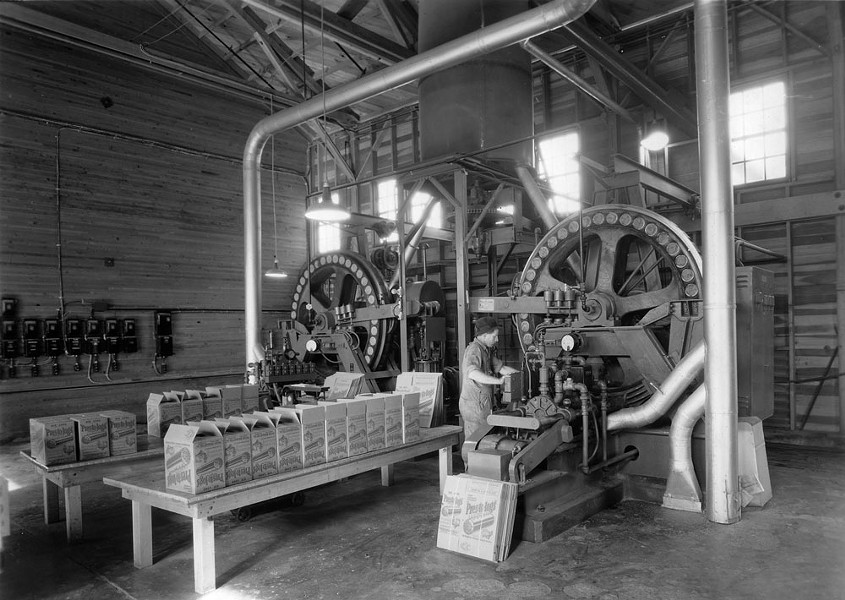

Certainly not Saferized was PL's other product, Pres-to-Logs. Made of sawdust, the perfectly symmetrical log cylinders had been invented in the 1930s by an engineer at the Potlatch Corporation in Lewiston, Idaho. The product proved so successful that by the late 1940s Potlatch had 18 machines working "around the clock seven days a week" to artificially rejoin wood fibers that the log milling process had torn asunder. By then, PL had four of its own Pres-to-Log machines in action and Weyerhauser Timber Company was running a dozen of the little log makers at Everett, Washington. Nor was production confined to just the U.S. Compressed logs were soon in production at such diverse locations as Peru, Yugoslavia, and Africa. Now Serbians could heat their houses as quickly as saying "npecto!"

Meanwhile, the town of Scotia kept growing. The 1920s saw a surge in the construction of community buildings. Two of them housed people. One was "a new hotel, the Mowatoc, [which] replaced the old hostelry on Main Street." It was likened to a small-scale version of "the grand resort hotels of the national parks" and later became known as the Scotia Inn. During the 1940s the Inn housed mostly PL employees and had only 18 rooms available to the public.

In 1929 PL built what was then the southernmost hospital in the county. It "offered medical services to workers for $1 per month." Nineteen years later the facility had two surgeons, 40 beds, and a staff of 40. The cost to workers had risen to $1.62 ½ per month.

Two other structures built during the 1920s, the Winema Theater and the Bank of Scotia, have become architectural landmarks.

There was more than architecture, fine as it was, to catch the eye in Scotia. In 1921 PL President John Emmert suggested that the town hold a contest to determine which residents had created the best lawns and gardens. The event found fertile ground in the yards and minds of Scotians, and by 1949 some 24 prizes were awarded annually. Fourth prize, worth $20, was given in memory of Emmert. It was won that year by Mr. and Mrs. P. Antongiovanni.

The prize money was small change compared to the profits pouring out of PL. Mills A and B were cutting 400,000 feet in an average day and running six days a week. PL had found another use for its scrap and sawdust, burning this "hog fuel" to generate steam for its power plant, which could in turn generate up to 18,000 horsepower of electricity.

Even the power of 18,000 horses was not enough to fully cut the PL forest, however. By 1951 the Saturday Evening Post could describe Scotia as the " hub of a 131,000-acre tree farm that somehow never gets completely harvested, because by the time three or four generations of tree fallers have cut around the circle, a new generation of redwood has matured. Thus Scotia is a lumberjack's dream of paradise come true."

And there were lots of lumberjacks to do the dreaming. PL employed some 950 workers, in the mills and forest, to make sure that paradise was a perpetually busy place. Some 12,000 visitors who took the mill tour each year could attest to the activity:

Puffing logging trains coming round the bend to dump logs with a tidal splash into the ponds; log peelers snaking them out again to strip off the stringy red bark which is shredded into redwood wool for insulation; band-saw operators slicing up logs as though they were carrots or onions; pilers stacking the boards into finished lumber, cabinets, doors and 100 other products.

Workers and their families either lived in Scotia or across the Eel River at Rio Dell. The latter were called "hopers," because they hoped to get a house in Scotia. Hopers in 1951 outnumbered residents two to one.

Hope rewarded meant a house maintained by PL and rented for $7 per room per month. Although operating as a small city, Scotia levied no taxes, yet provided a school, churches, community meetinghouses, a baseball diamond, and a redwood-shaded park near the Eel with its own barbecue pits. Such benefits induced one PL worker, Tommy Thompson, to stay on the job for over 53 years. Small wonder that hopers sprang eternal.

Scotia, in the 1950s, was one of four company-owned mill towns in Humboldt County and was no doubt the most famous. Picturesquely situated along U.S. Highway 101 on a flat above the Eel, it was on display for both tourists and locals, and, with its huge mill buildings, Winema Theater, and Bank of Scotia, it became one of the area's premier scenic attractions.

While the Humboldt Times saw Scotia as a "model community" and the Saturday Evening Post likened the town to Humboldt's version of heaven, such views were at least partly the result of PL's effective PR. The company's relationship with its workers may have been better than that of some of the other operators in redwood country, but it was not always harmonious.

In 1903 PL decided to integrate paradise by bringing in a group of black and Filipino workers. When the newcomers were fed at the regular tables in the cookhouse, some of the white mill workers protested and were promptly fired. The rest of the mill crew then went on strike, to no effect.

All was then quiet until May 1907, when several Humboldt County mills were struck. Some 740 PL workers went out. Eleven mill owners united in their resistance to the strike, and by June "the strikers either left the county or returned to work."

Then, in May 1913, the men who operated PL's trains demanded a wage increase, were refused, and went on strike. PL first responded by putting together a scratch engine crew that included "Master Mechanic Buchanan, Manager Donald McDonald, Superintendent Speck and Assistant Superintendent Reynolds." The four men chose a modest task for their maiden voyage upon the tracks: running a switch engine across the Eel to haul meat from the Scotia slaughterhouse to the logging camp on the far side of the river. PL then brought in 16 strike-breakers from San Francisco, who were not told the true nature of their role until after their arrival. Most of the men then refused employment, including all of the prospective train engineers. Two days later two substitute engineers, who had failed to pass their qualifying examinations, were on duty when four rail cars ran away, "dashing down grade over a quarter of a mile ... before two of the cars jumped the track and were piled up." In October the strike was called off and 50 railroad workers returned to work.

The intense lumber strike that convulsed Humboldt County in 1935 apparently found little traction in Scotia. Some 733 PL employees signed a loyalty pledge to the company while only 38 refused.

Another timber workers' strike hit Humboldt County in January 1946. For a time all the local mills closed. PL shut down for six months but reopened in July, with "more than 50 pickets at the gates of Scotia." By October, all of the county's large mills were back in operation. When the strike ended in April 1948, it concluded the longest shutdown in any major industry in the country. The strikers had failed to gain their goals, chief of which was the institution of union shops.

When author Fred Taylor visited Scotia for his 1951 Saturday Evening Post article, he learned of ultra-loyal PL employees like Tommy Thompson but apparently ran into no former strikers. Or, if he did, he (or they) chose not to tell their stories. Instead, Taylor related accounts of such events as PL's annual Labor Day "outdoor feast" that fed 4,000 attendees "over a ton of hot barbecued beef" and let them wash it down with 3,000 bottles of beer. It may have been Labor Day, but the event was defined not by the workers but by the owners of The Pacific Lumber Company — the same people who defined the rest of paradise.

The days of Scotia's particular paradise were limited. The town endured major floods in 1955 and 1964, along with a 1992 combination earthquake and fire. These were nothing, however, compared to Charles Hurwitz's 1986 leveraged buyout of PL that hit Scotia like a Texas tornado. In 2008 the resource-depleted Pacific Lumber Company was reorganized as the newly formed Humboldt Redwood Company, ending PL's 139-year history. The community came under the control of the Town of Scotia Company, LLC.

Scotia's once-sparkling houses now show a decade or more of deferred maintenance. The tracks through town have long since ceased vibrating from train cars loaded with redwood logs. On the log pond itself a few ducks and about half a gaggle of geese patrol the nearly still water. The turmoil of PL's peak production years has been replaced by a sunny somnolence that Tommy Thompson and his ilk would likely have snarled at. Such scenes suggest that mortality is just around the corner, but walk east from the log pond to the next corner and you will see the Bank of Scotia building — a monument to permanence, whose dark weathered wood echoes the forest from which it was made. Ancient trees indeed were felled to build this structure, but here, at least, they were not sacrificed upon the altar of aggrandizement. Instead they were transformed into what is truly Scotia's Parthenon — a temple that, once beheld, touches something deep within the spirit. Touches the heart of Sequoia sempervirens, the ever-living redwood.

About the book, and its author

Both Sides of the Bluff is the first volume in Jerry Rohde's "History of Humboldt Places" series. More than 10 years in the making, it covers 31 locations in west-central Humboldt County, from Scotia to Fields Landing and from Hydesville to Centerville. It also includes a chapter on the Indian tribes of the area.

The book is illustrated with more than 200 photos and line drawings, along with more than a dozen maps. Numerous sidebars tell stand-alone stories while several appendixes cover larger accounts, such as the history of the Pacific Lumber Company and Fortuna's most famous bank robbery. Readers wanting more detailed information are referred to more than 2,500 endnotes and 32 pages of sources.

Rohde has co-authored five guidebooks to the Pacific Northwest, including Traveling the Trinity Highway. His shorter pieces have appeared regularly in the Humboldt Historian and occasionally in the North Coast Journal. He was also a columnist for the Redwood Record. For 14 years he has served as a historical and ethnogeographical consultant, working with the Cultural Resources Facility at Humboldt State University, various archaeologists, and several Indian tribes. With his wife, Gisela, he regularly teaches courses in Humboldt State's OLLI program, and for the last three years he has offered a community lecture series sponsored by Pierson Building Center.

Both Sides of the Bluff begins a historical journey that, when finished, will take readers around all of Humboldt County.

Rohde currently has seven book signings and lectures planned throughout the county in the coming weeks. For a full list of dates and locations, visit www.northcoastjournal.com.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2