Whether welcomed or dreaded, the inevitable return to school arrives next week for thousands of elementary, middle and high school students in Humboldt County.

As they approach their first day of class, many kindergarteners and students graduating to middle or high school will surely be anxious about fitting in and finding the bathrooms. For older students, disappointment over the end of summer may compete with excitement about sports, dating prospects and even learning. And some students will be looking forward to the routine and safety of school as a respite from homes that provide too little of either.

Parents will be going through their own emotions: the stress of buying school clothes and supplies; sharing their children's anxieties over new schools and new teachers; not to mention their own sense of impending freedom -- perhaps mixed with loneliness -- as children who have been around 24/7 return to the care of schools for six hours every weekday.

But what about teachers? What do they go through? How do they prepare? What do they look forward to and what do they worry about?

To find out, I spoke with three Humboldt County teachers, two veterans with 20 years or more in the classroom and one new teacher entering her third year of full-time teaching. They shared intimate details of their back-to-school rituals, the practical aspects, the emotions and even their first-day-of-school nightmares. They opened up about what it is that keeps them going through the school year: the weekends spent correcting papers; the nights spent planning activities; the sheer intensity of leading, managing and teaching 20 to 30 children five days a week.

A common theme was their sense that during the school year, there are no slack times. "You could literally work 24 hours a day and not run out of stuff to do," says Warren Blinn, a fifth-grade teacher at Alice Birney Elementary in Eureka. "Your work's never done," agrees Lisa Cardenas who teaches a Spanish immersion class at McKinleyville's Morris Elementary.

But all three said that the stressful demands of their jobs are more than compensated for by the nourishing joy of their daily interactions with students. "There are a lot of sweethearts that sit in those seats," says Pam Halstead of Fortuna High.

Right: Fortuna High's Pam Halstead gets very excited about the first day of school: "Kind of like right before a performance, it's thrilling." Photo by David Lawlor.

For Pam Halstead, the weeks before going back to school have been filled with study and preparation. She's drawing on what she learned at a week-long seminar in July to get ready for her chemistry class -- the first she has taught in several years -- and she's completing a report to justify her environmental science class" advanced placement status, a distinction that allows students to receive college credit.

Like most teachers, last week she went back to work for meetings and last-minute preparations. But as the first day of school approaches, Halstead, 48, will focus on those first moments when she'll be appearing in front of five groups of new and unknown adolescents. "It's extremely exciting, kind of like right before a performance, because you don't know the kids, and you're going to meet them for the first time," she says, sitting in her empty classroom on an afternoon in early August. "It's thrilling."

"The classroom allows me so much creativity in terms of sharing information with students, connecting with them and talking with them," she says. She also looks forward to renewing her relationships with co-workers. "I'm in other people's classrooms all the time and they are in mine. "How's it going? What's happening, What are you doing? How can we make this better?" This school is such a vital living place."

But Halstead's experience in the classroom wasn't always so positive. While at Humboldt State University, she chose teaching science over veterinary medicine, then got her first high school teaching job as a substitute in the early 1980s. "I was only 22 or 23, not much older than my students," she says. "And I cared too much about what they thought about me, which is a common mistake. Discipline problems were rampant, with spitwads and other items flying across the classroom. "Once a couple kids started fighting and one tried to throw the other out the window," she recalls with a shudder.

"I was young, naÔve and didn't know much about classroom control. I thought I could be friends with my students," she says. It took several years before she became confident in managing student behavior. Today, she describes having something of a sixth sense that allows her to know what's going on in every corner of her classroom. "My way of dealing with classroom discipline is to use humor. ... If I see a student doing something I'll mention it to the class. Not to publicly humiliate [the student] ... I'll do it in a way where they [can respond], like "Oh yeah, I guess I screwed up.'"

As she got the discipline tactics down, she noticed that she actually became more popular with her students. "Ironically, I think they like me a lot more now," she says. "My classroom is a safer place for kids to be, so they want to be more a part of the process rather than disrupting it."

Still, Halstead felt something was missing from her work. And in 1989 she figured out how to bring her passion for nature and ecology into her teaching. "I learned I needed to follow my passion in a sense, so after seven years of teaching I started the Fortuna Creeks Project," she says. "I wanted students to just get outside, get dirty and see the wonders that are out there in nature. As I got hooked into what turned me on, then I could turn them on."

She started by asking her biology classes what they saw when they looked at Fortuna's three creeks, Rohner, Strongs and Mill, all of which drain into the Eel River. "They said: "We see a big mess." There was a lot of garbage and neglect." Students made a model of the watersheds and began slogging through the creeks looking up close at the conditions. The more they saw, the more they wanted to take action, and soon the project became a student-run club advised by Halstead.

Displayed around Halstead's classroom are photos of past years" activities: students gathered triumphantly over mounds of furniture, tires and other trash recovered from creeks, students standing knee deep in creek pools testing for sediment depth. There are also photos of students staffing the school's Snack Shack at football games, an activity that earns money for an end-of-the-year trip.

Left:Pam Halstead's fortuna High classroom. Photo by David Lawlor.

As this year gets rolling, the first meeting of the club will be a big event for Halstead and the veteran members. "We're going to start with our officers [elected last year] and then advertise to get other people interested," she says. If this year is like previous years, the first meeting will be packed with 30 or 40 students. "It can be huge. This classroom can be filled with people at lunchtime," she says.

In accord with its traditions, the club will organize creek cleanups in the fall and spring, sell T-shirts at the September Apple Harvest Festival and plant trees on creek and river banks in the winter. This year the group is also going to put up signs -- designed by Halstead's husband, Ted, and Pete Nichols of Humboldt Baykeeper -- that warn against illegal dumping at a popular spot on the Eel River just south of town.

And as has been the case in previous years, Halstead predicts that the club will be a forum for debates over environmental issues. "We have kids who will say "I'm an Earth First! member" to kids whose families have worked at Palco for generations," she says. "They work together, so common ground is a huge thing that the Creeks Project gives the school."

The project is a lot of work, however, and along with planning curriculum and correcting papers, Halstead works an average of six hours every weekend. This has caused her to question her commitment to the club. "A couple of times in the past, I've thought "This is too much. What am I trying to do, kill myself?'" she says. "But it really does something for the kids." She talks about students who have gone on to be environmental science majors in college, and others who absorbed a community service and environmentalist ethic that will influence them the rest of their lives. "They've found something that's a niche for them, and it's often something they can take into a career."

As Lisa Cardenas prepares for her third year as a full-time teacher, she has been having some unsettling dreams. A recent one: "I was waiting in the staff room to make copies, and I asked someone, "How many minutes until school starts?" They said "Lisa, school started 15 minutes ago. So I rushed back to the classroom to find all the parents there waiting with their children."

Lisa Cardenas of McKinleyville's Morris Elementary works 50-60 hours a week prepping: "Maintaining a quick pace and high interest in every subject, every moment of the day is really hard." Photo by Yulia Weeks.

Her three-part antidote for such anxieties: prepare, prepare, prepare. "[From the beginning of school] up through the Christmas Break, I'm working 50 and 60 hours a week," she says. Her plan for a typical morning with her mixed second- and third-grade class is to start at 8:20 a.m. with spelling practice. "It's really important they have a task to do right away," she says. "They'll do a sentence edit and then they either count the vowels and clap out the syllables or write sentences with the spelling words."

While the kids do their spelling, Cardenas will pass out fluoride to students whose parents request it, take attendance, find out who plans to eat a school-made lunch and assist faltering students with their work. Then she'll correct the answers with the whole class and throw a few yoga poses into the mix somewhere, because she believes the exercise helps invigorate students. All that takes until about 8:45 a.m. "You have to maintain a quick pace and high interest, and knowing how to do that in every single subject and every moment of the day is really hard," says Cardenas.

Speaking in Morris" immaculate library, Cardenas projects incandescent energy and speaks quickly but clearly. It's easy to imagine her capturing the attention of 8- and 9-year-olds.

The 30-year-old Southern Californian found her way to Morris by a circuitous route. In her early 20s, while at University of California at Berkeley, she decided to find a career that would allow her to do what she calls "social good." Working in a summer program to tutor inner-city second graders hooked her on teaching. "I really, really enjoyed working with the kids," she recalls. "It didn't seem like work."

After graduating from college, she went to Mexico for a year to learn Spanish, something she wanted to accomplish for personal and professional reasons. Cardenas had actually grown up speaking Spanish, but her father, a Mexican immigrant who'd been teased harshly for his accent, insisted she speak only English at school and in public. "He said "I'm not having a daughter who speaks with an accent,'" Cardenas recalls.

Humboldt State University drew Cardenas and her husband to the North Coast. After getting her teaching credential, Cardenas knew it would be tough to get a job in Humboldt County, where the teaching profession is extremely tight due to declining enrollment.

Left: Mural at Morris Elementary. Photo by Yulia Weeks.

But Cardenas set her sights on Morris after she and her husband happened to buy a house nearby. She visualized herself walking to work there to teach in the Spanish immersion program. To her husband and friends, she began saying "all kinds of outlandish things about what it'd be like when I started working there, how nice the other teachers there were," she recalls. When she got the job, her belief in the power of positive thinking was affirmed, while her skeptical friends pointed out that it didn't hurt that she had completed a double major at Berkeley -- rhetoric and mass communications -- and that she was fluent and literate in Spanish.

In her classroom, the day is divided into two parts -- or you could call them hemispheres. The first half of each day is conducted in English, the second in Spanish. "At 11, I say "Ya vamos a cambiar a espaÒol.'" The transition is marked by dancing to music from different parts of the world, with Cardenas pointing out the music's origin on a map. "Dance is one of my passions and an easy way to fit social studies and movement PE into a five-minute period," she says.

Cardenas doesn't expect the English-speaking students in her class to become fluent Spanish speakers by the end of the year -- the program's goal is for students to be bilingual by seventh grade. "There are certain things they'll learn to say, like asking to go to the bathroom or telling me when they're done with their work -- "terminÈ,'" she says. "Sometimes they'll ask questions in Spanish, but they won't come up to me and start talking about their weekend in Spanish."

But their ability to understand Spanish develops quickly. And with students who have been in Spanish immersion since kindergarten, Cardenas fully expects to be able to teach even new math concepts like long division in Spanish.

For the very first days of this school year, Cardenas has planned icebreaker activities for the mornings in which kids can share things about themselves. The first day, she's tentatively planning to pass out paper hot-air balloons and instruct her students to inscribe their names, decorating balloons with stickers and markers as they wish. These will then go on the walls to create a sense of belonging.

"I think this year I'm going to read The Important Book [by Margaret Wise Brown]," says Cardenas. The book guides children in thinking about the important attributes of familiar objects: an apple, a pencil, the moon. "I'm going to have them write their own verse about themselves," she says. "I'll also have them write an ad for themselves [promoting] something they're good at, something they can teach."

She learned some of these exercises from a mentor, Charlene Crump of Arcata Elementary School, under whom Cardenas worked as a student teacher. "She really inspires me, so I like to talk to her before the year starts," says Cardenas.

As she evaluates her own progress, Cardenas says that she wants to become more nimble and flexible in situations where she can tell she's losing her students" interest. "Sometimes I'll get too caught up in being verbose and talking too much and trying to explain [something] in every way possible," she says. "If I teach a lesson that's too long ... some of the kids will check out. That's when behavior problems can start."

To improve, Cardenas draws support and ideas from her fellow teachers. "We've got a really great family at Morris," she says. "I've gone to other teachers about all kinds of things," especially strategies to deal with behavior problems and ways to teach difficult concepts.

Last March, during Eureka City Schools" Open Schools Week, I spent just about an hour in Warren Blinn's fifth-grade classroom at Alice Birney -- an hour so packed it felt like three. The class read and discussed part of a novel -- Gary Paulsen's The Hatchet . Students began a lesson on the Declaration of Independence, went outdoors to play a volleyball-like game called "over the wall" and reviewed the rules for capitalizing letters.

Warren Blinn of Eureka's Alice Birney Elementary masters classroom discipline with rewards, consequences and respect: "I give them respect and I get it back." Photo by David Lawlor.

But I was most struck by Blinn's ability to manage his 30 energetic fifth-graders, barely raising his voice in the process. He seemed to know just how much chair-shuffling to tolerate between lessons and the exact moment when a student's trip to the pencil sharpener was digressing into a flirty escapade. At one point, when side-talking went on longer than he wanted, he said calmly: "I'll count to three and I want your attention. One." Instantly, most of the class became quiet while a few still whispered. "Two. I have most people's attention but I'm still waiting for some." Peer pressure kicked in, and the laggards listened up.

When I chatted with Blinn earlier this month, he told me that it took him about five years of teaching to become comfortable managing behavior. "I feel pretty darned comfortable now, and I've seen it all," he says. "I've been in situations where the principal had to call the police. I've had really tough kids who already had probation officers."

At the beginning of this year, as in previous years, Blinn plans to orient students to his behavior procedures. He maintains a progressive daily warning system that starts with your name written on the board and ends with 15 minutes detention and a phone call home. There's a weekly raffle for pens or candy bars that you can only qualify for if you've done something good during the week. There's a wall chart that tracks your progress toward five consecutive weeks of good behavior, for which you get a free "A" on any homework assignment you turn in.

When kids are angry, he says he'll sometimes suggest they leave the classroom for a while. "I don't say "You're outta here,'" Blinn says. "I say, "Would you like some time to cool off outside?" or "I'll bet if you run a lap it'll help you cool off." They understand it's a choice ... and when they calm down, we can talk. Of course, if someone's being super-disruptive, I'll ask them to leave because they're affecting the learning environment for the whole class."

The key element, however, is respect. "I give them respect, I listen to them," he says, "and I get that back. When they learn you're on their side, they'll make an effort."

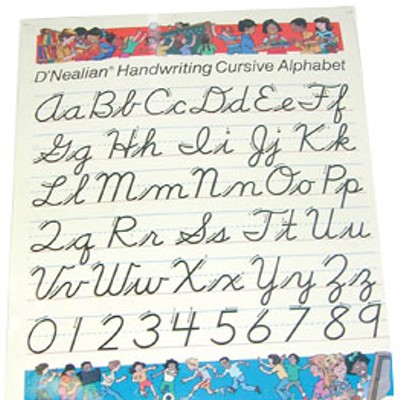

Handwriting chart in Warren Blinn's classroom.Photo by David Lawlor.

He also plans his school days meticulously, emphasizing a routine that he says gives his students a sense of order and stability. "At 8:10 we do math every day," he says. "At 8:40 we do reading. They get used to knowing exactly what time each subject is going to be taught."

Blinn, 57, came to teaching more than 20 years ago after volunteering at his children's elementary school. "I really like being around kids," he says. "They pay back a lot of energy. I can come to school in the morning grumpy or really stressed with lots of stuff hanging over my head. Then the kids will start coming in and all of a sudden I just perk up."

His first job out of the Humboldt State University credential program was at Alice Birney, and he's been there ever since. Located in Eureka's southwest side, one might expect Alice Birney to be poor in resources. But Blinn's classroom bristles with high-tech gear. There are four PCs, 11 wireless Mac laptops and a sophisticated large-screen interactive digital whiteboard.

But Blinn says that while grant funding for IT equipment is plentiful, the school is short on cash for other items. The whiteboard projector has yet to be installed properly, and the classroom is sometimes not vacuumed for three or four days due to tight maintenance budgets. "There's money specifically earmarked for technology and nothing else," says Blinn. "And there's not very much money for some other things."

Yet he's passionately proud of Alice Birney's accomplishments. "Because it is a lower-income school, the public perception is it's not necessarily a good school," says Blinn. "Yet our test scores are really good, really solid." And the API ranking system that accounts for the economic and educational levels of parents has given Alice Birney a 10, the highest score possible, for several years running.

Blinn gives some credit to the 2001 No Child Left Behind accountability law that has pressured schools to improve students" performance. "I don't think [the standards] have always been realistic, but at the same time I've been surprised at what we've been able to accomplish," he says. "I don't think we would have strived to do that without the push from No Child Left Behind."

This year, Blinn is gearing up to teach a new hands-on science curriculum from University of California Berkeley's Lawrence Hall of Science. "Science is one of my favorite subjects to teach, but I haven't done it for several years because there were dedicated teachers who taught it during our prep time," he says. "The district changed that so this year we have these new science kits."

He's also excited about ramping up an Accelerated Reader program, in which students read independently in class, choosing books from a library he has put together. "When I was first teaching, I was hesitant to devote a lot of time to independent reading," he says. "[Even though] studies say it's an important thing for kids, there were a lot who either weren't actually reading, or they'd read two pages of one book then read another book the next day."

With the Accelerated Reader program and computers in the classroom, he has students take computer-based quizzes on the books they've read to demonstrate their comprehension. "After the first month or so I can get 90 percent of kids really reading in a book of their choice," he says. "The goal I set for them is that each month they should have read one book and taken the quiz on it."

A poet and writer himself, Blinn also values personal storytelling and creates space for it in the classroom. "I have a lot of stock stories," he says. "I don't really plan when I'm going to tell them. Something will just take place that will cue me and I'll say, "That reminds me of a story." Then they become comfortable sharing their stories, and they know that I'll make time for them.

"It lets them know they're valued. I learn from them, they learn from each other and it creates a sense that there are kids in our class who know cool stuff."

Comments