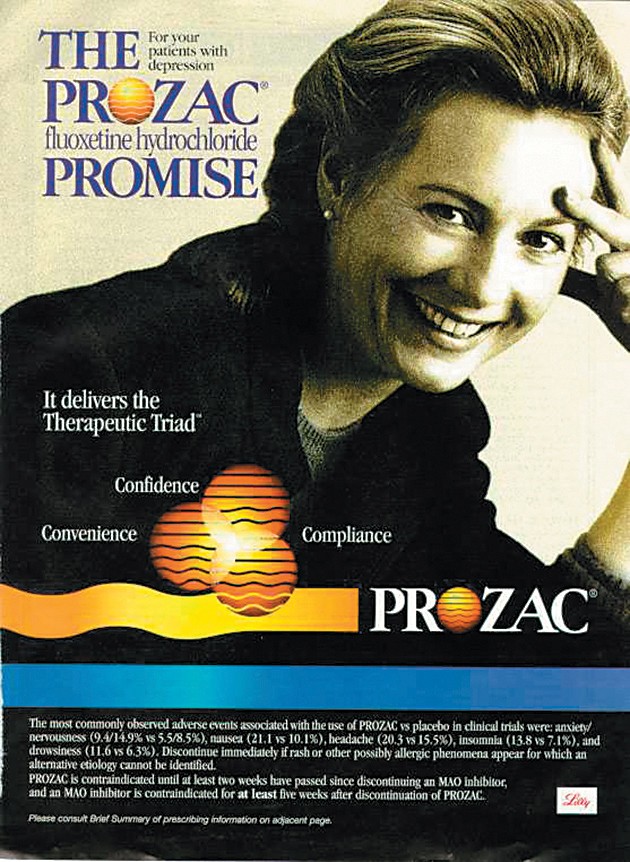

- Prozac advertisement

The theory that psychological problems are mainly caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain can be traced back 60 years, when French researchers accidentally discovered that Thorazine (chlorpromazine) dramatically improved the emotional behavior of institutionalized mental patients. Within a few years, the anti-psychotic properties of Thorazine and related drugs led to the trend in this country to reintegrate into society people who had previously been confined to mental hospitals ("deinstitutionalization").

Today, the "chemical imbalance" revolution is almost complete, as one in 10 Americans over the age of 6 take antidepressants. As Marcia Angell, former editor-in-chief of The New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in a controversial two-part essay in The New York Review of Books (June 23 and June 30, 2011), the pharmaceutical solution to psychological disorders has now become the norm, as more and more health professionals accept the theory that mental illness, including depression and anxiety, is essentially caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain.

The wholesale acceptance of this theory, by both the medical profession and the public, came with the introduction of Prozac (fluoxetine) in 1987. While Thorazine was thought to correct a deficiency of dopamine, Prozac was marketed as an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), designed to compensate for a presumed deficit of the neurotransmitter serotonin. (SSRIs block neurons from re-absorbing serotonin, leaving more of it available to activate adjacent neurons.) Because SSRIs alleviate depression, researchers speculated that depression was caused by too little serotonin in the brain.

Maybe. Or maybe not. Angell argues that by the same logic "one could argue that fevers are caused by too little aspirin." Perhaps SSRIs do something quite unrelated to neurotransmitters, and depression is unrelated to serotonin levels.

Whether the "chemical imbalance" theory is true or not, the real question is, Do antidepressants work better than placebos? Psychologist Irving Kirsch, one of the authors reviewed by Angell, used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain drug companies' records of their negative studies from the FDA. Unlike the positive results, negative results are normally not published. (Incredibly to this writer, negative results are considered proprietary and therefore confidential.) Taking both positive and negative results into consideration, Kirsch discovered that six popular drugs -- Prozac, Paxil, Zoloft, Celexa, Serzone, and Effexor -- scored unimpressively when compared with placebos. Yet, as Angell writes, "because the positive studies were extensively publicized, while the negative ones were hidden, the public and the medical profession came to believe that these drugs were highly effective antidepressants." It gets more surreal. When depressed patients were prescribed drugs such as opiates, sedatives, stimulants and even herbal remedies, Kirsch and others found their symptoms were relieved to about the same degree as with SSRI-type antidepressants.

Angell's essay was, as I say, controversial. One of the more curious responses, published as an opinion piece in the New York Times on July 9, came from Dr. Peter Kramer, author of the 1993 best-seller Listening to Prozac. This book-length endorsement of the drug (which predicted a Brave New World-style "cosmetic psychopharmacology" future for us all) probably did more than anything else to turn Americans on to SSRIs. In his Times piece, Kramer largely sidestepped the alarming questions posed by Angell and the three books she reviewed. Instead, he focused on the difficulties of distinguishing the effects of placebos from those of real drugs. And as he had done in his book, he relied largely on unconvincing anecdotal evidence to make his case.

What we do know about placebos is that they're not dangerous. However, even as increasing numbers of adults and children take powerful psychoactive drugs (because more of us are suffering?), researchers still have no clear handle on their potentially damaging long-term effects.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) gets depressed just thinking about antidepressants.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3