Rain fell steadily, muting the dark-green forested hills, the pasture and the tall redwoods. It fell gray-on-gray on the rocky river bar etched by ephemeral roads, and on the river itself, humping north a good 10 feet below the low-water bridge -- a narrow concrete-slab that spans half the river before it peters out on the gravel bar.

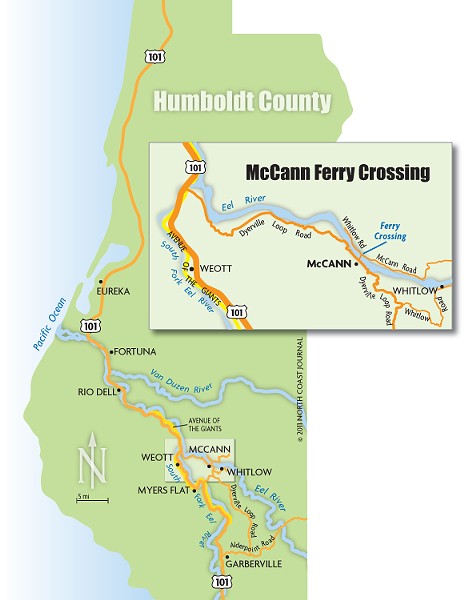

Just a few days later, the sun was back. It yellowed the forested hillside, blued the sky, brightened the spring pasture where several white horses grazed, and illuminated the handful of houses on the river's east shore - tiny McCann, a community on the main stem of the Eel River about six miles upstream from the confluence with the South Fork Eel.

But all that rainfall had plumped the river and now it sheeted over the bridge and engulfed the gravel ramp connecting it during low water to the river bar and the other side.

The bridge was no longer drivable.

Up on the west bank, in a clearing off the McCann Road, the ferryman leaned back in his white plastic chair and propped his feet on a large, rotted tree round. Behind him was a dirt parking lot with about 10 cars in it and a small wood rail bearing four mailboxes. Near his footrest, logs smoked and flared in an iron-ring pit. It was an hour before noon. Since 7 a.m. he'd been transporting McCann folk to and fro, including the four little Whitlow cousins who'd arrived just before 8 a.m. to cross the river with one mom who then drove them to Agnes J. Johnson Elementary School in Weott, several miles away. At 4 p.m. they'd be back to do the trip in reverse with the other mom.

The ferryman scanned the river for large debris lurking in the current. To his left, beyond a concrete container of firewood, McCann Creek -- a skinny, ruffled cascade -- sang on its descent to the Eel. To his right, the door of the small, corrugated metal shack stood wide open; inside was a wood stove, more firewood, life vests and a CB radio that began to crackle:

"It's Rex; I'm coming down," said a man's voice on the radio. "Gonna need a ride over."

The ferryman -- Johnny Rodriguez, former sawmill worker and a new member of the Humboldt County Public Works Department's boat crew - pushed up out of his chair and radioed back. Then he made his way down the path -- first a switchback of dirt steps, then a tangle of exposed tree roots alongside the creek mouth, then the skinny yellow tread-covered wood plank over the creek, and finally the dirt scrabble to where a small boat was tied to a tree. He put on his life vest, untied the boat, got in, fired up the motor, backed her up, swung her around and drove in a wide arc to the river bar on the opposite side. The hum of the motor blurred with the loud shhhhh of the river. A few minutes later, Rodriguez was guiding the boat back with Rex Whitlow aboard.

The U.S. Department of Transportation recently awarded Humboldt County $120,000 to improve the McCann Ferry, which - to the surprise of many, no doubt, if they even knew it existed - is still in operation. It's not a big ferry. Unlike the 34 other federal ferry grant recipients in the country, the McCann Ferry doesn't carry hordes of people or cars or heavy materials or anything like that. At most, the small, open-air skiff can carry two or three people at a time plus a few groceries.

Tom Mattson, the county's public works director, said they'll use the money to get a new boat and motor, put in an ADA-compliant ramp and launches, buy some safety equipment, and replace the tiny metal shed with an actual building that the ferry operator and passengers can hang out in on rainy days.

The McCann Ferry is the last of its size in California, and the remaining one of three such ferry services that used to ply the Eel River. At one time it was privately operated, including by Rex Whitlow's father and grandfather. But for the past 50 years the county has run the ferry. There's a county road on the other side, and the county is obliged to connect people to it. So when the river washes out the gravel ramp to the low-slung bridge and overtops it -- which happens several times each winter -- the ferry swings into action seven days a week, nine hours a day, except for Sundays and holidays when it runs for just four hours.

People have been getting across the Eel at this spot for, in the case of white settlers anyway, at least 150 years. Rex Whitlow's ancestor, Jesse Whitlow, came here in 1865 to raise livestock and buy land at what then was a stagecoach stop called Young's (the original McCann was on the other side of the river), according to a family history written by Rex's dad, Oral Whitlow Jr. Subsequent Whitlow generations and other families have ranched, harvested tan oak bark for tanneries, worked on the railroad, grown fruit, and worked in the mills that operated for a time on their side of the river.

McCann once was big enough to have a school and a store; both are gone now. Through the years, people have contrived all sorts of river conveyances - a seven-oar launch to haul workers across to the sawmill, a riverboat that traveled up and down between towns, a cable-strung gondola, homemade skiffs. And bridges.

Every bridge has been a bust. There have been floating bridges, said Bill White, supervisor of the county public works department's southern Humboldt road and boat crew. There have been two high-water bridges, spanning the river from bank to bank upstream where the river canyon is narrower - both washed out by floods. There have been several low-water bridges; the current one begins on the west side of the river and ends abruptly midway across, dangling above the river bar. It had been about 60 percent completed back when the big flood of 1964 hit, said White, 52, who began crossing to McCann to work in the woods with the Whitlows and other families when he was in high school. During the flood a mountain slumped into the river, adding tons of sediment and changing its configuration forever.

"The bridge should have been about 200 feet longer, which would put it higher on the river bar on the other side," White said.

In low water, county road crews pile the gravel up to make a ramp for cars to cross. When the river's high, the ramp washes out and has to be rebuilt once the water subsides. It sounds like a lot of bother. But Mattson, the public works director, said at an annual cost of $20,000 to $30,000, it's cost-effective to maintain the low-water bridge and run the ferry.

"The cost to build a high-water bridge would be about $10 million, because the bridge would have to be so high to get across such a wide area," he said.

About nine years ago, the county looked into extending the existing low-water bridge to a higher spot on the river bar to reduce the number of ferry days. To pay for it, the county proposed eliminating the ferry service to save up money. Some residents sued, not wanting to lose the ferry, and the county dropped the plan.

White said he'd like the county not to give up on a high-water bridge. Maybe they could convert the old railroad bridge upstream into a car bridge? It would require building new roads through private timberland and bridges over creeks -- financially and bureaucratically daunting.

"That's No. 1 on my list of things to do before I retire: to get a bridge built and get us out of the boat business," White said. "It's dangerous. You can't take the river too lightly, even in calm water situations."

In all the years the county has run the ferry, and in the days of the Whitlows before that, nobody has died crossing. They've died from other river mishaps. And once, in 2008 on an excursion upriver to show friends where his ancestors lived, Oral Whitlow Jr., who's 77 now, was almost sucked under the bridge in his own boat after it lost power. He was pulled free of the boat just as it went under.

Sure, there have been some interesting situations on the ferry, as Oral's wife, Lou, put it on the phone recently.

"The scariest one was when I had a boatman who - well, let's just say it was rough water," she said. "And I had my youngest son to take out. ... I had hold of him, we both had our life jackets on, and we went up into the crick where we had to land. But before we got there the boat tipped onto the riverside, because there's a big current there. I grabbed Ricky, his head and shoulders went under and part of my head did too. But I got him up."

Mostly though, crossing the river by boat is just a natural part of life in McCann, said Tami Whitlow, Rex's 27-year-old daughter, on a recent sunny day in between rainstorms. A petite woman in worn work clothes, Tami had stopped to natter with her dad and a neighbor after they'd all converged at the ferry. Rex, looking like John Muir with his bushy beard and wide-brimmed hat, agreed, but he recalled one stark moment from childhood:

"I once got packed across the river on a man's shoulders from that end to this side of the river when the river was over the top of the bridge," he said. "He was wearing hip boots. And we've lost a few boats down the river. Before bilge pumps, when it was raining, you'd come back to find your boat completely full of water. You had to check on it throughout the night."

But living by the dictate of the river is no stranger than raising and selling rabbit meat and peddling chicken eggs, like Tami did when she was a little kid. It's no odder than slaughtering hogs, building fences and cutting wood for hire, and selling homemade picnic tables - all things Tami does now for a living -- or canning homegrown vegetables and making wild blackberry jam, like she and her sister, Trisha, and their mother do. No more unusual than water-witching, which Rex does on the side for a local well driller -- though his main work is harvesting timber and running his and his parents' ranches. And Tami and Trisha got across the river just fine when it was time for their children to be born.

It can be inconvenient, though.

"If we get a break in the weather and can drive over, I'll go over and get a couple of bags of chicken feed and stock up on food and pig feed," Tami said. "If we don't get a break in the weather, we have to go by boat. Right now, I have four bags of pig feed in my truck in the parking lot. One by one I'll pack them across."

The big problem with the ferry, at least for kids, is school sports. Rex desperately wanted to play basketball after school when he was a kid, but there was only one boat in the family and the ferry stopped at 5 p.m. In high school, he fixed the problem: He got a job in town so he could stay overnight, going first to school, then work, then basketball, then back to work where he slept behind the counter.

Other than that, and the struggle to make a living, McCann is a good place to be, said Rex.

"There's that side of the river and there's this side of the river," he said. "I always tell people that come from the city that they should just leave that shit down there - you know, the kinds of things people hate one another for, and fight over. You know, 'This is mine and stay off of it,' all that kind of crap."

Tami said over here in McCann, people are welcome to trespass on their river bar.

"People come and bring their kids, and we don't have problems with that," she said.

"Yeah, we can get along with about anybody," said Rex.

Rex Whitlow crouched between the two white-rock-lined graves and broke off a piece of bright leafy plant. Held it to his nose. "Nope," he said. He stood and moved down the slope -- stooping, plucking, sniffing. Finally, he held a pretty sprig to his nose and shut his eyes. "That's lemon balm," he said.

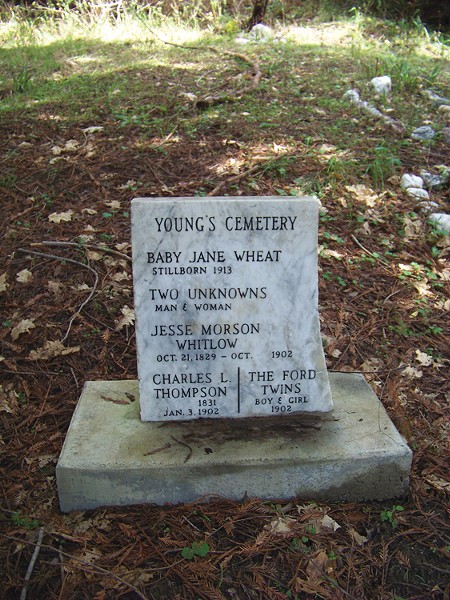

Whitlow helped his dad, Oral Whitlow Jr., restore this little cemetery a couple of years ago. Only seven people are buried here, their existence recorded on a fresh stone marker Oral made: "Baby Jane Wheat, Two Unknowns man and woman, Jesse Morson Whitlow, Charles L. Thompson, The Ford Twins boy and girl." Another new marker, on an actual grave, says "Mr. Thompson, first white man in McCann."

"My ancestor Jesse is buried in Mr. Thompson's dugout canoe right alongside of him," said Rex. The two men, livestock partners in life, died nine months apart in 1902.

Rex looked up the hillside, a troubled look on his face. "One day the neighbor here was logging and I heard a big CAT coming down the hillside. So I ran out here and I stopped that D8 right in its tracks, right here," he said, pointing at the edge of the cemetery. "That CAT almost tore this all up."

Rex walked back down the path to the ranch owned by him and his wife, Tracy. They've lived there for 33 of the 36 years they've been married. It's less than a hundred acres. Rex's mom and dad have 1,200 acres more, down considerably from the 16,000 acres the family used to own. Rex and Tracy bring in about $28,000 a year in timber, not much compared to the old days. They have 25 chickens, a dozen dogs, 14 horses and too many cats. And they've cut back a lot on their cattle stock.

As he neared his house, Rex's dozen dogs, staked at long-leash intervals around the upper perimeter of the yard, raised a full-bark chorus. These were his cattle dogs, Rex explained. If he let them loose, they'd herd everything in sight all night long.

Rex said he can't run his cattle wherever he wants to anymore. Investors have been buying up land around McCann and declaring it off limits.

"They threatened me with the livestock deputy," said Rex about one investor, the Rolling Meadows Ranch, based in Florida. "I had to sign an agreement. I have to keep my cattle off their property. And if they do get loose on there I have to remove them within 15 days or pay a fine."

He blames the land-grabbers for driving up land prices, which will hike his property taxes. The overgrown outdoor pot industry doesn't help matters, either.

"It's just fucking everything up" for cattle and timber families, he said. "I don't have the money to compete with that shit. And I don't want to grow pot."

A few days later by phone, Jim Redd, the Eureka-based land agent representing Rolling Meadows, said his client had listed 7,000 acres in the McCann area for $16.5 million. But then he took it off the market. He wouldn't say what his client wanted to do with the property. He did say that soon there would be an accessible road into it from another direction that would bypass the whole McCann river crossing.

Would the other McCann residents be allowed to use that road?

"No," Redd said.

Down on the river bar, Rebecca Bunker of Santa Rosa was just climbing out of the ferry. She was here to visit her fiance, Steve Mills. She dropped her life vest back into the orange bag that the ferry operator keeps on board. Her big brown dog leaped out to join her. She grabbed a six-pack of Downtown Brown in one hand and a grocery bag, towel and purse in the other, and headed to her truck. The keys were in the ignition. Down here on the river bar, when folks park to catch the ferry, they always leave their keys in the car. That way, if they're still out when the river rises, someone can go down and move them to higher ground.

It was getting cloudy again. Within days, the river would be swirling bank to bank, lapping at the driveways of McCann residents. Wood drifts bigger than the ferryboat -- uprooted trees, dislodged stumps - would careen like missiles in the current, banging against the bridge and perhaps lodging on top of it. And the forecast was for more rain. Which meant weeks more of ferry travel for the residents of McCann on the wily, wild Eel River.

Comments (14)

Showing 1-14 of 14