A local professor is fond of saying politics is essentially choosing who gets what, when, where and how. If that's the case, then the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors is in the process of deciding what its members will get, when they will get it and how they will get it when it's time for them to run for re-election as the board continues wrangling with a proposed campaign finance ordinance. In essence, the supervisors are setting the rules for how their re-election bids will be financed, which will dictate how much they have to spend on radio, television and newspaper advertising, lawn signs, paid campaign staff and just about every other aspect of their quest to retain public office.

The board has long been in the process of considering some type of campaign finance reform for county elections and recently assigned a subcommittee consisting of Fourth District Supervisor Virginia Bass and Fifth District Supervisor Ryan Sundberg to draft a proposed ordinance. But, apparently, First District Supervisor and Board Chair Rex Bohn got impatient, as he agendized the item for the supervisors' Sept. 9 meeting, proposing the board scrap the subcommittee and direct staff to come back with an ordinance loosely modeled after Sonoma County's.

At the meeting, the board's conversation meandered, wandering through the nuance of a complex set of laws and court rulings that govern such ordinances. Bohn, who said he figured it was time to force the issue because it's "slack time" in local elections, said he was looking for a way to "cap contributions so we can take outside interests out of the equation," later adding that those "big money donations" aren't representative of the community as a whole, yet have the power to shift elections.

Second District Supervisor Estelle Fennell essentially agreed, saying the public perception is that certain deep-pocketed groups and individuals hold undue sway over the process. "When you think about the general feeling that we want campaign finance reform, I think a lot of that reflects what we see on a national scale, especially when we hear about these gigantic political action committees and super PACs and the massive influence they have on national politics ... Of course, then people tend to bring that down to a local level and say, 'Oh, all that's happening here,' and I don't know that's the case," she said. "We need to give some kind of assurance that there's a level playing field."

Exactly what constitutes a level playing field and how to get there was the topic of more than an hour of debate by the board, which ultimately voted 4-1, with Third District Supervisor Mark Lovelace dissenting, to direct staff to craft an ordinance that prohibits candidates from accepting more than $1,500 from a single donor in a primary election and more than an additional $1,500 in the event of a runoff. While a $1,500 donation might seem like "big money" in a county with a median annual household income of $40,830, according to the U.S. Census — it is 3.7 percent of the median — it's clearly not by Bohn's definition, as he repeatedly referred to donations of $5,000, $10,000 and beyond as the ones he was seeking to prohibit.

In casting his "no vote," Lovelace said he preferred a $500 donation cap (like those in place in San Diego, San Francisco and Santa Clara counties) and a voluntary spending limit of $50,000, which would rein in overall spending and stop the trend of six-figure campaigns. His ideas got little traction among his colleagues.

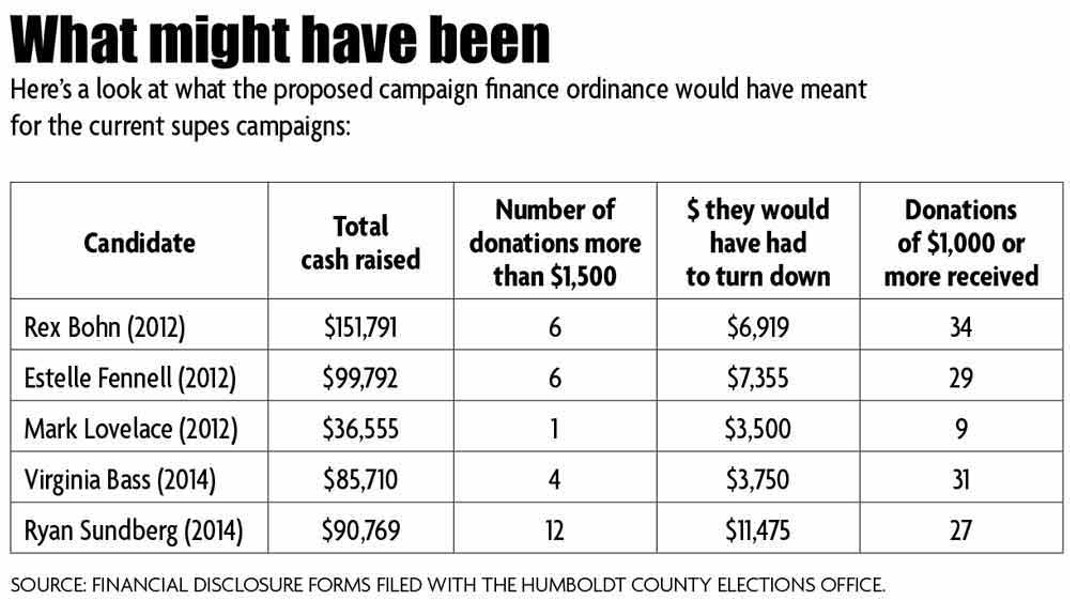

Staff is expected to bring back a proposed ordinance in the next few weeks, at which point supervisors said they will seek more public input and continue the discussion. In the meantime, the Journal decided to pore through some recent campaign finance disclosure forms to see how the proposed ordinance may have impacted recent supervisorial elections, had it been in place.

A few months ago, county voters re-elected Sundberg and Bass. In the Fifth District, Sundberg raised a total of $90,769 in cash donations to fend of challenger Sharon Latour, who culled together just $12,003 in cash donations. Sundberg received a total of 12 donations of more than $1,500 and, had the proposed ordinance been in place, would have had to forego $11,475 in contributions, 13 percent of the total amount he raised. Latour's balance would have remained unchanged, as she didn't receive a single donation that went over the proposed cap.

In the Fourth District, Bass received four donations of more than $1,500, and would have had to return 4 percent of the $85,710 in cash donations she received for the race. Her challenger, Chris Kerrigan, benefitted heavily from two large donations — $5,000 from Bill Pierson and $2,100 from Kenneth Miller — and, under the proposed ordinance, would have had to turn down $4,100 in donations, roughly 9 percent of his $45,544 total.

It's difficult to imagine the proposed ordinance having significantly affected the outcome of either race. Overall, it would have kept $19,325 out of two races that saw four candidates combine to raise more than $234,000.

There have been races, however, that would have been dramatically impacted by the proposed ordinance, most notably Bass' successful 2010 bid to unseat Bonnie Neely, a 24-year incumbent. If we apply the proposed rules to that contest, Neely would have had to return a whopping 48 percent of her fundraising total of $143,889. For her part, Bass would have had to refuse $10,100 in contributions, about 6 percent of her $173,475 total. Despite Neely's boost from a few big donors (she got $30,000 from Blue Lake Rancheria, $21,000 from Bill Pierson and $10,000 from a business based in Dana Point), Bass took 55 percent of the vote in the general election.

While it seems the proposed ordinance wouldn't have a sweeping impact on local elections — Neely-Bass and a few other races aside — a lower contribution cap could have some dramatic implications, as it's clear a few dozen donors are responsible for a huge amount of campaign funds.

For example, this year Sundberg took in $49,730 in contributions — 55 percent of his total haul — from 27 donors who each put down more than $1,000, a dollar amount the average Humboldt family would be hard-pressed to donate. Bass received 31 donations of $1,000 or more, accounting for 54 percent of her total cash contributions. Kerrigan and Latour each received four such donations, accounting for 21 and 37 percent of their totals, respectively.

For those keeping score at home and wondering about 2012: Bohn took in 34 donations of $1,000 or more (accounting for 35 percent of his total haul); Fennell recorded 29 (40 percent); and Lovelace listed nine (37 percent).

On Sept. 9, a majority of the board made clear that it isn't looking to overhaul campaign financing in Humboldt County, just to rein in the outliers. There was a lot of talk about leveling the playing field, of limiting the influence of special interests. "The whole idea was to get the big checks out," Bohn explained. "It's not to take anybody out of the process. It goes back to what it's supposed to be — the people's election."

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1