It's Dec. 8, and three members of California Cannabis Voice Humboldt are sitting in the Journal's Old Town office. There's a sense of urgency — and even a little desperation — as they explain how the group has grown from its inaugural meeting less than six months ago to push itself to the forefront of the 18-year-old conversation about how Humboldt County should regulate its largest industry.

In some ways it's been a tough week for California Cannabis Voice Humboldt. Copies of the group's draft outdoor marijuana cultivation ordinance started trickling out a couple of weeks before and have captured several local headlines, most of which the group feels have tilted negative, focusing on its ambitious timeline and concerns in the environmental community. What's missing from the conversation, they say, is just what is at stake.

"You thought the end of timber was bad?" asks Luke Bruner, CCVH's co-founder and treasurer. "Well, if we lose cannabis all we have left is meth."

"From an industry standpoint, the urgency comes from a need for survival," adds Patrick Murphy, the group's community outreach director in Willow Creek.

The way Bruner, Murphy and CCVH stakeholder Isaiah O'Donnell tell it, the legalization of recreational marijuana use is sure to hit California ballots in 2016 and be voted into law. Widespread trends in the industry, they say, suggest that change — likely to come with the state's first regulatory framework for growing and selling marijuana — will result in a limited number of permitted producers. Those permits are likely to end up in the hands of a few massive, large-scale growers, they say, pointing to examples in Colorado's burgeoning recreational weed market, Minnesota's medical model and elsewhere. The result, they say, will be that Humboldt County's 10,000 marijuana farms (CCVH's number) will be squeezed out of the newly regulated industry and, consequently, more than a quarter of the county economy will evaporate with them.

"We can't stress enough how big the consequences are," Bruner says. The sliver of hope the group has glommed onto is that whatever state regulatory framework emerges from California's legalization push ultimately does one of two things: gives preference to growers who have a documented history of being in compliance with local regulations, or grandfathers in functioning local ordinances.

Either way, they say, Humboldt County — which has largely been paralyzed with inaction on the regulation conversation — needs to move quickly by approving and adopting a large-scale outdoor marijuana ordinance that gives growers a chance to be compliant and move their operations completely aboveboard. That's why the group is working on an initiative ordinance, which state law says the group can take directly to county voters if the board of supervisors chooses not to enact it. It's a power play — a successful one — and it's making a host of stakeholders throughout the county more than nervous.

It's an effort that's also been very successful in taking the all-but-dormant conversation surrounding marijuana regulation and pushing it to the forefront of Humboldt County politics. But Bruner, O'Donnell and Murphy dismiss talk of any power play, saying this is a real response to a very urgent need. Large scale corporations are zeroing in on California's cannabis industry, they say, poised to wipe out small farmers permanently. It's up to Humboldt to flip the script that's played out elsewhere, unite and come up with a model that protects the little guy.

"The revolution starts here," Bruner says. And the clock, he says, is ticking. CCVH wants something on the books this spring, before the start of the outdoor growing season.

The principal guiding California's provisions allowing local citizens to pass initiative ordinances is a populist one. "The idea is when we have corrupt government or a government that's not acting in the best interest of the people, we need a way to go around them," explains Ryan Emenaker, a political science professor at College of the Redwoods. "It gives people the power to enact what we think is important, which is very much in line with democratic ideals."

But, the professor quickly adds, initiatives get complicated. "The advantage is that anyone can put forward a ballot initiative," he says. "The drawback is that anybody can put forward a ballot initiative."

The business of making laws and ordinances like one regulating Humboldt's marijuana industry — which a 2011 study conservatively estimated accounts for more than $400 million of the county's $1.6 billion economy — is easier said than done. Through traditional channels, these types of ordinances face a long road of committee input, legal review, public comment, California Environmental Quality Act review, planning commission review and public discussion by the county board of supervisors. The path can take years and, even if approved by the board, there's no guarantee the finished product will look anything like the original drafts. That's because the system is designed to find middle ground and to try to identify and address unintended consequences.

But with an initiative, the process is more direct. If you have something you want done, you simply draft an ordinance and get signatures from 15 percent of the county's registered voters. The ordinance would then come before the board, which would have three options: Adopt it as written, call a special election or order a staff report on the ordinance, which would have to be completed in 30 days, after which the board would have 10 days to approve the ordinance or put it before voters by calling a special election.

Less review means more room for error and a higher likelihood of unintended consequences, Emenaker says, pointing to the county's 2004 attempt at passing a ban on growing genetically modified organisms. That initiative, Emenaker says, wasn't properly vetted and contained a fatal flaw. By the time it showed up on ballots, Emenaker says, even its authors weren't supporting it. Despite the concept's widespread support, it would be a decade before proponents took a stab at another initiative, getting it passed in November. "There's a huge cost to getting these things wrong," Emenaker says.

Kathleen Lee, a political science lecturer at Humboldt State University, says it's also important to remember that citizen's initiatives can't be modified once they are passed except through another vote of the people, making it difficult for them to fix problems or adapt to changing situations. As an example, Lee points to 1996's Proposition 215, a purposefully vague initiative that essentially decriminalized marijuana in California for medical use but didn't specify any regulatory system. Few at the time imagined the scale and complexity of today's industry but subsequent efforts by state lawmakers to regulate the medical marijuana industry have been deemed unconstitutional because they restricted Proposition 215. The result is the industry's current state.

Back in the Journal offices, Bruner, O'Donnell and Murphy indicate there's not even universal agreement within CCVH that the initiative ordinance is the best path forward. Supervisor Mark Lovelace, they say, has indicated he'd be willing to take the issue up as an urgency ordinance of the board, which would allow it to go through an expedited public process. "I really think that's probably the better solution," Murphy says. But if that process stalls or gets bogged down, Murphy says CCV is prepared to go forward with the initiative. "The initiative process is not a weapon," Murphy says. But it is a tool that will remain on the table.

Ultimately, though, whether it's through an initiative or a board ordinance, Murphy says it's imperative that whatever regulatory system comes out of this process will have widespread buy-in from all stakeholders. It needs to be something that growers, environmentalists, cops and local government can stand behind — that's the only way it will be taken seriously by the state. But there have already been some bumps in the road.

For its first stakeholders meeting, CCVH invited a few dozen folks — environmentalists, growers and local officials — to tables decked out with Play-doh and Koosh balls and, later, a catered lunch. The process was supposed to be fun, foster creativity and collaboration. It got off to a good start, according to a handful of folks who attended, with much discussion of both the importance of cannabis to the county and its economy and the need to clean up cannabis' environmental footprint. Then, an environmentalist in the room asked about the 10,000-square-foot canopy allotment in some of CCVH's paperwork, contending the number was too high.

When the group convened again, the number had jumped to 20,000 square feet and many in the environmental community started to feel their input was being ignored. "At the second meeting, we were watching environmental stakeholders who'd been invited into the process get up and walk out of the room," says Hezekiah Allen, executive director of the Emerald Growers Association, a local marijuana trade association focusing its efforts on lobbying at the state level.

The initiative's first drafts did little to foster unity but offer a rough overview of the group's framework. The CCVH proposal calls for marijuana to become a principally permitted use on parcels larger than 5 acres, including on timber production zone lands, meaning growing marijuana is allowed without any need for a discretionary permit as long as one follows the rules. Growing activities would be licensed by the Humboldt County Agricultural Commissioner's Office as long as growers demonstrate that they would: abide by state law, employ "best management practices," agree to random site visits (the ordinance doesn't state by whom), pay all applicable fees (it doesn't specify what the fees would be or how — or by whom — they would be determined), agree not to use chemical fertilizers and rodenticides not approved by the commissioner, register with the California Employment Development Department and be in compliance with state labor laws, and agree to have random samples of their crops tested for pesticides, herbicides and "other biologic or chemical contaminations" (it doesn't specify who would do the testing). Further, the ordinance states that all applicants should have a "cultivation and operations plan approved by the commissioner and state and county agencies, as appropriate, that meets or exceeds all minimum legal standards for water storage and use, water conservation, drainage, erosion control, runoff, pest control, watershed protection, [and] protection of habitat." The draft doesn't say when such approval would be appropriate or exactly what minimum legal standards would apply, given that there are no existing industry specific standards.

The commissioner's office would then declare applicants who provide all the aforementioned documentation and show themselves to be in compliance as "certified Humboldt County growers," a designation that would be valid for one year and renewable following annual inspections of the applicants' cultivation site(s) and certification of laboratory test results for their most recent crops (tests will be conducted at a commissioner-approved laboratory for the presence of pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, mold, fungus or other contaminants). Testing is expensive, however, and the ordinance doesn't mention who will pay for it or where it will be done.

As should be expected in any effort to bring a large-scale, under-the-table industry into a regulatory system, the plan outlined in the ordinance includes some logistical challenges before even getting to the hot-button issues that dominate the marijuana cultivation debate. First, there is the fact that this would represent a massive increase in duties for the agricultural commissioner's office, which currently has six employees and oversaw some 300 certified farms in 2012, the last year for which numbers are available. CCVH estimates there are 10,000 marijuana farmers in the county, a number that would represent about 9 percent of Humboldt's adult population, according to U.S. Census figures.

Agricultural Commissioner Jeff Dolf declined to comment on the proposed ordinance in an email to the Journal, but did say he's in discussions with board members about "what form a commissioner's office cannabis cultivation program could take, and what resources would be needed by the commissioner's office to operate a regulatory program for cannabis."

Looking through the draft ordinance, California Department of Fish and Wildlife environmental scientist Scott Bauer says he's also not sure how his department would deal with the influx of permit applications. The department has been practically begging growers for years to come in and get their water uses licensed, Bauer says, to little avail. But if all came in at once it would be overwhelming, he says, adding that the department would likely have to come up with some kind of programmatic permitting that allows folks to get their permits by pledging to follow the rules. But even that new program, Bauer says, would likely necessitate an additional full-time environmental scientist position to do nothing but permit grow operations and conduct follow-up compliance checks.

But those growing pains are to be expected with any ordinance seeking to regulate marijuana. It seems likely CCV's proposal will ultimately sink or swim on three key issues: allowable canopy size, growing on TPZ lands and revenue.

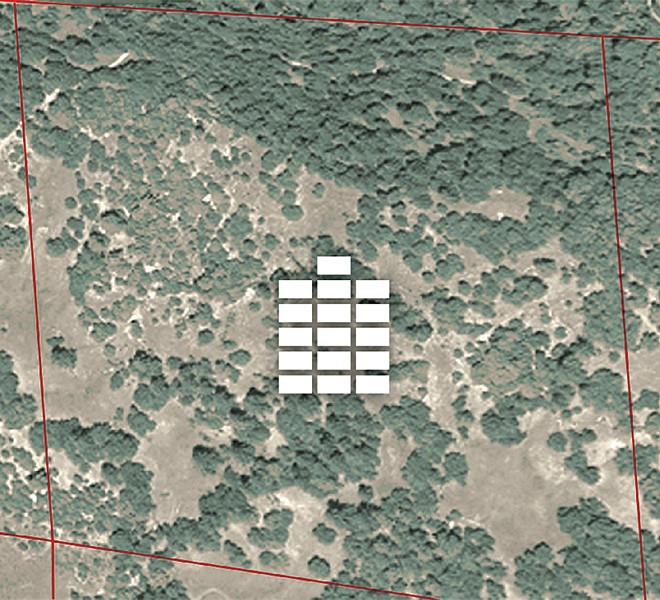

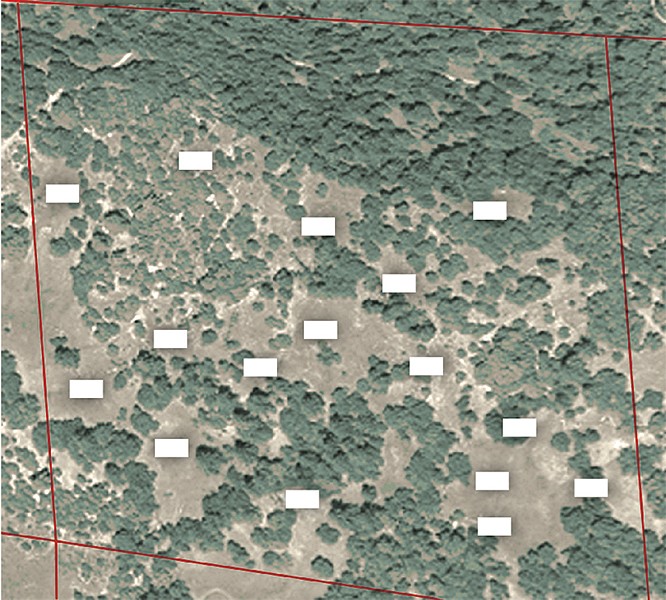

As the bumps in the process thus far attest, the question of allowable canopy sizes is undoubtedly the largest separation between growers and environmentalists. Bauer, the fish and wildlife scientist, has spent years with the department studying the impacts of marijuana grows and water diversions on salmon-bearing streams. In that process, he and the department have put together aerial watershed maps identifying growing operations and estimating canopy sizes.

Bauer says the department recently completed a map of the Mad River watershed, and found about 160 grow operations with an average canopy size of 2,300 square feet, which he says fits with the rough averages he's found elsewhere in the county. CCV's latest draft of the ordinance contains a range of canopy size options, from 1 percent of total parcel size to specific caps that go from a 1,750-foot canopy on parcels between 5 and 10 acres to 60,000 square feet for parcels larger than 40 acres. The range is huge, and unacceptable for many environmental groups.

Dan Ehresman, executive director of the Northcoast Environmental Center, says these numbers — especially on the upper end — are a "huge concern," adding that "what CCV is proposing is unequivocally the highest level of principally-permitted operations" anywhere in the state.

For Bauer, water impacts are of chief concern. From a strict diversion standpoint, he says a system that requires growers to store water in wet winter months and forbids them from pulling water during the summer may accommodate some of these larger canopy sizes without diminishing river flows in the summer. However, Bauer says that's only part of the equation, as it's the partnership of water flow and water quality that creates sustainable habitats. It's impossible to know the impacts to water quality of fertilizer and sediment runoffs from these grows without further study, the type CEQA would provide, he says. "That's what we would want to analyze," he says, adding that CEQA could also help determine if different standards are necessary for different watersheds.

Murphy, CCVH's community outreach director in Willow Creek, says environmental groups have to realize that some growers are pressing for an ordinance that allows up to 2 principally permitted acres of canopy. The quandary CCVH faces, he says, is that a canopy cap that's too stringent will result in zero compliance and zero buy in from growers. One that's too large, meanwhile, will get no support from environmental groups and possibly even open the door to the large corporations the group is concerned will take over the industry. What everyone has to realize, he says, is that 2-acre and 1,000-square-foot caps are both nonstarters. "These two numbers are equally unrealistic," he says.

Bruner, O'Donnell and Murphy say CCVH's next draft will begin to zero in on a middle ground to the canopy question, but all think 10,000 square feet is reasonable, as it would allow someone to grow 99 10-foot-by-10-foot plants.

The other question looming is the ultimate legal status of growing on timber production zone land, or lands that have been set aside for the preservation of timber. These lands are reportedly rife with growing activity and CCVH feels marijuana cultivation should be an acceptable compatible use that helps preserve the bulk of them as forest lands. But environmental groups worry this could lead to the further fragmentation of the forests, especially considering these parcels are generally large and would accommodate larger canopy sizes under a tiered approach.

Bauer says it's important to remember a garden's canopy isn't its only impact, or the only part of an operation that would lead to deforestation and erosion issues. A garden has to be serviced by roads, and the ordinance would require on-site storage and processing facilities, as well as permit temporary labor camps. All of that has impacts, Bauer says.

Even most environmentalists concede that most potential impacts can be adequately mitigated with proper regulation and oversight, but that takes a hefty and steady revenue stream. The fact is California has plenty of laws on the books to deal with the environmental crimes being carried out throughout Humboldt's watersheds, where streams are being sucked dry and sites are being trashed. The problem is funding adequate enforcement.

This is a place where environmental groups and others watching say CCVH's ordinance is troublingly quiet, including only a brief mention of "applicable fees," without going into any detail of what those would be or how they would be determined. "That's the crucial component of anything that we put forward," says Ehresman, "whether it's taxes or fees, we have to have some funding mechanism for regulation, oversight and enforcement."

This isn't lost on the CCVH trio, as all talk about the need to fund proper oversight and even the county's need for additional revenue to invest in schools, infrastructure and law enforcement. A more detailed accounting of where revenue will come from, they say, will be in the next draft.

Dressed in jeans and a button-up shirt, Murphy smiles as he concedes that getting Humboldt County to present a united front on this issue is going to be tricky. He says CCVH has already made some mistakes, but he pledges that the group is intent on getting this done. The only way to do that, he says, is to make sure everyone has a seat at the table.

But he, Bruner and O'Donnell are also quick to say it would be foolish for anyone to step into that process expecting a single ordinance to instantly correct the lawlessness that has been allowed to fester for decades. Ultimately, O'Donnell says getting an ordinance passed that gets 5 percent of growers to comply and move their operations into legitimacy in the first year would be a win.

The hope then is that legitimacy would be incentivized, with licensed growers being allowed to enter into sanctioned marijuana auctions and other things that help them band together and demand a better price for their product. Targeted busts that hold those out of compliance accountable while leaving compliant farmers' plants in the ground could further spike an interest in coming into compliance. And the more the industry tips toward compliance, the more growers following the rules would be willing to turn in those who are not, they say.

"The key is compliance over time," Bruner says. "Somewhere in there is a critical mass, and the tipping point will come."

Humboldt County grows some of the finest cannabis in the world, they say, and that tipping point could ultimately lead to a booming niche marijuana market, the type that would make the county what Napa is to wine. They picture a boutique industry with tasting shops, a steady stream of tourists coming to sample the latest crops and tours catering to international marijuana connoisseurs.

But there's a long road ahead and, at least on CCVH's schedule, little time to get there. And, for better or for worse, it's this upstart group, that Murphy concedes is "learning on the fly," that is driving the conversation. Bruner says none of them asked to be in this position, noting that the board of supervisors had an opportunity four years ago to tackle this very issue but walked away from it. Now, they say, it's time to get it done or risk watching Humboldt County's largest industry die, taking the local economy down with it.

But others say the stakes are too high — for the environment and the economy — to hitch this wagon to an initiative crafted largely behind closed doors. They say this needs to be studied, vetted and argued in public to make sure everyone is included and there are no unintended consequences.

"I just don't think an initiative is the correct process for a highly complicated land use decision," says Natalynne DeLapp, executive director of the Environmental Protection Information Center.

On the phone from Sacramento, where he's lobbying on behalf of the Emerald Growers Association to influence any state regulatory bill passed this year, Hezekiah Allen agrees. Allen says CCV has done an "incredible" job of getting people engaged and talking about the issue, but he says an ordinance ultimately needs to go through CEQA and be vetted in public through a community dialogue.

That way, no matter what happens, the revolution will be televised.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3