A couple of weeks ago, one of the many small intergovernmental chat shops that hammer out Humboldt County public policy behind the scenes met for the final time. This particular working group had been meeting for over a year. Its goal was to study ways to build a hiking and biking trail between Eureka and Arcata -- the “Bay Trail.” People had been talking about such a trail for many years. Now they were all at the table: representatives from the cities of Eureka and Arcata, the county of Humboldt, the Humboldt County Association of Governments, the Humboldt Bay Harbor District. Bicycle and trail advocacy groups, as well as other interested parties, were invited to attend. The general public was not.

At this meeting, which took place at a small conference center in Arcata’s Redwood Park, the working group would receive the fruits of its labor. Several months ago, it had found the money to commission a consulting firm called Alta Planning, which specializes in trail development, to study different ways to route and build the Bay Trail. Now the consultants would present their initial findings.

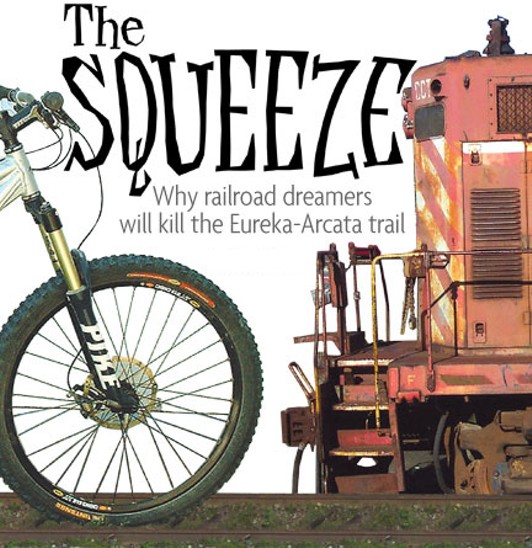

The Bay Trail is a difficult proposition, because there simply isn’t much room to build in the most logical corridor -- on the bay side of Highway 101. At some points, there is only a small sliver of land between the freeway and the water, and much of that land is taken up by a corridor owned by another public agency, the North Coast Railroad Authority. In one way or another, the trail would, in all likelihood, have to cross the authority’s right-of-way, which has not been used for almost 10 years.

The consultants presented their initial findings. One option, which involved Caltrans altering the highway to some degree, would cost around $45 million. Another option, which would rebuild the railroad’s degraded infrastructural so that it could accommodate trains and pedestrians, would cost around $31 million. A third option -- removing the railroad for the time being and putting the trail in its place -- would cost $14.5 million. That last figure would include the cost of putting the tracks back when the railroad was ready to run again.

According to several people at the meeting, Mike Wilson, who represents the Arcata area on the Harbor District, questioned the consultant about the final option. What if the costs of putting the tracks back were taken out of the equation? What if that were accounted for separately? The consultant wasn’t certain, but he estimated that the trail in that case would cost only about $5 million.

Humboldt County Supervisor John Woolley, who sits on the NCRA’s board of directors, argued that it didn’t make much sense to look at the cheap option. Who would give money to build a trail when the trail would have to be rolled up as soon as rail service to Humboldt County is restored? The railroad authority’s forecast was that trains would be rolling down local tracks in just four years’ time -- by 2011.

The mention of this date so soon in the future seemed to agitate Wilson. “No one in this room believes that,” he said. At which point a stony silence filled the air.

The North Coast Railroad Authority, a public agency, an arm of the state of California, has been dinking around with the old Humboldt-to-Bay Area railroad line for 15 years now, consuming tens of millions of dollars in public funds and accomplishing very little. It’s been six years since the NCRA has run any trains at all, nearly a decade since the last train made it to Humboldt County.

But hope springs eternal in the railroad world, and the NCRA and its supporters, armed with a sheaf of fanciful dates and numbers -- trains to Humboldt by 2011! -- have secured themselves a solid place in the hearts and minds of local policymakers, from members of local city councils all the way up to our elected representatives in Sacramento and Washington. And the authority has received many boosts of late. For the first time in years its coffers have been filled, thanks to infusions of public money. It’s been a long time since its prospects have looked so bright.

If that’s the case, though, it’s only because the authority has so far been able to ignore all the many problems raised by its drive to restore the rails. That blessed state will not last forever. But it will certainly last long enough for the authority to accomplish one thing -- dragging the Bay Trail into a bureaucratic quagmire almost as impossible as its own.

No one disagrees that the Bay Trail, whatever form it takes, is a difficult project. If the trail is ever built, someone -- some agency -- will take on the financial obligation of maintaining it, which is not completely insignificant. “The funding is a challenge, any way you slice it,” said Jennifer Rice of the Redwood Community Action Agency last week. “It’s going to require a lot of creativity and commitment to make it happen.”

Still, it would be hard to find anyone who would argue that the trail would be a whole lot more doable if the initial costs were in the $5 million range, rather than the $30 million range. But people like Rice, who six years ago led a comprehensive study on the potential for a new trail system in the Humboldt Bay area, have to accept that the political reality, as evidenced by Woolley’s comments at the working group meeting: The North Coast Railroad Authority is not going to hand over the keys to its publicly owned right-of-way, however painful that may be.

“We’re open to all options, but we’re just really concerned,” said Chris Rall of Green Wheels, an alternative transportation advocacy group based in Arcata, last week. “At the time when we were more optimistic, we thought maybe it would cost twice as much to put the trail beside the rail. But now it’s looking more like five times as much. And it concerns us that it’s going to take a long time to find the money to build this sort of trail.”

At the same time, though, the trail would bring immediate benefits to Humboldt County. According to Alta Planning’s initial report, the trail would be a tourist draw as well as an alternate form of transportation down the Eureka-Arcata corridor, where no good options for bicycles or pedestrians exist. The consultants estimated that the trail would give a direct $3.8 million boost to the local economy.

From a regional perspective, a Bay Trail would fill in a large gap of the California Coastal Trail, an incomplete project with solid support from the California Coastal Conservancy and other agencies. It could link up to the Arcata-to-Westhaven Hammond Trail in the north, providing a bicycle route from Eureka all the way to Moonstone Beach. It could someday link up with the still-unfinished Annie and Mary Trail, which will run from Arcata to Blue Lake. If the railroad were ever to give up its quest to reestablish train service and turn the tracks over to trail usage, as has been done in many other “railbanking” projects around the country, people could realistically dream about a system of paths that would run from Scotia north, and around Humboldt Bay to Fairhaven.

But the railroad authority, which took over the struggling old Northwestern Pacific line in 1992 by an act of the state legislature, is maintaining the position it has held ever since the Federal Railroad Administration shut down the line in 1998. It plans to reopen the railroad, including the geologically unstable Eel River Canyon section of the line that links the tracks in northern Humboldt to the south end of the railroad, which runs from Willits south to the Bay Area. (See “Going Nowhere,” May 29, 2003.) No one knows how much reopening that particular stretch -- which is home to perennial slides, slip-outs and tunnel failure -- will cost; estimates range from $150 million up, and no one is quite sure where the money will come from.

Still, the authority will soon be commissioning an environmental impact report for the reopening of the Eel River Canyon, and looking to develop a business plan that will make rail service all the way to Humboldt Bay an economically feasible undertaking. And that’s when its real problems will begin.

The North Coast Railroad Authority is in an awkward bind. First of all, given the decline of the timber industry, it has to invent freight to ship in order to justify its existence.

?hen the NCRA is in Sacramento, it has to demonstrate that this potential freight is so massive that it will be possible to financially overcome the line’s chronic, costly infrastructure problems, especially in the Eel River Canyon. So in February of last year, it wrote up a “strategic plan” to present to the California Transportation Commission. The goal of the strategic plan was to convince the CTC to release some $43 million in funds that had been allocated to the authority in 2000, right before the California budget collapsed. When the budget crisis hit, the NCRA fell to the bottom of the CTC’s priorities. It didn’t help that the commission had previously raised serious questions about the authority’s accounting methods, earning it a designation as a “high-risk grantee.” But the worst of the crisis had largely passed by last year, so in March 2006 the authority attended the CTC’s monthly meeting armed with its new plan, and there it made its pitch.

The railroad’s last comprehensive financial forecast, written by a consulting firm called PB Ports and Marine in 2002, showed that the railroad most likely stood to lose around $4 million per year, even after the line was brought back into service. But the NCRA brought new numbers to the CTC. The new strategic plan now said that the railroad could ship 6 million tons of crushed rock per year -- a little over 11 tons per minute, 24 hours a day, 365 days per year -- from a moribund quarry partially owned by the authority in the heart of the Eel River Canyon, at Island Mountain. The plan noted that this would result in 40,000 rail cars of material per year, or 110 cars per day, every day of the week. The quarrying would result in a $20 million annual revenue stream for the authority.

But there was more. In addition, the authority said that it stood to gain $130 million per year from a revamped shipping operation at the Port of Humboldt Bay (see this week’s “Town Dandy”). According to “one estimate,” the railroad could ship 1,000 freight containers per day, five days a week, from a bustling new container port on the Samoa peninsula. Shippers would pay $1,000 per container to have their goods transported from dockside to the national rail network. While the CTC had questions, the presentation did the trick. It began releasing money to the NCRA in dribs and drabs, allowing it to begin work restoring the south end of the line and planning for operations on the north end.

But that’s where the second of the railroad’s troubles came into play. Suddenly the authority had to convince the public that it didn’t really mean any of it. That’s the second and more difficult half of its bind.

When the February 2006 strategic plan was released to the public, some people took an interest. The first group to respond was the watershed watchdog organization known as Friends of the Eel, based in Garberville. When the group’s executive director, Nadananda, heard of plans for a massive new quarry on the banks of the federally designated Wild and Scenic Eel River, she sounded the alarm, railing against the plan in the group’s newsletter and notifying environmental groups in the Bay Area (see “Hear that train a-comin,” June 8, 2006) .

What’s more, it caused some port-watchers to lift their eyebrows and wonder what shipper would pay a $1 million-per-day premium to move goods from a purely hypothetical container facility on Humboldt Bay, down the long, slow tracks of the Eel River Canyon, a several-day journey from here to the Bay Area, only to arrive at one of the greatest natural harbors on Earth. Yes, the trade between China and the West Coast of the United States is booming and many West Coast ports are at capacity, but is that really the most sensible option, from a business perspective? And does the environmentally conscious constituency around Humboldt Bay really want a big new container port, with all of its associated impacts in and around the bay?

After the CTC loosened its purse strings, and after such opposition began to raise its head, the NCRA released several updates to its strategic plan, including one in February of this year. These updates are far more limited in scope. The February 2007 update focuses mainly on a proposed timeline of work. Specific operations, such as the Island Mountain quarry and the Port of Humboldt Bay, are not mentioned. With the CTC funding in hand, the NCRA now insists that any discussion of specific work programs is premature.

“For anybody who wants to paint a picture, I see where it would be a problem,” said Mitch Stogner, the NCRA’s executive director, from his office in Ukiah Monday. “As a factual matter, it’s not a problem. As a factual matter, what’s on the table is our February ’07 strategic plan. What was said prior to that, based on NCRA’s efforts to get the CTC to release funding, is not what’s on the table.”

However, as noted above, the February 2007 document is an “update” to the earlier plan, not a brand-new plan of its own. It complements the earlier plan; it doesn’t contradict it. It simply lays out a schedule by which the railroad will reopen in stages, culminating with the 2011 return to Humboldt Bay.

One useful way to look at the rail-trail standoff is generationally. The most prominent people working for a Bay Trail -- Mike Wilson, Jennifer Rice, Chris Rall -- are relatively young. All of them are in their 30s, and all of them have roots in Arcata. They all went to Humboldt State. They’re all politically active. Rice was the university’s “woman of the year” when she was a student there, and was active in student government. Wilson represents the city on the Harbor District. Rall and his colleagues in Green Wheels, an organization born at HSU, are playing a larger role in debates over transportation issues.

On the other side of the aisle, the coalition backing the railroad is an odd one, made up of a number of disparate factions -- lots of government people, some industry people, some labor people, some grown men who simply never outgrew their boyish fascination with big, powerful machines. But the most important bloc behind the railroad, at least in Humboldt County, has been the up-from-hippie generation that came to power in Arcata 30-odd years ago, and which has held on to power ever since. This generation -- which includes Woolley, former state Senator Wes Chesbro and former Assemblyman Dan Hauser, who served as NCRA’s executive director for several years in the ’90s -- made its bones in the fight to protect Arcata from the impacts of a freeway bypass, and, especially, in the battle to build the Arcata Marsh, a sewage treatment facility grounded in low-impact technology that also reclaimed a big chunk of land for wildlife habitat.

It’s not easy to explain how this generation, with its impeccable environmental credentials, with its reputation for getting things done, came to find itself in the curious position it now occupies as regards the railroad. Not only do the leading members of the Marsh Generation not oppose a massive new rock quarry on the banks of the Eel River, some of them, at least, are counting on its success. Not only do they not oppose the industrialization of Humboldt Bay, either on the grounds of practicality or desirability, some of them, at least, are out stumping for a plan that -- taken at face value -- would theoretically send some 20 diesel-spewing trains per day, each of them pulling 50 cars, through the very heart of the marsh itself, to say nothing of Eureka’s Old Town. This is the priority. The Bay Trail, a project that would complement the marsh perfectly, must come second.

Speaking from Sacramento, where he was lobbying the legislature on railroad-related matters (among other things), Woolley said last week that perhaps the younger genera tion simply wasn’t used to seeing trains in Humboldt County, and was therefore unnecessarily nervous about the prospect.

“We all have been around during the time when the train was running, and also when it hasn’t been,” he said of himself and his cohort. “We’re also aware of environmental and economic factors in every decision we make.”

He added that when the time comes, the state-mandated process for addressing environmental concerns on the north end of the line -- the EIR the authority will eventually undertake -- will provide ample opportunity for decision-makers and the public to scrutinize the impact of the quarry and the harbor, and on freight passage around the bay.

Woolley also said that passenger service around Humboldt County may someday be feasible, despite this area’s sparse, scattered population. Given rising fuel costs, who knows what could happen in 15 or 20 years? “But the key to that is keeping the railroad as a viable option,” he said.

In the meanwhile, and until proven otherwise, he and other members of the Marsh Generation are sticking solidly to their efforts to reopen the railroad. When Chris Rall wrote up his impressions of the final meeting of the trails working group for the Arcata Eye, Dan Hauser, now retired from his last job as Arcata’s city manager, was quick to quash his hopes.

“It would require an act of the Legislature and the Governor’s signature to modify that NCRA mandate,” Hauser wrote in a letter to the paper. “I strongly suggest that Mr. Rall and the other trail advocates forget about removing the rail and concentrate on the other alternatives.”

Someday, perhaps far in the future, if and when the railroad ever starts running trains, Hauser’s words may prove prophetic. Since the NCRA has for most of its life existed solely in the subjunctive tense, there has been little political opposition to it. Taxpayers’ groups have occasionally decried the authority as a waste of public dollars, but the powers-that-be in Sacramento have not heeded their call.

Now the political equation seems to be shifting, in such a way that the possibility of legislative action to change the NCRA’s mandate is not entirely unthinkable. Even in inaction, the NCRA is starting to get in the way of things. The Bay Trail is one example, though one that is unlikely to spark any significant statewide revolt.

More problematically, the inconsistencies in the NCRA’s plans are just starting to be felt at the south end of the line, in Sonoma and Marin counties. For many years, the citizens of those counties have been looking at developing intercity passenger service along the same rail corridor that the NCRA will use to ship freight. The public agency charged with developing such a service -- called Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit (SMART) -- will be placing a sales tax measure to fund it on the ballot in 2008. (The measure will require a 2/3 vote for passage; a similar proposal was narrowly defeated in 2006.) SMART is especially popular in Sonoma County, where severe traffic congestion is a grim fact of life.

But when people in Marin County began to take notice of the NCRA’s freight projections along the same corridor, some of them grew concerned. SMART had published an environmental impact report for its project in June 2006, a few months after the NCRA had published its strategic plan. But the section of the SMART document that addressed the impact of NCRA freight service on its proposed operations seemed to differ significantly from what the authority was telling state government. According to SMART, the NCRA planned to run only six 12-car trains per week, coming and going. This wasn’t only manifestly insufficient to account for all the freight the authority anticipated from the quarry and the port; it didn’t seem to be enough to account for all the other traffic the authority hoped to ship purely on the south end of the line. In fact, in the strategic plan the authority envisioned hauling 12 cars of garbage per day out of Sonoma County, in addition to other south end traffic. This inconsistency led Marin County to claim two seats on the NCRA board of directors earlier this year -- seats that had been carved out by the agency long ago, but which Marin had hitherto shown no interest in.

On June 20 of this year, the City of Novato wrote to SMART to ask the agency to supplement its environmental impact report with updated figures for NCRA freight operations. In a letter to SMART dated June 20, Novato City Manager Daniel E. Keen wrote that Novato was “extremely concerned” about the impacts -- noise, traffic, pollution -- of large-scale freight operations. The city had recently learned that the NCRA had near-term plans to run much larger trains on the tracks that run through Novato, Keen wrote -- 32 trains per week, some of them up to 60 cars in length. These figures came directly from a memo that Stogner wrote to the NCRA board of directors at the end of May. But three weeks later, when Stogner wrote to SMART to address the confusion, he explained that it would be unnecessary for the transit agency to update its environmental impact report: “The only difference is that we now estimate six 15-car trains per week rather than our original estimate of six 12-car trains per week.” Any other operations were purely speculative, Stogner wrote.

Novato City Councilmember Jim Leland is one of the two Marin representatives recently appointed to the board of the NCRA. He said last week that his goal in joining the NCRA board was to bring some clarity to the project. “When the number dances back and forth between six trains a week and 30, those are big swings,” he said. “That doesn’t fly down here in Marin County. All these shenanigans run the risk of turning some environmental organizations against the whole thing.” (And those 30 trains per week don’t even begin to take into account any of the massive rock and container freight that will supposedly be coming down through Novato from north of Willits -- by 2011, theoretically.)

Leland noted that the Novato City Council is slated to address the matter again on July 19, and that there is a public forum on the matter scheduled for July 31. He said that his constituents are starting to demand answers. And some are starting to think beyond freight service, he added. If there were no freight operations at all, the thinking goes, SMART might be able to use the corridor to develop an electric-powered light rail system rather than the diesel engines it now proposes to use.

“There’s a whole range of views starting to surface now that there’s a visible community dialog about freight and passenger service,” Leland said.

For the time being , though, the railroad can proceed as if such issues didn’t exist. An uprising in the populous, wealthy places at the south end; a lawsuit over the Island Mountain quarry; the chance that international shippers might not consider Humboldt Bay such an attractive port, or that Humboldt County citizens wouldn’t want such a port anyway -- they all fall into the same category. As long as the railroad’s plans continue to exist only in the realm of speculation, there are no downsides. And so state and federal money can continue to flow to the authority, and the contradictions looming within the NCRA’s plans can be safely ignored. Out of sight, out of mind -- at least for the time being, until the authority develops a solid plan for the north end of the line.

But that should be plenty of time to bog down any momentum the Bay Trail has developed. After receiving the preliminary Alta Planning report, Woolley and Arcata City Councilmember Mark Wheetley met with local Caltrans officials on a fact-finding mission. Their goal was to lay the groundwork for an expansion of Bay Trail options -- to recast the Alta report as the beginning of a discussion, rather than a plan of action. What they are pushing for now is an expanded look at trail options, a look that will consider placing the Bay Trail on the east side of Highway 101 and across the bridge, down the Samoa Peninsula.

“I’m saying we can continue to look,” said Wheetley, who worked on the Marsh project as an HSU student. “You don’t build the $40 million option when you haven’t looked at the $10 million one.”

In fact, the east side and Samoa options were looked at in the process of developing the 2001 Bay Trail feasibility study, the one that Jennifer Rice worked on. At the time, it was determined that there were serious constraints to both options. On the Samoa side, for instance, it would be difficult and expensive to retrofit the numerous bridges that cross various sloughs. But last week Rice acknowledged that the Alta study was limited to studying only the west side of Highway 101, mostly because of the limited amount of funds available to pay the consultants.

In any event, even without additional studies, the tra il can probably safely be considered a dead letter for the time being. A (roughly) $30 million project is orders of magnitude more difficult than a (roughly) $5 million project, and the political grasp of the railroad backers is such that the latter option -- the conversion of the fallow right-of-way to productive use -- will be promptly round-filed as soon as the final Alta Planning report is released, which should be sometime this month.

Asked to gaze into his crystal ball last week, Mike Buettner, a member of an advocacy group called Trails Trust of Humboldt Bay who was at the meeting when Woolley and Wilson clashed, didn’t find much cause for optimism -- neither for the railroad, nor for the Bay Trail.

“They’ll sidetrack the discussion and talk about running it along the east side or through Samoa, and they’ll talk about it for years,” Buettner said. “The trail won’t get done, and the train won’t come back.”

Comments