This summer, a nonprofit outfit called Ecotrust will be going around the North Coast asking fishermen to reveal their favorite ocean fishing spots. The interviews are part of a process to determine where to establish marine protected areas (MPAs) in state waters -- from shore to three nautical miles out. California is mandated by the 1999 Marine Life Protection Act to design a network of such areas, and it's been tackling the task region by region.

Ecotrust, which held introductory meetings in Eureka and Fort Bragg this week and will hold another one in Crescent City next Thursday, is gathering socioeconomic data for the state. Data from seafloor mapping, currently underway, also will be used. And, in each region, local stakeholders work with the state to propose areas for protection. A science advisory team vets the proposals, and a state-appointed Blue Ribbon Task Force decides which ones get forwarded to the state Fish and Game Commission, which makes the final determination.

So far, two regions have undergone the process -- the central coast, around Monterey, and the north central coast, which includes the southern portion of Mendocino's Point Arena. The south coast is underway, and now the north coast is on deck. The San Francisco area will be last.

When it's all said and done, there will be an interconnected network of these MPAs, some of which will be off limits to all fishing and marine product extraction, and others which allow restricted fishing.

To some folks here in the North Coast region, from Alder Creek near Point Arena to the border with Oregon, this thing's like some kind of slow-motion tsunami -- they've seen it coming for a long time, they don't like it, but damned if they can get out of its way.

Others see it as a big, speeding, wayward ship of good intentions that needs some local pilotage to slow it down and get it back on course.

And yet others view it with confident optimism, and hope.

Last Friday was a blustery day. And even though the fish were out there -- hordes of them, according to recent fishing reports, plying the jaggy rocks and underwater canyons off Cape Mendocino and the rocky zone near Trinidad -- the fishermen knew better. It wasn't a day to be on the ocean. Better to dock the boat in its slip in port or on a trailer, curbside, in town, and just stay in.

"With this wind and rain," said one old salt to another that morning outside Englund Marine Supply Co. on Eureka's waterfront, "everyone's probably home playing cards and drinking."

But actually it seemed like everybody was coming down to Englund Marine. It was the first day of the fishing and boat supply store's giant annual tent sale, and the goodies-laden tables and racks in the parking lot lured a steady stream of commercial and sport fishers -- the latter bunch including some folks who looked like they'd gone AWOL from the office to not miss the big event.

People loaded up on new poles and navigation systems and lures and line and hardware and life vests and myriad other essentials. But a random poll of the shoppers revealed a pessimism toward the MLPA that seemed at odds with the forward-looking vibe of the shopping spree.

"I'm dead against it," said a cranky guy, who wouldn't give his name, as he hauled his loot to his pickup. "The whole protection pendulum has swung out of bounds."

Eureka dentist Michael Holland, a sport fisherman, stood under the tent by a display of reels talking to Tim Klassen, who runs a charter boat out of Woodley Island Marina. Both men are members of the Humboldt Area Saltwater Anglers, a group that formed a year ago to give fishermen a bigger voice in the MLPA process and the political arena in general. Holland, 60, who has fished all his life, has followed the implementation of the MLPA in other regions with trepidation.

"They don't heed the advice of the fishermen," he said. "And I'm disappointed by the underlying assumption [of the Act] that we're going to fish these areas to extinction. We feel here on the North Coast that the weather, and the ocean conditions, self-limit how much fishing can be done. But that's not taken into consideration."

Inside the store, Eric Justesen, 42, studied a shelf stocked with colorful squid-shaped lures -- good for catching bottomfish -- while his 8-year-old son, Leland, crammed little lures into the mouths of bigger lures and made monster noises. Justesen, who has a bachelor's degree in marine biology but couldn't find work in his field, is self-employed and fishes to feed his family.

"I fish once or twice a week, depending on the weather, the regulations, the season -- all the things that keep us from fishing," he said somewhat bitterly. He said he's "disgusted" with the state's push for reserves. "They want to close things down and take it all away."

At the counter, Mike Zamboni was buying a new prop and hydraulic steering. Zamboni fishes commercially out of Trinidad with a small hook-and-line boat, and sells his catch -- rockfish, crab, salmon -- to Murphy's Market.

"Probably have to buy a bigger boat so I can fish outside the closure areas," he grumbled.

Big commercial fishing boats, which can go farther out into federal waters after big fish like salmon, won't be affected by the state MPAs. But Zamboni fears the 20-some small hook-and-line commercial fishermen in the region, like him, will be -- along with commercial crabbers, and the half-dozen charter boats that take sport fishers out on excursions, and the thousands of sport fishermen who launch their little boats out of local marinas.

That in turn could hurt the towns near the marinas, he said. "Most of the tourism in this area is directly or indirectly related to fishing."

There've been MPAs of one form or another in the state for a hundred years. There's even a small, two-square-mile MPA at Punta Gorda, about midway between Shelter Cove and Cape Mendocino. But up until the recent push under the state MLPA, the reserves have been a scant hodgepodge with no scientific or administrative rhyme or reason, said Melissa Miller-Henson last week by phone.

Miller-Henson is the program manager for the MLPA Initiative -- the public-private collaboration charged with implementing the act. It's composed of the state Department of Fish and Game, the state Natural Resources Agency, and Resource Legacy Fund Foundation, which receives money from five private foundations. The Initiative is the state's third attempt to implement the act. The first attempt, right after the act passed, floundered because it failed to include local stakeholders in the process. In the second attempt, the state ran out of money.

The MLPA directs the state to redesign the MPA system by creating an ecosystem-based network of reserves that are each big enough to contain a representative selection of different habitats found within state waters. And each must have at least one other reserve near enough that fish and larvae can move between them -- the state-appointed science advisory team suggests they be no more than 30 to 60 miles apart. Some of the reserves are to be no-take zones. Others will allow restricted fishing (or other marine product extraction). The act aims to protect biodiversity, create undisturbed breeding zones, restore depleted fisheries and provide better research possibilities.

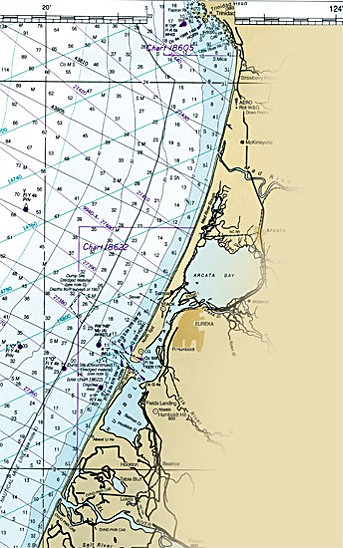

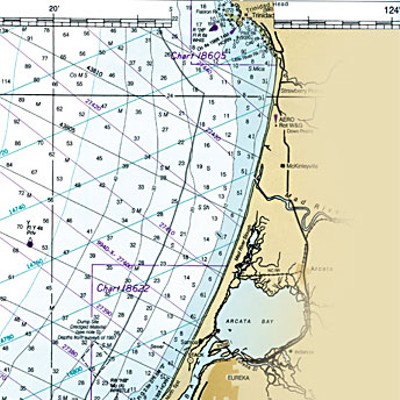

Local fishermen say the best places to sport fish on the North Coast are around Cape Mendocino, Trinidad and Redding Rock. These rocky areas are separated by long stretches of largely sandy-bottomed habitat. Fishermen fear that the size, habitat and distance specifications for the protected areas could mean entire beloved rocky areas being locked in preserves.

And there really isn't anywhere else to go to get rockfish nearby. Cape Mendocino, the best spot by many accounts, is 25 miles south of Eureka's port and 35 miles north of Shelter Cove's -- barely close enough for a small sport boat to get to, fish, and be home by dark.

"If they closed Cape Mendocino, my business would probably fall about 80 percent," said Phil Glenn, skipper of the charter sport fishing boat Shellback, docked at Woodley Island, last week over the phone. "Unless they open salmon season again."

It's easy to see why fishermen are testy. Salmon season -- which normally would be in full-swing right now -- is shut down this year, and was closed or severely restricted in previous years, because of low river runs (sometimes in the Sacramento, other times in the Klamath). Rockfish season has shrunk to three months on the North Coast (compared to 10 months in Southern California), and fishermen are not allowed to fish beyond 20 fathoms (120 feet), in order to protect the prized, brightly colored yelloweye.

Plus, they've been hearing reports from the MLPA Initiative process in other regions: that MPAs on the Central Coast took away 40 percent of their best sport fishing grounds; that a well-connected, conservation-minded seaweed farmer around Point Arena has had his prime collecting grounds locked up in a no-take MPA; and more.

But Miller-Henson said nothing's set in stone with the MLPA, other than the fact it must be implemented. Even the size of the MPAs can vary from what the state science team suggests. Decisions on where and how big the MPAs should be depend largely on the involvement of individual stakeholders in each community, she said.

"I have to say, I become a little annoyed at those people who are doing everything possible to spread this message that MLPA ignores local voices," Miller-Henson said. "That's as far from the truth as could possibly be."

She said the anti-MLPA rhetoric has ramped up in recent months, especially in Northern California, spurred by folks who've been involved in other regions.

"I had one fisherman say flat out to my face, three years ago, 'My job over the next few years is to make your life miserable and to stop this process,'" she said. "I'm still getting e-mails from him."

She said some of the naysayers actually showed up at the initial workshops in their particular regions, but then "they walked away and chose not to participate."

"Our intent is not to prohibit sustainable fisheries," she said. "The seaweed guy? He came to one of our workshops, and then didn't participate. As a result, one of the areas he utilizes is proposed for an MPA. If he'd participated, probably our stakeholders would have recommended it as a conservation area that specifically allows his activity."

Recently the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District's Director of Conservation, Adam Wagschal -- who's coordinating a local MLPA workgroup -- drafted a letter to California Natural Resources Agency Secretary Mike Chrisman. The letter is circulating among North Coast government entities, tribes, fishermen, environmentalists and port authorities for signatures before it gets sent off.

It notes a number of concerns: It says there is massive data gap on the North Coast, making it impossible to create truly science-based MPAs here; that money hasn't been set aside to fund actual management of the MPAs; that the actual price tag of implementation alone has soared to nearly $60 million (the initial cost was estimated at $250,000); that the Blue Ribbon Task Force's members know little to nothing about fisheries; that the process might not consider existing constraints on fishing and possible future ones, such as wave energy projects; and that the process threatens to take away the Pomo Indians' traditional shellfish harvest on the North Central Coast. "Our North Coast Region has numerous indigenous Tribes that still reside in their ancestral territories and we find this precedent unacceptable," he writes of this latter concern.

The data gap was confirmed last year after researchers from Humboldt State University and the local firm H.T. Harvey & Associates, with funding from the Resource Legacy Fund Foundation, compiled a database of all of the existing available science that might be used in creation of the North Coast's MPAs. The end result -- called the North Coast Marine Information System -- is a searchable database of documents and maps.

But you'll find mostly stuff about the heavily studied Humboldt Bay subregion, notes the scientists' report on the database. There is far less information for Klamath River, Point St. George, Fort Bragg and Shelter Cove -- and zero data for the Sinkyone. And, while there are tons of data on seagrass beds, estuaries and lagoons, and intertidal habitats, there's very little on habitats like kelp forests, rocky reefs, underwater pinnacles, submarine canyons and rocks and islands.

Wagschal said the district tried to secure a grant to fill some of these data gaps -- to do stock assessments, for instance, and to study the effects of fishing on species composition.

It didn't get the money. Now, the district wants to meet with Chrisman to discuss delaying the MLPA process. Because it isn't the MPAs they're necessarily opposed to, but how they're being decided.

"We're really eager to work on this stuff, to start getting the data," said Wagschal, who has done research in the Channel Islands in relation to MPAs. "And we want the state to take a step back. The sky's not falling. The fishing's not so heavy up here."

Another criticism is that the process isn't considering other impacts to the ocean -- such as pollution, oil drilling or other human endeavors. Nor does it call for studying what happens outside marine protected areas -- do those areas get overfished? Do fish from the MPAs really flow out into the non-protected areas and help replenish them?

But the MLPA Initiative's Melissa Miller-Henson says the act isn't intended as a catch-all measure -- that there are other processes for dealing with other impacts. And the act specifies the use of "the best readily available" information. "Clearly the legislature did not intend for someone to go out and spend tens of millions dollars on new research," she said. "But complementary to that is another key element of the act: It also requires adaptive management, in recognition that we don't know it all yet. So, over time, as we do learn more and more, we need to be sure we adaptively manage that ecosystem."

She added that the entire process is transparent and open -- through meetings, which are also Webcast live and archived on line along with proposals and maps.

Out at Woodley Island, on a recent sunny weekday evening, Tim Klassen, skipper of the charter boat Reel Steel, was scrubbing down the boat after an all-day excursion with five Austrians. The Austrians, who were up at the café drinking beer, had paid $700 for the charter boat, plus another hundred for Klassen to clean and filet their fish, and a tip.

In a year, Klassen figures he pulls in around $25,000. Not great, but for a retired welder -- he served the pulp mills for 18 years -- it's a nice semi-retirement gig. And a necessary one, in this economy, he said.

Klassen's been following the MLPA process. He said he's not against marine protected areas -- he knows a lot of fishermen who aren't -- but he, like many others, worries the process is not backed by enough data. Take yelloweye, for instance -- Klassen believes the fish is more abundant than regulators think it is, but there's no sound data to prove it. He's also not so sure that the North Coast needs protecting. The fisheries are already regulated heavily, for one.

"And every trip I make for rockfish, I'm easily limited out," he said. "There are lots of large fish out there, and lots and lots of fish."

Conservation-minded stakeholders point out that the MLPA isn't just about restoring depleted fisheries.

Jennifer Savage (who writes for the Journal, we must disclose) recently became the North Coast Coordinator for the Ocean Conservancy, a nonprofit that's helping implement the MPAs from a conservation perspective. She said just because the North Coast might not have some of the troubles that other areas do, that's no reason to balk at the notion of creating protected areas.

"It's also about preservation," she said. "These are like underwater state parks. So, if you're looking at a grove of old-growth redwoods and saying, wow, these are really special and beautiful and there's all this intricate ecosystem happening here, with all the critters and birds -- you don't necessarily wait till it's clearcut to protect it. You set it aside as a special place."

Savage said she really hopes people give the process a chance. Pete Nichols, with Humboldt Baykeeper, likewise said he hopes the disparate North Coast stakeholders will come together in the process. He's forming a conservation coalition to work on a conservation-minded MPA proposal. But he's also participating in the harbor district and fishermen's working group, and although he hasn't signed that group's letter to Chrisman, he said he shares a number of its concerns.

"I do think we on the North Coast are unique," he said. "We don't have the fishing pressure of other regions."

The main thing is, it's coming. And you can't run away from it. Well, you can, but it won't help anyone. Even Steve Fosmark, who lived through the process down in Monterey and came out of it pretty bitter -- he lost some crab and swordfish grounds, and watched some prawn fishermen go out of business -- says North Coast folks better speak up. Fosmark was en route to Oregon to go tuna fishing last Friday and stopped in Humboldt Bay to catch some anchovies for bait. He also stopped in at the big sale at Englund Marine.

"One of the things about our area, we didn't have a lot of participation," he said. "I recommend these guys here make ’em listen.

If you want to get involved, the next North Coast Local Interest MPA Workgroup meeting is Monday, June 29, at 3 p.m. at the Humboldt Bay Aquatic Center in Eureka.

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5