- By Jim Woodring / Dan Clowes

- Weathercraft / Wilson

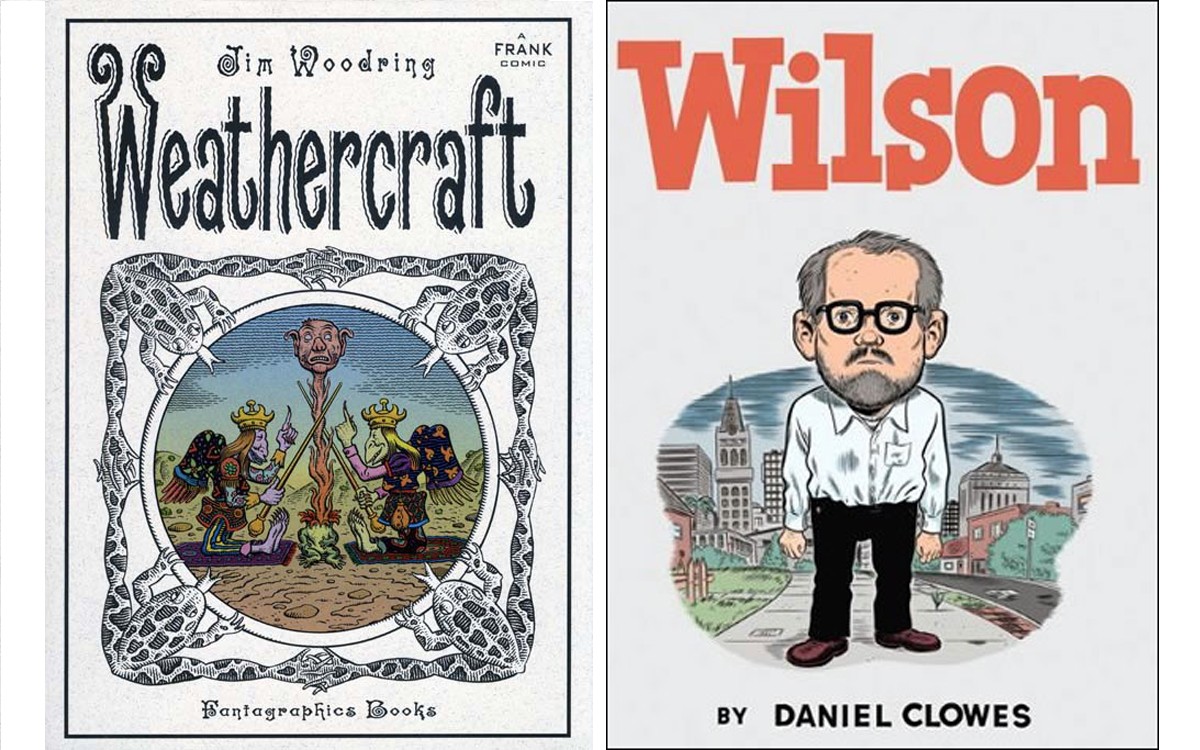

Weathercraft - By Jim Woodring - Fantagraphics Books

Wilson - By Dan Clowes - Drawn and Quarterly

Dan Clowes and Jim Woodring are both idiosyncratic graphic artists and storytellers, although I bet they wouldn't mind too much if you called them cartoonists. They both have roots in much earlier forms of comics, and don't have much use for what passes for the current mainstream in the medium, but they have little else in common. Their latest graphic novels provide a chance to see two very different versions of the state of the art.

In Weathercraft, Woodring draws from high and low: the hellish dreamscapes of Hieronymus Bosch, the fertile cosmic imaginings of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, and the seething, scruffy, sometimes threatening vaudeville of early Fleischer Brothers cartoons. He has a densely meticulous pen-and-ink style, and his wordless storytelling makes the tale that much more dreamlike (and difficult to summarize).

His characters are larger than life: the innocent Frank, the vulgar tortured Manhog, and the trickster god Whim are all iconic in a way unique to the medium of comics. The overused term surrealism fully applies to Woodring's work as it does to few others today. If it seems that he's transcribing episodes directly from his subconscious, it's his attention to craft that keeps the story from self-indulgence. In Weathercraft, Woodring has imagined a weird tale of mythic slapstick that recalls the best comics of the past, but also creates something singular and new.

If Weathercraft is comics as pure visual poetry, Dan Clowes' Wilson is verbal and prosaic, reigning in the extravagance and goofball humor of some of his earlier work in favor of astringent character analysis with a jaded tone similar to his book Ghost World.

His protagonist, Wilson, is reminiscent of one of Jules Feiffer's neurotics, though drained of any political context. Wilson is adrift and self absorbed -- the atomized man. Whether blathering to someone at a coffee shop or stuck in a jail cell, he's oblivious to those around him. He marries, and gets divorced, reconnects with his long-lost daughter, but the other characters hardly register -- they're strictly foils for Wilson's rants and insensitivity. The few times Wilson does reach out to someone, it's so foreign to his nature that the effort inevitably ends in awkward disaster.

There's always been a nihilistic undercurrent to Clowes' work, and Wilson's blind, sometimes cruel selfishness and sarcasm does not wear well for the length of the book. Though Wilson does seem to attain a bit of self-awareness at the end, it doesn't fully succeed either as black comedy, or as tragedy. Wilson as a character is ultimately a hollow man, and though that might have been Clowes' intention, the book still seems a step backward.

Comments