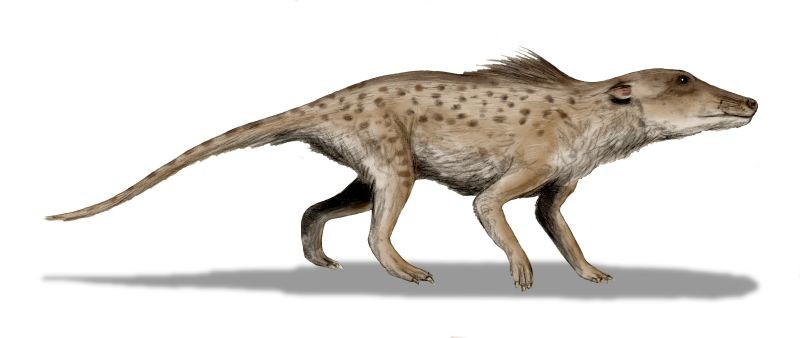

- Wikipedia/Nobu Tamura

- Pakicetus inachus, whale ancestor from the Early Eocene of Pakistan.

It just looked wrong. As the 45-foot mother whale circled and circled again by the Klamath bridge long after her calf had returned to the ocean, looking like any anxious parent, all I could think was, "Whales don't belong in rivers!" However, it wasn't always so. Fifty million years ago the earliest whales lived in freshwater habitats. We know this because the ratio of heavy-to-light oxygen (O18 to O16) found in their skeletal remains, especially teeth, decreases with the age of the skeletons. Since the O18 to O16 ratio is greater in seawater than in freshwater, whales must have inhabited a freshwater environment as a way station between their origins on land and the oceans they now call home.

Whales, or cetacea, are mammals: warm-blooded vertebrates that bear live young and nurse from mammary glands. Pioneering English naturalist John Ray was the first to propose the mammal designation 400 years ago, based on whales' similarity to terrestrial mammals. In the first edition of The Origin of Species (1859), Charles Darwin agreed with him, speculating that whales evolved from bears. (He removed this bad guess in later editions.) The earliest known cetacean fossil, looking more dog-like than bear-like, is Pakicetus - that is, "whale from Pakistan," honoring the site where the first specimen was found some 30 years ago, on what was once the shoreline of the Tethys Sea. Remnants of that ancient ocean include today's Mediterranean, Black, Caspian and Aral seas.

Dating back to at least 50 million years ago, Pakicetus resembled a 3-foot-long, 50-pound semi-aquatic hound (see illustration) whose diet probably included fish. Prior to the Cretaceous mass extinctions of 65 million years ago, land creatures that ventured into water risked being eaten by plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs and other marine reptiles. With those predators out of the way (thanks to an errant asteroid), the scene was set for mammals such as Pakicetus to radiate into newly vacated environments, including shallow seas of the Eocene Epoch which began 56 million years ago.

By 40 million years ago, the pressures of evolution had resulted in fully aquatic descendents of Pakicetus, ocean-dwelling, deep-diving whales. In the case of filter-feeding baleen whales (mysticeti) such as "our" Klamath gray, the two terrestrial nostrils at the tips of their snouts evolved into twin blowholes on top of their skulls. Toothed whales (odontoceti) such as sperm and killer whales, plus dolphins and porpoises, have a single blowhole. (The "nostrils" of whale embryos all start off at the tips of their snouts and move back during gestation in a classic example of the once-popular but now largely discredited theory of "ontogeny reflecting phylogeny," i.e. embryonic development mimicking evolution.) Betraying their mammalian ancestry, whales propel themselves with an up-and-down motion of their rear flukes, more akin to the movement of a running dog than a snaky fish. And whales steer themselves with their pectoral flippers, i.e. forelimbs, which look eerily like five-digit human hands in x-rays, again reflecting our common pedigree.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) is keeping all his digits firmly crossed for a happy ending to the tale of the Klamath whale.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2