Editor's Note: This is the first in a two-part series looking at addiction on the North Coast. While this story analyzes theories of addiction and its causes, the second part will look at efforts to combat the epidemic in Humboldt County and the barriers that stand in their way.

It's your mom, who started using painkillers after knee surgery and now can't do a day without them. It's your friend's boyfriend, the one who lost his license after the third DUI. It's your little cousin, who used to spend the night when his parents were fighting and now is in and out of jail. If you live in Humboldt County, odds are you know someone struggling with addiction. And the odds are also strong that they will die from their addiction. Over the past three years, more people have died from drug-and alcohol related deaths than all other causes of accidental death (drowning, falling, fires) combined.

"It's across the board," says Chief Deputy Coroner Ernie Stewart. "It doesn't matter which race, religion, way of life. Humboldt County is being overrun with illicit drugs, and it's getting worse in all facets."

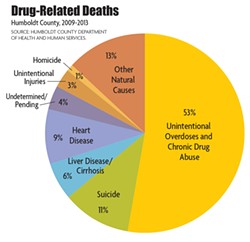

Stewart's report on accidental deaths is grim, laced with vignettes of lives cut short. February 2013: A 23-year-old man, highly intoxicated, aspirates on his own vomit. April 2014: A woman, 25, dies of combined ketamine and alcohol toxicity. March 2015: A man, 59, overdoses on methamphetamine. According to the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services, rates of drug-related deaths between 2008 and 2012 were three times higher in Humboldt than the California state average. Out of California's 58 counties, we come in a dismal second for drug-related deaths, beating out only Lake County. Of those deaths, the majority (53 percent) are due to unintentional overdoses or chronic drug use.

The numbers only tell part of how drugs and alcohol abuse impact our local roads, legal system, hospitals, tax spending and daily lives. Drugs and alcohol were a factor in 19 of the 23 traffic fatalities that have taken place so far this year. We rank fifth in the state for hepatitis C infections and fourth for suicide. One-third of the estimated 1,319 people living homeless in Humboldt report substance abuse disorders (a gross underestimate, some say). In 2012 more prescriptions were written for opiates than there are patients in the county. Also in that year, almost a quarter of all arrests made in Humboldt County were for drunk in public charges.

The impact of addiction is far-reaching, profound and complex, but its diagnosis is less quantifiable. To many, it's not even definable. Is addiction a brain disease, a series of choices, a moral defect or the product of a faltering social contract? How do we know when a person is an addict? Is it when their behavior becomes troubling? Is it the day they take their first drink and begin the slow spiral into dysfunction? Is it the moment they decide to admit defeat? While your average Humboldt resident may have strong opinions about addiction-related issues such as crime and homelessness, we lack a unified language and a unified approach to the problem. And as it turns out, we're not alone. Scientists and treatment professionals are similarly divided on the best way to diagnose and treat addiction.

The Moral Model

Once upon a time, the answer was simple. If you couldn't put down the bottle or the pipe, it was because you were morally weak and determined to sin. There was no acknowledgement of a genetic or chemical component to addiction. Those affected were shunned and subsequently unlikely to be honest about their afflictions. Because addiction was considered a moral failing, efforts to combat it were largely taken up by religious groups.

One of the earliest local mentions of a moral model is chronicled in W.W. Elliott's 1881 History of Humboldt County:

"The Good Templars in Humboldt County are banded together for the purpose of combatting the fell-destroyer — intoxicating liquors — together with all its concomitant baleful evils and influences. Lodges are flourishing in all parts of the county, but we were not able to obtain reports from the organizations."

- Submitted Photo

- Mike Goldsby, who recently retired after 30 years with the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services.

Mike Goldsby, who recently retired after 30 years with the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services and also teaches in the College of the Redwoods Addiction Studies program, has witnessed a gamut of approaches toward the problem.

Goldsby started his career in the 1970s as an advocate for alcoholics going through the court system. Back then, his clients were called "public inebriates."

"It's not a politically correct term now," says Goldsby. "They were trying to find a proper term for 'bums' or 'drunks.' Some were homeless."

Goldsby says that Eureka's Old Town at the time was "wild" — full of run-down buildings, dockworkers and taverns. Teenagers would cruise down Second Street on Sunday morning and watch alcoholics scrabble for pennies thrown from their cars. Societal understanding of alcoholism was slowly moving away from the moral model, aided by the example of First Lady Betty Ford, who went public with her own story of addiction and recovery in 1978.

But when Goldsby joined the county administrative office for alcohol and other drugs in 1984, the Reagan-era policy of "Just Say No" was in full effect. Federal dollars largely poured into incarceration rather than treatment. Refusal to legalize needle exchange contributed to the spread of AIDS and other diseases. The media resounded with stories of "crack babies" while students learned about drugs from the D.A.R.E. program. Studies of both D.A.R.E. and the "Just Say No" approach have since concluded that these programs were ineffective.

"It doesn't relate to the actual experience of having a compulsive issue," says Goldsby. "It oversimplified addiction, left the compulsive factor out of it. Nobody wakes up in the morning and decides that they're going to be a heroin addict."

Despite advances in science, psychology and treatment, a moral understanding of addiction still has deep roots in the public conscience.

"It makes me feel really sad every time I see a bumper sticker that says 'Kill the Tweekers,'" says Goldsby. "No one would have a 'Kill the Drunks.' If we reduce stigma it doesn't mean we're condoning use."

The Medical Model

A tenet of the moral model is that addicts choose to be addicts and that they lack the willpower to improve their lives.

- Photo by Linda Stansberry

- Alcohol and Drug Care Services Coordinator Dale Ward

"If only it was that simple," says Dale Ward, reaching for the pack of cigarettes in the breast pocket of his neat button-down shirt. Ward has been clean for 19 years and working with addicts in Humboldt County for most of that time, through the Mobile Medical Program, at local rehabs and in his clean and sober houses. Once "unemployable," he now coordinates substance abuse programs for Eureka Community Health. He says his clients represent a spectrum of ages, backgrounds and legal histories.

In the mid-1990s, when Ward was referred to a 12-step group by his probation officer after a lengthy bout with methamphetamine addiction, treatment of addiction was entering a phase of increased professionalism. Ward was still in early recovery when he attended classes at College of the Redwoods, mostly, he says, to learn more about himself. He was hired as a counselor in his fourth semester. While it used to be common for treatment programs to employ untrained former addicts, formal education and certification were becoming more common by the time Ward entered school. And while incarceration rates for non-violent drug offenses were still high, policy was shifting to reflect what science had suggested for decades: Addicts are ill rather than bad.

In 2000, the Journal of the American Medical Association formally proposed that addiction should be treated as a chronic medical illness, recognizing there is strong evidence supporting that addiction is a medical issue rather than a moral failing. Brain scans of addicts reveal a link between neurochemistry and drug use. Specifically, drugs (including alcohol) stimulate the mesolimbic pathway of the human brain, also known as the reward pathway. This portion of the brain is responsible for mood regulation and the administration of dopamine, the chemical that makes us feel happy. Addiction essentially hijacks the mechanism that controls our moods. Repeated use leads to tolerance, meaning that more and more of the original substance is necessary to achieve the same effects. Most people are familiar with the euphoric effects of drugs. But to the addicted brain, drugs do not bring euphoria; they merely keep it from crashing into despair. Withdrawal includes the phenomenon of intense craving as well as (with many drugs) physical side effects such as hallucinations, nausea, tremors and aching bones. Heroin and opiate addicts refer to withdrawal as "getting sick." For some alcoholics, withdrawal can be deadly.

- North Coast Journal

- Drug-Related Deaths

An addicted brain, they say, is a brain permanently changed. Some compare addiction to an allergy. Any return to mind-altering substances, even the smallest sip or toke, can trigger an allergic reaction: the craving for more, and a return to the insanity of active addiction. Once an addict, always an addict.

Counselors like Ward often struggle to convince their clients that they can never return to using. Often there are physical deterrents to use: a cirrhotic liver that will shut down if an alcoholic begins drinking again, collapsed veins that won't accept needles. Despite this, addicts often succumb to cravings and begin drinking or using again. Denial of the chronic, fatal nature of addiction can be very strong.

"If people are looking at it from the outside it looks like a straight downward spiral," Ward says, "But when you're in addiction it doesn't feel that way."

Under the medical model, addicts are essentially playing mad scientist with their brains – using various chemicals to return to equilibrium, to a place that doesn't hurt. Many will continue that pursuit through the consequences of lost health, lost jobs, lost children; into institutions, insanity and death. But some say the disease model of addiction doesn't fully resolve the conundrum of what makes an addict in the first place.

The Trauma Model

Ward began drinking and using at the of age 11. The son of an alcoholic single mother, he says that as he entered adolescence in the turbulent 1970s, the stage had been set, psychologically, for him to become an addict.

"Drugs weren't the problem, not being able to deal with life was the problem," he says. His words echo the logic behind researchers who promote the trauma model of addiction theory. The trauma model endeavors to answer the omnipresent question of addiction's cause. How can one fraternity brother drink his weight through college and eventually evolve into a sensible middle-aged tippler, while another may end up dying of cirrhosis as a chronic alcoholic? The answer, some say, lies in early childhood brain development.

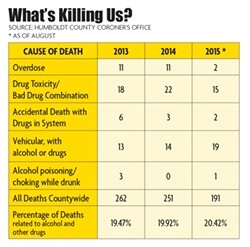

- North Coast Journal

- What's Killing Us?

The crucial synaptic pathways that govern such traits as empathy and impulse control develop in early and middle childhood. Sustained stress brought on by abuse, neglect and traumatic events can interrupt and damage this neurological process, leaving people vulnerable to using alcohol and other drugs to compensate for low levels of dopamine and other important mood-regulating chemicals. People diagnosed with mood or anxiety disorders are about twice as likely as the general population to also suffer from a substance use disorder, according to the National Institute of Health. The NIH does not assert a correlation between drug use and mental illness, but trauma theorists do, saying that addicts are often using drugs unwittingly as psychiatric medication. Repeated use of any drug will create physical and psychological dependencies.

One prominent trauma theorist, Gabor Mate, visited Humboldt State University for a three-day trauma symposium in 2014. In his book, In the Realm of the Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction, Mate writes, "The absence of [consistent parental contact] makes the child more vulnerable to 'needing' drugs of abuse later to supplement what her own brain is lacking." Both Goldsby and Humboldt County Chief Probation Officer William Damiano attended the symposium, adding their perspectives on three decades of changing treatment methods.

"Trauma-informed care has everything to do with what we're trying to accomplish in corrections," says Damiano. "We have to have an idea of its impact on those we work with. We know from neuroscience that those who have had a traumatic upbringing and traumatic events...physical, mental, assault, neglect, poverty and malnutrition, parents being removed from home, those things have significant impacts. We have to be very aware of what kinds of things shaped people coming into our system. That's what the corrections business is all about."

Damiano says there is a lot of evidence to support the idea that Humboldt County residents are exposed to an exceptional amount of trauma. According to the California Department of Public Health, one in four Humboldt children live in poverty. The California Child Welfare Indicators Project at the University of California at Berkeley reports that, in 2014, close to 9 percent of children in Humboldt were involved the child welfare system, as opposed to the state average of a little over 5 percent. Almost 6 percent of school-age children in Humboldt County are homeless. We also far outrank the state average in maltreatment allegations involving infants and toddlers, averaging 135 cases per 1,000 infants between 2007 and 2014. The state average is 65.

- Photo by Linda Stansberry

- Humboldt Bay Recovery Center Executive Director Arlette Large

"Most of the women I work with have a history of trauma in one way or another," says Arlette Large, executive director of Humboldt Recovery Center. The National Institute on Drug Abuse conducted a twin study in 2002 that concluded that women who were sexually abused as children are at greater risk for drug abuse as adults. (There are also high rates of substance abuse disorders among returning military veterans.)

"Most of our patients have some type of trauma," she adds. "It doesn't mean that everyone has one. Some people come from a great background, a great family. But then they started hanging out with people using Vicodin and Oxycontin, and the next thing they know they're strung out."

The Genetic Model/The Rat in a Cage Model

A classic animal study, begun in the 1950s, may offer the best perspective into the multi-faceted nature of addiction's causes. In it, scientists bred two strains of mice, one with a hereditary love of alcohol and the other with a hereditary hatred of alcohol. It exposed the mice with a genetic dislike of alcohol to three different risk factors: over-exposure to alcohol, stress and food deprivation. In each case, the mice became alcoholic, exhibiting brain cell changes and neurotransmitter imbalances indicative of addiction. The alcohol-loving mice needed no such stressors. Mere exposure to alcohol turned them into alcoholics.

For several decades, science has suggested a genetic component to addiction, even isolating the specific genes that make people vulnerable to becoming addicted to one drug over another. The A1 allele of the dopamine receptor gene DRD2, for example, is more common in people addicted to alcohol or cocaine. But, as with other troubling genetic inheritances such as cancer, environment and behavior can influence gene expression. Trauma theory, disease theory and genetic theory are not mutually exclusive. Nor do they exempt addicts from making healthier choices. Just as someone with a family history of skin cancer might choose to wear sunscreen, a teenager with a family history of addiction might choose not to imbibe.

But how likely is that? Goldsby, Damiano and Stewart all credit the easy accessibility of drugs in Humboldt County as a part of the issue. Damiano says that the black market marijuana industry compounds the problem, both by creating an isolating culture of secrecy and normalizing its use.

"Our biggest challenge as a community and a county is how to engage in a new way of thinking," he says.

In the 1970s, a college professor, Bruce Alexander, did a variation on the mice studies that introduced an entirely new variable. His argument? Of course the mice were turning into alcoholics, they were in cages. Dr. Alexander created a "park" instead, with more stimuli and activities. Using rats, he experimented with the effects of isolation and environment on propensity to addiction. His studies suggested that environment is an important factor in preventing addiction.

So, where do we stand? Are Humboldt residents rats in barren cages, with nothing to ease our existence but narcotics? Well, we are exceptionally isolated, with only about 37 people per square mile. Along with our troubling statistics on child welfare, we also have a higher average of domestic violence reports than the state. And 20 percent of families in Humboldt County live below the poverty level.

Of course, we may also have what addiction professionals call "resiliency factors." Our fierce sense of rural independence and how-to. A slightly higher rate of high school graduates than the state average. Clean air and extraordinary natural beauty. A culture that tends to value philanthropy and social activism.

The work of counselors such as Ward and Large seem to speak to this last factor. Both acknowledge that recidivism is common among their clients (an estimated 40 to 60 percent of recovering addicts relapse) and that there doesn't seem to be an end in sight. Ward lives for the moments when the denial breaks and a client is truly ready to accept help.

"Once the fear of going back is greater than the fear of going forward, you'll go forward," he says.

Humboldt County may be at a similar crossroads. Drug and alcohol related deaths made up an average of 20 percent of our total fatalities for the last three years, raising the scope of the issue from moral quandary to public health crisis. What would it look like to go forward? In Part 2 of this series, we will meet some of the men and women fighting for the lives of addicts on the Redwood Coast, and the barriers to treatment.

Comments (8)

Showing 1-8 of 8