It has become the embittered whine of the Obama era -- the half-sarcastic, half-genuine plea of jealous sad sacks nationwide: "Where's my bailout?" Those who've been suddenly knocked a few rungs down the capitalism ladder are looking around dumbfounded, wondering what the hell happened. But here on the Redwood Coast, there have long been struggling folks tucked in the verdant crannies along our rivers and hillsides, living in poverty on our reservations, even hiding in plain sight within our towns -- folks whose troubles far predate the Wall Street collapse, the burst housing bubble and the unholy disaster of our state budget.

The economic crisis that has so many bankers and brokers in a tizzy hardly even registered with these down-and-out rural families here on the far north coast of our massive, unwieldy state. In a 2006 survey, nearly 20 percent of Humboldt County residents said they were unable to get needed health care during the previous 12 months. For those living in poverty that number was double. Twenty-three percent of low-income respondents couldn't get necessary health care for their children. And almost one in 10 county residents experienced hunger because they couldn't afford enough food. These are people who have needed a helping hand for years -- generations, even -- but they've been largely overlooked by the powers that be, not always because of callousness or indifference. They're just hard to see from so far away.

Until recently, policymakers have relied on patchwork information gathered by and housed in institutions hundreds of miles away from these citizens. Similarly, the assets of rural communities -- our willingness to cooperate, our social bonds -- are also overlooked, blurred into generalizations by groups analyzing the entirety of California, the country's most populous state, which, if you haven't heard, is on the verge of bankruptcy. State lawmakers, trying to close the $24.3 billion budget deficit, are considering unraveling huge sections of the social safety net, including eliminating Healthy Families, which provides health insurance for 930,000 low-income children, as well as CalWORKS, the state's lauded welfare-to-work program.

Dr. Sheila Steinberg, an associate professor of Sociology at Humboldt State University, says there's something deceptively simple that may be able to help poor, rural people in the region and throughout the state: data. As in, information -- specific information on the issues affecting rural citizens, gathered methodically, housed locally and made available to both the public and the policymakers whose decisions affect them. "The average person doesn't realize how important [data] is," says Steinberg. "They think it's just an academic thing. But really, data translates into money, because if you can show the need, if you can tell the story with the data -- and document it -- then you can go seek grants, and then you can help people."

When she's not teaching courses like "The Changing Family" and "Environmental Inequality and Globalization," Steinberg serves as director of community research for the California Center for Rural Policy (CCRP), a research center housed on HSU's campus whose goal is to help rural citizens through research conducted for and by those very citizens. For example, those statistics mentioned above concerning health care and hunger in Humboldt County? Those came from the CCRP. Since forming in the fall of 2005 the center has reported on such rural concerns as Internet connectivity, pesticide use and health care among the North Coast's growing Latino community.

"Everybody has for a long time complained about the data that's collected on our region," says CCRP Executive Director and former Arcata Mayor Connie Stewart. "When we're graded or rated, that data doesn't really tell the story of what it is to live in rural California." Often, she explains, vast rural areas are slapped with letter grades or numeric scores based on relatively small data samples collected from hundreds of miles away. For example, the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), a random-dial census conducted every other year by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, lumps together the counties of Del Norte, Siskiyou, Lassen, Trinity, Modoc, Plumas and Sierra. (Humboldt stands alone, but that's hardly nuanced enough for the CCRP.) These broad surveys are regularly used to inform significant policy decisions made by legislators, local health departments, state agencies, community organizations and more. Not only does this method paint complex rural regions with too broad a brush, Stewart says, it inherently misrepresents the populace.

"We found out that about 14 percent of people don't have a phone in the region of Humboldt, Del Norte, Trinity and Mendocino [counties], which is about the size of Connecticut and New Jersey put together," Stewart says. "And of course the majority of those who don't have a phone are poor. So you're already skewing your data by electing to do a phone survey rather than a mail survey." (CCRP directors explained the problem with phone surveys to CHIS personnel, who decided to change their methods next time around, Stewart says.)

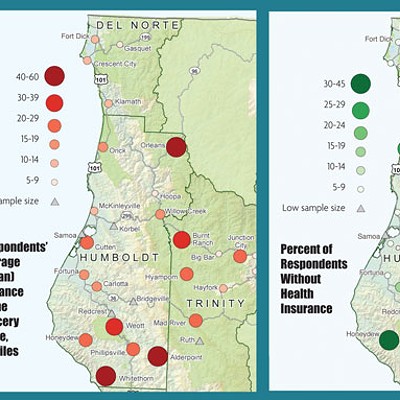

The CCRP doesn't just gather the information; they package it, along with existing data, into snazzy, colorful maps using GIS (Geographic Information Systems) technology. If you haven't heard of GIS, you've almost certainly seen its results. Used in nifty technology like Google Earth, GIS offers a way to capture, manage and present data linked to location. Those red-and-blue electoral maps shown on cable news during the presidential election are one example of GIS mapping. While GIS has long been used in the natural sciences, the CCRP is one of just a few organizations combining the technology with the social sciences. Steinberg calls the resulting field "socio-spatial analysis" -- the examination of people and their connection to space and place. The GIS maps created for the CCRP show such information as where poverty is most highly concentrated or even how local media portray Latinos.

Coincidentally (sort of), the GIS expert at HSU is Dr. Sheila Steinberg's husband, Dr. Steven Steinberg, a fellow associate professor and director of the university's Institute for Spatial Analysis. (More on that "sort of" in a minute.) Citing the old adage that a picture is worth a thousand words, Steven Steinberg says GIS maps help make information accessible to the general public and, perhaps more importantly, to politicians. "Given what a typical politician has time to absorb, maps offer a way to very concisely communicate a lot of information quickly," he says.

His wife agrees. "If you're a rural community and you're gonna go argue your case to get resources, you can't just go say, 'We need stuff.' You have to be able to show and document: 'This is what we need; this is why we need it; this is what the numbers say.' And that's the role that I see our organization providing."

Sheila Steinberg's office sits on the top floor of HSU's Behavioral and Social Sciences building. With the semester over, this massive, eco-groovy new structure is practically empty, as is the rest of the campus (most of which can be seen out Steinberg's window). The balconies on the opposite side of the building offer a panoramic view of Arcata, framed by horizontal redwood branches, with silvery Humboldt Bay and Eureka beyond. Looking younger than her 42 years, with rosy cheeks and a chipper voice, Steinberg gets animated when discussing her work, emphasizing points with sweeping hand gestures. Her declarative sentences are often punctuated with a lively, rhetorical "right?"

Given her passion for the subject, it would be tempting to assume Steinberg comes from a rural background. "No-ho-ho," she says with a self-conscious chuckle. "Uh, I'm from L.A." Among other places. Steinberg's Obama-like upbringing (her Hindu father's from India; her mom's a Kentucky Baptist) took her from the urbs and suburbs of Delaware, Connecticut and New York to the concrete jungle of La La Land. Her love for the pastoral, born, she says, on childhood visits to her grandpa's Kentucky farm, eventually led her to UC Berkeley, where she earned her Masters in Forestry while focusing on Natural Resource Sociology. Encouraged by one of her professors, she then went uber-rustic, serving three years with the Peace Corps in rural Guatemala where she worked side-by-side with the community on watershed management and tree-planting. "It was a real interesting experience," she says dryly.

Afterwards, she went on to earn a PhD in Rural Sociology from Penn State. "That's where I got exposed to GIS, and I started bringing that into the study of people in the context of their place," Steinberg says. When she arrived at HSU in 2000, her department chair told her to go find the GIS expert on campus. "I was really annoyed with that request because I was new and I didn't want to deal with it. So I found out who it was," she says, beaming, "and it was this guy, Steve Steinberg."

Needless to say, they hit it off. With his background in Natural Resources and minor in Sociology, Dr. Steven Steinberg, now 39, had plenty in common with Sheila. After some good conversations about GIS research and the like, Steven started showing up in Sheila's classroom, watching the tail ends of her lectures and helping with balky technology like overhead projectors. "We started off as friends, then started writing grants and sharing research ideas together. And then it evolved," she says. They were married in 2002 and had a son, Joshua, the following year. "We call it 'GIS love.'" Her laugh fills the office. "So academic, right?"

The CCRP, appropriately enough, came from the community, born out of a diverse local effort to cooperate on a common goal -- sort of a local Fellowship of the Ring. Beginning in 2003, ranchers, timber workers, law enforcement, health care personnel and more -- representing Humboldt, Del Norte, Trinity and Mendocino counties -- met regularly to discuss rural issues in the hopes of solving nagging problems in the spheres of health care, education and technology. The main organizers included Peter Pennekamp and Kathleen Moxon of the Humboldt Area Foundation, Humboldt Open Door Community Health Centers Executive Director Hermann Spetzler, Casey Crabill (then-president of College of the Redwoods) and HSU President Rollin Richmond.

In an e-mail to the Journal last week, Richmond explained their motives. "We believed, and I think our ideas have been supported, that rural areas like our region often do not receive the attention they deserve when data are gathered about many issues ... particularly health care, poverty levels, education and access to important services like the Internet and, for some locations, even telephone." Two groups were established from these efforts: Redwood Coast Rural Action (a network of local community leaders now led by Moxon) and the CCRP, which is primarily funded through grants from the California Endowment and the California Wellness Foundation and operates under the umbrella of President Richmond's office.

Steinberg says the CCRP wouldn't have happened without Richmond's vision and commitment. "He stepped up to the plate and said, 'We'll house it at HSU; we'll make some space; we'll donate some resources for it; and my office will be committed to supporting it.' And I'll tell you," Steinberg says, "if he hadn't done that, it wouldn't have happened."

In the fall of 2006, the CCRP began gathering information with a four-page survey sent to randomly selected post office boxes throughout the Redwood Coast region (Humboldt, Del Norte, Trinity and Mendocino counties). The Rural Health Information Study (RHIS), as it was called, was designed to explore how poverty and place impact health. "This is the largest study of this type that has ever been conducted in this rural region of California," wrote study author and CCRP Director of Health Research Dr. Jessica Van Arsdale. The results were illuminating. Thirty-five percent of low-income respondents between the ages of 18 and 64 were without health insurance (compared to 10.8 percent above the low-income mark). People living in poverty (less than $20,444 per year for a family of four) were 4.6 times more likely to report poor or fair health compared to those making three times that amount.

"There's a lot more hunger out there in our community than the national or state average, which was pretty shocking," says Stewart. The Redwood Coast Region's poverty rate in 2000 was 18.3 percent, compared to 14.2 percent for California and 12.4 percent nationwide. While that particular information was available through the U.S. Census, the CCRP mapped the data using GIS and added new levels of information with their survey results, allowing them to identify, for example, where poverty was most concentrated. (Hoopa had the highest rate, followed by the remote areas of Humboldt, Trinity and Mendocino counties and, surprising many, Arcata and Eureka.)

"When we first created those [maps] and put them up three years ago, people kind of went crazy for them," says Steinberg. Stewart remembers taking the poverty maps to an Arcata City Council meeting during the fluoride debate. "I'll never forget it," she says. "One of the council members, one of the anti-fluoride advocates, got up and said, 'There are no poor kids in Arcata.' I was like, 'Maybe in your neighborhood.'"

That's the value of the CCRP's maps: By packaging lots of information into simple, visually arresting graphics they have the power to destroy assumptions and convince decision-makers to rethink their priorities. The CCRP uses a technique known as community-based participatory research, which essentially forms an equal partnership between the community and the experts (or "people with letters behind their names," as Steinberg calls them). With help from various HSU professors, as well as student research assistants and members of the communities they study, the CCRP has completed numerous reports in recent years, managing to effectively change policies in a number of cases.

The Rural Latino Project, completed in 2008, investigated the health issues facing the fastest-growing minority group in the region. The goal was to explore both the challenges and strengths of the local Latino community in order to provide some baseline information and a place-based understanding for those hoping to serve them. Two thirds of interviewees who work closely with local Latinos said the group's health needs are not being met. "We need to be able to effectively serve the Latino population because they're contributing to [the region's] growing birthrate," said Wendy Rowan, executive director of First Five! Humboldt. According to Rowan, the CCRP's Rural Latino Project provided key information about Latino-focused programs like St. Joseph Hospital's parenting and prenatal program Paso a Paso (Step by Step). "The report reaffirmed the value of the program and helped us think more about how we can enhance what we do," she said. "Until we have reports like this, we're kind of guessing."

The McLean Foundation, a nonprofit formed 10 years ago following the death of Eel River Sawmills owner Mel McLean, commissioned a report on the needs of people in the Eel River Valley. "People saw a need for a multi-generation community center," said McLean Foundation Executive Director Leigh Oetker, "a place for not only teens but seniors." Plans for the center remain in motion, though Oetker said the economic meltdown has slowed things down a bit. Still, she said, the work of the CCRP was invaluable. "The expertise they have there is pretty fantastic," she said. "I think they're at the beginning of seeing the work they're doing have a real impact."

That work has not been limited to the North Coast. Last year, the CCRP published a report on pesticide use in Monterey and Tulare counties. Titled "People, Place and Health: A Socio-spatial Perspective of Agricultural Workers and Their Environment," the 94-page report was accompanied by a 143-page atlas filled with bright GIS maps and quotes from community leaders and agricultural workers. Following the report's completion, Radio Bilingüe reporter Alma Martinez helped present the information to farmworkers in three Tulare County communities. The workers were told about the short-term and long-term health effects of pesticides and about laws governing their use. Most of these workers were at least somewhat familiar with the material, but when they saw GIS maps showing pesticide drifts near elementary schools, their attitude changed.

"When they saw the maps, that is what prompted them into action," said Martinez last week. Another advantage to the CCRP maps: They can cross language and literacy barriers. In the weeks that followed, workers formed comités -- community action committees -- and set out to convince Tulare County authorities to enact and enforce quarter-mile buffer zones around schools and playgrounds. It worked: Aerial pesticide spraying has been banned in those areas.

As Steinberg told Humboldt Now, the university magazine, the CCRP's research gave validity to citizens' complaints. "We interviewed community members who had been dismissed in the past as uneducated farm workers when they reported autism, unusually high rates of twin births and people sickened with asthma or migraines," she said. "We provided them with visual maps and technical assistance to trace pesticide applications. We gave voice to their concerns through our research."

The comités continue to work. Next school year the groups hope to establish a flag system to warn parents when sprays are scheduled, and they're trying to convince school officials to utilize an existing emergency call system for the same purpose. The CCRP's report, compiled with the help of HSU undergrad and grad students, contains numerous recommendations directed at farm owners and legislators.

Sitting in her office on the top floor of the tallest building in Arcata, Steinberg says the CCRP has just begun to realize its potential. She envisions the center as a place where rural Californians can come not just for problem solving and analysis but for diagnosis. "You take a car in to a mechanic, right?" she says. "As the driver of the car it's not your job to know what you need done. That's the mechanic's job. So we're kind of like the mechanics of rural California."

In addition to the grant-funded studies, Steinberg says the center does contract work, like a recent project in which they helped a Native American tribe (she didn't want to say which one) prove to the state government that they'd been under-counted in the 2000 U.S. Census and were therefore entitled to more state funding. Steinberg and the other CCRP directors are hoping more groups will seek them out for this kind of work. They've also begun sponsoring workshops, like a UCLA-organized community training session called "Data and Democracy." (Part two of that workshop takes place this Thursday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. in Nelson Hall East, room 102.)

"CCRP is building confidence and capacity," Stewart says. "The first couple years we were just doing the data collection for the studies." The economic downturn likely means that things may get worse before they get better. But Stewart says that makes the CCRP's job all the more important. "Resources will be even tighter, and we have to be even smarter with how we use them."

Of course, vulnerability isn't the true hallmark of rural folks. We pride ourselves on being hardworking. Resourceful. Self-reliant. We're not gonna sit around waiting for a government bailout, dammit. Part of living behind the Redwood Curtain means learning how to take care of our own.

"I think when you live here you know that help isn't always going to come from the outside," says Steinberg. "We have to be able to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps and help each other. And that ties in with the whole formation of [the] CCRP." Steinberg may have grown up in cities and suburbs, but she's got the defiant Humboldt attitude down pat. "Let's not rely on the big schools to come in and study us as a rural community under the microscope," she says. "Let us study ourselves. Let us decide how we want to be portrayed. Let us be the holder of the data. And then we have it to share with others in the community, and then we can empower ourselves -- because knowledge is power, right?"

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1