|

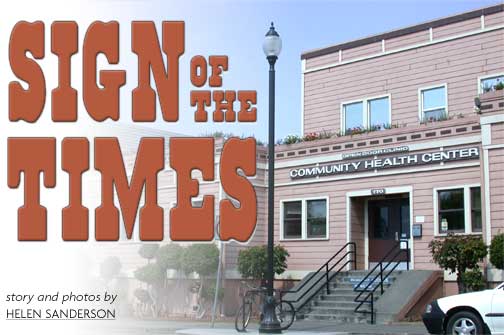

COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | FROM THE PUBLISHER | OFF THE PAVEMENT September 14, 2006

THE OPEN DOOR CLINIC'S ADMINISTRATIVE QUARTERS PROVIDE GREAT VIEWS OF THE ARCATA PLAZA. On a recent Thursday afternoon, the square was bathed in sunshine for what felt like the first time in weeks and the lawn was beginning to bustle. But in his corner office that overlooked it all, Hermann Spetzler seemed suddenly tired. For almost two hours until that point, the 58-year-old,

Birkenstock-shod Spetzler talked with gusto and clarity on Left: Humboldt Open Door Clinic, in the 1970s. Photo courtesy Humboldt Open Door Clinic. "It was really undignified," he said of Open Door's early office, which was modeled after the Haight-Ashbury street clinic movement. Despite this, it's clear that Spetzler regards those early years as something of a magical time in the clinic's history, when a young idealistic counterculture united with the shared belief that all people had the right to healthcare, not just those who could afford it.

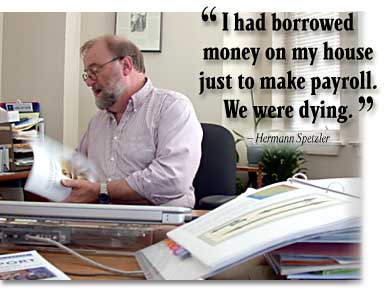

Right: Hermann Spetzler, executive director of Humboldt Open Door Clinics. It was at this juncture in the conversation that Spetzler abruptly lost his steam and sank back in his chair. "This month has been hard for me," he said. "Friends my age have died." He was referring to longtime NEC Director Tim McKay, 59, and Open Door dermatologist, Dr. Gene Blum, 57. "I feel like it's 30 years too soon."

By all accounts, the original Open Door was funky. Located in what is now the Tin Can Mailman bookstore, the clinic had no real exam rooms, only sheets as dividers. Lighting consisted of naked bulbs dangling from wires. Dogs were welcome and occasionally received treatment. But mainly, those early years were spent as a referral center, where people could get information about anything from pregnancy testing to food stamps. It kept list of a "crash pads," where people just coming to town could sleep for a while. By 1972, the clinic had 27 phone counselors, volunteering every day. A year later, physicians volunteered medical services two days a week. A number of those early volunteers are still working in Humboldt County today. Among them is Martin Love, CEO of the Humboldt-Del Norte Independent Practice Association and former CEO of Eureka's General Hospital. Love, then only in his mid-20s, created a makeshift laboratory to do blood work for the clinic. Last week he said that his role in the clinic was very small and figured few would even remember he ever volunteered there. He was a student at Humboldt State University and worked at General Hospital to pay tuition. "We were working with equipment that I borrowed from around town, from the hospital, very primitive," he said. "We were all hippies and having a good a time.... Don't write that down." Arcata attorney Ira Blatt, 60, also got his start at Open Door. He became the clinic's administrator in 1972, providing legal aid and workshops on divorce and welfare. His salary was $400 a month. "You had professionals who had very full professional lives and families and they were willing to work an extra three hours once a week," he recalled. "It was the nature of the times and it was also the aspect that most people were very committed to the community and saw that there were other people willing to help, and they could train very young people, very energetic people." One of those young, energetic people was Susan Riesel, now 60. Riesel came to Arcata from San Francisco in 1974 and soon started volunteering at the clinic. She trained under Dr. Gena Pennington through the women's health collective. When Pennington and the collective broke with Open Door to start the North Country Clinic, Riesel stayed with Open Door instead, where she was offered permanent employment.

Today North Country is once again part of Open Door Community Health Centers, the broad umbrella group that grew out of the original Open Door Clinic. Left and below: Open Door Clinic during construction in the 1980s. Photos courtesy of Humboldt Open Door Clinic. Riesel's husband, David Horwitz, is also an Open Door employee who got his start there in the 1970s. "I was a young radical and wanted to work for social change and so I looked around the community to see who was doing what and came to Open Door," he said. "There weren't a lot of health services being offered and not a lot of paid staff but I said, `What can I help with?' and ended up working as a welfare rights counselor." Horwitz later became the program coordinator for the early mobile medical unit that traveled regularly to Redway and was, for a time, the acting administrator before Hermann Spetzler was hired as executive director in 1977. "By the time Hermann came, we needed a real administrator," Riesel said. "He had real experience. It was amazing that someone at that level would want to work for this storefront building." Before arriving in Humboldt, Spetzler ran a multi-site drug and alcohol program in Tahoe. He and his wife, Cheyenne Spetzler, who is now the operations manager for Open Door, came to Humboldt so she could attend HSU. During Spetzler's first year at the clinic, he earned $5 an hour. "Thirty-five people interviewed me," Spetzler said, remembering that the clinic was operated by consensus back then. "I could see that there was tremendous potential and everyone there really cared and worked as a team."

And as the clinic gradually earned a greater sense of legitimacy in the community, more patients came. By 1978 they'd outgrown the clinic. "We began to have a real medical practice," Riesel said, "and that meant real income. So one day Hermann says, `Let's buy the building next door.' It was a funeral parlor! We thought he was nuts, it was beyond our comprehension. "He always had a can-do chutzpah. He can take something that seems like it can't be done and make it be so." In 1979 Open Door began a lengthy process of fundraising to buy Paul's Chapel. After three years of constant battling with the United States Department of Agriculture for a large rural healthcare grant, Spetzler went to Washington, D.C. to beg. "I met with Reagan's assistant for health care and explained that I had borrowed money on my house just to make payroll. We were dying," Spetzler said. "Three or four days after I made it to the White House the check came and we were able to pay our bills." (Spetzler's trip to the capital was an important lesson on how to affect change at home, using state and national resources. He frequently travels to give talks on rural healthcare issues and has become a well-known figure in California's healthcare community.) Also during Open Door's adolescence, Spetzler lobbied to hire a young, bright couple, Drs. Ann Lindsay and Alan Glaseroff. Lindsay, 54, recalled attending a potluck at Spetzler's geodesic dome in Kneeland during a visit to Humboldt. She and Glaseroff soon realized it was a job interview. They agreed to relocate from San Francisco to Arcata in 1983, each working half time at the clinic to fill one full-time physician's position and sharing the duties of raising their toddler daughter, Rebecca. Between them they made $35,000. A year later they started their own practice, which they operate to this day. "At that point [1983], the docs were really trying to lay down some continuing care, so it was becoming less of a drop-in to more of a place you take care of people time after time," Lindsay recalled. "We had a home birth program, an excellent obstetrics program and lay midwives. It was a good team approach. "The focus we had then was also establishing ourselves as part of the medical community and not just the clinic over there." And while the Open Door was beginning to wash itself clean of its grungy beginnings, the image was hard to erase, especially with the old-school docs. Dr. Glaseroff, 54, recounted a running joke from the 1970s and '80s about Open Door physicians. It goes like this: A putrid-smelling homeless person, covered in grime and body lice arrives at Mad River Community Hospital's emergency room. The doctor enters the exam room and immediately evacuates, gasping for air. Another ER doc meets the same fate. They call an Open Door doctor. He undauntedly enters the exam room. A minute later the homeless person bursts through the door, gagging. "Back then there was a lot of discrimination," he said. "Now it is one of the best places in town." And definitely one of the largest. While many private practices have closed in recent years, Open Door has become the biggest provider of primary care north of the Bay Area, seeing 36,000 patients a year.

Construction on the new clinic wrapped in 1984 and, as Riesel recalled, a shaman came to shoo the bad spirits away before they opened for business. Their patient load grew larger, and by 1986 they'd outgrown their new clinic. In 1990 a center in Crescent City opened and a year later a Eureka office. From there Open Doors came to Smith River, Orick and McKinleyville, along with a dental office in Eureka. "In some of these places we are the sole care provider," Spetzler said. Today one in four Humboldt County residents and one in three from Del Norte use Open Door clinics. It's no longer limited to healthcare for the poor and uninsured. And while the health centers have seen major growth in the past 35 years, times are tough for everyone in the health field right now. In addition to reimbursement issues plaguing hospitals and medical practices everywhere, rural areas have it extra tough in recruiting doctors. For one, Humboldt County doesn't have the culture and nightlife that a metro area can offer a young doctor. Secondly, the North Coast can't pay as well. Many doctors fresh out of medical school start their career more than $100,000 in debt. "There is so much pressure they have to pay their debts off that there is no way that they can make the kinds of choices that the physicians or the lawyers of my generation could make," said attorney Ira Blatt. Dr. Glaseroff is a case in point. "It cost me $4,000 a year for medical school," he said. "Now it costs $55,000 a year. I came out with no debt, so I could do whatever I wanted. Now they make choices to pay off their loan." Glaseroff and Lindsay's daughter is currently applying to medical school at the University of California at San Francisco, the same school where her parents met. According to Lindsay, a number of doctors in the area have recruited their own children to work beside them after medical school. She calls it "growing your own." Ira Blatt noted that his generation felt freer than those before him. "People in my parent's generation were raised in the depression," Blatt said. "They had no choice. You were lucky if you had a job. No one said, `What would you like to do?' People in my generation had a choice. They had a sense of, `I want to make a difference with the work I do.'" But it is a generation that is getting old. The average age of a doctor in Humboldt County is 54 years old, according to Lindsay. The primary care doctors who came of age in the 1970s are now nearing retirement age. And with fewer general physicians in the med school pipeline they're beginning to wonder who will replace them. Over the years larger numbers of students have entered training for medical specialties, which can reap higher salaries. "People are leaving right and left and not being replaced," Lindsay said. "I don't think I could find somebody to take over my practice. I'm still young enough, but I worry sometimes. I want my patients to have a place to go when I can't do this anymore."

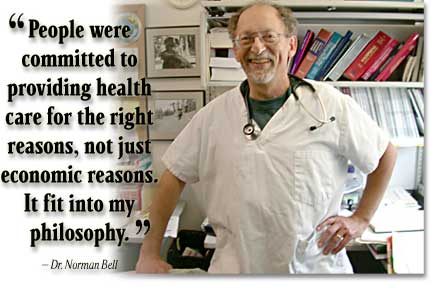

Right: Dr. Norman Bell. Another boost to Open Door's recruitment efforts is that the federal government considers the North Coast a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA). The designation benefits Open Door because it makes it eligible for federal National Health Service Corps scholar grants to bring doctors out of medical school to underserved areas like Humboldt County. "It gives community health centers leverage in competing with highly desirable, urban areas," said Donna Eddings, performance improvement officer for Open Door. "When you have a high enough HPSA rating then you qualify as an eligible site for about 200 scholars coming out of residency and finishing their education." In the past few months, 10 medical professionals, including doctors, dentists and physicians' assistants, have been recruited to Open Door clinics in Del Norte and Humboldt. The program pays off the students' loans in exchange for two to three years of work in a rural area. "I know a lot [of health care workers] come here for loan repayment, and once they get two or three years through they look for something different," said Dr. Elena Furrow, 32, a family practitioner who has been with Eureka's Open Door clinic for two years. "I would say, generally speaking, if you are young, Humboldt County is not the place to be. Some have left for that reason. If you're already settled down and want a quiet place to live, it's good. The people who work here are very nice and supportive, but it is not good pay and that's hard to justify when you don't love it." Unless the doctors can be convinced to stay, loan repayment might be a short-term solution. "Believe me, we will do everything we can to keep them here," said Eddings.

Dr. Norman Bell, 63, was one of Open Door's first paid physicians (along with Dr. Gena Pennington). After finishing a fellowship in community pediatrics at Harvard's Beth Israel Hospital, he traveled the country and made his way to the Northwest in 1976. Last week, Bell took an afternoon coffee break at Sacred Grounds, opting to pull a chair outside and sit in the sun, brandishing sunglasses that fit over his eyeglasses. The barista delivered him his drink. "See," he said. "They're nice to you when you're old." What was his impression of Open Door in the '70s? He thought a moment and pointed toward the small, scraggly garden outside of the cafe. "It was like if you're a gardener looking at some soil and saying, `Wow this could be a great garden someday.'" But more than its potential, Bell said what he most liked was the clinic's mission -- to provide healthcare for people who otherwise had no access to a doctor. "People were committed to providing health care for the right reasons, not just economic reasons," he said, sipping an espresso. "It fit into my philosophy."

Left: Frank Anderson, in a teleconference. And as for that scraggly clinic where he began, Bell recently took a step further away from that low-tech past. Two weeks ago, he saw his first set of patients using the "telehealth" real-time video conferencing system. He virtually visited five children in Crescent City with mental health issues. Each visit lasted a half-hour, and Bell will continue to meet with them once a month. Telehealth is another tool Spetzler believes will attract new doctors to the North Coast. Since the Telehealth and Visiting Specialist Center opened in Eureka last April, the majority of doctor visits have been transmitted to Humboldt Country rather than to another area. Psychiatry, dermatology and endocrinology are three of the most used services, since there is a severe shortage of those providers locally. "For years [telehealth] has been this exotic thing," said Frank Anderson, director of Eureka's telemedicine clinic. "But we're making it routine, like using a computer." The way it works with dermatology for instance, is that pictures are taken of a person's skin ailment and sent, via something similar to e-mail, to an out-of-area doctor. The process is called "store and forward" and MediCal recently began reimbursing Open Door for the work. For many patients, this method saves time and money spent traveling to the Bay Area for treatment. But instead of ushering care out, Spetzler is focused upon bringing specialists here -- like neurologists, for instance. This way Humboldt can become a "telehealth hub" rather than only feeding off metro areas. He sees this movement as an important economic development issue for the entire county, with its resource-based industries dwindling. "What we know is that every doctor that we attract to this community is approximately a $1 million $2.5 million enterprise," he said, "because it isn't just the doctor, it's the receptionist, the nurse, the back office person. Those are good middle class jobs." Further into the future, many healthcare watchers on the North Coast think private primary care practices will join forces rather than continuing to compete, creating two or three large, multi-specialty practices from the existing 26 offices.

"I was concerned that it was too much Tim," Spetzler said, looking somewhat overburdened. He told McKay about his own approach, "to grow the clinic to a point where it didn't need me anymore." Left: Telehealth center in Eureka. A moment later, a second wind seemed to sweep away his gloom and he sat up taller. He talked more optimistically, saying that although McKay didn't lay the NEC's plans for transition as well as he should have -- he was well-known for keeping his plans in his head rather than on paper -- the fruits of his labor in the environmental realm will carry on simply because the spirit of the work resonates deeply with activists here. While Open Door is an entirely different animal than the NEC, the ideals and dedication that made it flourish are similar. For doctors coming into practice today, it's just not possible to simply volunteer, or work only part-time for little money. But the physicians of Spetzler's generation don't expect that of them anyway. "When new, young doctors are still choosing Open Door, it will mean it has reached a level of life beyond its leadership," Spetzler said. "Most good things here are like that." COVER STORY | IN THE NEWS | FROM THE PUBLISHER | OFF THE PAVEMENT Comments? Write a letter! © Copyright 2006, North Coast Journal, Inc. |

various

healthcare topics, from the challenges of recruiting young doctors,

to the latest in "telehealth" technology that connects

local patients with out-of-area specialists via video conferencing.

He spoke angrily about how the structure of primary healthcare

has been turned on its head. He likened it to an inverted pyramid,

with physicians and patients being crushed beneath massive layers

of bureaucracy. He went on to chronicle the clinic's 35-year

transformation from a hippie-run, ramshackle Arcata storefront

on 10th and H streets to what now encompasses nine clinics and

almost 300 employees, from Smith River to Eureka.

various

healthcare topics, from the challenges of recruiting young doctors,

to the latest in "telehealth" technology that connects

local patients with out-of-area specialists via video conferencing.

He spoke angrily about how the structure of primary healthcare

has been turned on its head. He likened it to an inverted pyramid,

with physicians and patients being crushed beneath massive layers

of bureaucracy. He went on to chronicle the clinic's 35-year

transformation from a hippie-run, ramshackle Arcata storefront

on 10th and H streets to what now encompasses nine clinics and

almost 300 employees, from Smith River to Eureka. It

wasn't just the clinic that was making strides at the time. The

first wave of liberal activists were infiltrating Arcata and

rattling cages over everything from the Vietnam War to bike paths

through the city. America was in the midst of an energy crisis,

and environmental issues in particular were at the forefront

of the progressive sect's agenda. The Northcoast Environmental

Center opened the same year as Humboldt Open Door, in 1971. Both

nonprofits are celebrating their 35th anniversaries and both

are at a moment of change.

It

wasn't just the clinic that was making strides at the time. The

first wave of liberal activists were infiltrating Arcata and

rattling cages over everything from the Vietnam War to bike paths

through the city. America was in the midst of an energy crisis,

and environmental issues in particular were at the forefront

of the progressive sect's agenda. The Northcoast Environmental

Center opened the same year as Humboldt Open Door, in 1971. Both

nonprofits are celebrating their 35th anniversaries and both

are at a moment of change.

"There

was a schism between the women's health and general medical,"

she said. "It became two separate entities and there were

bad feelings. I didn't want to see it split."

"There

was a schism between the women's health and general medical,"

she said. "It became two separate entities and there were

bad feelings. I didn't want to see it split." Within

that first year Spetzler's primary role was to improve Open Door's

infrastructure. The clinic was fitted with new sinks, a loft

was set up and exam rooms were built for more privacy. "We

needed to make it a more acceptable place," Spetzler said.

"It was really not a place where grandmas and grandpas would

want to go. It only served people like us, the counter-culture

population."

Within

that first year Spetzler's primary role was to improve Open Door's

infrastructure. The clinic was fitted with new sinks, a loft

was set up and exam rooms were built for more privacy. "We

needed to make it a more acceptable place," Spetzler said.

"It was really not a place where grandmas and grandpas would

want to go. It only served people like us, the counter-culture

population." One

way Spetzler plans to tackle this issue is by reaching out to

urban doctors who have already retired. If they could be lured

to the North Coast with offers of a high quality of life -- fishing,

golfing, arts, clean air, cheap housing (by California's standards)

and no traffic -- they might be willing to come out of retirement

to work part-time at a community health clinic. The additional

upside, as Spetzler sees it, is that the physician will no longer

toil with administrative duties, like billing, that overwhelm

a private practice.

One

way Spetzler plans to tackle this issue is by reaching out to

urban doctors who have already retired. If they could be lured

to the North Coast with offers of a high quality of life -- fishing,

golfing, arts, clean air, cheap housing (by California's standards)

and no traffic -- they might be willing to come out of retirement

to work part-time at a community health clinic. The additional

upside, as Spetzler sees it, is that the physician will no longer

toil with administrative duties, like billing, that overwhelm

a private practice. Over

the years, Bell and Spetzler have grown close, sharing ideas

about Open Door's objective, and agreeing that the key to their

success would be to provide the best quality of care, going beyond

the bare basics typically expected of community clinics.

Over

the years, Bell and Spetzler have grown close, sharing ideas

about Open Door's objective, and agreeing that the key to their

success would be to provide the best quality of care, going beyond

the bare basics typically expected of community clinics. Back at

his office, Spetzler seemed downtrodden by thoughts of his late

friend, Tim McKay, and perhaps was drawing parallels between

McKay and himself. Just a week before McKay died of a heart attack,

he and Spetzler met for lunch. The two men, graying, bearded,

big-bellied and just a year apart in age talked about what they'd

done with their lives, their activist careers and where they

were headed. Spetzler thought McKay needed to start passing the

reins to the next generation of Northcoast Environmental Center

workers.

Back at

his office, Spetzler seemed downtrodden by thoughts of his late

friend, Tim McKay, and perhaps was drawing parallels between

McKay and himself. Just a week before McKay died of a heart attack,

he and Spetzler met for lunch. The two men, graying, bearded,

big-bellied and just a year apart in age talked about what they'd

done with their lives, their activist careers and where they

were headed. Spetzler thought McKay needed to start passing the

reins to the next generation of Northcoast Environmental Center

workers.