News Blog

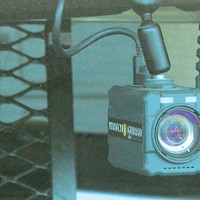

- photo by Thadeus Greenson

- Since 2008, the Eureka Police Department has outfitted all of its patrol cars with Watch Guard cameras. Who gets to see the footage they collect remains up for debate.

The city of Eureka is trying to keep its recent appellate court loss from setting a statewide precedent.

In July, the First District Court of Appeals rebuffed the city’s effort to block release of a video depicting the arrest of a 14-year-old suspect, ruling that the video — and others like it — could not be considered a confidential police officer personnel record, which receive special protections against public disclosure. The appellate court published the ruling, meaning it would become case law and set a precedent throughout the state.

But the city has now petitioned the state Supreme Court to depublish the July decision, which wouldn’t impact the court’s order that the specific video in question be released but would keep the decision from becoming case law and guiding future court rulings. And, in a rare move, on its own motion, the Supreme Court has extended its deadline for deciding whether to take up a full review of the appellate case — a review that would venture beyond the publication question.

The nuances of how this case meandered through the court system are somewhat complex, but the basics are as follows. On Dec. 6, 2012, Eureka police officers arrested a 14-year-old and one of the involved officers, Sgt. Adam Laird, was accused of using excessive force and criminally charged with assault. In court, Laird argued that he acted reasonably but that his fellow officers essentially set him up and withheld evidence of his innocence from prosecutors. Laird ultimately retired from EPD after settling a claim he brought against the city alleging that the city violated his rights in its handling of the case. He now works as a local private investigator.

The juvenile’s arrest, meanwhile, was captured on the dash-mounted video recording device in one of the responding EPD patrol cars. After the criminal case against Laird was dismissed, the Journal submitted a California Public Records Act Request asking for a copy of the video — a request the city denied, citing the discretionary exemptions for police investigative files and personnel records. The Journal then filed a petition in juvenile court under Welfare and Institutions Code 827, which carves out a process for members of the public to access juvenile court records.

On May 21, 2015, Humboldt County Superior Court Judge Christopher Wilson granted the Journal’s petition, finding the public interest in releasing the video outweighed any privacy concerns, and ordered the video released. The city then appealed, arguing Wilson erred in his ruling and his interpretation of the law.

Some 14 months later, the appellate court decided that Wilson got it right, finding that the video “is simply a visual record of the minor’s arrest” and couldn’t be considered a confidential police officer's personnel record as it wasn’t generated as a part of a process to review or discipline an officer. The city’s argument to the contrary, the court stated, “would improperly sweep virtually all [police videos] into the protected category of personnel records.”

- Day-Wilson.

“The case may confuse the bench and the bar by creating the appearance the Welfare and institutions Code section 827 sidesteps the protections of Pitchess,” Day-Wilson wrote.

As to the incomplete record, under appellate rules the appealing party is responsible for providing the court with a record of all the lower court filings and proceedings that led to the decision being appealed. In this case, Day-Wilson was unable to locate and obtain a transcript from one of the court appearances before Judge Wilson. “The opinion was reached based upon an incomplete factual record, and the lack of a complete record undercuts its reasoning,” Day-Wilson wrote.

The Supreme Court received letters from five entities opposing the city’s depublication request: the Journal, the American Civil Liberties Union’s California affiliates, the California Newspaper Publisher’s Association (CNPA), Arcata attorney and Executive Director of the Humboldt Center for Constitutional Rights Jeffrey Schwartz and Californians Aware, a nonprofit largely dedicated to increasing access to public information. (Click the hyperlinks to read each entity’s letter.) The city saw no letters submitted by outside entities supporting its request.

The letters opposing the city's request combine to argue that the appellate court’s ruling was accurate and valuable, and that depublication would have broad impacts.

Schwartz and the CNPA, which represents nearly 1,400 newspapers throughout the state, argued that depublication of the opinion would encourage police agencies throughout the state to sweep all police videos under the umbrella of confidential police officer personnel records, which could shield public access and tie up the courts.

As to the city’s argument that the opinion creates confusion by failing to address the interplay between laws governing the release of juvenile court information and those protecting police officer personnel records, Californians Aware argues there is no confusion at all. The court determined the arrest video “was generated independently and in advance of the administrative investigation” and concluded the video can’t be considered a confidential personnel record that would warrant Pitchess protections, Terry Francke, the nonprofit’s general counsel, writes.

“The city of Eureka, in requesting depublication, does not take issue with these conclusions but instead ignores them,” Francke writes.

As to Day-Wilson’s charge that the missing transcript undermines the court’s opinion, Paul Nicholas Boylan, a Davis attorney representing the Journal, points out that it’s the appealing party’s responsibility to provide the court with the record. If a transcript was missing, it was the city’s responsibility to either find it or take other steps to provide the court with the information it would have contained.

Meanwhile, the ACLU used Day-Wilson’s own words against her, pointing out that she’d argued before the appellate court that the missing transcript was “irrelevant” because this was a matter of “statutory interpretation.”

“The city should not be permitted to take the position before the Court of Appeal that the facts are irrelevant and no factual submissions are necessary, and then request depublication of an unfavorable decision on grounds that the court did not have all the facts,” the ACLU writes.

“To the extent that the opinion discussed any factual background,” the ACLU’s letter continues, “it was the undisputed manner and purpose for which the video was generated — independently and in advance of the ensuing administrative investigation — that the court found dispositive as a matter of law. Nothing in the transcript could alter that basic fact or undermine the conclusion that followed.”

Back in August, we reported that the city had already spent at least $7,683 appealing Wilsons’ ruling, in addition to an unknown amount of staff time. If the appellate ruling stands, it also allows Boylan, the Journal’s attorney, to recoup his costs and fees from the city.

Days after the appellate ruling, Boylan sent Day-Wilson an email urging her not to take the matter any further.

“I am not posturing when I say that, should you appeal this further, you won’t win,” Boylan wrote. “Although anything is possible, a reversal of the Appellate Court’s opinion is extremely unlikely for a bunch of procedural and substantive reasons. Further appeal will do nothing but waste more public employee time and more taxpayer money. Further litigation will only drive up the fees and costs the city will inevitably be ordered to pay.”

It’s worth noting that the case has only been agendized once for closed session discussion with the Eureka City Council since the appellate court’s ruling, and the council announced no final action. It’s unclear who ultimately decided to pursue depublication. Councilmembers Linda Atkins, Marian Brady and Kim Bergel declined to comment on the matter, as did Mayor Frank Jager. Councilmembers Natalie Arroyo and Melinda Ciarabellini didn’t return Journal calls seeking comment.

In an email responding to the Journal’s inquiry as to who made the call to pursue depublication, City Manager Greg Sparks said the city attorney told him not to respond because the case “is in litigation and could not be commented upon.” Day-Wilson did not respond to a Journal email seeking comment.

Under its motion, the Supreme Court has until Nov. 17 to decide how to proceed with the case.

For more on the appellate case, see past Journal coverage here and here. And to track the case as it proceeds on the Supreme Court docket, click here.

Comments