News Blog

Bayer Pulling Controversial Birth Control Device from U.S. Market, Bringing Some Closure to a Local Woman's Fight

- Photo courtesy of Tamara Meyers

- Myers, 38, took a moment just before her hysterectomy operation in June of 2014 to pose for a photo.

Bayer said the move is entirely based on declining sales revenue and a determination that the Essure business is no longer viable, but the company says it stands by the safety and effectiveness of the device. The U.S. is the last country in which Essure is being sold, meaning the device will no longer be available anywhere after Bayer halts sales at the end of this year.

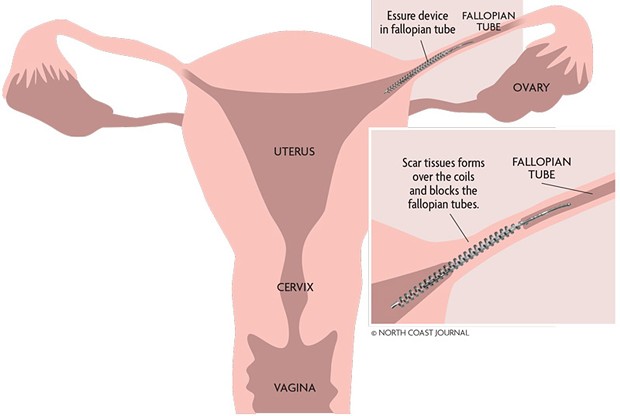

Billed as offering patients a nonsurgical, non-hormonal alternative to tubal ligation sterilizations, Essure is made up of two 2-inch-long metal coils — one nickel titanium alloy, the other stainless steel — wrapped around polyester fibers. Using a scope device that enters the uterus through the vagina, a doctor implants one coil in each of the openings of a woman’s fallopian tubes (see the diagram at the bottom of this post). There, the coils are designed to induce inflammation — an immune response as the body attempts to reject them. Over the course of three months following implantation, scar tissue — or a “natural barrier,” as Bayer puts it — builds up around the coils, blocking the fallopian tubes and thus the ability of sperm to fertilize a woman’s eggs.

- Courtesy of Bayer

- The Essure contraception device.

In an email to the Journal, Myers celebrated the good news, said she’ll always be grateful that sharing her story helped deter some women from considering Essure and that her and other “E-sisters’” efforts have resulted in the device being pulled from the market. She also noted that Bayer’s decision comes as a new documentary about Essure, The Bleeding Edge, is set to be released on Netflix on July 27 and will profile the Essure Problems group, which Myers is a part of, and issues with the regulatory process that allowed Essure to be approved for sales initially.

Read more about Myers and her story here. And See the Los Angeles Times’ full report on Bayer’s decision here.

- North Coast Journal Graphic

- An illustration of how Essure is supposed to work.

Comments