News Blog

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Photo courtesy of Greg Rumney

- A rescue boat sets out near Alton.

Editor’s Note: Five years ago, the North Coast Journal told the stories of heroism, hope, tragedy, strength and survival that took place during the Flood of 1964 to mark its 50th anniversary. Here’s a look back at those accounts as Humboldt County commemorates 55 years since the water rose, forever changing lives and the region’s landscape.

It had been dubbed the flood of the century, when the rain came down in sheets in 1955 and Humboldt County's rivers rose to gobble homes and towns. Nine years later, it happened again, but worse.

By the start of December 1964, Humboldt was already wet. A series of storms in November had left the ground saturated and the rivers full. Higher elevations were experiencing a near-unprecedented amount of snow for so early in the season. The conditions were perfect.

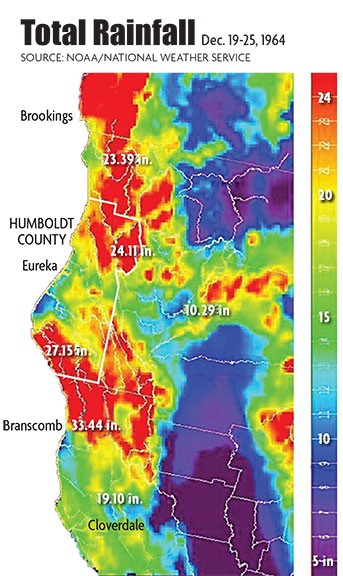

Reginald Kennedy, a service hydrologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's station on Woodley Island, explained that in mid-December a storm 500 miles wide, extending from near Hawaii to the coasts of Oregon and Northern California, reached shore. "The combination of this very moist warm air, strong west-southwest winds and orographic lift of the mountain ranges oriented at nearly right angles to the flow of the air resulted in heavy rain" through Dec. 23. "Today, we use the term atmospheric river to describe this type of weather phenomenon."

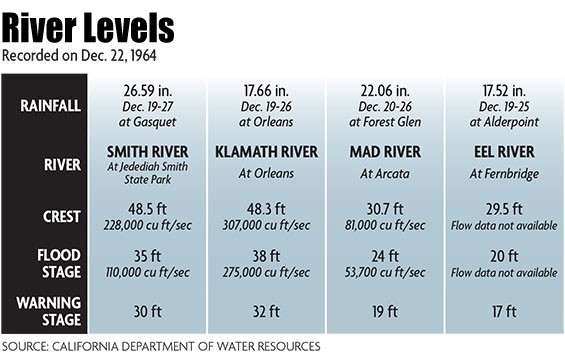

"The Dec. 19-23 storm was of unprecedented intensity in the region," states a California Department of Water Resources report, noting that Ettersburg on the Mattole River registered a staggering 50 inches of rain during the period, including 15 inches on Dec. 22 alone. Standish-Hickey State Recreation Area recorded 22 inches of rain in a single 24-hour period during the onslaught. (That's more rain than Eureka recorded last year.)

The warm storm also raised the freezing level to 10,000 feet, meaning buckets of warm rainfall were coming down onto the near-record November snowpack. This sent fresh snowmelt rushing down into local rivers, which quickly swelled, rising 18 inches an hour in some places. Daily discharge measurements taken at the mouth of the Eel River show flows increased from less than 10,000 cubic feet per second on Dec. 19 to nearly 700,000 cubic feet per second the following week.

The results were catastrophic.

- Photo courtesy of Greg Rumney

- Pete's Grocery sits underwater, along with the rest of Pepperwood, which was washed out when the Eel River crested its banks.

- North Coast Journal/NOAA

- River levels recorded on Dec. 22, 1964.

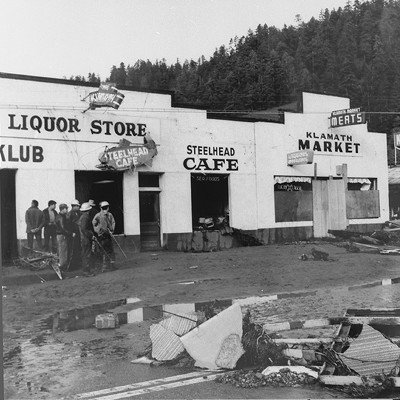

At Miranda, the high-water mark reached 46 feet. The town of Klamath was covered by 15 feet of water. Riverside towns like Orleans, Myers Flat, Weott, South Fork, Shively, Pepperwood, Stafford and Ti-Bar were decimated, while Metropolitan, Rio Dell, Scotia and Ferndale were heavily damaged.

In total, more than 10 million acre feet of water was discharged into the Pacific Ocean from the North Coast's rivers and streams between Dec. 20 and Dec. 26.

Logging camps were wiped out by the onslaught of water, which also breached the Pacific Lumber Company's log pond in Scotia, sending thousands of old growth logs barreling downriver. Massive logjams battered everything in their path, knocking homes off foundations and taking out bridges on their way out to sea. More than a dozen bridges in Humboldt County were destroyed; Fernbridge was the county's only major water crossing to survive the flood.

Across the North Coast, 24 people died, including 19 in Humboldt County, where another 1,200 were injured. The county recorded more than $53 million in damage — including $14 million to state highways, $12 million to county roads and buildings, and $23 million to private property. Some $4 million was spent after the flood simply on cleaning up debris, according to the California Department of Water Resources report.

In the aftermath of the flood, Humboldt Beacon correspondent Lillian Sarginson described what she saw as the untold story amid all the detailed accounts of the wreckage, loss and strife. "Thinking has been blurred ever since Monday, Dec. 21, when Mother Nature raised an angry fist and delivered her knock-out blow to Northern California," Sarginson wrote.

"By now everyone knows how great a disaster has befallen this area. The inconceivable force of water in its mad dash to the sea, the fear that spread with equal speed into the hearts of all in the path of such fury. There is another side of the story: friends. The wonderful people who rally to aid the distressed."

Accounts of the flood are rife with heroism, bravery and kindness as a region banded together to make it through. Life magazine correspondent Jack Fincher led a team of seven reporters and photographers into Humboldt County to cover the flood and walked away impressed by a community of ranchers, loggers and lumbermen who were ready to roll up their sleeves and help their neighbors. In his story, "A Lovely Land Laid Waste by Water," he wrote of a self-sufficient group who simply opened their freezers — which were made useless by power outages anyway — and feasted on dinners of fried chicken, stew, steak and lasagna, while directing help to those who needed it most.

"What a lot of the outside world doesn't realize is that many people are marooned but, in most instances, not needy unless they've lost their homes," Fincher wrote. "It's pretty frustrating to an Army helicopter team to brave the wind-swept summit of a mountain, as ours did, to get to the valley on the other side and be told by a well-meaning ranger, 'We don't need this stuff. We're cut off but we got all we need. Now there are some people over on the other ridge. ...' And the copter heads over there, through low-scudding wisps of cloud and dangerous utility wires, only to be told the same thing. It's not that the people aren't grateful, it's only that they're convinced someone just over the hill must have it worse than they do."

In recent weeks, the Journal caught up with a handful of people who were here when the waters rose. These are their stories of loss, survival and service.

Thadeus Greenson

‘You Weren’t Afraid to Cry’

Frances Rapin's car was packed with Christmas presents for her family — the 44-year-old was leaving for Marysville, Washington, where her brother lived, until she heard the bridge was out.Soon after, Rapin, who worked for the Belcher Abstract Title Company, was enlisted to bring her knowledge of Humboldt County's terrain to a hastily gathered helicopter coordination center.

Rapin (who went by Allen at the time) gathered large maps of the flooding watersheds, and, along with a Navy Admiral, two Army colonels and a host of military and civilian personnel, took over the district attorney's office in the county courthouse. Volunteers brought in short wave radios, and Rapin helped direct pilots to the rescue calls flooding in from the Eel, Van Duzen, Klamath and Trinity river basins.

"We were taking incoming calls from various organizations and outposts and trying to get choppers to the right areas," says Rapin, who's turning 94 this month.

One call, from the Hoopa or Orleans area, was so full of cuss words Rapin won't repeat it, but the message was clear. "'Keep the politicians on the ground in Eureka. Send us milk for kids and medicine,'" she recalls the person saying. "They were pretty desperate up there. There was no way getting in or out."

For weeks, she and others spent long days coordinating rescue efforts, putting out-of-town military pilots in touch with local spotters familiar with Humboldt County. The rescue effort wasn't without tragedy. Two helicopter crashes — one north of Trinidad and another along the Eel River — killed 11 people, including former county Supervisor Bunny Hadley. Only the pilot in the Southern Humboldt crash survived.

"We all suffered a loss with the boys that were killed," Rapin says, her eyes glossing with tears. "You weren't afraid to cry over that. When we got word a chopper was down we all held our breath."

Even harder was seeing the devastation from the air, she says — particularly the remains of Christmas packaging and presents in the trees surrounding the destroyed riverside towns.

But everyone chipped in, Rapin says. Restaurants donated food to the rescue workers, volunteers sprang up everywhere and her former employer continued to pay her — even though she spent most of those days at the command center. "It was just a lot of cooperation between a lot of people."

And her brother's presents? Delivered by an army pilot flying north to Washington.

Grant Scott-Goforth

'There Will Be No Rescue'

Marvin Goss was an 18-year-old freshman at Humboldt State University, having just completed his first semester in December 1964. He was also studying to get his private pilot's license and needed to pass just one final flight test to reach his goal. With the flight scheduled for just a few days after school let out, he said goodbye to his peers and put off returning to his family's South San Francisco home and stayed on campus."I just wanted to get that certificate, then I could jump on a bus and be home for the holidays," Goss recalls. "It was not to be."

The trouble was the test kept getting postponed as the weather didn't cooperate.

The rain just wouldn't let up, and Goss' days-long wait turned to weeks. By Christmas Eve, the bridges had washed out and Goss was stranded, so he and the small handful of students still in the dorms sat down to dinner with the resident manager.

It was over dinner, Goss says, that the manager mentioned that officials were putting together a search party, explaining that a rescue helicopter carrying seven people had crashed in high winds and rain east of Big Lagoon on the afternoon of Dec. 22. The helicopter and its crew had been plucking stranded families off rooftops in the Eel River Valley and flying them to safety amid wind gusts of up to 100 mph. The chopper had just completed a successful rescue when — piloted by Lt. Donald Prince and co-pilot sub Lt. Allen L. Alltree, with Petty Officer Second Class James Ninger Jr. on board — it left the airport in McKinleyville shortly after 4 p.m. to return to Ferndale.

There, the helicopter and its crew picked up four stranded civilians — Arnold "Bud" Hansen, Marie Bahnsen, Betty Kemp and Kemp's 20-month-old daughter, Melanie. Officials lost radio contact with the crew at about 6:30 p.m.

Goss can't recall exactly how much of this he knew, but he quickly volunteered to help with the rescue effort, believing that, with a background in mountaineering and backpacking, he could be of some use. There were about 200 people in the rescue team that set out on a steep, rugged swath of logged Louisiana Pacific property filled with heavy brush. The group spread out, Goss says, and started making its way up the hillside.

"It was a bushwack," he recalls, adding that it was torrential rain with high winds.

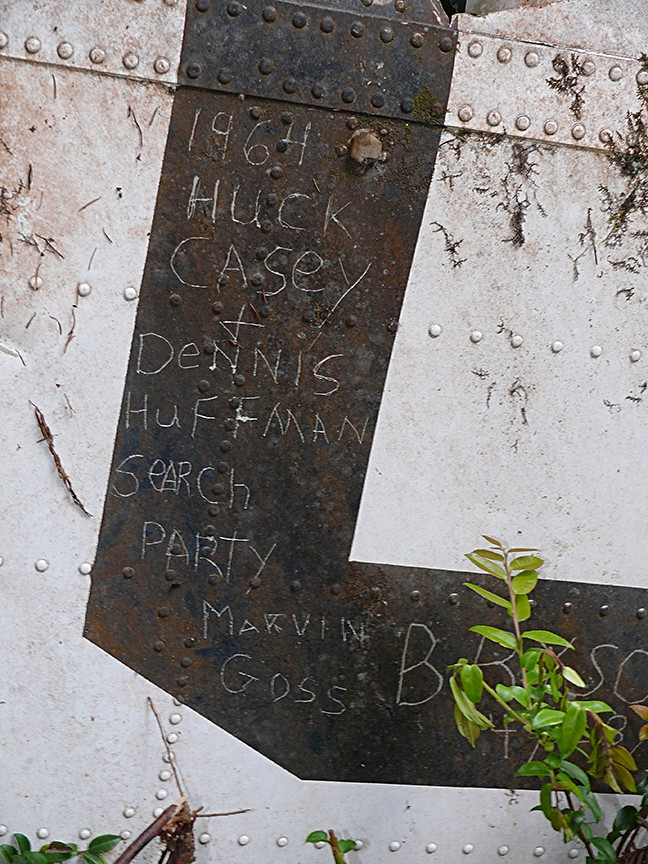

The crew had made it about a mile and was nearing the top of the ridge, Goss says, when the thunder and lightning grew heavy. A smell of kerosene permeated the air and Goss recalls someone saying they were getting close. Then someone shouted to stop and wait. Goss says he was standing, drenched to the bone in a steady downpour, when one of the leaders came back. "The search is successful," he said. "But there will be no rescue."

The crew and its passengers didn't survive.

- Photo courtesy of Greg Rumney

- After finding the U.S. Coast Guard Helicopter that crashed during a rescue effort, killing all seven aboard, members of the search party signed a piece of the wreckage.

- Photo courtesy of Greg Rumney

- After finding the U.S. Coast Guard Helicopter that crashed during a rescue effort, killing all seven aboard, members of the search party signed a piece of the wreckage.

It wasn't until more than a week later that Goss finally got home, having hitched a ride with a travelling salesman east over State Route 299 to Redding, where he caught a bus. The experience proved to be a formative one for Goss. HSU canceled the following semester and, fearing he'd be drafted into the Army to join the Vietnam War, Goss signed up for the Air Force where he went to technical school to study weather observation. When he finally came back to Humboldt a few years later on the GI Bill, Goss got his masters degree in watershed management. "I focused on rainfall," he says.

Thadeus Greenson

‘Surrounded by the Eel’

On Dec. 21, the Eel really started coming up, and water sloshed over the threshold of 14-year-old Ginger Leonardo's house at the Leonardo & Nunes Dairy on Grizzly Bluff Road. Ginger's mom, Gerry Leonardo, and her aunt Lily Nunes, who lived next door, kept sweeping the water back out, repeating the weatherman's words they'd just heard on the radio: "The river is receding."The families had been warned they needed to evacuate, but they weren't too worried; the Leonardos' house had burned a few years after the 1955 flood and was rebuilt on higher ground, above flood-stage they were assured. But Ginger's dad, Tony, and a hired hand from Portugal went over to her aunt and uncle's place to help Uncle John haul furniture up to their second floor. After that they moved all of the animals into the big barn, locked them in the stanchions and loaded them up with hay and grain.

Then both families holed up in the Leonardos' house. The water kept rising.

The next day, the middle of the floor buckled. "There were Christmas decorations on the coffee table," recalls Ginger (whose married name is Nunes), "and we watched as it slipped over and the decorations fell off. My dad yelled at my mom to get me and my sister up into the attic."

Her sister, Tina, who was 6, had cerebral palsy and was in a wheelchair. They struggled through the narrow opening into the attic. When the water rose to the light switches, the rest of the family members went up. For three days and two nights, the 10 of them huddled there on two small sheets of plywood. The space was shallow and they couldn't stand. They took turns lying down to rest. Ginger fretted about her prom dress and wanted to leave the attic to retrieve it. "Leave the damned dress!" her mom told her.

They ate the food Ginger had helped her mom and aunt prepare, but it wasn't enough.

"My mom told Daddy he had to go down and hunt up something to eat, so he went down," recalls Ginger. "He was gone awhile, and when he came back up he had a can of fruit cocktail and a nail. My dad, he was always loud, but he tried to be quiet and he whispered to my mom that the walls were bulging in and he was afraid if he opened a cupboard the whole wall would come down. And he told her he was afraid we weren't going to make it. So then we all started screaming." Her mother reassured them.

Tony Sr. opened the can with the nail and they shared its contents. Down below, two of their dogs clung to mattresses in the water; a third jumped out the window and disappeared. The house creaked and the water rushed loudly all around. Upstream, Pacific Lumber Co.'s log pond had failed and now logs started battering the house and piling up. Then one crashed through a window.

Uncle John had cut a hole in the roof so they could see what was happening: It looked like an ocean out there, with debris poking up out of the foaming waves. They watched Tony Sr.'s old Desoto float away. Animals bobbed by. The barn somehow stayed together, but its floor boards weren't nailed down and floated with the rising waters. The family's 150 cows either drowned or broke their necks in the stanchions as the floor gave out underneath them.

One of the nights, the rain gone and the moon bright, Uncle John was looking out of the hole in the roof and saw his house fall away. He collapsed, one arm punching through sheetrock and his face splitting open on a two-by-four. Ginger recalls her dad lighting makeshift flares made of wax and newspaper and dropping them from the attic at night to see how high the water had crept.

A plane flew overhead one day. The family watched as boats tried to get to them from the Ferndale side; the water was too swift. Finally, on Christmas Eve around 3:30 p.m., two boats from the Fortuna side reached the house and, one of them nearly capsizing, brought the family to safety.

Heidi Walters

'Waiting on Their Roofs'

Scott was a captain and company commander for the Eureka unit of the Army Reserve 250th Transportation Company. On Dec. 19, he got orders from company headquarters in the Presidio — he was to mobilize 20 of the unit's best drivers and conduct rescues with the reserve's DUKWs, or "Ducks."

- Photo courtesy of Greg Rumney

- The Army Reserve used DUKWs, or “Ducks,” to rescue people stranded on rooftops and boat them to safety.

The local reserve had 27 of the amphibious trucks (the same vehicles that brought American troops on shore at the WWII invasion of Omaha Beach).

"Our primary goal was to rescue people from homes or high ground or roofs of homes," Scott says, but the swiftness and sheer volume of water made that immediately difficult. "The DUKWs really were not seaworthy in swift water. I was always afraid of losing a DUKW — and if you lose a DUKW you might lose somebody. So I always had three together so one could pull another one out."

The first day, Scott and men from his unit headed south from Fortuna with orders to deliver blankets, medicine and water to Scotia and Rio Dell. But the bridge north of Rio Dell was out, and the water was too swift for the DUKWs. The southern communities of the Eel River — many of the hardest hit — would be only accessible by helicopter for some time.

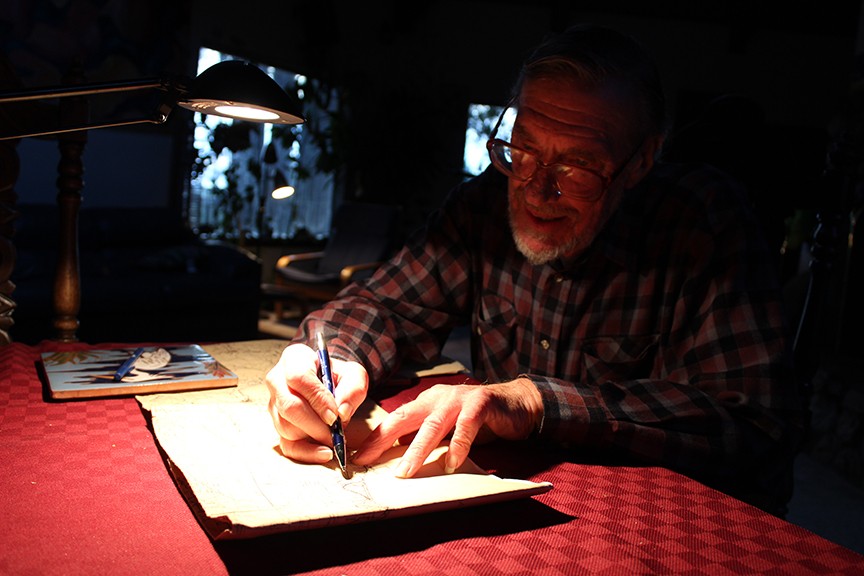

- Photo by Grant Scott-Goforth

- Jeremiah Scott, whose Army Reserve unit drove amphibious trucks to stranded residents during the flood, looks through a retrospective published in 1965 in his Eureka office.

Scott and his drivers turned back north, hoping to cut through Ferndale and up and over the ridge on Blue Slide Road into Rio Dell.

But, he says, "I got to Fernbridge and it was just a sea of water all the way over to Ferndale. ... I thought I could go into the water with DUKWs, but the water was so swift on the other side of the bridge that I was fearful that the water would just take those DUKWs sideways and they'd end up in the ocean."

By the second or third day, the water had receded enough for Scott's unit to cross the bridge, where they spent the next several days rescuing people in the Ferndale area.

"I can recall going out into the Eel River Valley to houses surrounded by water with people waiting on the roofs," Scott says. "We had ladders so we got women and children off the roofs or off the high portions of the buildings. ... I can't say with certainty the number but I would say several hundred."

Grant Scott-Goforth

‘Weymouth Bluff’

It was already a chaotic, and sad, December for Calvin Shultz' great-grandpa Carl Briceland. Earlier that year, he and his wife, Mary, had sold their Ettersburg ranch and moved to Weymouth Bluff, overlooking the Eel River Valley east of Ferndale, to retire. About a week before Christmas, Mary died in a car wreck on the way to go Christmas shopping in Fortuna. Carl held a funeral, and a few days later came the flood.

Shultz, who was just 8 and lived in Fortuna with his folks, remembers going over to stay for three weeks with his great-grandpa in the aftermath of the flood. Other peoples' cows were milling around the bluff because Carl had let some of the ranchers down in the bottoms bring their animals up earlier in the week.

"There were cows all over the place," Shultz says, "and nobody could get up there to feed them so they had to find their own way. And we had no water at the house, no nothing. I remember the old man saddled up the old horse, Tipi, and rode to Ferndale for groceries, cutting fences to get through."

- Photo by Heidi Walters

- Calvin Shultz lives atop Weymouth Bluff on the land his great-grandparents Carl and Mary Briceland retired to just months before the 1964 flood. He was 8 at the time, and remembers how his great-grandpa let lowland ranchers bring their cows up to the bluff to escape the flooding.

Months later, Shultz says he went with his dad down to the Loleta bottoms where men were salvaging redwood trees and logs that had washed down from Pacific Lumber Co.'s woods and log pond into the ocean and then been "thrown back from the ocean" onto the land.

"There were huge piles of debris all along the Loleta bottoms," Shultz says.

He was just a boy, so he wasn't actively salvaging himself. His dad was. And he heard that some folks were even bit by rattlesnakes coiled among the log debris — they had been washed out of the mountains, too, along with the trees.

Heidi Walters

Flying Home

Dave Stockton heard rumors that his dad had drowned when the swollen Eel River swept over Holmes Flat and the family farm. But Stockton, who was 21 at the time and working his way through college in Redding, didn't believe it. His dad was a survivor. But he had to get home to find out. Plus, it was Christmas.The roads into Humboldt were all closed. So Stockton, his roommate Colin Bazzi and a guy from Eureka with a puppy pooled their money to hire charter pilot Dave Cavanaugh to fly them. It was Christmas Eve, raining hard but shirt-sleeves warm. And here came Cavanaugh, landing, brakes failing, skittering off the airstrip.

"I said, 'I'm not going,'" recalls Stockton.

- Thadeus Greenson

- Marvin Goss was an 18-year-old freshman at Humboldt State University when he joined a rescue effort to search for seven people who crashed in a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter east of Big Lagoon.

Stockton's friend Al Hahn, a mechanic at the airport, said, "Aw shut up and help me." The men pulled the plane back onto the tarmac, and Hahn made a minor fix.

They flew into the storm, the puppy balancing on a suitcase on the Eureka kid's lap.

Cavanaugh frequently lifted the small plane above the storm, and when it started to freeze, he dropped it back below the clouds. They were all getting sick. It took an hour and a half to fly the 60 miles to the Rohnerville airstrip; Cavanaugh zipped back to Redding in 32 minutes, says Stockton.

Then Stockton got on a Cessna piloted by his friend Richard Bullock, who was taxiing people between Rohnerville, Scotia and Dyerville.

"It was starting to get dusk, and we came right down the Eel River Canyon," recalls Stockton. "We flew over all this devastation. Pepperwood and Shively were just horrible. Big mess. It was pretty depressing."

Pepperwood's buildings were jammed up against a long row of young redwood trees planted by "Papa" St. John. At Dyerville the Cessna banked steeply and descended fast to land on the freeway bridge, the temporary landing strip.

Stockton asked about his dad. His family home, flooded 12-feet-deep, had been lifted by the river and turned sideways. His dad had got out and driven away but then returned for the dog, who was adrift on a piece of firewood. He had a narrow escape, but was fine. Everyone in Holmes got out but five died in a hotel in Pepperwood.

Heidi Walters

'Captain Courageous'

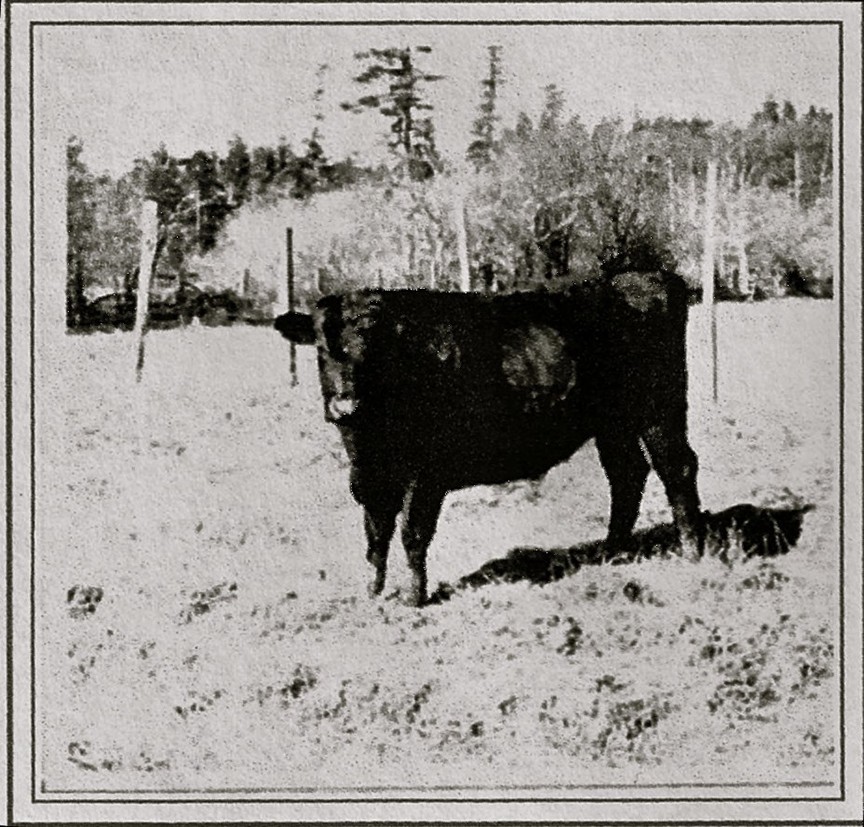

The flood waters were devastating to local cattle herds, with thousands of cows drowned in barns, swept down river or left to starve in swampy flood plains. Many were swept out to see only to wash back up on local beaches, where they lay in "bloated lumps," as one reporter put it. But amid the carnage, one Angus steer's tale offered hope and he became a symbol of perserverence and survival for the decimated town of Klamath.Raised by 15-year-old Brad Hale from a "weak little calf," according to a story by Andrew Genzoli, Bahamas was in his pasture at the Hale Ranch in Klamath Glen when the waters rose and he was washed into the engorged Klamath River and rushed 2 miles out to sea.

But the steer apparently grappled atop a debris pile, and managed to stay above water. In the aftermath of the flood, as logjams washed back to shore and clogged Crescent City Harbor, fishermen "observed a movement in the debris, and discovered the Angus," according to Genzoli's report. "It was a dangerous task to remove the animal, but carefully, they did." Don Ford, hailed as Bahamas' chief rescuer, received a medal of honor for compassion and bravery from the American Humane Society for his efforts.

- Photo courtesy of the Klamath Chamber of Commerce

- Tough beef: The steer known as 'Captain Courageous.'

Bahamas' tale of survival captured the hearts of the flood-ravaged region, and newspaper reports wrote the animal's story with verve under headlines like "Bullish Miracle" and "Captain Courageous." Bahamas went on to live almost two decades before his death in December 1983, having lived a life of leisure and fame. The Klamath Chamber of Commerce purchased the animal after the flood, and every spring would move him down to a specially built corral in the old Klamath town site, where "all manner of goodies are bestowed upon him by friends, former neighbors and summer tourists."

Thadeus Greenson

- North Coast Journal/NOAA/NWS

- Total rainfall, Dec. 19-25, 1964.

The Old Photo Guy

Greg Rumney was a student at Humboldt State University working part-time at PhotoWorld when he crossed paths with Rudy Gillard, who owned Gillard Photography down in Fortuna. "He kind of pulled me out of the crowd," Rumney recalls, explaining that the two soon teamed up on Chromogenics Photography.When Gillard retired in 1997, he gave Rumney all his old photographs and signed over the copyrights. The collection — which filled two long-bed pickup trucks — included scores of old flood photos Gillard had taken as an official state photographer, and became the foundation of Rumney's business collecting historic images and selling prints as the Old Photo Guy. Now boxes of old photos show up unannounced on Rumney's porch, and the collection has grown to include more than 70,000 images.

But the flood stuff kept calling to Rumney. "This thing just kind of grabbed hold of me," he says. "It became like a bad drug. I just couldn't put it down. The more I looked into it, the more I wanted to learn." Rumney recently teamed up with local historian Dave Stockton to put out a book, The 1964 Flood of Humboldt and Del Norte, which was so popular it went into its second printing 17 days after its release.

Rumney's now busy working on a documentary, "The Angry Eel: True Tales of Hell and High Water," that will relay the river's flood-laden past, from 1862 through 1997. Rumney opened his photo collection up to the Journal for this story.

Comments