According to some estimates, nearly 900 billion photos will be taken in 2014. By the time you finish this paragraph, more than 200,000 photographs will have been uploaded to Facebook alone. Local photographer Suk Choo Kim certainly adds his fair share to these numbers. He estimates that he snaps more than 100,000 photos a year, every year. Digital photography allows him to click the shutter at will without having to process negatives, but just like every photographer, he still has to sort through each image to find which ones worked and which ones get tossed.

So what makes the cut? How does Kim whittle away 95 percent of his shots to find the best ones? In advance of his upcoming show, 2014, at his Upstairs Gallery, I got to ask him that question at his home studio in rainy Bayside. Shelves abound with archival boxes and framed works. A massive computer screen is ringed with stacks of printed photos. Sitting on a tall stool, Kim's round cheeks break into a smile as he lays down his theory on what makes a good photo.

First, he says, is the concept of previsualization — conjuring the image in your head before snapping the shot. Kim considers technical factors like lighting and exposure ahead of time, allowing him maximum control from the moment he puts the camera to his eye. Sure, he'll do some editing on the computer (as photographers still do in darkrooms), but the previsualization process plans for it rather than reacting to accidents later.

Second, says Kim, "you have to start with a good subject." This is perhaps the most important element in creating an excellent photograph. "Most people think their children are great subject matter," he says with a chuckle, but outside of immediate family, others may disagree. The imagery has to tell a story, "not about yourself, but about what you are taking the picture of." If you think about the iconic images of our time: Widener's Tiananmen Square "Tank Man," or Lange's "Destitute Mother," for example, they present us with a past, present, and future all at once. "If it has a compelling story," notes Kim, "peoples' interest goes right there."

For Kim, the power of a photo to activate our minds is a "prerequisite" for a good photo, but lighting can make or break a subject's strength. Dark photos create eerie moods, harsh lighting can be dramatic and the natural light of a landscape is calming. Without good lighting, the subject could be washed out, barely visible or simply flat and boring.

Along with light and subject, Kim looks for composition — how the subject is arranged in the image — among his thousands of shots. "If [the photo] is not compositionally correct," he warns, "it doesn't matter what the subject is, your eyes don't catch it." Is the landscape dwarfed by a massive blue sky, or is it a shot of a single, gnarled tree? Is that tree in the lower-left corner or placed squarely in the center? Composition is perhaps the most difficult element to master and one that readily reveals a photographer's style.

The final print is yet another element in crafting an excellent photo. This is why there are stacks and stacks of the same photograph piled up in Kim's studio. He goes through subtle adjustments in print after print, and it takes a trained eye to see the difference. Kim looks for a broad tonal range with details in the brightest highlights and darkest shadows, and he'll make many prints, at great cost, to ensure that everything is balanced.

Success in one or two of the elements described above makes for a good photograph, "but if you have three or more of those elements, it's going to be very good," he says. "I'm trying to put as much of those factors as possible into my imagery. When I have more than three of those, then I'd like to show that."

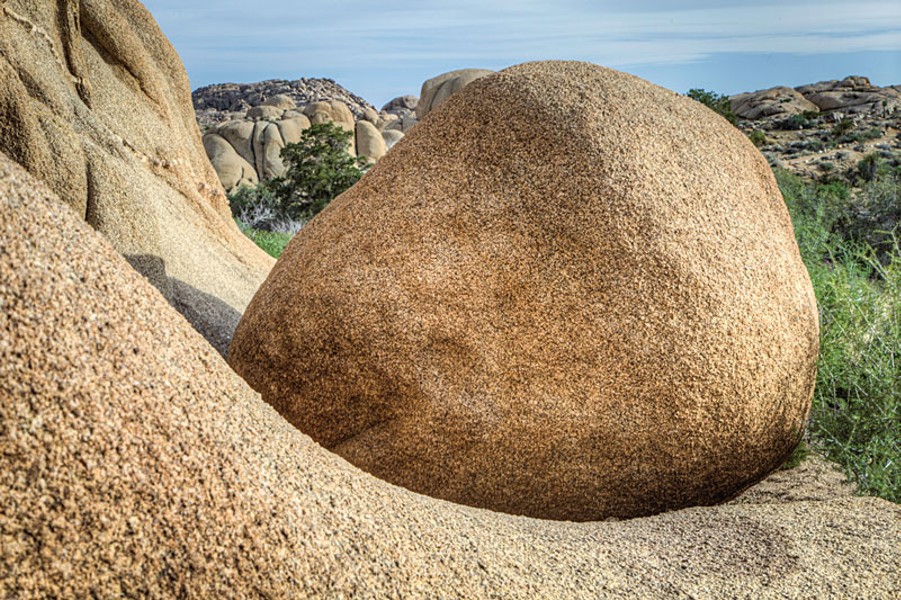

At his latest show, titled 2014, Kim has chosen some of his landscape photographs from the last year. Many of the shots were taken off the cuff, not fastidiously composed, as he traveled national parks throughout the west in search of vistas for a larger future exhibition. Kim's eye has found those facets of the landscape that describe a sense of place through the intrinsic features of stone, sand or sky. A boulder nestled in a crook of stone pops with texture and form. A rocky trail winds through something like a desolate moonscape. Rough cliffs circle a pebbled pad, the sun streaming in through an opening in canyon walls.

While all of the works in Kim's show meet his criteria, there's one more element: time. Sifting through thousands of shots, then editing and printing them means Kim regularly works late into the night. Forty-seven years of this has sharpened his focus and drives him on. "It's not just a thing," he says with a hint of sanguine surrender, "It's what I do. I make images every day."

Comments