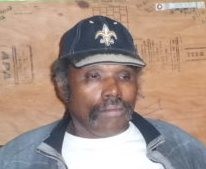

- Courtesy of Eureka police

- Reginald Clark

After a white supremacist couple on a murder spree careened into Eureka, police say, a man died because he was black. A man died because he was there.

The man's name was Reginald Alan Clark. His friends think he died partly because he had scraped a little something out of a hard life -- maybe the disability check he'd likely just received, or maybe the truck his killers coveted for their next getaway.

Clark, 53, had long saved for a down payment on that truck, the blue 1989 Ford where his body was found, said Tim Guyette of Eureka, who had been Clark's friend for 30 years.

For years, Clark had ridden a bicycle everywhere, Guyette said, to his shared studio apartment in Eureka, and to the St. Vincent de Paul soup kitchen where he regularly ate lunch. That bicycle lay in the back of the truck on Oct. 7, when police discovered Clark's body.

Clark was the fourth and final victim in a three-state rampage driven by family bad blood and racism, according to investigators. Police say that in his confession, David "Joey" Pederson proudly referred to Clark as "a negro with a bullet from my gun in his head." Officers believe that Pederson's girlfriend, Holly Ann Grigsby, tried several times on Oct. 4 to talk with different men outside Winco, a popular late night hang-out for the disenfranchised.

Then she approached Clark.

However random or deliberate, the killers had found a man remembered by his friends as both gregarious and deeply private, who navigated the world living on Social Security Disability and soup kitchen meals. Clark endured despite a heart condition, despite a past that included homelessness and low-income hotels. His friends say he never lost his sharp sense of humor or his ambition to improve his lot.

"Kids loved him," Guyette said. "He was gentle and respectful around women. He never cussed in front of a woman. He was never a player or gangster; he was a regular guy."

Clark came to Eureka from Chicago in the early 1980s, according to Guyette, and his first job here was washing pots and pans at St. Vincent de Paul.

Although he didn't marry, he was in a relationship long enough to become a father figure to the woman's children, said Guyette. "He treated those kids as if they were his kids."

One of them apparently laid flowers at the impromptu memorial that has sprung up on Glen Street, where Clark's body was found.

"A girl came and put flowers there and said she was his daughter, a very pretty girl in her twenties," said Jennifer Tulmau, the Glen Street resident who called police after noticing an odor coming out of Clark's truck.

The young woman could not be reached for comment.

According to Ayres Family Cremation, which is arranging a memorial service for Clark, he also leaves a sister from South Carolina and an uncle in Eureka.

In Eureka, Clark worked odd jobs, usually for friends, and talked about finding a career so he could get off Social Security. Guyette said that Clark was planning to go to truck-driving school. In the meantime, he was clean and hard-working, fond of football, the Saints and pro wrestling.

"He battled homelessness for a long time in Eureka, but he took care of himself, showered and wore clean clothes," Guyette said. "Many winters he had no place to go. Last winter he slept in my truck every night."

On a recent morning in Eureka's Old Town, several friends who often lunched with Clark at St. Vincent de Paul showed little emotion when talking about his death. It was as if they'd become accustomed to crime, and to loss. Only one, a muscled black man, was too disturbed to talk about the man he knew. "I don't want to talk about Reggie Clark," he said. "It'll just make me mad."

Others recalled that Clark, too, shied away from some conversations. He didn't talk about his health or the pacemaker that steadied his heart. Instead, he was social and witty, a jokester who laughed readily and spared women his dirtier jokes.

"Reggie was always cracking jokes," said David Little, 31, who'd known Clark for nearly 20 years. "He was great with the kids. I don't think I ever saw Reggie unhappy and I know he's been through some hard stuff. Reggie had a big heart and I know he touched a lot of people. He didn't deserve what he got from these people."

Now Little faces the challenge of telling his children, ages 5, 4 and 2, that their family friend is dead. "It's the first death that's close to us," he said.

The friends Clark made at the soup kitchen speculated that his newest bond there may have led to his death. They believe the killers also found their way to St. Vincent de Paul, ate there, and became at least familiar faces to Clark.

Billy Harlow, a St. Vincent de Paul volunteer, said he recognized a tattoo on Pederson's neck after his photos were published and is certain he had seen the killers come in "a couple of times."

Beyond that, the gossip flew. It was the 4th of the month, just a few days after many Social Security recipients receive their payments. Maybe the killers needed money and a car to continue their spree. Maybe they wanted Clark's truck, but gave up on that idea when they saw it didn't have license plates yet. Maybe some kind of drug deal was being brokered.

Eureka police have yet to determine a motive, but don't believe Clark knew his killers, said detective Sgt. Patrick O'Neill.

Even though Clark's body was found in his truck under a pile of clothing and blankets, dead from a gunshot to the back of his head, Guyette cannot let go of the idea that the killers wanted wheels and imagined they would take Clark's.

"He always wanted a truck. He saved 1½ years for a down-payment on that truck," Guyette said. "He had it two weeks and he was killed for it."

Patrick Fealey is a writer living in Fortuna. His recent fiction will be included in "Letters to Los Angeles," upcoming from Pale House Books.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1