When I awoke one morning last month, it hit me. Oh my God, I can do this.

The next day was Saturday, Sept. 15, practically a holiday in the Humboldt Nation. Opening day of deer hunting season on the North Coast. The lightbulb moment: I would pose as a deer hunter.

While thousands of legit hunters sought only to nail another four-point rack to their garage walls, I’d be aiming to put a 30-.06 slug square into Bigfoot’s skull. A Sasquatch Soldier of Fortune, hidden in plain sight! Popping out of my pickup truck clad in Army camos, then popping the Abominable Snowman right in his furry, black dome.

This one’s for you, Grover Krantz, I vowed hungrily. It’s not that I had blood-lust or anything; I gave up deer hunting precisely because I couldn’t kill one. But Bigfoot was different. Providing the scientific community with a specimen would not only solve one of the greatest modern natural mysteries, but would also likely result in endangered species protection. Both man and Bigfoot would stand to gain. Tremendously.

After breakfast I informed my wife that I’d be gone for a couple of days, but not to worry.

I soon located my hunting license, which had been gathering dust in a nightstand drawer. It needed only to be renewed at Fish and Game, downtown. One problem: I’d long since sold my deer rifle. A new one and a box of bullets would cost a few hundred bucks, out the door. But I needed it quickly — an impulse buy. Tomorrow was going to be the big day!

An hour later I drove dejectedly home from Big 5 Sporting Goods, inwardly conceding that perhaps the 10-day firearm waiting period wasn’t such a bad thing after all.

Enter the Man-Ape

On a clear, sunny afternoon in northeastern Humboldt County 40 years ago this week, a horseback-riding Bigfooter named Roger Patterson captured on a home movie film-spool a grainy, jumpy flick that depicts a massive, hirsute, bipedal creature ambling along a creek bed.

An instantly recognizable pop culture icon, the so-called Patterson-Gimlin Film rescued Bigfoot from the Shocking!Amazing! pages of the tabloid glossies, finally confirming the source of those huge footprints Humboldt County logging crews had been seeing for 10 years. Patterson’s Bigfoot — later nicknamed “Patty” — even left six-by-14-inch footprints in the bluish-gray clay soil.

Patterson’s footage, known as “PGF” in Bigfoot circles, is regarded as the Zapruder Film of cryptozoology. ( Cryptozoology : The study of animals whose existence has not been substantiated by mainstream science.) The comparison, however, unfairly neglects PGF’s runaway popularity: While Wikipedia devotes 2,567 words to the 1963 celluloid assassination of John F. Kennedy, PGF is treated to a nearly 7,000-word analysis on the online encyclopedia.

Bob Gimlin, Patty’s only other witness, sat nearby on horseback as Patterson filmed. He reportedly had his rifle trained on Patty throughout the entire minute-long encounter, in anticipation of a hostile charge that wasn’t to happen. Instead, Patty walked calmly away from the stunned pair. (The duo had agreed ahead of time, it later came out, that should they encounter a Bigfoot, they would only open fire if either of their lives were in danger.)

Roger Patterson died of cancer in 1972. If PGF was a hoax — one that Patterson was in on — it was a secret he took to his grave. He never reaped a significant financial reward from a film that has now been viewed by countless millions around the world. His partner, Bob Gimlin, who is still alive, maintains that he was not in on any hoax, if there was one.

As PGF’s 40th anniversary approached this summer, interest on Internet message boards surged. Beer coolers and sleeping bags were exhumed from storage bins as Bigfoot geeks planned road trips to the fabled film site, now a thoroughly mapped-out Sasquatch mecca, near the town of Orleans. A symposium commemorating the legendary film was organized for Arcata, with most of today’s Bigfoot intelligentsia billed to lecture on the landmark film. (The symposium was later canceled, unfortunately.)

The hoopla, though, was justified: Since Roger Patterson unleashed his grainy clip on the crypto-world, not a single picture or video has garnered as much attention from Bigfoot skeptics or believers.

True, other “Bigfoot” have been captured on film. The reason PGF has maintained such robust crypto-longevity? Other videos fail to convince any but the most Kool-Aid drinking of Bigfooters. Even some of the more highly regarded also-rans depict nothing but pixelated, blurry Rorschachs — “blobsquatches,” as they have come to be known in the Bigfoot community. (If you doubt this, try typing the words ‘redwoods Bigfoot film’ into YouTube. Shot in 1994 by a professional film crew near the Smith River in Del Norte County, this clip is regarded as one of the top 5 or 6 Bigfoot videos ever shot. See the blobsquatch? I rest my case.)

And yet, reigning champ though PGF is, each year that goes by without a more convincing offering is one more year that mainstream science smirks at us “believers.” Trotting-out the 40-year-old home movie as proof that Bigfoot lives in the same Pacific Northwest wilderness that each year is increasingly encroached upon by more mountain bikers, backpackers and digital cameras than the previous year?

I got a “D” in statistics, but what are the odds against a brigade of huge apes hiding-out for four decades ... in California ?

Dr. Grover Krantz had a solution. Before he passed away in 2002, the Washington State University anthropologist was the modern father of legit Bigfooting. A rare academic who risked his credibility to the study, he lent a fatherly, academic tone to the analysis of Bigfoot – a field overrun with weekend monster hunters. Krantz diligently weighed the evidence, and concluded scientifically that Bigfoot was real.

But after squinting at hundreds of footprint casts and re-spooling PGF ad nauseum he, too, grew weary of endlessly pondering the sometimes sketchy body of secondary proof. Fed up with lack of a specimen, in the 1980s Krantz went public with his controversial belief: The only Bigfoot research strategy that “made sense” was to bring in a body. And because the carcass of a naturally expired Bigfoot would almost certainly never be found, any guesses what that meant?

“There will be a prize of some kind,” wrote Krantz in authoring the modern Bible of Bigfooting, Bigfoot Sasquatch: Evidence , “to the hunter who brings in the first specimen.” Keenly aware of the scorn directed his way by his Washington State University colleagues, Krantz was effectively lobbying the Bigfoot community to invest in face paint, ghillie suits, assault rifles and hollow-point bullets.

The guy wasn’t fucking around: There existed the very real possibility that Bigfoot was a relic strain of man ( Homo sapiens sapiens ), and thus protected under criminal murder statutes. But then, some level of risk is inherent in hunting a gigantic, muscular ape-man.

In the weeks preceding this article, a pining anxiety crept into my soul, and I just couldn’t shake it. Here I was, living in the heart of Bigfoot country. The popular BFRO.net Bigfoot sighting database listed more Bigfoot encounters in Humboldt County than any other county in the U.S., save for Skamania County, Wash. But I wasn’t doing a damned thing to prove Bigfoot’s existence — to dethrone PGF as the preeminent piece of evidence.

PGF had to go down. Humboldt style.

The Next Best Thing

The Brady Bill having rendered me unable to fulfill Krantz’s directive to strap a Wookiee carcass to the bed of my Toyota, I resolved to get the next best thing: A smoking-gun picture. By 2007 standards, Roger Patterson was handicapped by a funky, hand-cranked dinosaur of a movie camera. I could do better.

Logging onto eBay, I “Buy it Now”-ed a game-tracking camera with an infrared trigger. Battery powered, rain-proof and equipped with a 4.0 mega-pixel digital camera and a flash, I would deploy it in the Haunted Forest.

Constructed of heavy-duty ABS plastic and shoebox in size, my Bigfoot voyeur cam would stay wide awake 24/7, silently awaiting that magic moment when an unwitting Bigfoot tripped its infra-red beam.

Technology would be my silent assassin; the infra-red robo-cam would bring about the downfall of PGF, and put Sasquatch in Biology 101 textbooks. My crypto-geek brethren on Bigfootforums.com would soon hail me King of the Cryptodorks.

I vowed to emerge from Redwood National and State Parks in a week’s time with a digital smoking gun. The Park is a special place. Having backpacked extensively throughout Northern California’s Trinity Alps and Marble Mountains wildernesses — and, indeed, along the Bluff Creek drainage, where Patty was filmed — I can attest first-hand to the Park’s spooky, ancient mystique and treacherous “Mother Nature bats last” topography.

The perfect hiding place, in other words, for a relic population of man-like monsters.

The Haunted Forest ...

Discovered: The Haunted Forest

It’s the Fall of 2004, and I’m standing in a remote swath of ancient forest in Redwood National and State Parks. Cold fog penetrates my jeans, my sweatshirt. My hair is washcloth-damp and cold. It’s a Saturday morning.

Owing to the heavy fog, visibility is down to 50 feet. My pickup truck is parked a mile away, uphill. And despite the fact that I’ve hiked into this desolate cathedral of old growth for the explicit purpose of encountering a fabled, 800-pound, uncatalogued primate that I had good reason to believe may live here, I very much want to be back in my truck. Right now. With the doors locked and windows rolled up, heater on high and whizzing by Orick’s burl stands, on my way home to Eureka.

And yet to reach the truck — to reach safety — I first have to overcome a prickly labyrinth of sticker-brush, dangling spider webs and a graveyard of chest-high, ancient redwood logs. Not to mention the near-vomit-inducing, Blair Witch fear that permeates my shivering body.

I hear them. The nearest designated hiking trail is at least a mile away, and these woods bear absolutely no sign of human visitation. I’m perfectly alone. And yet, all around me — emanating from just beyond the radius of my visibility, just out of sight in this gloomy cloudworld — I hear them: knock, knock, knock. Always a series of three reports, and always answered by a corresponding trio of knocks, only coming from a different location, roughly surrounding me.

Someone, or something, is communicating .

Suddenly a rock lands at my feet. Then another rock whizzes by. Then another, and another.

“ What the fuck? ”

Something, lost in the fog, is running around: Branches snap, footfalls smash through the brush. I’m under attack ... but by whom? By what?

The knocking continues, and now I’m being showered with these golf-ball-sized stones. Oddly, none hit me. It soon dawns on me, though, that being struck is only a matter of when, not if. I’m not wearing a helmet or body armor. If I don’t get out of here right now I’ll soon be nursing a head wound.

But here’s the kicker: I can’t escape. My legs go cartoon-wobbly; intense nausea takes firm root in my guts. I’m on the verge of throwing up, something I haven’t done in years. (A curator with the Bigfoot Field Researchers’ Organization — a prominent online outpost for Bigfoot enthusiasts — later shares his rather fantastic theory about the paralyzing fear I’m experiencing. He says that Bigfoot are able to emit a low-frequency vibration as a defense mechanism — an inaudible “hum” that induces nausea and sudden paralysis in the same way that sound weaponry is deployed by the U.S. Army.)

You do funny things when you feel your life is in imminent danger — you make funny bargains with yourself, engage in novel survival tactics. Spaghetti-legged and watery-mouthed, I just want to be another oblivious motorist, safely behind the confines of his warm pickup. Suddenly, I’m a changed man: Bigfoot’s rock assault transforms me into the world’s preeminent Bigfoot skeptic — a Sasquatch debunker non-pareil .

“How come no one’s ever found a dead Bigfoot in the woods?” I think to myself, and am able to take a small, timid step uphill.

The rock shower continues. And my heart is audibly pulsing in my throat. But it’s working: “Anyone who believes this forest could support a breeding population of 800-pound primates is insane.”

Another step. My sea legs firm up a little more.

“There isn’t a shred of evidence that primate evolution has ever occurred on the North American continent. None. The fossil record is silent.”

I take a few more steps, but the knocks and rocks pick up.

So I sink the dagger in the heart: “The Patterson-Gimlin Film is bullshit! It’s totally a guy in a suit — and a bad one at that. Some guy even admitted to it, and a whole book was published on it.”

I’m hiking back uphill and toward my truck with an almost normal gait now, and though I’m breathing heavily and can hear rocks striking the ground, they are landing a ways behind me. The knocking continues, but it, too is gradually receding into the background fog.

“It was just woodpeckers, anyway” I argue, as my truck comes into view through the fog — but I call ‘bullshit’ almost as quickly.

I know what a woodpecker sounds like, and these were no woodpeckers.

Besides, woodpeckers don’t throw rocks. I know: I looked it up on Wikipedia.

Bigfoot Is Real

To clarify: When we Sasquatchers say that “Bigfoot is real” we’re not talking about a single beast, but rather a breeding population of several thousand individual members of an unrecognized species of primate that — but for its uncatalogued status — is a flesh-and-blood mammal in all other respects. While mainstream scientists have for the most part avoided the mystery of Bigfoot like a leper colony, the loose consensus among those academics who have ventured into the study of hairy, man-like monsters posit that Bigfoot is most likely Gigantopithecus blacki , an Ice Age holdover that crossed the Berring Strait from Asia 12,000-or-so years ago.

A monstrous primate, several of the fossilized bones of G. blacki have modernly been recovered from the Vietnamese countryside. Though the accumulated fossil record is large enough only to fill a few shoeboxes, judging by the size of its massive jaw bone, scientists have concluded that the average G. blacki specimen stood around 10 ft. tall and weighed 1,200 pounds.

So, Bigfoot was real — at least in the distant past.

Forced eastward in a search for food and temperate climes, the leading Bigfoot explanation goes, G. blacki. — like their Homo sapiens sapiens brethren — ventured over the Alaskan glaciers and Canadian tundra into what is now the mountainous Pacific Northwest region of the United States. The reclusive apes, Bigfoot lore holds, have called our forests home ever since.

Having trouble wrapping your mind around the notion that the Pacific Northwest — our extended backyard — is inhabited by thousands of Chewbaccas? I once did too.

But consider this: Since World War II, more than a hundred small aircraft have crashed in the greater Pacific Northwest. Of those, several dozen aircraft, along with their passengers and luggage, have completely disappeared, despite the best search and rescue technology available on earth. (Old guard Bigfoot hunter Peter Byrne places the number of still-missing aircraft in the Northwest at 73.) They’re gone — gobbled up by the torrential rains, thick duff, omnivorous forest critters and highly acidic soil of our Northwestern outback.

The reason no one has ever found a Sasquatch carcass out in the woods? Finding the carcass of any large mammal that has expired due to natural causes, as a rule, just doesn’t happen. Ask any forest ranger or deer hunter when was the last time they tripped over a bear skeleton.

And if you doubt that NorCal forests could produce sufficient caloric forage to support the appetites of such massive creatures as Bigfoot, don’t tell that to the Roosevelt Elk: Physically largest of all elk subspecies, the hundreds-strong herd of Roosevelts that call Orick’s Redwood National and State Parks home weigh up to 1,300 pounds.

Skeptics off-handedly dismiss the Patterson-Gimlin Film as “a guy in a suit.” But would-be debunkers have trouble explaining why technology on display in the “suit” has yet to be even approximately duplicated in the 40 years since its “invention.” Costume experts — then and now — uniformly decline attempts to duplicate its “stagecraft.” And no wonder: Visible muscle tone ripples beneath the creature’s black fur. Its hands open and close —yet, astonishingly, no human’s arms are even nearly long enough to span its massive wingspan. The creature’s motor coordination, moreover, is considered by most scientists who’ve studied the film to be vastly outside the realm of human locomotion.

Bigfoot heretics scoff that Patterson was a fast-talking confidence man who borrowed money from anyone foolish enough to fund his various Bigfoot ventures. In their deconstruction of Patterson, debunkers cite as Exhibit “A” Do Abominable Snowmen of America Really Exist?, a book he self-published in 1966, one year before he filmed Patty. A copy of the rare book is in the Eureka library’s Redwood Room, and includes a drawing of a female Bigfoot, complete with — wait for it — hair-covered Bigfoot boobs, just like Patty. Drawn by Patterson himself, the sketch is a roughly accurate portrait of Patty, right down to the gangly arms and prominent sagital crest.

And a muckraking “expose” published in 2002 purports to blow Patty right off the creek bed, claiming that Patterson mail-ordered Patty’s costume in 1967. Written by the North Carolina costume shop proprietor who supposedly sold the suit (one Philip Morris), the book “reveals” that Patty was nothing more than a young Washingtonian named Bob Heironimus, suited in the dark-brown Dynel suit that Morris sold to Roger Patterson.

But neither the costume nor anything but hearsay has ever been brought forth to substantiate that Patty was a suited human. Never mind, say the skeptics: Patterson hid his costume design “in plain sight”, unwittingly exposing it in his own book.

The number of scientists who’ve devoted serious attention to the film could fit in a phone booth, yet even they are divided on Patty’s authenticity: A 1998 analysis of the film, conducted by forensic scientist Jeff Glickman of the North American Science Institute (available online), determined that the film subject was 7’ 3.5” tall, with a chest circumference of 83.” The NASI report pegged Patty’s weight at nearly 2,000 pounds. (Other estimates range appreciably downward, in the 800-1,200 pound range.)

The late Bernard Heuvelmans (1916-2001) was well regarded as a mainstream zoologist, and keenly interested in the study of scientifically uncatalogued species. The progenitor of the field of cryptozoology, Heuvelmanns concluded that Patty was a suited human.

The Yoda of Bigfoot, in other words, was a PGF skeptic.

2007: Return to the Haunted Forest

It’s only September, but for me, the damp, drizzly air holds all the giddiness of a Christmas morning. With any luck I’ll soon be downloading pictures off the game camera that a week ago I bungie-corded to a young spruce tree in the heart of the Haunted Forest. I strapped several cheesecloth pouches of raw chicken to nearby trees, fastening the juicy bundles to trunks in view of the game camera such that, arms outstretched, the baits are positioned well above my own 6-foot, 3-inch head. (The oozing pockets of free-range, organic poultry would sit out-of-reach of every known forest inhabitant, I calculated. But a giant, bipedal ape? One could easily grab the protein-rich snacks.)

I’m hiking eagerly along toward my forest laboratory when my heart jumps: An SUV adorned with the familiar green insignia of the national park service comes to a stop abruptly in front of me. Actual visitors to the park are so rare — never mind on a chilly, late-September morning like today — that the presence of a casual day-hiker like myself is apparently an alarming anomaly.

The vehicle’s roof-mounted emergency lights flash and a concerned female Park ranger rolls down the passenger-side window, wearing a quizzical look on her face.

“Hi,” she says, but after a long pause seems unsure what happens next. Finally, remembering her script, she resumes: “And what are you up to this morning?”

“Birdwatching,” I reply, in complete semi-honesty.

I’d long ago developed the habit, while out Bigfooting, of carrying in my jeans pocket a dog-eared copy of Birds of Northern California , one I’d bought at the Booklegger in Eureka’s Old Town. Previously having had no interest in bird species other than chicken (and, once a year, turkey,) I’d since incubated ornithology into a full-blown hobby. Park rangers, you have to understand, took umbrage at the suggestion that a community of gigantic man-apes inhabited their workplace. “Bigfooting” just wasn’t the raison d’etre you offered to the authorities. Hence, the birdwatching alibi.

“Seen anything yet?” she asks.

“Nope.”

A few more seconds of painful silence, the fog drizzling audibly, and I return her unblinking gaze. These aren’t the droids you’re looking for , I mantra inwardly, anxious to open my “Christmas presents,” stored on the camera’s two-gigabyte flash memory card.

The forest ranger stares silently at me for a few more seconds, smiling uncomfortably, then wishes me good luck birdwatching.

She speeds off.

Earlier that morning, on the way into the park, as I have every morning I visit, I count the vehicles parked at Lady Bird Johnson Grove. A mere two-miles-or-so into the Park, the Grove sits near a paved, lined parking lot, and is by my estimation the Park’s most frequently visited locale. It boasts a clean restroom, after all. And the pleasantly brief, level trail that encircles the Grove provides a Cliff’s Notes version of the Park, all sword ferns and behemoth Trees of Mystery-esque redwoods.

Today, parked on the Grove lot is the same number of vehicles that I’ve noticed on my previous three trips: None.

Finally I leave pavement, and am on my way to the Haunted Forest. Immediately, I can tell something drastic has occurred: My path is littered with violently torn-down limbs and uprooted trees. Was all of this damage caused by the mild windstorm that blew through the North Coast the previous afternoon? Apparently so. Thirty-mile-an-hour gusts have rendered the path I know so well nearly unrecognizable.

I lose my bearings a couple of times, and then, there it is: My tree-mounted game camera, hanging safely right where I left it. Eager to test if it still works, I walk fifteen yards in front of it, and to my relief three quick “pops” illuminate from its flash.

All of my chicken baits, I soon see, are gone, yet their bungie cords remain 8-feet high and undisturbed.

Woo-hoo! I shout, but only the tree wreckage hears me.

I got something, Grover.

Resting my laptop on a downed redwood log and inserting the USB cable into the game cam, I witness the past week’s goings-on in the Haunted Forest.

What the ... ?

The white chicken pouches were untouched for four days: As of 3:02 p.m. on Wednesday, Sept. 26. But three hours later, they’re gone .

The only clue to what snagged them: A black-haired “shoulder,” seen, incredibly, leaving the scene at 6:07 p.m.

Something “reached” eight feet up a tree!

This absolutely screamed “opposable thumb.”

Cryptozoology Now

Look around Humboldt County: We live in Bigfoot country. PGF may be growing long in the tooth, but everything from tow trucks, parcel couriers, donut shops and a major highway (Highway 96) reiterate our heritage as Bigfoot’s neighbors.

Bigfoot lives. And yet, the flesh-and-blood creature remains tabloid fare.

Ask yourself: Would you risk strapping infra-red game cameras and pouches of chicken innards to UN-protected redwoods? I did. Charles Darwin definitely would have.

Dr. Grover Krantz said that “a few dozen specialists” would probably get funding to go into the field to gather more data when, and if, Bigfoot was finally proven real. Krantz certainly didn’t suggest Bigfooting as a viable career. Regarding other HumCo livelihoods, though, Krantz was even less sanguine.

“There might well be a major fuss about whether lumbering and certain other economic activities should stop” Krantz warned, “while the subject is investigated.”

Hear, hear, Grover. I know a Haunted Forest that needs exorcising.

My ten-day waiting period is about up.

Paper Trails

Bigfoot researcher Grover Krantz rejected as “misguided half-measures” further book research and the gathering of photographic evidence.

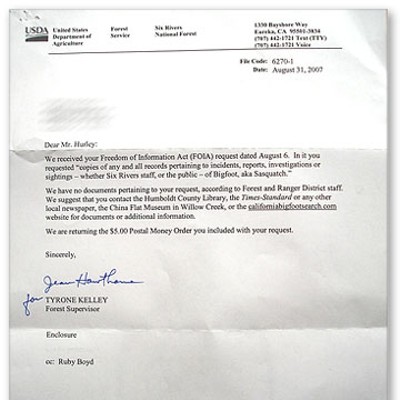

So call me “misguided” for mailing a Freedom of Information Act letter to Redwood National and State Parks staff this summer. In my request, I demanded copies of any national park records pertaining to “Bigfoot or Sasquatch.”

Enclosing a $5 money order to cover photocopying fees, I cautiously dreamed that I’d just pulled a brilliant “gotcha” on secretive park rangers: “Oh no,” park rangers would gasp on reading my demand, “some Bigfoot nut has found out about FOIA! He’s cracked the case of the missing link!”

No such luck: A week later, a responding “Dear John” letter, accompanied my uncashed money order. Park staff had no such records, the letter dryly replied.

Six Rivers National Forest also returned my $5, but offered a handful of URLs directing me to various Bigfoot websites. Yeah, like me and every other Bigfooter hadn’t already developed carpal tunnel syndrome crypto-surfing the entire frickin’ Web.

Comments