A phalanx of violet-green swallows advances slowly across the pond; each snow-bellied, arrowhead-shaped bird hovers inches above the surface and pushes, bucking, into the stiff wind. And each follows the pattern: soar, then dip and water-flick -- gotcha! Dart up, flashing a glitter-green nape and water droplets, with beakful of insect -- which wrongly had thought refuge lay in a water-warmed air pocket.

Soar, dip, flick, dart.

David Fix watches from the dirt track beside the pond. He scans the rest of the newly ponded field off the I Street entrance to the Arcata marsh. He's looking for the short-eared owl -- has seen it before out here, hunting in the tufted, lumpy landscape where the grasses, once nibbled to nubs by cows, have been allowed to stretch and diversify and house small rodents.

But though the sun heated the earth all day, beckoning spring, a cold northwest wind has kicked up on this late March afternoon. It blasts away all warmth, makes flying a chore. More birds will be lying low.

Usually Fix comes out here with a purpose. Maybe he'll look for a rare bird he's heard about, or the owls, or note the return of migrating shorebirds. But even on a mission, he takes it all in, everything: sun, grass, wind, marsh wren chatter in the rustling cattails, water ripples, redwood scent and ocean salt, the low call of the gadwall, the gull's curdle-cry -- even those yellow backhoes that have been building a new wetland out here. Ha, there's a twist, clever Tonka trucks in reverse, making habitat instead of destroying it.

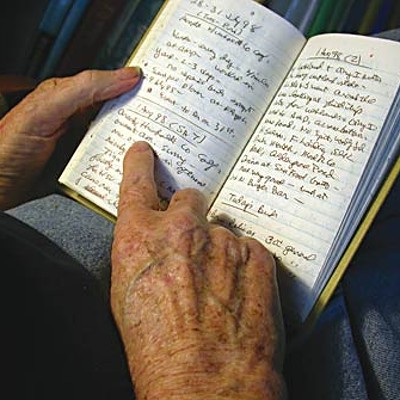

Fix drinks it all down like an elixir. He also keeps very good notes.

^^^^^

The Godwit Days festival approaches. Anyone in the vicinity of Humboldt Bay knows what that means. The faraway birders assemble their gear -- binoculars, scopes, cameras, guide books, pencils and pads, sunhat, sunscreen, hiking shoes -- and fill up their cars for the mass migration to Humboldt County. Local birders, too, adjust their schedules and get ready to step out the door.

Once gathered for the festival, the birders head, by foot and boat, to ocean and lagoon, marsh and field, alder forest and willowy creekside, beach and dune. Some, no doubt, shun the pshing crowds -- that's the sound a birder makes to attract songbirds -- and sneak off in twos and threes; after all, it is birds they're after, not noisy humans.

And then? Let the list-making begin.

Funny, that: that urge, that human drive to pry every bird out of sky and tree, wave and hillock, and demand its identification. What are you? What is your name? When did you get here and when do you leave? How many of you are here? Are you a resident? A migrant? A rare bird? A disappearing bird? A flashy vagrant not usually seen in these parts? Or just a common nobody or, worse, some insidious invader -- yeah you coot, you crow, you cowbird, you starling, fly away now and don't come back another day.

But what is this "birder"? She, or he, tromps into the countryside taking notes, checking off species on various lists -- of birds seen in the world, in a lifetime, in this county, in North America, in the backyard, in a year. Even of birds held in the hand -- that's a "kiss list." To what end, this singleminded pursuit?

Might as well ask that of Bill Gates. Or Henry Ford. Or the repetitive swallow, hunting insects, who's found a pattern that works. Or your neighborhood accountant -- especially your neighborhood accountant.

To what end? To be in the zone, that's what. To be doing what you're geared to do, to be in the game -- the "end" perhaps a mere contrivance to justify the doing.

Of course, there is also the boasting to be enjoyed: the unfurling of the list in front of fellow birders, like a he-bird fanning his outrageous plumage: Check this!

But there is an even greater end, it turns out, even if it was unintended. Scientists are taking these birders' detailed observations and using them to discern ways to, they hope, save the world.

For example, data from three ongoing surveys, conducted largely by "citizen scientists" -- our bird nuts -- have been shaped into a report by federal, state and nongovernmental researchers that notes how habitat destruction around the planet has caused some bird populations to dive. And, it suggests that a 5-degree Fahrenheit increase in January temperatures over the past 40 years has caused many birds to now winter 35 miles farther north of where they used to; some birds have shifted their wintering grounds northward by hundreds of miles. This report, "The U.S. State of the Birds," used data from the Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey, the North American Breeding Bird Survey, and the National Audubon Society's Christmas Bird Count -- an event we all know can draw the most unlikely of Johnny-come-lately birders.

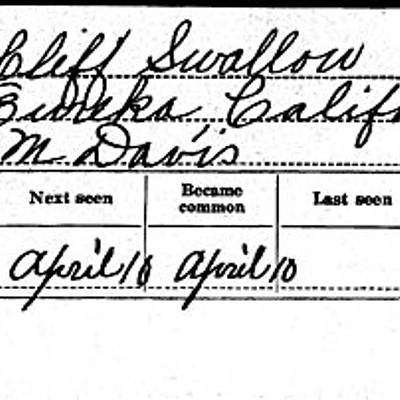

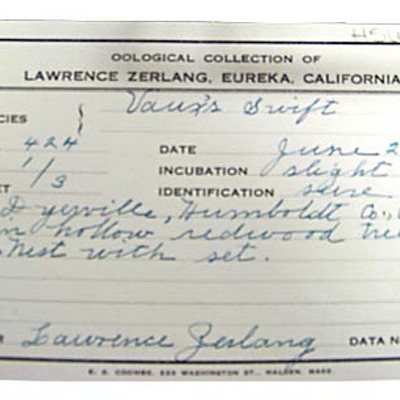

While this report relied on hobby-birder data from a 40-year span, another effort to shed light on climate change, led by the U.S. Geological Survey, plans to use data on bird migration patterns collected by thousands of volunteer observers -- some scientists, but many likely not -- between 1880 and 1970. Jessica Zelt, coordinator of the North American Bird Phenology Program at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, says the center has six million of these bird migration cards, most of which still need to be digitized and then transcribed into a computer base -- work for which the USGS is seeking a new round of citizen-scientist volunteers, by the way. Each card contains a bird species' name, the location in which it was observed, the date it arrived and the date it departed, and the observer's name. The guy who started the program back in 1880, Wells Cooke, wasn't thinking "climate change" at the time. He just wanted to learn more about bird migration. And in 1970, when a new survey -- of breeding birds -- began and the migration survey was set aside, nobody blinked. But now those old data could possibly provide a key to the future.

"I think this historic data will reveal actually a lot about how arrival and departure times of [certain bird species] have shifted over the years," said Zelt from her office in Maryland last week. Zelt, incidentally, lived in Humboldt County three years ago while doing research on spotted owls. "This is just a piece of the puzzle. The effect of climate change on migrating birds hasn't been well-documented, and we're providing data nobody else has."

Some of the cards are from Humboldt County. On one from Eureka dated Feb. 1-3, 1894, an observer named Streator noted, simply, that Cyanocitta was "Common." On another card, this time from Briceland and dated Nov. 9-20, 1905, an observer named Gaut said a bit more about Cyanocitta s. carbonacea: "The crested-jay is one of the most familiar birds about Briceland especially at the edges of timbered strips. Many were noted eating the tan bark oak acorns."

^^^^^

The marsh wrens chitter in the dried-out cattails that edge the pond. The cold wind blows. A migrant meadowlark dashes from island to field and disappears in the grass. The violet-greens, who by mid-May will be far north of here making babies in tree hollows, push ahead in their stalled but fruitful advance. And now a pair of northern shovelers furrows the water of an adjacent pond with schnozzy broad beaks. But it's someone else who goes Kree-ree. Kree-ree.

David Fix stops, plants the tripod in the bright-yellow roadside fringe of blooming wild mustard and aims the scope at a knobby-kneed character standing long-legged in the shallows, skinny beak jutting way out.

"Greater Yellow Legs," he says to a novice birder along for the walk. "Take a look. Now, do you see a sandpiper? OK. Are its legs yellow? All right! Does it have a long beak -- longer than this guy's?" He points to a picture of a Lesser Yellow Legs in a field guide -- not the regional guide he wrote, but someone else's. "Good. Now you're birding! You can be dying, in your hospital bed on a morphine drip, with Sam Waterston peering down at you from a Law & Order re-run, and you'll be able to say that you saw a Greater Yellow Legs."

Fix is a member of the Humboldt County 400 Club -- the 10 or so people who've observed 400 or more of Humboldt-occurring species. Fix explains his obsession like this: Remember that scene in the movie American Beauty of the kid showing the girl the video he shot of a plastic grocery bag floating and twirling in a breezy vortex? And the kid says sometimes he's just overcome by beauty?

"That's how I feel," says Fix. "And I think our culture tends to de-emphasize the validity of feelings. For me, birds are kind of a gateway to pleasure, because they combine form and function and color and dynamism."

^^^^^

Often, however, it all starts with a farm boy and a shotgun. That's how it was for Stan "Doc" Harris, retired professor and The Source for all things bird, locally. Harris, who is 80, taught at Humboldt State University for 33 years -- waterfowl management, wetlands ecology, advanced ornithology, museum techniques and a host of other courses. But he spent his boyhood on the plains of north-central Montana.

On a springy weekday morning in his home in Sunny Brae, Harris leans way back in an easy chair, taking the load off his arthritic spine. The walls are covered with woven baskets -- his wife, Lorie, collects them -- and paintings of birds. Every flat surface bears a lineup of duck decoys. Book shelves sag under the weight of bird books and guides -- including several copies of the three editions of Harris' Birds of Northwestern California -- and binders full of old-time birders' notes, plus dozens of notebooks containing 61 years worth of Harris' own bird observations. He holds the record for the most sightings of local species -- 440 of the 473 ever recorded in Humboldt. He has traveled the world -- up the Amazon in a dugout canoe, deep into Alaska with a crazy bush pilot, to the cloud forest to see the quetzal -- and has added to his life list, so far, around 3,400 species.

Behind Harris, beyond the bay-facing window, in the backyard where bird feeders and sunshine, shrubs and trees entice the avians, a Steller's jay goes shak-shak-shak-shak!

"I got a shotgun for my 13th birthday from my dad," says Harris. "He just turned me loose with it, and the first season I shot five pheasants and 10 ducks."

It wasn't until several years later, when he was a college undergraduate in Pullman, Wash., that he started "birdwatching." Like any kid, he knew his robins and blackbirds (although there are more kinds of blackbirds than most people realize). But one day in 1948, while helping out with some field work, he saw a Lazuli bunting. "I couldn't believe there was such a bird," he says. "I said, 'What was that?!'"

And it wasn't until 1967, says Harris, that he became a "fanatical" birder -- what his son, Michael, calls "a goner." That was when four snowy owls showed up on the north spit of Humboldt Bay, pulling in hotshot birders from the entire state with their impressive lists and lingo. It had been 50 years since the owls last invaded -- they make those rare forays out of the Arctic when their main prey, lemmings, have had a population crash. There've been a few invasions since -- Harris has an entire binder full of every local record ever made by anyone of those lovely, occasional visitors.

Hunger and beauty: Those may be the first lures birds cast at humans. Just read the journals of famous artist-adventurer John James Audubon, on whose expeditions, it seems, more ammunition was expended than in the Civil War. Open up at any page and there are guns going off and critters falling from the sky or out of trees or in their tracks. Birds, cougars, bears, deer. Quite often, a feast follows -- and, in the case of the birds, a loving reassemblage by Audubon of skin and beak and foot to create a life-like posture to sketch. From a couple of days on a Florida Keys excursion in 1832:

"[W]e beheld, right before us, a multitude of Pelicans. A discharge of artillery seldom produced more effect; the dead, the dying, and the wounded, fell from the trees upon the water, while those unscathed flew screaming through the air in terror and dismay ... .

"[Y]ou will doubtless be still more surprised when I tell you that our first fire among a crowd of the great Godwits laid prostrate sixty-five of these birds."

But Audubon and his crew ate well, and he left behind a legacy of bird lore and gorgeous illustrations. And -- along with a propensity among ladies of the time to adorn their hats with bird feathers -- Audubon's work inspired another fellow, George Bird Grinnell, to form the Audubon Society in 1886. The intent was to halt the meaningless decimation of birds for fashion. The society became a force for habitat conservation.

It wasn't just hats that brought low many a bird back then. Scientists, of course, had an interest in birds. And then there were the precursors to today's list-keepers. "It was all the rage in the late 1800s to go out and build your own collection of eggs and mounted bird specimens," says Harris. "And there was a lot of trading among the collectors."

The earliest known collector in Humboldt was Charles Fiebig, who was active before 1885, says Harris. Another was Charles Irving Clay, who collected between 1901 and 1953 -- his field notes are in the Humboldt Room at HSU, and his skins, nests, mounted birds and egg sets fill many of the cabinets and display cases in the Wildlife building. Yet another collector, John M. Davis, who was active from 1910 into the 1940s, also submitted some of those early bird migration cards in Wells Cooke's program. These and other collectors' specimens are distributed among HSU, Eureka High School, College of the Redwoods and the Clarke Museum.

"It was legal, in those days," says Harris, adding that some bird species were collected to the brink of extinction -- if not pushed over it, like the ivory billed woodpecker. "In 1918 they passed the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and it became illegal to make a private collection of birds or their parts -- even a feather -- unless they had a permit."

Some states, like California, also began requiring permits, and that shut down a lot of collectors. But some avocationists just got their "science" permits and kept on collecting -- like Humboldt cousins J. Thomas Fraser and Lawrence Zerlang, whose 5,000 eggs collected in the 1920s and 1930s are now in HSU's collection. And, in time, some eggs would indeed be useful to science.

It wasn't until the convergence of three key developments that the bloodless hobby of collecting bird identifications really took off, says Harris. In 1934, Roger Tory Peterson published the first in-depth, illustrated birding field guide small enough to fit in a pocket and geared toward the average Joe Blow; competitor guides soon followed. Then, after World War II, Americans had a bit more money and leisure time. Concurrently, over in Japan, people were looking for ways to rebuild their economy -- one result was the development of high-quality optics, and the production of inexpensive binoculars.

"That all made it possible for the average farm kid to go out and go birding," says Harris.

^^^^^

The wind blows hard. The sun drops. Still no sign of a short-eared owl. But at the north end of one of the new marsh ponds there's a band of American coots doing their jerky headbob across the water. Should be called scoots. And if you've spent any time among birders, you know that coots get zero respect. Common as dirt. Bulbous gray bodies and tiny black heads.

Fix is different.

"I'm a-religious," he says. "I don't perceive greater or lesser creatures. I tend to see there are these whole nations of beings, of species. Coots take a drubbing, but there's nothing wrong with coots. I think they're a sign of a healthy aquatic environment."

He aims his scope at an injured dunlin, its rear end messy with matted feathers. Two green-winged teals fly over the pond. Fix says, once you start watching birds you never stop learning. And they make the whole world familiar.

"Once you know what they do," he says, "you can be on the Trans-Siberian Railroad and the spruce forest suddenly opens up and you see a green-winged teal."

^^^^^

A frozen menagerie bears witness to the strange conversation that takes place one day in late March inside the main specimen collection room up at HSU's wildlife building. Ungulate heads gaze from the walls; birds in various poses gawp from every level surface.

Tamar Danufsky, the wildlife museum curator, opens up drawers and pulls out a succession of trays containing more specimens to show a visitor -- stuffed bird skins, clutches of eggs, nests. Ken Burton, president of the Redwood Region Audubon Society, hovers nearby; together, they try to explain some of the more perplexing aspects of birding society.

First of all, says Danufsky, most birders are not ornithologists. Burton adds that few ornithologists he knows go out birding.

Second of all, birders come in all degrees of intensity. Burton says he doesn't like to generalize, but he thinks that the most fanatical listers are probably men.

"And female birders tend to like to get out and enjoy socializing," he says, raising a cautious eyebrow at Danufsky.

Goodnaturedly, she responds: "I really don't like standing in a big group to see a rare bird. I think it's silly for everyone to be in one place."

Both agree that there do seem to be more male birders, overall. Which research bears out, apparently. In a Nov. 30, 2006, Discover Magazine article, writer Bruno Maddox noted, "Significantly more light has been shed on the matter by the recent work of one Simon Baron-Cohen, a professor at the University of Cambridge, who theorized that men love birding less for its resemblance to the macho practice of hunting than for its resemblance to the unglamorous practice of accounting. Men and women have different brains, he has determined. Girls are apparently wired for something known as 'empathy' ... ."

Burton confesses: "I was a list-keeper long before I was a birder. But I'm not as obsessive about it as some people."

Danufsky calls herself a reformed birder, says she likes to go birding alone these days, or with one other person. Sometimes she'll come across a group of birders and, inevitably, one of them will ask her, "Have you seen anything good?"

"I'll say, 'I've seen lots of good things,'" she says. "'but nothing interesting.' It tends to be competitive."

And those singleminded birders often ignore wondrous things happening right under their noses.

"One time, birding with a group in southwest Arizona, I saw a deer and a bobcat in a standoff," she says. "I said to everyone, 'Come here! Come here!' And they ran up, they looked -- and then they said, 'Oh. We thought you had another bird.'"

But all of that is neither here nor there when it comes to making practical use of these avocationists' data. Which is all science cares about. Danufsky pulls open a drawer and holds up a case with three white eggs in it.

"This is a brown pelican's eggs," she says. "Pelicans are on the endangered species list, and they will be coming off any day now -- they've been waiting. So, what happened to brown pelicans is what happened to bald eagles is what happened to peregrine falcons -- DDT. DDT, a synthetic pesticide, caused the egg shells to become thin and then reproduction pretty much stopped for these birds. DDT was introduced in the ’40s and was used extensively through the ’70s, and then was banned -- in this country; we still manufacture it and export it to other countries!"

Scientists know now that DDT accumulates in a bird's system, and in the environment around it as well.

"So here are these three pelican eggs, from 1927 -- pre-DDT," she says. She pulls open another drawer of egg clutches and picks up a clear case with two objects in it that look like deflated balloons. "These pelican eggs are from 1969. So, when people said, 'DDT is causing this and we need to ban DDT,' and the people who made DDT said, 'You need to prove it,' and when DDT is everywhere in the environment -- where are you going to find egg shells that haven't been exposed to DDT? In the past. So, to me, that's a really great reason for why we keep all these old things."

^^^^^

Fix turns and heads back to the other end of the pond. "Here comes a double-crested cormorant," he says.

The big, gangly dark bird with a pale breast -- a juvenile -- lands in the pond and spins around. "That's a real blue-collar bird."

Every bird has its place, Fix says -- together, they make a complete landscape. "The marsh wrens do their things in the cattail beds, while a few feet over the coots or gadwalls are executing their life histories."

And the thing is, none of them are consciously thinking, gee, this is really gonna make me a big star some day. However, some humans -- say, the competitive birdlist keepers -- might be suspected of vying for a little fame. But Fix gives even them the benefit of the doubt.

"Take Bill Gates," he says. "He didn't start out wanting to become the world's richest man. The money was the secondary product of the passion that he had. You could say the same of the listers. Most are passionately attuned to nature. You know, it's hard to go out and bird 30 weekends a year and enjoy it if you don't like nature."

^^^^^

C.J. Ralph, a biologist with the U.S. Forest Service's Redwood Sciences Lab nestled in the redwoods up behind the HSU campus, like Doc Harris is one of those rare combinations of fanatical birder and bird scientist. Ralph, who's 68, has been birding since he was 12. One day last month, he sat in his office with a green view to the outside and called up on his computer the Web site for the Avian Knowledge Network. This is the new portal, run jointly by a number of institutions, through which researchers hope all birding information will be funneled from here on out, whether it comes from scientists or hobbyists. Among the avenues into the network is the increasingly popular Web site eBird, started by the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, into which birders can directly enter their observations.

Old field notes may also be useful. Ralph lately has been talking to Harris about getting someone to help the retired professor type up his field notebooks. And those bird migration cards, from the 1880s to 1970s, could be critical to understanding climate change, says Ralph -- a phenomenon that could see a five-foot rise in sea level over the next 100 years, submerging life as we know it now. (For the record, Doc Harris doesn't think we have enough years' worth of bird data yet to tell us much about climate change.)

In fact, says Ralph, birds are the perfect vehicle for lending insight into how we might adjust to meet the coming challenges. Observing birds satisfies the human need to keep track of things, seek patterns, make order out of chaos. And, birds are more plentiful and accessible than, say, snakes or mammals.

"The neat thing about birds is, they're pretty," Ralph says. "And they come in to our feeders, so they're easy to see. They're out in the daytime, most of them. They sing and make beautiful notes. And so people are interested in them. And the reason they are good for studying our environment is, each of them is doing a different thing and all of them are out there sampling the environment. They can tell us what we're doing to it."

^^^^^

A kite hovers over a field beside the pond, then drops to a fence post. Kites -- small, snowy predators with black markings and red eyes -- thrive in Humboldt, where tree removal along the coast has created the open fields they need. If humanity were to drop dead tomorrow, says Fix, and all the trees grew back, the kite would leave to seek open country elsewhere.

Fix turns the scope back toward the pond. "There. Do you see that dull bird?" Swimming right to left across the scope's sight is a pearly gray duck-like creature with a black bill and a black butt. Subtle. But not dull -- it suddenly seems like the prettiest bird out here. "That is a gadwall." He demonstrates its slow, deep, near-comical call: "Behhk ... Behhk."

It's getting late. Fix shoulders the tripod, turns, and walks back along the dirt track toward his car. "My whole thrust," he says, "is to awaken people to birds."

Comments