On a Saturday morning early last June, Eureka High School's halls are cool and quiet. But past the heavy auditorium doors, dozens of men and women in leotards, yoga pants, sneakers and lace-up dance shoes are running through a choreography sequence, a sheen of sweat visible on a few of their faces. They kick, drop down, slap their thighs and swivel over and over.

"One, two, three, four, nasty-nasty, seven, eight," calls Tigger Bouncer Custodio as he paces upstage in a neon pink RuPaul T-shirt, his dark hair pushed back under a bandana.

Some move like trained dancers, slinking across the scuffed black floorboards. Others shuffle, hands curled as they eye their neighbors' feet. Still, everyone here has already made the first cut in auditions for North Coast Repertory Theatre's spring musical Cabaret, to be directed and choreographed by Custodio. Today they'll dance, sing and act out scenes alone and in pairs, hoping to land a part and, starting in March, rehearse 10, 15, sometimes 20 hours a week for 11 weeks, then perform 16 shows, all unpaid but for a stipend of maybe $75 that doesn't cover gas to and from the theater. Nobody is getting famous performing community theater in Humboldt County, either. But here they are, belting beside the piano at stage right and poring over pages of dialogue.

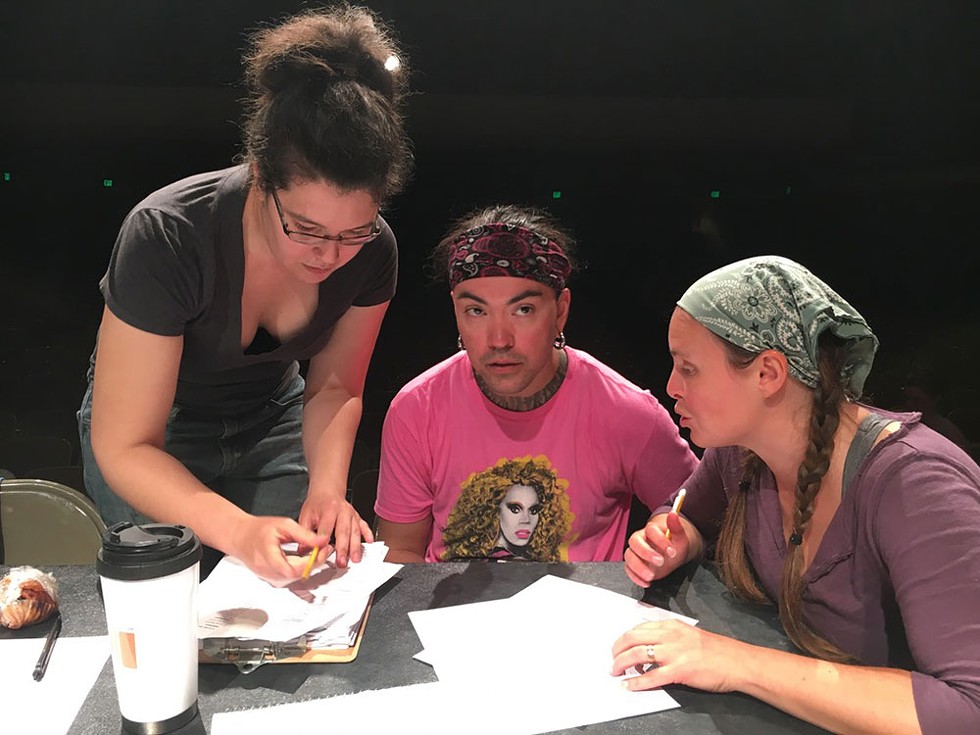

- Photo by Jennifer Fumiko Cahill

- Kelly Hughes, Tigger Bouncer Custodio and Nanette Voss deliberate over casting.

Musical director Nanette Voss explains that dance-heavy shows often hold callbacks but the rigor is unusual. "Tigger is pushing them ... we want to see their stamina," she says. Girlish braids hang below the bandana tied over Voss' head, belying the exactitude of her role here and as an English and drama teacher at EHS, where she's also director of the theater program. She's been doing theater since she was 10 and later began professional training. "Then I realized I'd rather do this for fun," she says. Voss plays a verse of "Cabaret" on the piano for four women whose hair is still damp with sweat, watching them intently.

Kelly Hughes, assistant director for the show, huddles around a folding table with Voss and Custodio during a break to go over the relative merits of the 40 performers on the list — whose vocals are "all over the place," who dances with "charm" and who's giving them goosebumps. Two days later, they post the 19 parts and wait to hear who accepts and who's going with another show.

On March 4, just less than 11 weeks from opening night, a dozen members of the cast are back at the EHS auditorium, scattered in the first few rows of the house. Custodio tells them he wants everyone "off book" — with songs and dialogue memorized — in two weeks.

There's still a call out for actors of color, he says, "because that's part of the story we're telling." A few minutes later, Claire Fuxabull (her VaVa Voom Vixens burlesque name), a tall African American dancer with a bob of loose curls, walks in and assures Custodio she can pick up choreography quickly. Custodio sits back in his velvet seat and sighs, "God is on my side."

Based on Christopher Isherwood's 1939 novella Goodbye to Berlin, the musical adaptation Cabaret centers around a seedy nightclub in 1930s Berlin, where the Nazis are rising to power. The characters are increasingly swept up in the terrors of fascism, despite the varying depths of their denial. The connections to the current moment are hard to miss, given the resurgence of Nazis and their white supremacist brethren in the U.S. and abroad. By bringing people of color and more LGBTQ performers into the Kit Kat Club, Custodio, who is a Filipino Indigenous American gay cis man, is hoping to expand the idea of the vulnerable — then and now. Likewise, the Nazis are updated, sporting white polo shirts and khakis like their contemporary counterparts.

In this production, some of the furniture is portrayed by people, too — frozen in place as lamps, doors and coat racks. Little by little, it goes from shocking to expected, played for laughs, then cruel. Finally, Custodio says, it ends in "complete objectification. Complete loss of humanity. ... Because that's what happens. ... It's how people of color are looked at. How queer people are looked at."

Of all the emotional aspects of the show, the last degradation is the most taxing for Fuxabull. "Being a footstool is the hardest part for me. Because I am not," she says, hand raised, "a footstool."

Craig Benson, who plays Herr Schultz the fruit seller, says he was drawn to the show partly because he knew Custodio would have "a take that was courageous, definitive and political." He leans into the lobby table, his eyes, one blue and one green, unblinking. "I'm Jewish," he says. "It tells the story of Kristallnacht. I'm playing Schultz, a man who's in denial." Aside from the emboldened anti-Semitism, Benson sees parallels with denial about climate change and attacks on the rights of LGBTQ people.

Cabaret will be Benson's third show with NCRT, though he's directed five shows and acted in somewhere around 10 other Humboldt productions. By day, he teaches environmental science and management at Humboldt State University. "My head is in the sciences all the time and I need something for the other side of my brain," he says gesturing toward his gray hair. And while he finds creativity in his field, "I don't get to move like this. I don't sing. ... It's mind, body, spirit and community." Most of his colleagues don't know about his other life. "I'm not outed as an artist," he says with a smile.

- Photo by Mark McKenna

- Calder Johnson and Tigger Bouncer Custodio watch rehearsal a week before opening.

On March 28, seven weeks out from opening night, the small mirrored studio at CalCourts Health and Fitness on Broadway in Eureka is crowded with dancers running through the choreography for "Don't Tell Mama." Noel August, who performs in drag as Tucker Noir, stands in the corner, a beanie tipped back on her head, watching them spin and drift into line with varying degrees of smoothness, sneakers squeaking above the music. She's here to "tighten up" the choreography. "It's like hearing it from another parent," she says.

When the music stops, the dancers drop their saucy postures, blow the hair off their faces and listen to August's notes. They're to watch finger positions and other details that will "cue the audience that this is a tight number." She demonstrates how they can achieve "sharpness" by engaging every muscle as though they're moving against something more than empty air. They go again, this time with Custodio shadowing them, his double claps cracking through the room.

- Photo by Mark McKenna

- Ten-year-old Lily Herlihy helps Maggie Hockaday with her makeup.

A couple weeks later on April 15, half the cast is scattered around the stage under the fluorescent lights of the Jefferson Community Center. Once the set is more or less built, they'll move to NCRT. Jenni Simpson, who plays the prostitute Fräulein Kost, holds a script tabbed with pink Post-its.

Simpson is used to performing with Jenni and David and the Sweet Soul Band but, she says, pressing the red curls back from her forehead, "Acting is not something I do." Voss encouraged her to try out for the show and Simpson, who works as a project analyst for the environmental consulting firm GHD, saw it as a chance to stretch creatively. "It's interesting to have a really full life and to have this absorb everything," including some of the time she'd typically devote to her band and her dog.

"I like [Kost]," Simpson says. "Ballsy isn't the right word but she's kind of a badass." It makes Kost's betrayal, aligning herself with the Nazis, more painful to portray. "Her choice is out of her own heartbreak and despair," she says. "After I sing 'Tomorrow Belongs to Me,' we come back and have a circle and I'm really grateful."

Tonight they're going through the scene leading up to the song "Somebody Wonderful," a duet with Benson and Dianne Zuleger as Schultz and Schneider, who are newly engaged, with a wistful Kost singing in German in the background. Simpson is tentative in Kost's telling off her landlady but soon she leans into it, sneering.

"Yesss!" roars Custodio, cackling. "Give it to her!"

- Photo by Mark McKenna

- Members of the orchestra.

Once the song begins, the scripts they've been sneaking glances at fall away and Benson and Zuleger lock eyes, their voices filling the room, which suddenly feels like a theater. Then Simpson, who doesn't speak German, picks up the melody, singing the words with Kost's lonely cynicism and a splinter of hope in her broad alto. When the song ends, she huffs a breath and a couple of castmates swipe at tears.

Custodio asks Simpson how she's doing during the break, telling her to let him know if anything becomes too much. There will be rough and gritty scenes in the show, depicting prostitution, violence and humiliation that could be difficult or triggering. "I'm not interested in capitalizing on anyone's trauma," he says. His own training at the Webster University Conservatory of Theatre Arts was in method acting, drawing upon one's own personal experiences and pain to bring "emotional rawness" to a performance. The result, he says, was "really powerful. But was it worth it?"

The word "consent" comes up frequently in rehearsals and the players check in with each other about scenes with any contact — and there's plenty of slapping, grinding and crotch grabbing. This is Custodio's first time directing community theater, though he has four years directing kids at Fuente Nueva Charter School. He's performed in Les Miserables, Rent and Chicago in Humboldt, as well as choreographing Pippin. "I know I have the ability to do what's in my head. I do it on stage, I do it as Mantrikka [Ho]," he says, referring to his drag persona. But "to direct others and see a different interpretation is another level."

He stops to make a note in his battered spiral notebook to remind Hughes it's time for them to "get real about consent" and what's coming emotionally in the second act.

- Photo by Mark McKenna

- Tyler Elwell glams up to become a Kit Kat Club boy.

On May 1, two weeks away from opening night, the cast is rehearsing on the NCRT stage, where the bones of the Kit Kat Club set are built and awaiting paint. The smell of sawdust is sharp.

The players move through their warm-up exercises in a mix of workout clothes, skimpy costumes and heels that require some getting used to, particularly for the men who've never worn them. Tonight they'll run through the second act accompanied by piano under the hard, white lights. Emma Johnstone sings Sally Bowles' iconic anthem "Cabaret" for an audience of a dozen castmates.

"Where are my Nazis?" shouts Custodio, summoning a handful of actors to loom menacingly in the wings. Choreographer Caroline McFarland runs them through the fight scene, which is still stiff.

Once they've made it through to the grim finale, the cast takes seats in the house to hear notes on their singing, dancing, posture, acting and accents. Calder Johnson, the theater's creative director, addresses the troops, too.

"Well, that got dark, didn't it?" Johnson's is an actor's voice and it carries to the rafters. The darkness, he tells them, is necessary to this "story from 100 years ago about people trying to get all the joy they can out of life as the world falls into fascism and darkness." He jokes that it's not relatable at all before continuing. "We have to commit to that 100 percent and because of that we have to take care of ourselves as actors and as a family. We have to be able to step out of it." He also reminds them to project their voices from their diaphragms and thanks them for the hard work that's taken them this far. Now, he says, "You're hoping for that moment when the plane lifts off before you run out of runway, which is opening night."

Johnson started at NCRT as an actor in a production of Cabaret 15 years ago, working with the theater off and on before becoming managing artistic director three years ago. "In some ways," he says, Humboldt County is "an anomaly because so many people value the arts. ... People love to have these visceral experiences that you can't get from Netflix on your couch." That a largely rural county like Humboldt fills seats not only at NCRT but Redwood Curtain Theatre, Ferndale Repertory Theatre, the Arcata Playhouse, Dell'Arte International, HSU productions and Redwood Playhouse in Garberville is remarkable. According to his estimates, the theater is able to survive financially on 75 to 80 percent earned income from ticket and other sales, in contrast to the national average of 60 percent, with the other 40 percent coming from grants and individual donations. Even so, there isn't enough cash to pay the actors like professionals without boosting ticket prices to $40 or $50.

Mounting a production is made significantly easier by the fact that NCRT owns its building, but it still adds up to between $9,000 and $12,000. Just renting the rights to perform a show runs $4,000 to $5,000. Another $1,500 to $2,000 goes to costumes and scenery, $2,000 to $3,000 goes to the musicians, stage manager and costume and set designers. That leaves $800 to $1,200 to split among the cast. Johnson points out that some of the actors donate the small amount of cash back to the theater. "It's a tremendous amount of hard work," Johnson says, basically for free. "It's unlike any other hobby."

- Photo by Mark McKenna

- Gary Bowman plays cello as the Emcee.

There's one week left for rehearsal, all under "show conditions," meaning makeup and costumes, lights and orchestra. On May 8, the band is upstairs in their own mishmash of black, gauzy, skin-flashing costumes. They've had a month of weekly practice and two weeks of intensive rehearsals late into the night with the cast.

Backstage is a rabbit warren of small rooms littered with the detritus of construction and costuming. The dressing room is a narrow space flanked by lit mirrors, the vanity shelves below them covered with an explosion of makeup palettes and train cases, abandoned eyeglasses and water bottles. Down the center of the room a clothes rack is packed with vintage coats, dresses and lingerie marked with the name of an actor and the corresponding character. By the end of the night, everything will be everywhere.

Gary Bowman, who plays the Emcee, arrives early to tune the cello he'll play on stage and practice his choreography. Luckily it's a quick commute from his job as an eligibility worker in the CalWorks division, helping people get food, cash and healthcare assistance. He sits at the mirror with his eyes closed as Karen Echegaray, who plays a trans sailor, fixes his makeup. Soon he'll have a glittery black stripe painted down the center of his smooth head. Bowman toured with the Broadway revival of Cabaret in '99 as a cellist in the orchestra and understudy for the part of Ernst, and he'd played the Emcee back in junior college. Still, he was "shocked and a little intimidated" to land the part at NCRT.

Like some of the folks Bowman works with at his day job, "The Emcee is a person on the fringe also." He adds, "Half the reason I do theater is to keep you sane from your day job. It's very cathartic."

Stage manager Kira Gallaway has added a bulky headset to her uniform of black leggings and tank top, her blonde hair pulled back in a ponytail dyed pale lavender at the end. She's zipping between the crowded dressing room and the house. She may, in the midst of talking, put one finger up and pivot away, talking to someone on her headset

"I've always liked being behind the scenes more," Gallaway says. Her day jobs are more of the same, as a "black shirt" stage manager for Center Arts and technical director for the Arcata Arts Institute's theater. She likes being in charge and fixing problems, she says, as well as "watching the process, watching the actors just blossoming ... and all the technical aspects coming together. It just gives me such joy." Her family isn't into theater, she says, and she doesn't expect them at the show. Which is fine. It's fine not being out there for the curtain call or applause, too. "I don't need the glory. I just need what gives me that joy."

The cast warms up with yoga in heeled boots and bustiers. Then they run through the show from start to finish, with Custodio occasionally calling "Hold!" to make adjustments. Bowman flubs a line and hops, muttering "fuck" for a second before he's back in character. "Don't Tell Mama" is tight enough for the dancers to add playful winks.

When it's over, Voss gives her notes first. "Feel the music," she tells them, and "pull into the band" to keep up. Everything still needs to go faster. She wants Johnstone to "really push the song out of your heart."

Custodio flips through his notebook and speaks in the clear rapid fire manner Hughes says "engenders loyalty" and confidence. It also leaves little room for disagreement. "This is a non-nipple Cabaret," he says, dead serious. "If you have nipples and they have the possibility of showing, you need to put pasties on them." Also, "Everybody needs to be louder."

- Jennifer Fumiko Cahill

- Craig Benson as Herr Schultz and Dianne Zuleger as Fräulein Schneider.

Preview night is always a Thursday and lightly attended, mostly by other theater folks, but it's the first time the cast will get the real-time feedback of seeing an audience's faces and hearing the laughs, applause and silences. "It's the last ingredient they need," says Johnson.

At 6:55, much of the cast is on stage, still in street clothes. Voss calls down from the orchestra above with some quick notes: "Practice makes permanent," she reminds them, and hold the note longer at the end of "Willkommen."

Custodio arrives in a black button-down shirt and pink bowtie. After his job at Dirty Business Soil Analytics, he taught a Zumba Class at CalCourts before running to the theater. Rehearsals went until midnight the day before, which, he explains, is why this is called "hell week." He shares the feedback he got from a couple of folks he'd invited last night. "I got, 'Was it your intention to have people counting the choreography?' Of course, I said, 'Yes.'" He tells the cast to trust and enjoy themselves, to make the audience "want to "jump on stage and join you."

After one more run through the fight choreography, the cast retreats to the dressing room and the house fills to about a quarter capacity. Gallaway snakes through the dressing room reminding everyone to whisper. A few people are smoking out back under umbrellas and someone needs a shoe glued. Custodio is moving between actors, giving them last-minute notes and words of encouragement. Bowman's knee is bothering him, which he says is "kinda par for the course."

"This is my most nerve-wracking night," Custodio says, hunkered in the back row. He wants the audience to be engaged, to get "the general gender fuckery of it all." He'd been taught you only get two scenes to draw in the audience.

"Mein herr und herren, ladies and gentlemen and everyone beyond the binary," calls Bowman under the pink lights, kicking off the ribald "Willkommen." The audience hoots and whistles. The mood shifts when the Nazis show up before intermission. It's jarring and the audience members blink at one another in silence when the lights come on. It's the shock Custodio had hoped for instead of applause.

Backstage someone whispers, "They're feeling it."

After the grim finale and curtain call, the cast members wade into the audience to greet friends and the theater becomes an impromptu party. Voss has only one page of notes, rather than her usual three or four. Hughes has a couple of technical issues to fix. Most take off their makeup, change and head to Ernie's bar for drinks and a smoke on the patio, where, Custodio informs with an arched brow, "Everything is off the record."

Friday's opening night is already sold out. Custodio feels good, though he has a couple of tweaks. He's sure that no matter how strong the show is, it won't "get a standing O," since the harsh ending is difficult to clap for.

But opening night receives a standing ovation after all. In a message, Custodio is pleased but still unwilling to declare victory. "Can't really judge that until Sunday."

Jennifer Fumiko Cahill is the Journal's arts and features editor. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 320, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @JFumikoCahill.

Comments