The V-formations of honking Aleutian Cackling Geese that decorate our skies pose the question as to whether they fly in formation for social cohesion or to conserve energy. The reason military jets fly in V-formation is not to conserve energy, but to permit trailing pilots to remain in visual contact with the leading pilot. Fortunately, there are methods by which the question of energy conservation can be investigated. If trailing birds benefit from air currents produced by leading birds, then their relative positions should optimize those effects.

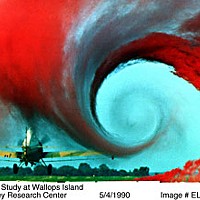

One might expect that a bird following very closely, with beak on tail, would experience less drag. Cyclists employ that "drafting" technique on the race track. However, air immediately behind a leading bird is sinking, so drafting is not a good tactic in flight.

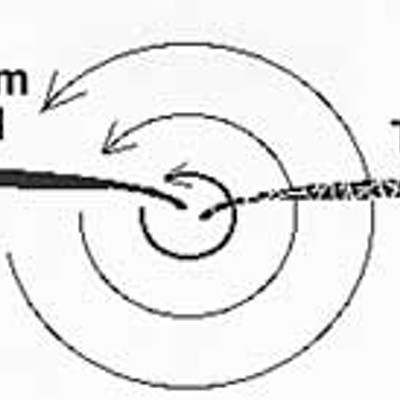

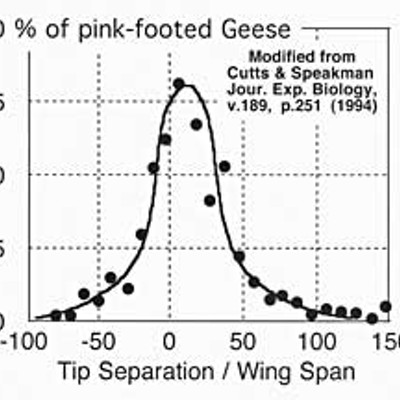

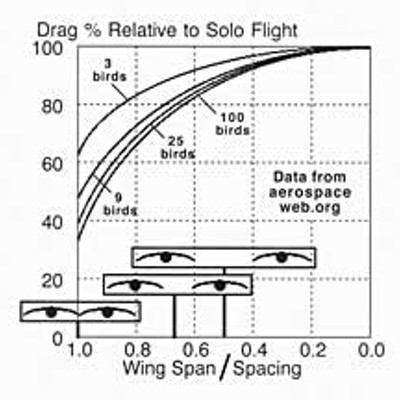

Theoretical calculations indicate that a bird in a large formation could reduce "induced air drag" by 60 percent by riding the rising half of the wing-tip vortex produced by the bird ahead. The optimum effect occurs when wing tip directly follows wing tip with zero lateral spacing. Examination of vertically-taken photos of pink-footed geese confirm that those geese fly close to that optimal geometry.

The telemetered heart rate of a pelican has been found to be faster while flying solo than in formation (Nature, Oct. 18, 2001). This further confirms the energy-saving hypothesis. And a heavy goose flying non-stop from Humboldt to Alaska needs to be as energy-efficient as possible. That is why our sky is festooned with geese in formation.

Thirty years ago there existed fewer than 800 Aleutian Geese. Thanks to the removal of introduced foxes from critical nesting islands, their population now exceeds 100,000. That's too many, according to local dairymen who see their pastures flying away.

Comments