Figuring out what Reuben Sorensen's paintings mean is almost as hard as figuring out how to get to his house.

I'm counting the number of bridges I've driven over since I turned off the asphalt road that leads west from Redway through Briceland. My compact Japanese car is way out of its element. It's raining and the washboard dirt roads are slick. With every hairpin turn, I worry I'll end up stuck in a deep rut washed out by last night's storm. So far, so good.

I've driven miles into the forest already and I haven't passed another car yet. I glance down at the gas gauge. Three quarters full. That's good. I wonder, though, if the car's tires can handle all the rocks.

I pass an abandoned school bus riddled with bullet holes. The few houses I've passed so far seemed uninhabited too. There was a moss-covered tricycle a while back. If I disappeared out here, no one would come looking for me until well into next week. What have I gotten myself into? I wonder aloud. And all for the sake of ... art?

Then finally, after miles of snail-paced, tedious driving deeper into these sylvan boondocks, a handful of nameless bridges, a power box, where I turned left at the fork, and a large silver water tank, I find what I'm looking for. A green, hand-painted sign hanging from a tree trunk announces, "Freeway Entrance."

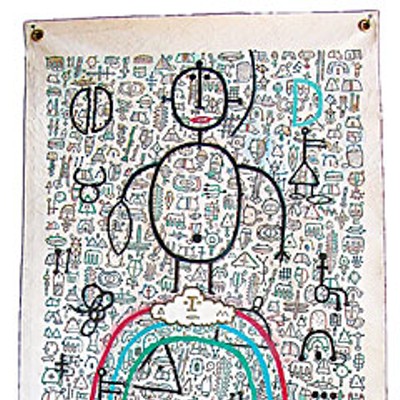

Cars, headless basketball players,caged gorillas, children's alphabet blocks and hieroglyphs are just some of the elements that make up Reuben Sorensen's strange vision of the world.

Sorensen's asceticism and remoteness are what first piqued my interest in him. A couple of months ago I read about a reclusive self-taught artist making paintings, the likes of which I'd never seen before, in the backwoods of southern Humboldt County, and I wanted to know if he was really the outsider artist others claimed he was.

Pulling my car off to the side of the dirt road just in front of the surreal "Freeway Entrance" sign, I stepped out and stretched my limbs. The forest was eerily silent. Then a gruff voice startled me from the trees below.

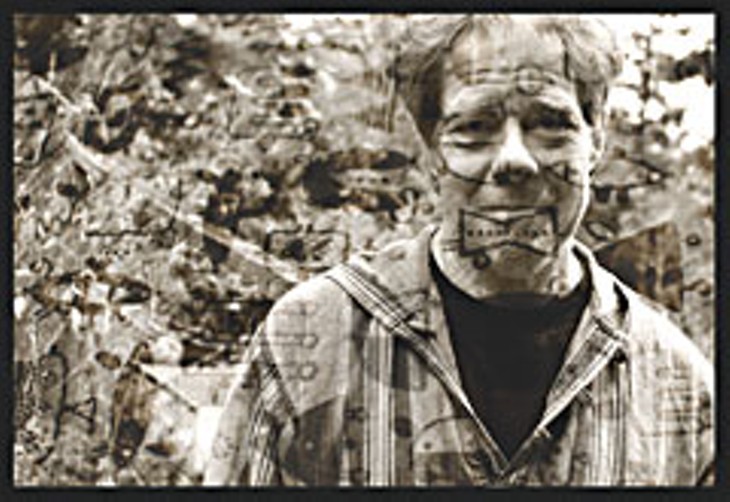

Sorenson, a compact man who walks with a cane because he suffers from arthritis in his hips, hobbled toward me up the steep, muddy path that connects his wooden shack to the main road. When he came closer, I noticed that the 61-year-old painter has the same chewed-up and spit-out look as Tom Waits. He gave me a suspicious once-over. Understandable. Sorensen doesn't get a lot of visitors out here. Then, leading me back down the path, he told me to watch my step as he maneuvered over the rough ground like a mountain goat, aided by his cane.

The entrance to Sorensen's studio is a heavy wooden door, what you'd expect to heave open before going into a dilapidated barn. But it has a very Sorensenian touch — its surface is cluttered with a bric-a-brac of magazine clippings and postcards. There are religious icons, sketches, Chinese characters, pieces of sheet music. It was my first glimpse into the physical surroundings that shape Sorensen's inner world.

When we sat down, Sorensen quickly dispelled the notion I had entertained for the past couple of weeks of him being an "outsider" artist. Even though his often child-like creations are marvelously uninfluenced by other schools of contemporary painting, Sorensen doesn't want to be associated with Outsider Art.

That's a "diluted term," he told me, slightly disgusted. Sorensen speaks slowly, mulling his thoughts thoroughly before forming them into laconic phrases. "I'm more of an outsider in life than in art," he explained from his rocking chair, an old beaten up thing covered in a Native American blanket, which is one of the few furnishings he has in his shoebox home.

Sorensen calls his art "visionary." Gesturing towards a large painting, a bird's eye view of four rotund baseball players standing around a disproportionately small baseball diamond, he said that it was "... something that I did because it needed to be expressed — it was a vision that I had."

Considering the process further, he added: "You can't just have a vision. It more or less just has you."

In 1990, Sorensen was had. He saw a vision of a car and promptly sculpted it in papier maché. It sat around for about 10 years and then he got the idea of making more cars — trucks, sedans, station wagons, whatever — until he had about 500 hundred of them. In 2005, the cars were on exhibit at Oregon State University in Bend.

The un-plastered walls of Sorensen's home are thin, but a wood stove keeps it toasty inside. The dimensions of his hovel are a few paces by a few paces. He has no plumbing — only an outhouse, up a ways from the house. When we first sat down to talk, water was heating up in a kettle on a camp stove — the kitchen. I sat on Sorensen's only other chair, which is splattered with dried acrylic paint.

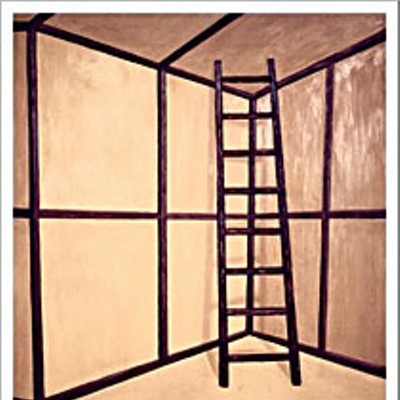

Sorensen mostly paints in acrylic, but also uses pen and marker. Still, he's open to just about anything. He pointed out three smaller canvases hanging on the wall he had yellowed using spent tea bags. A few examples of his cars were lined up on the floor beside me. There was a tattered couch as well, and a solid table with drawers onto which Sorensen rolled out his scrolls — long canvases covered in hieroglyphs — later that afternoon. In the back of the room is a crude ladder that leads up to a loft-space where his bed is. The image of a ladder crops up repeatedly in Sorensen's paintings.

This is rough living, but Sorensen isn't complaining.

Holed up in his crude studio home in the middle of nowhere, with neither car (he's never driven in his life) nor phone to connect him to the outside world, Sorensen seems, incongruously, to be lacking nothing: He has books, a computer with high-speed Internet access via satellite link (an ironic twist on the traditional hermit lifestyle), rolling papers and pot, and, occupying every square inch of his walls, artwork.

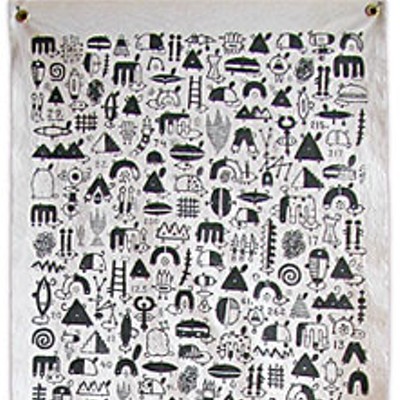

Behind him, on a tall piece of corrugated sheet metal nailed to the wall, he's painted black hieroglyphs, a code that appears in much of his other work. On the outside of the house, painted in white on black tar paper, are stick-figure drawings of what Sorensen says could be turkeys, but they might also be dogs or sheep.

When it comes to interpreting his art, Sorensen gets even more quiet than usual. "It's a mystery to me," he said.

It's hardto put one's finger on what is and isn't Outsider Art.

According to Raw Vision magazine, a publication devoted to the subject, Outsider Art includes the kinds of "creative expression that exist outside accepted cultural norms, or the realm of ‘fine art.'" Granted, that description could be applied to a lot of contemporary art, but what sets Outsider Art apart is that its "creators would not consider themselves artists, nor would they even feel that they were producing art at all."

That's why Outsider Art has historically been produced by patients in mental hospitals who weren't concerned with how to secure their first solo show.

From my interactions with Sorensen, it was clear that he wasn't crazy — at least not any crazier than your average 60-year-old who lives off the grid in Northern California. But he did seem driven by something more authentic than a desire to be famous. According to Raw Vision, outsider artists "create their works for their own use, as a kind of private theatre," which is an apt description of the rare glimpse I'd gotten of Sorensen's private world in the forest.

But it's not that simple, says Cleo Wilson, executive director of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago. "Generally, outsider artists are unaware that what they are creating is art," she wrote in a recent e-mail. "It is often done in secret and compulsively created without an audience in mind." As for Sorensen: He is "self-taught and may be a visionary," she said, "but all self-taughts are not outsiders."

Sorensen didn't seem overly concerned with reaching out to his audience when we first met; getting him to explain what his images mean and what his artistic process entails was like pulling teeth. When asked why his basketball players were headless, he responded: "It's another one of those things."

However Sorensen's reticence alone doesn't make him an outsider artist. He is, after all, not oblivious to the fact that he is making art, nor that he has an audience.

"My whole intention is to give other people energy," he said, opening up. "I'm not trying to tell them a story. You can do what you want with the energy."

Sorensen has shown his work in southern Humboldt, Bend and Kansas City, Missouri — and his paintings are very much for sale, some with price tags of upwards of a thousand dollars.

In 2006, he was featured on Rare Visions and Roadside Revelations, a show produced by Kansas City Public Television. The goal of the Rare Visions project, according to its website, is to document one of the "least documented and fastest growing areas in the art world." Visionary Art, Outsider Art, grassroots or self-taught art — the show's producers can't seem to decide on one term so they use them all interchangeably.

Sorensen's paintings can also be found at Detourart.com, which lists hundreds of American outsider artists. However, Detour Art doesn't do a good job of defining Outsider Art: "We are crazy about this stuff called Outsider Art, Visionary Art, Art Brut, Folk Art or whatever you want to name it ... it is a pure root art form, like a visual blues or jazz."

Carol Es is an L.A.-based painter, bookmaker and illustrator. She co-founded the now-defunct alternative online magazine Picklebird, which published a feature on Sorensen about five years ago. And she's a fan.

"Reuben is an outsider in the sense that he is definitely working outside of the mainstream, and is undoubtedly influenced mainly by a very unique inner visionary instinct that is personal," she explained in a recent e-mail.

But the term comes with a lot of unwanted baggage. "Some folks get a narrower view of the outsider," Es said, "picturing someone who is entirely cut off from society, or even mentally challenged." That's why she tries to "stay clear of it, or make qualifications ... I too am self-taught, and have no formal education, but like Reuben, this does not mean we aren't educated."

"When I first saw his work, it was a ‘Bingo!' moment. Reuben is a great artist on all levels. He is not half-assing anything. He LIVES it," she said.

Sorensen grew up in a suburb outside of Milwaukee, Wisc., the son of an accountant and a schoolteacher. He remembers making pencil drawings as a child, sitting beside his father, at his father's desk — a possible explanation for why he includes numbers in his adult paintings.

When Sorensen was three or four, he started drawing cowboys and Indians with pencils and crayons. Even then, he said, his figures were headless.

But Sorensen's parents never encouraged his art. In fact, they "vehemently discouraged it," he said. "My mother had strong intentions about my being a ‘success.' This was the '50s, and following art was not likely to make one into the image of the middle-class businessman with the three-piece suit and two cars in a garage."

Perhaps in reaction to this, Sorensen said that when he was seven he took his art "underground." He started to destroy nearly all of his drawings — "tearing them up into little tiny pieces and burying them at the bottom of the garbage so that even if someone discovered them they couldn't see what they were of, or about."

By the time he was in the second grade, Sorensen had already plotted his rebellion. His mother pushed him to excel at school. His teachers at the time said he was a talented artist, but his parents would hear nothing of it. So according to Sorensen, little by little, he started acting dumb to convince his parents that academia wasn't the right path for him. "Year by year, I worked my way down from the top of the class."

By the time Sorensen was in his late teens, he had rejected the middle-class values of his family and community and "chosen a life on the streets." When he was 18 he became a hobo, riding trains between Wisconsin and California. That lasted for about a decade before he eventually settled in Humboldt County in the '70s. He just got tired of traveling and needed "some place that was quiet," he said.

In the meantime, Sorensen never stopped painting, but the work he showed me in November — what he described as "mining the unconscious" — is stuff that he's produced over the last 10 or so years.

When I asked Sorensen what he was reading these days, he took a dog-eared copy of Carl Jung's The Undiscovered Self from the shelf. It's something he comes back to again and again, he said.

Jung, a Swiss-born psychoanalyst and contemporary of Sigmund Freud, was the founder of analytical psychology, a clinical approach to understanding the inner-workings of the human psyche that draws on the symbolism found in dreams and in other creative processes, as well as Jung's own home-grown theories on archetypes, complexes and the collective unconscious. Throughout his career, Jung was also deeply interested in such diverse fields as alchemy, Eastern religions, astrology and mythology.

Sorensen, like Jung, is a vagabond of the unconscious mind. But the painter told me he's not capable of explaining the psychology behind his own work. To learn more about the role psychology plays in his ouvre, he suggested I contact a fellow artist he met on the Web.

Enter Carol Spicuzza, a self-consciously Jungian painter based in Indiana who has shown her visionary paintings all over the United States and in Europe. Spicuzza's visions are the kind you imagine seeing in a near-death experience. They have an ethereal feel to them and often include astronomical images: a moon reflected in water, shooting stars and luminescent orbs.

In an e-mail correspondence, Spicuzza said that Jung's concept of "individuation" is very important in Sorensen's work. Individuation, according to her, "involves integration of the unknown aspects of oneself and a turning away from mass culture." Jung, she said, was also very concerned with the "effect of modern culture on the natural man, on man's animal nature." And Sorensen's work, she continued, is an exploration of just that effect:

In his early work we are faced with the constricting nature of modern life. One senses a great dissatisfaction with and recognition of a certain meagerness in our lives. Reuben illustrates our feeling of being caged by modernity and hints at a desire to get at an authentic and essential aspect of life that has slipped out of our reach ... Freud said that visual thinking is a more unconscious process than verbal thinking, the former being older than the latter. One can see vestiges of our older visual language in ancient rock art with its many simple, symbolic shapes. In works like "Reverse Destiny" and "Butterfly Tree," it is as if Reuben is referring back to our ancient visual language and creating an updated version that might serve to convey our unexpressed feelings about life in the machine age. Can our animal nature be welcomed in this technological world? I would like to think that artists like Reuben are trying to open the door.

In a 2003 children's book, The Laddernest,written and illustrated by Sorensen, the artist/author takes the reader on a psychological journey of discovery that starts with a family outing and ends with an escape. The final escape is facilitated by a ladder that leads up and out of a place called "HOME," which, Sorensen writes, "looks like some kind of unstable storage space for sad memory." The story employs many of Sorensen's staple images: children's alphabet blocks, a caged gorilla and a headless cowboy.

The Laddernest is a children's version of a Bildungsroman. It plots the development of the unnamed protagonist from childhood through maturity. In that process, he discovers what it means to be an artist and a man. Invoking Jung, Spicuzza calls the book "a playful and witty description of the individuation process."

One after the other,Sorensen unrolled his scrolls out on the table for me.

"Butterfly Tree," one of the paintings Carol Spicuzza mentioned, is a sterling example of what Sorensen has done with his original visual lexicon. The weird collection of images that make up this 7-foot long scroll appear to be half-mechanical, half-biological. There are controlled squiggles, ladders, numbers, things that look like coffee beans, others that — to me at least — resemble genitalia, and still others that look like strange animals and instruments.

For the most part, Sorensen's hieroglyphs resemble the world we're familiar with only tangentially. They hold the viewer at the edge of understanding, but never let him go any farther. They are both playful and disturbing. Packed, they beg to be unpacked, but they admit, somehow, that decoding them is probably impossible.

"You can't connect the dots," Sorensen said. "It's like I'm talking to myself."

Sorensen unrolled another scroll and pointed out that he had painted the bottom part upside down. He laughed whimsically at his own handiwork.

Unlike the stereotypical, introverted artist, Sorensen isn't tortured. Like a child enamored with the feel of paint, as much as the drawings he produces, Sorensen takes pleasure in the artistic process. Sometimes he paints left-handed, he said, though he's not ambidextrous; it's simply a way for him to experiment. "I'm always diving into the unknown," he explained.

Which is both a blessing and a curse.

"That's the most difficult part for me," Sorensen admitted, showing a brief glimpse of his vulnerable side. "You have to get used to being insecure."

Comments