Yes, interest in fungi is expanding. However, few of us are aware of their strange life cycles and the valuable contributions they make to the health of our forests and fields.

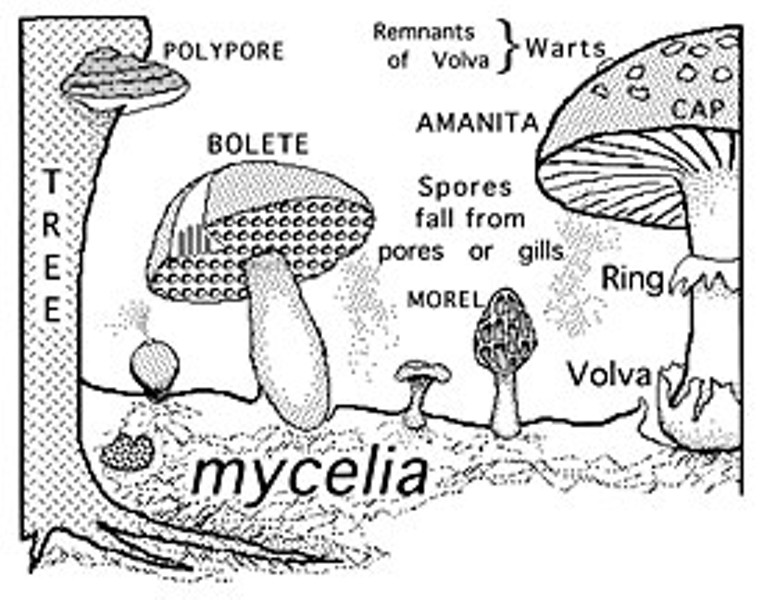

Begin with one spore produced by a typical mushroom. It is haploid, meaning it has only one set of chromosomes (like a sperm). The spore grows into fine filaments called hyphae, which branch into a web-like mycelium. Compatible hyphae from two spores fuse to produce a new mycelium containing haploid nuclei from both parents. This continues to grow, sometimes for many years. Under favorable conditions hyphae produce fruiting bodies (mushrooms, polypores, boletes or puffballs) whose function is to eject millions of haploid spores. Within the fruiting bodies haploid nuclei fuse to form diploid nuclei containing paired chromosomes. Spores develop from these nuclei by halving the number of chromosomes. Most mushrooms and related fungi reproduce sexually in this manner, but the separated chromosomes are clearly in no hurry to pair up, in the interim living long lives within their mycelia.

The mycelia of many species form intimate, mutually beneficial associations with the root hairs of many species of plants. Virginia Waters informs me that most plants — including redwoods, spruce and firs — seldom survive in the absence of mycelia, which provide their roots with water and essential elements. In return, the fungi obtain vital sugars from the plants. Importantly, other fungi obtain sustenance by decomposing plant detritus, thereby enriching the soil.

Whether delectable, deadly or even hallucinogenic, mushrooms are always fascinating and, as Virginia says, you don't have to eat them to appreciate them.

Don Garlick is a geology professor retired from HSU. He invites any questions relating to North Coast science, and if he cannot answer it he will find an expert who can. E-mail [email protected].

Comments