The ghouls, scalpels clutched in their gnarl-boned fists, hover over the operating table upon which Jack Mays, chest rent open, twists in torture. "After this procedure," the ghouls gloat, "you'll live another day and a half!"

That's one imaginary scene for a cartoon that Mays, the revered and feared longtime Ferndale artist and editorial cartoonist, says he's been thinking about drawing lately. It's a couple of days before February 2014 begins, and Mays is propped up in a bed in Eureka's St. Joseph Hospital. Clear tubes in his nose deliver oxygen, and another set of tubes, multihued like an array of colored pencils, disappears into the folds of the smock over his chest. Behind him on the wall is one of those cheerfully static watercolors — this one a creek curving gently through a green glade — common to hospitals, dental offices and motel rooms. It's only slightly more inspiring than the two plops of mush that's today's lunch. Mays has been in and out of hospitals for the past couple of months, ever since he started feeling weak and short of breath around October and learned his heart chambers are beating out of sync. Plus, there's the cancerous tumors that have begun leaking fluid into his lungs, threatening to collapse them. The doctors tell him he has a few weeks to six months to live. And he's been given a choice: have surgery to clean out his lungs and create scar tissue to keep the fluid from leaking in, which could buy him a bit of time; or get some palliative drugs, go home and ride it out to the end peacefully in the care of family, friends and Hospice.

There's yet another option dreamed up in his cartoonist mind. In this scene, once again, he's lying on the operating table. But this time the surgeons look normal, with kind eyes and paper masks, as they lean in and press a pillow against his face.

"The easy way out, you know," says Mays, his dark eyes glinting with a challenging humor. He says he thinks about these imagined scenes of his "options," and other scenes he wants to draw, all day long. "You know, having fun with it."

He isn't being morbid or melodramatic. He isn't trying to shock. He certainly isn't implying anything bad about the medical folks tending to him. He's just explaining why he never gets bored: because he's always thinking about what he's going to draw next.

And that's Jack Mays. Even near death, his mind is alive and laughing, looking forward. He credits this drive to create with helping him divert death the last time it came knocking — in 2004, when he was diagnosed with stage 4 terminal kidney cancer and given three months to live.

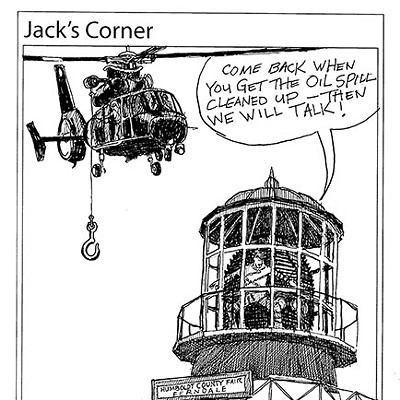

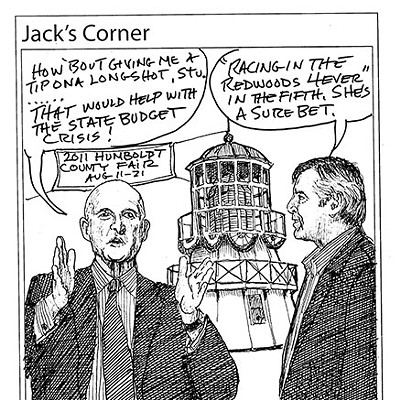

In the nine years since, yes, he's had to battle the disease. He had the kidney removed, changed his diet, tried natural healing methods and harsh cancer drugs, including chemotherapy every three weeks for four years. But he's also been living. He went to Italy and Croatia. He nursed his ailing mother until her death at 94. He helped start a foundation and became a guru to other cancer patients. He chained himself to the lighthouse at the fairgrounds to keep the Coast Guard from whisking away its historic lens. Though an atheist, he joined two churches and likes to throw curveball answers to questions raised during the Danish Lutheran Bible reading breakfasts. And he delighted and enraged his fellow townsfolk in hundreds of editorial cartoons for The Ferndale Enterprise.

Art, he says, kept him going. That, plus a positive attitude — and an obsessive love affair with Ferndale.

Mays has been drawing since he was at least 3 — when, according to family legend, he drew a football game sight unseen. He drew and painted through high school and, really, never stopped. He even went through a bird phase, some of the pieces looking like bird-book illustrations (he is a birdwatcher) and others like environmental screeds against litter and commercialism — in one of those, bald eagles wade through a sea of spent beer cans and other detritus.

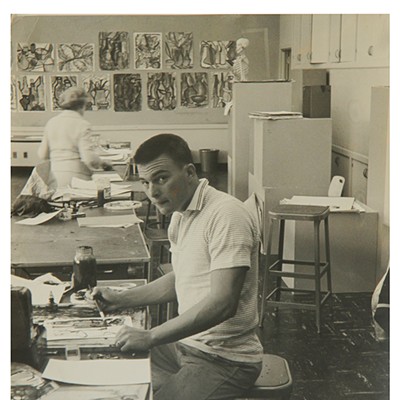

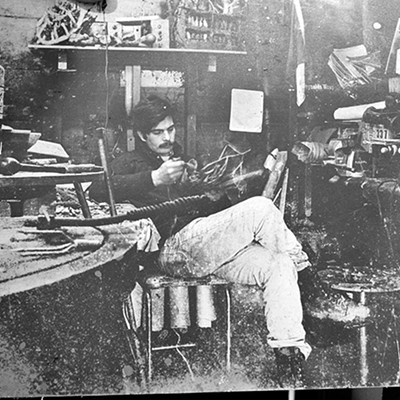

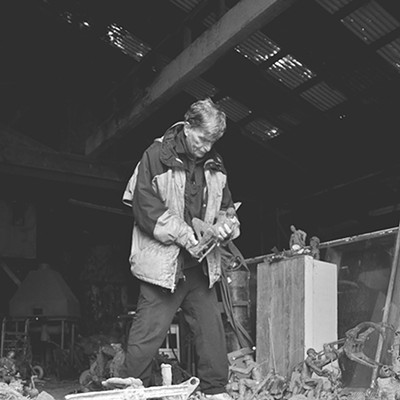

But in college and for many years after, Mays sculpted. He had a bronze foundry in the barn behind his old family home off Ferndale's Centerville Road. It was his bronze constructions of tractors and redwoods and other figures he was known for. But in 1992 when an earthquake shook his foundry to rubble, he began strictly drawing Ferndale and its people.

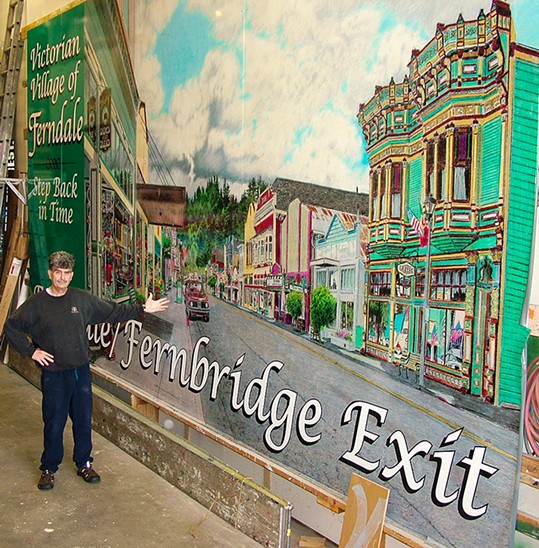

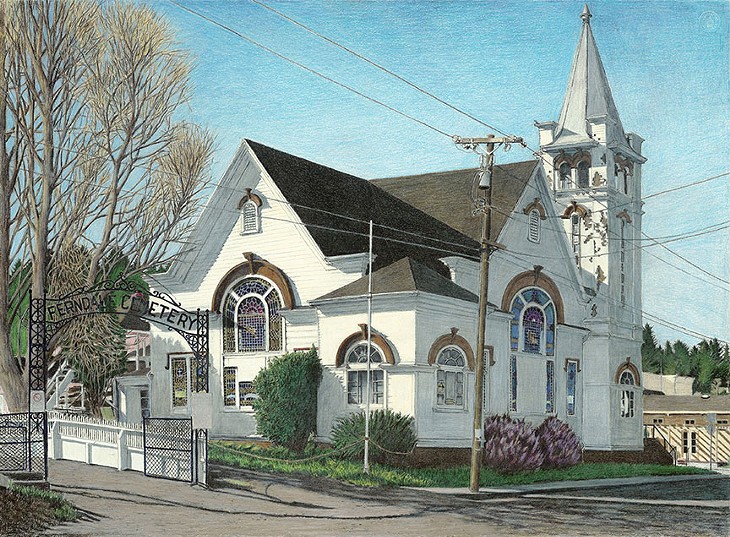

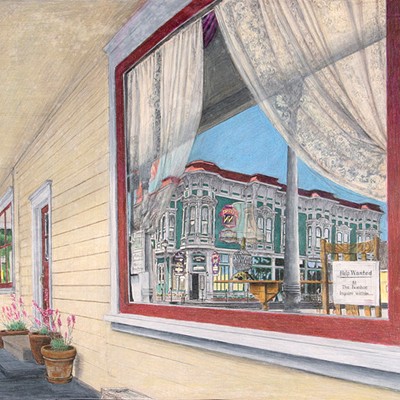

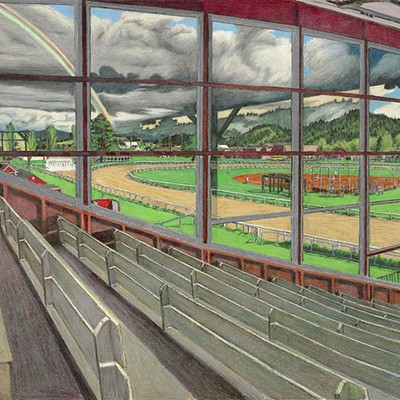

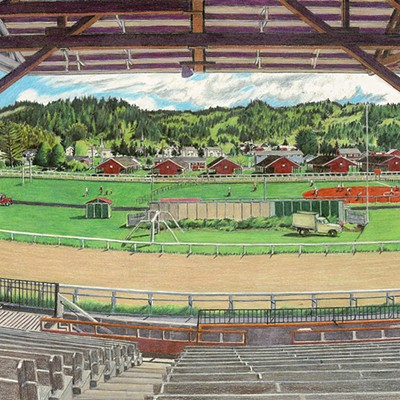

At first he worked indoors, looking out the window. Then, he says, he moved into the doorway, "getting braver and braver." It took him a while to inch fully into the open to draw; he feared he'd look like one of those guys doing "tourist art." But over time he became a familiar sight, sitting somewhere in town in his white plastic chair, drawing. He drew 12 to 18 hours a day, every day of the week — always in real time, never from photographs. He drew the ravaged town post-earthquake, and its restoration. He sat in the Ferndale cemetery for three years producing a massive panorama that includes the town and a green sweep of fields stretching to the ocean in the background. He spent several more years at the fairgrounds making drawings, including a panorama of the racetrack that seems to suspend a perfect summer in time. And he drew a restored Main Street in stand-alone canvases, triptychs and panoramas, some over several dozen feet long and, one, a 360-degree capture of downtown. The drawings are meticulously detailed scenes of streets, buildings, cars, wet skies, billowing tree shadows on sidewalks, gum drop trees and shop windows with their contents realistically interplaying with reflections including pedestrians and, often, Mays himself at the drawing board.

It required unbelievable patience.

"In my day, passion and drive was everything," Mays says. "After you graduated from college you growled and picked up your tool and went out into the world."

But when he started the complex, intricately connected drawings of town, he realized that, for him, the key was to sit still. To stay put.

"I noticed things always came at me," he says. "So I sat in my chair. And I couldn't do it intermittently. I had to persist. And that became my style." Mays became part of the scenery, "the artist," and people learned to accept that he could be anywhere, anytime, drawing — in part because he forced them to, exerting his right as observer in public spaces. Sometimes he pushed the limit. Once, Mays recalls, he walked into a backyard wedding in town and started drawing everybody.

"Someone said, 'Who let him in here?'" Mays says. "And somebody else replied, 'He's an artist. He can go wherever he wants.'"

In 1995, when Warner Bros. was transforming downtown Ferndale into the setting for the film Outbreak, Mays drew all of it, day and night. At first, he says, the movie people tried to kick him out. He says actor Harrison Ford's brother, who was in charge of crowd control, even came up to him one day and said, "I'm going to move you."

Mays told the man he couldn't do that, and held his ground in his white plastic chair.

"Next morning, I've got a really complicated drawing going, and here come the movie people," he says. "And one of them says to me, 'There's an order that you can be ushered anywhere on the sets.'"

From then on a cop escorted him wherever he needed to go. During filming of a scene in front of the Gingerbread Mansion, Mays says, the officer even cleared away a crowd of onlookers, saying, "We have to keep the artist's field of view open."

Mays also drew the setup and filming of another Ferndale-shot movie, The Majestic, in 2001, but it wasn't the star power that drew him to the sets. "The movies fascinated me," he says, "because they were such an invasion of Ferndale."

Despite his ubiquity and the fact, he says, he was always willing to help move a piano or do some other neighborly thing if asked, some residents still viewed him with scorn. He was just that guy with the wild thatch of hair and Mark Twain eyebrows who sat around all day drawing — an odd character to step around. He didn't even show the stuff, much less sell it.

"I used to refer to him as 'the bum in the chair,'" says Karen Pingitore, who owns Ferndale Clothing Co. and is president of Ferndale's Chamber of Commerce.

Caroline Titus, editor of The Ferndale Enterprise, says people always brought Mays food, and "he knew exactly when the cookies came out at the bank on Fridays, and he'd go put five or six in his pockets."

"I didn't think he was very productive," she says.

But that didn't stop her from asking him one day, in 1998, if he'd draw a new nameplate for her newspaper, which she and her husband, Stuart, had just bought. They hated the old rising-sun-over-the-ocean scene. A nice sketch of Main Street would do.

"He said, 'I don't have time for that,'" Titus says. "I said, 'Sure you do.' I kept arguing with him and finally he did it."

It's easy to assume Mays, 75, is a Ferndale native, he is so embedded in its culture. But he lived in Houston, Texas, until he was 10. Then, in 1949, his family moved to the Cream City, where they settled into the old Giacomini farmhouse on Centerville Road that Mays' mother inherited. Mays' dad, called "Honest Tex," sold used cars in Ferndale and Fortuna. Mays, a fun-loving kid, spent much of his days drawing, painting and being a bit of a prankster. Once, in high school, he put a makeshift "bomb" up the tailpipe of his young history teacher Bev Carlson's '44 Ford Chevy Coupe.

"It made a loud whistle and blew up," he says.

After he confessed, as a punishment Carlson made him erase all the drawings he'd made in the margins of every page of his textbooks. When he graduated from high school in 1956, Mays planned to join the service. "My art teacher, Dave Barnes, said, 'How about art school?'"

He went to the California College of Arts and Crafts (renamed the California College of the Arts in 2003) in Oakland, then to San Jose State University for a bachelor's degree in art. He then studied at Mills College and later got his Master of Fine Arts in sculpture at the University of Washington in Seattle.

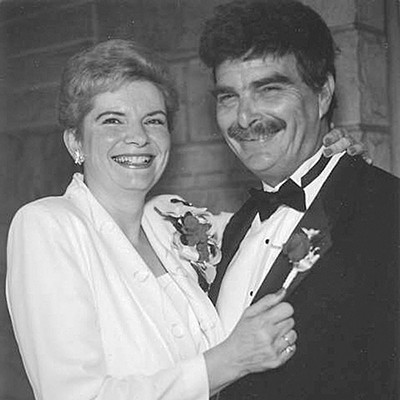

Mays met his second wife, Donna, while in Seattle. His brief first marriage produced his eldest daughter, Marcia, who is now CEO of the Orange County hospital where Mays has received much of his cancer treatment.

Donna recalls how they met.

"We both worked for Boeing Aircraft in Seattle," she says. "I had graduated from high school and had got a job as a typist. He was an illustrator. And where I sat in the office there were these double Dutch doors. He sat on the other side of them. And we stared at each other. After a month of that, he walked up to me as I was walking to my bus one day and he goes, 'Well, how are things in the typing pool?' I said, 'Oh, fine.' He asked me out and, once we went out, that was it."

They saw a movie — El Cid, with Sophia Loren — and then they went out to eat and "talked and talked and talked."

Mays taught art at a university summer school in Superior, Wis., and then at Moore College in Philadelphia. But he hated living in the big city. In 1967, he and Donna and their young daughter Michelle moved to Ferndale. (Their two sons, Ryan and Jason, were born in Fortuna. Mays' eldest, Marcia, lived with her mother.)

There, Mays built his foundry and continued sculpting in bronze, using a near-forgotten technique called lost wax casting he'd begun back east. His themes, however, transitioned from anti-war protests (soldiers, violence, the machinery of war, corrupt politicians) to ones reflective of his agrarian, forested surroundings — tractors, redwoods and logging equipment. Rents were dirt-cheap back then, he said, and soon other artists flocked to the small town.

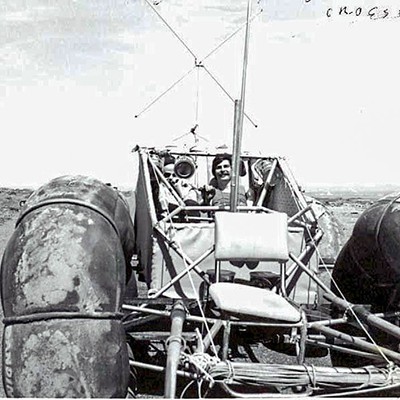

In 1968, after fellow Ferndale artist Hobart Brown showed off a fantastical five-wheeled cycle he'd built from his kid's trike, Mays built his own foot-powered sculpture — a massive tank — and, in 1969, they raced down Main Street, giving birth to the kinetic sculpture race.

Mays opened a gallery on Main Street where he sold his sculptures and prints. He had a few repeat buyers for his sculptures — which sometimes sold for thousands of dollars.

"Conditions were right for me to survive as a sculptor at that time," he says.

Mays also did a lot of metal work, including working on wood stoves, and he taught welding part time, for 20-some years, at College of the Redwoods. But he learned the most about his own art, he said, teaching drawing in a program for Ferndale Elementary School kids. He brought them onto Main Street and up into the cemetery.

In April 1992, a three-punch earthquake — a 7.1 and two strong aftershocks — knocked buildings off foundations in Ferndale and toppled structures. Mays' foundry, house and gallery were all damaged.

"I was pretty well wiped out," he says.

He was weary of sculpting, anyway, telling a Ferndale Enterprise reporter years later he had felt "slave to the process" that was "99 percent technique and 1 percent creativity."

So he told his wife he was done with it — with sculpting, teaching, gallery running, art selling. The kids were grown. The house was paid for. Now, he was just going to draw.

The Ferndale Enterprise is in a quaint house on Main Street. An old Underwood typewriter sits on a table on the porch beside two chairs with flowered pillows. Inside, a piano in the front room holds another old typewriter fed with a sheet of paper that turns out to be the newspaper's business license.

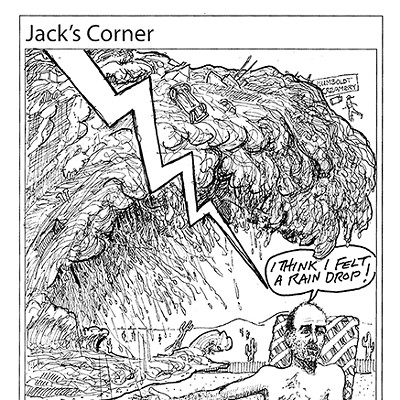

This is where, just about every Monday morning for the past 14 years, Jack Mays reported for duty to Caroline Titus to brainstorm that week's "Jack's Corner" — the editorial cartoon he started drawing two years after creating the paper's nameplate. Titus would already be thick into her reporting, and here he'd come, she says, lurching through the door like Kramer from Seinfeld.

"He'd have his oatmeal in a bowl, and a little bit of oatmeal in his mustache, and he'd have his latte because nobody makes his latte like he does," Titus says. "And he'd come in and say, 'What's happening? What have you got, Caroline? What's going on? What's the news this week? What are we doing?'"

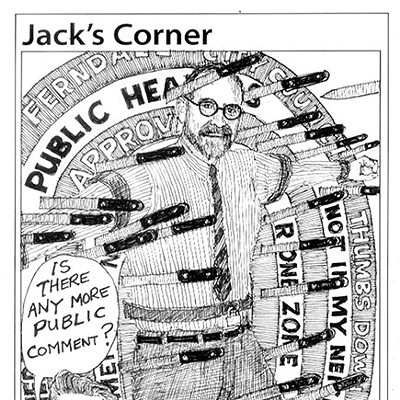

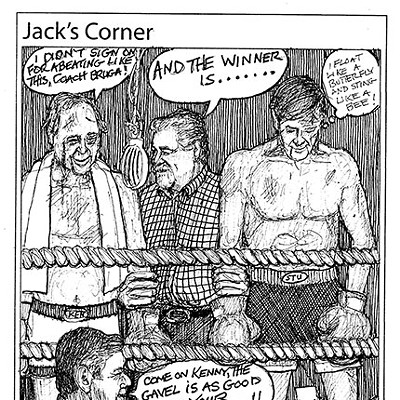

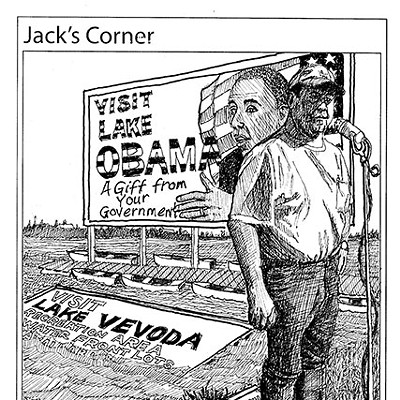

She'd give him a rundown of events and meetings and issues. He'd dig through her box of photos to find images of people he planned to cartoon about. And by Tuesday night, they'd have it figured out. Sometimes she'd have to rein in his eagerness to really bite at his subject. Other times he'd have a sentimental streak. His cartoons featured lampoons of the mayor, sharp critiques of the high school's football-happy school board and district superintendent, skewerings of the fair board, celebrations and spoofs of local dairy bigwigs, plus numerous tributes and memorials for all sorts of residents and events. He even did a series of sweet drawings of local couples after a writer set a romance novel in Ferndale.

Mays went from being the kindly, inoffensive guy painting the town's charming Victorian exterior to the social commentator poking his pen at the townspeople. He told Titus one day, taking her onto the hill of the cemetery so they could "see the edges" of town, that it was critical what they were doing. Ferndale, he told her, is a microcosm of all the world's problems. But, with its 1,300-some residents mostly clustered close together, it is also unique.

"Every issue that is happening on the national front, it's happening right here in this small community — like in any community," Titus says. "But here you can breathe it and see it, and you know exactly who the players are."

Mays likes to say that all the years he was drawing Ferndale's streetscapes, fairgrounds and cemetery, he was setting the stage for a play. Now, with his editorial cartoons, he was casting the characters. He planned, he told people, to draw everyone in town.

In 2004 came the diagnosis: cancer. Three months to live, maybe a year, tops. The town threw him a benefit party and auctioned off the first 100 of his editorial cartoons. Two years later, Mays was still alive and thriving. He'd traded a harsh, experimental cancer drug for a macrobiotic diet, supplements and daily walking, and he was cartooning weekly. He was feeling grateful. So he, Titus and Pingitore threw another fundraiser, selling prints of a dozen of his Ferndale drawings — which he'd never shown or sold before. They used the $40,000-plus they raised in one night at the fairgrounds to start the Amaysing Grace Foundation to help families with sick children finance travel out of Humboldt for treatment. To date, according to Pingitore, the foundation has helped 30 families.

Meanwhile, one of his long-time friends, Carrie Grant, was so sad he was going to die that she decided to capture his life in a documentary, One More Line, filmed by U.K. cinematographer John Howarth. Grant says she also wanted to show the community, and Mays' family, that while he was bumming around town with his white chair and drawing board all those years, he was actually creating an incredible chronicle of Ferndale. Plus, she says, Mays had something more to give, a lesson her own artist's mind needed: permission to create, unfettered.

"Jack remains, in my opinion, the purest artist that I've ever known, read about or heard of," Grant says. "He has lived his life selfishly, but without compromise to his pursuit of creativity and personal expression."

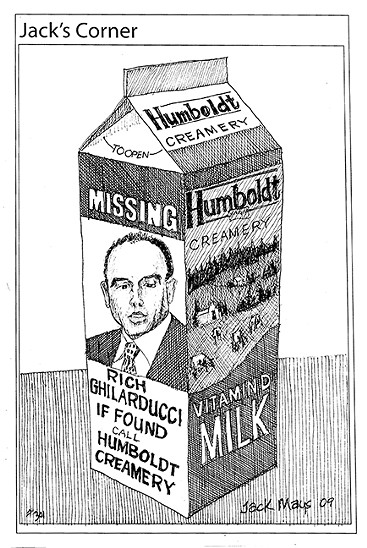

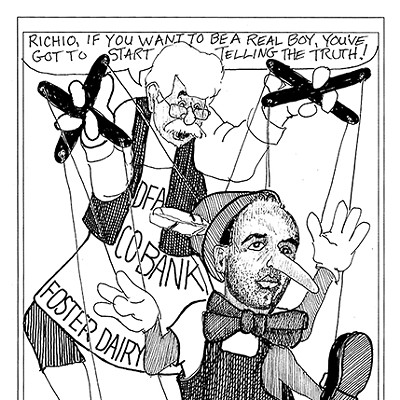

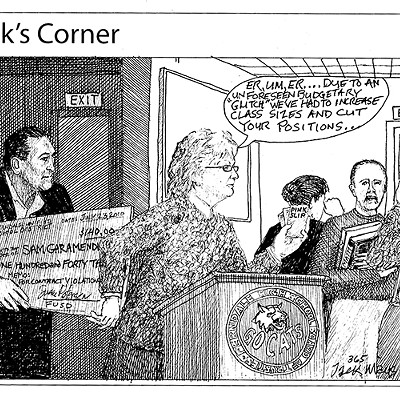

Mays kept cartooning, week after week. And after he resumed traditional cancer treatment, he sometimes drew his cartoon while getting chemotherapy. He even went to San Francisco with Titus at least eight times to cover the fraud case of former Humboldt Creamery CEO Rich Ghilarducci, whose financial mismanagement and lies led to the co-op's bankruptcy and sale to Foster Farms Dairy.

"[Mays] drew the cartoons during court," says Titus. "Then we'd run to Starbucks to get some Wi-Fi and scan them and send them to the printer."

Two of Mays' creamery cartoons won awards from the National Newspaper Association. One of them, a first-place winner, depicted a Humboldt Creamery milk carton with one of those "Missing" posters on its side emblazoned with an image of Ghilarducci, who resigned by letter in 2009 as he fled town, leaving the creamery on the brink of bankruptcy.

He always had her back, says Titus; he was always there, unwavering even when their editorials and cartoons prompted subscription cancellations, threats and even, once, an attempt to "run us over." At times, she and Mays have both had to file restraining orders. And through it all, Mays became like family. Titus says Mays and his wife, Donna, were like grandparents to her kids, who called him "Uncle Jack." Her daughter Elizabeth, 24, works at Politico now and says Mays inspired her to become a journalist.

Mays' energy, and survival, became a symbol of hope to other cancer patients with terminal diagnoses. Titus says people often call the paper asking to talk to Mays for advice on beating cancer.

"Jack was the first person I went to," said Carrie Grant's sister, Laura, in a recent email from Chicago, where she was getting treatment for the stage 4 pancreatic cancer doctors diagnosed her with three years ago. "At that time, I wanted to know how he had survived six years against all odds. I want that to be my story, too."

The most important thing Mays told her was to keep her sense of humor, surround herself with supportive family and friends, keep working at something of value and advocate for herself in the medical arena.

"The most effective strategy," Laura Grant said, "has been to keep a positive attitude and create new goals every year."

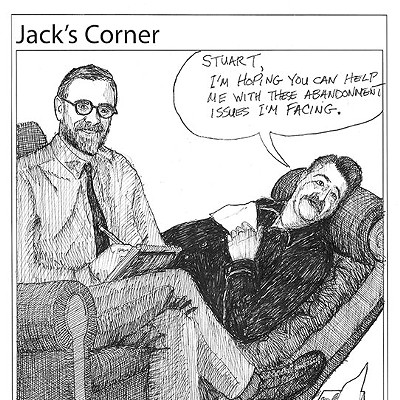

Not everyone's been entirely pleased with Mays' creative outpourings. But now, as the end seems near, even some of his targets — the folks ridiculed and called out in his cartoons — are summoning appreciation. Former Mayor Jeff Farley, the butt of many of Mays' cartoons, says that Mays was willing to "take a couple of pounds off him" in an illustration so he wouldn't look fat, and that Mays did some nice pieces about his family, too. The other day, Mays says, Kenny Weller came by to visit him. Weller ran for mayor, and lost, in a tight race in 2012 against Caroline Titus' husband, Stuart.

"I butchered Kenny in my cartoons," says Mays. "So Kenny comes in the other day to my house, after we hadn't been talking all this time, and says, 'I don't hold grudges.'"

Jack Lakin, the high school principal and school district superintendent, has been lampooned in so many of Mays' cartoons that he once said he thought that "Jack's Corner" was named after him. One day a couple weeks ago, after school, Lakin was in his office with his dog, Bess. He said he never took Mays' cartoons personally. He allowed that he and Mays had some differences of opinion on subjects, in particular football, but that he "always appreciated Jack's perspective because sometimes people's perspective is an opportunity to reflect."

He called Mays' drawings of town "truly a gift." As for the cartoons, well, he said, "People need to remember that they are in a business and their business is to sell papers."

And what of the person behind the scenes, whom some don't even know exists: Donna Mays, devoted wife of 50 years?

Donna says that like many marriages hers and Jack's has had its ups and downs.

"He's an eccentric artist," she says. "He doesn't think like other people think. Things that are important to me, like having a nice house and going on vacations, are not important to him; his artwork is, period. And his friends."

He didn't want to work, she says. He didn't want to sell his art. They had some financial rough spots along the way, and she hated living in their dilapidated, far-from-town Centerville home for so many years. But, she says, she's a loyal person and, besides, she was always too busy to get very worked up about things. She's a painter, teaches art, and for years ran a tole painting gallery with a partner in Henderson Center in Eureka. For the past 10 years she's worked at Pingitore's clothing store in Ferndale. And she loves Jack.

"He's a good person," she says. "He gets better every year. And he's been an excellent father."

Last October, Jack found a house to buy for Donna in town. She's spent much of December and January moving into it. Jack has been too sick to help. On a recent day in early February, Jack and Donna were at home. Their daughter, Michelle, was there too, visiting from Seattle. They were alone, enjoying a quiet moment in between deluges of visitors. Jack was in an easy chair, his oxygen machine burbled and breathed nearby, and he was sleepy with comfort-inducing palliative drugs. A pile of his drawings was on a bed in a back room; Donna said she can't keep them all and hopes some go to people who love them. On a desk nearby was a notebook full of drawings for a book about disgusting soup that Jack and his grandson Garret, now 9, have been creating for years. The recipes feature baby poop, poison oak, snails, roadkill and ways to get people to eat them.

Jack said he always wanted to do an art book about his life as an artist, his obsession with the town that allowed him to create art unhindered, and his survival of cancer. It would have a white cover with him on it, "blazing away at the viewer" with a bronze machine gun. "Taking it on, you know," he said.

He's also been thinking about what his last cartoon should be. Years ago, he told Carrie Grant in her documentary that it would be a tear-jerking scene of his empty white chair in the Ferndale Cemetery. Now he's thinking he'd just like to draw himself saying, a la Porky Pig, "Th-th-th-that's all folks."

Humor is everything, Mays said, if you're fighting a dread disease. So is a positive attitude. And he offers this final bit of advice on prolonging survival:

"First, get yourself a Ferndale. And then start drawing."

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4