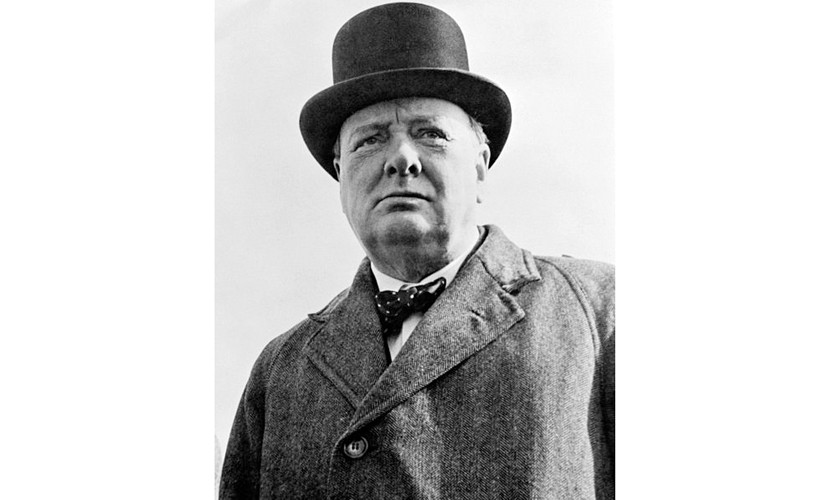

- Library of Congress

- Churchill in 1942

A reader might find much in this column to heartily disagree with. If they were to openly express their opinion in a letter to the editor, others might be impacted.

My dad -- an ardent believer in the "King's English" on which his education was based -- would have had a fit reading the previous two sentences, finding fault with four (at least!) usages.

Singular-plural commingling. How can the plural forms "they" and "their" relate to a singular "reader?" Actually, these face-value plurals have cohabited happily with their singular antecedents for centuries, helping writers avoid such kludges as "his or hers," "one's," "he or she," or the dreadful "s/he." From Iche mon in thayre degree = Each man in their degree (Sir Amadace, 14th century) to A person can't help their birth (Vanity Fair, 1840s), this particular usage has plenty of precedents. If a wordsmith like William Makepeace Thackeray had routinely penned such circumlocutions as, "A person can't help his or her birth," we might have thought less of them. (Similarly, you wouldn't say, "Amn't I in charge here?", but "Aren't I in charge here?", conflating singular and plural -- although there are exceptions, like in James Joyce's Ulysses, where Cissy Caffrey asks, "Amn't I with you? Amn't I your girl?")

End-of-sentence prepositions. Ending a sentence with a preposition (... disagree with.) has been a no-no for several hundred years. The story goes that when a secretary thought he (s/he?) was improving upon one of Winston Churchill's wartime memos by eliminating such an "error," the old bulldog wrote in the margin of the corrected copy, "This is arrant pedantry, up with which I will not put." All of us, it's safe to say, talk end-of-sentence prepositions (Who were you speaking to?) and I doubt the sky will fall if we write them.

Split infinitives. The objection to splitting infinitives (to heartily disagree, to openly express) is, in linguist John McWhorter's phrase, "a nineteenth-century fetish." (I've leaned heavily on his book Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue for this column.) This "rule" has no logical foundation -- unless you go back to Latin, whose one-word infinitives are sensibly unsplittable. Me, I'm going to happily ignore it.

Verbisms. Grammarians have long taken issue with turning nouns into verbs willy-nilly (might be impacted). Yet view, copy, outlaw, silence and worship (cribbing McWhorter's paradigmatic examples) were once nouns and only nouns. For a modern example, how long did it take, after the noun facsimile was shortened to fax, for it to be verbified (I'll fax you the proposal)? Does anyone think twice nowadays about emailing, texting, or (shudder) friending?

Sorry Dad, I know how important it was to you that people speak and write properly. You thought language was degrading to the point where we'd all end up communicating in grunts. But, somehow, the world's 6,000-odd languages have survived the relentless assaults of far uglier "lapses" than those I've alluded to (to which I have alluded?) above, and they're no worse off for it.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) vows never to ask for who the bell tolls. His books are for sale at Eureka Books.

Comments