We think of home as a place that must be built, but sometimes it's simply a place that's shaped to match a hole within us.

Some of us have holes that are shaped like an ocean coast, beaches and bluffs. Others that are shaped like forests; dense, quiet. Still others that are shaped like small downtowns, independent businesses densely arrayed along narrow streets.

Whatever the shape of home, many of us have found that some aspect of Humboldt County has fulfilled it. People stay here even in the face of a hundred objective reasons to leave. The money is better elsewhere, as are the nightclubs, as are the research hospitals. It's easier to travel from elsewhere, and cheaper, too. There are more theaters, more concerts, more diverse opportunities for the kids. People make home in Humboldt County because of something other than what the economists would count as "rational self-interest."

But when some other hole in their lives becomes more apparent, people also leave Humboldt for new homes, departing with a mixture of anticipation and regret. Their pursuit of opportunity elsewhere is paired with lost opportunities for those they leave behind -- distant (or lapsed) friendships, skilled and thoughtful people no longer contributing to our economic and civic life. Home is a complex calculus for all parties. How do we balance the equation? And what do we see when we look back at what we've left?

[][][][]

As with all relationships, the end is bittersweet. Ellen remembers the day she left in 2007. "I knew it was the right thing for us, but I knew I was leaving so much. I had the cats in the car crying along with me."

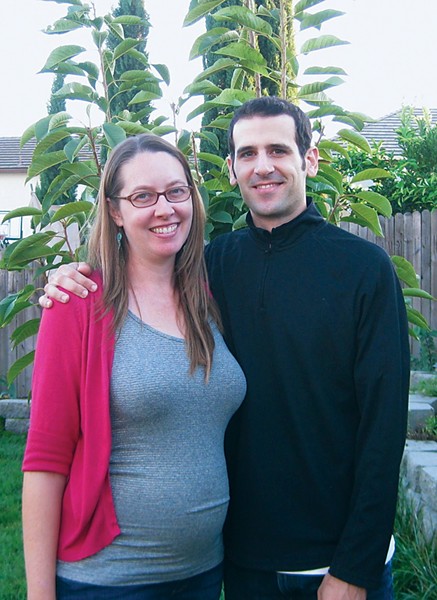

Ellen and Eryn Pimentel sit close on their couch in West Sacramento, leaning into one anothers' shoulders on a late November day. They bracket their beagle/pitbull Dolce between them. Eryn is tall and lean, Ellen shorter and just beginning to show her pregnancy; Dolce is a little long between the shoulders and head, like a beagle with a front-end extension kit. They're clearly at home with each other, but it's less clear how they negotiate their choice to leave Humboldt for Sacramento. When a home is true to us, it fits us like a lover's voice. When a home is false, it is an ache that doesn't subside. How likely is it, really, that two people's home-shaped openings would match?

In 1998, Ellen and Eryn arrived in Arcata from high schools in the Central Valley -- Eryn from Tulare and Ellen from Stockton. Their interests in environmental science made Humboldt State the obvious college choice. But although they shared the same major, college and city, they had different experiences right from the start. Or even before ...

"I had actually been to the area several times," Ellen said. "My dad's family lived in southern Oregon, and we went on long summer vacations. When we were coming back, my sister and I always asked if we could drive ‘the pretty way,' through 101 and 299." Ellen remembers camping at Jedediah Smith State Park, remembers the trips she took with her grandmother to Crescent City. So she may have been predisposed to have a good Humboldt experience.

"The thing that surprised me was how nice everyone was," she said. "I came from an area where you don't really make eye contact on the street, but in Humboldt, everyone you see says hi to you and smiles. I don't remember very long where it didn't feel like home. I loved the area, loved the people, the surroundings. ... Every single day I had at least one moment where I was so happy to be living there."

Eryn, by contrast, had arrived blind in Humboldt; his entire exposure to the place consisted of the photos of redwoods and forested hills in the HSU recruiting pamphlet. "I didn't really know what to expect before I came to the place for freshman orientation, the week before classes. I went there on faith."

Once he arrived, he realized that the alluring photographs may have concealed something important. "When I was first up there, it was cloudy and overcast a lot. I wasn't expecting that," he said. Aside from the perpetual-hoodie weather, he also discovered a social life far different than his native Tulare. "The people were different, the environment was different, the attitude was different. I'd never encountered hippie culture before I got up there... the dreadlocks, the hemp necklaces." Most of his new college friends were also from away; they shared that experience of being strangers in a strange land, and stayed mostly to campus life.

Although they were at HSU together for all four years of college, Eryn and Ellen didn't meet until 2002, as they were both finishing their first degrees. Ellen had remained with her environmental science major, but Eryn had changed programs and graduated with a degree in art. And while good jobs are hard to come by in Humboldt, good jobs for the liberally educated but unspecialized are even harder, so Eryn moved back to Tulare with his parents after graduating. Ellen found seasonal work in Humboldt doing plant surveys, ecology assessments, invasive-plant management. She worked on both sides of the eco-divide, as a botanical technician for Green Diamond Resources (formerly Simpson Timber) and as a contractor for the Fish and Wildlife Service. "I loved Humboldt. I really loved the work I was doing at the time, even though it was seasonal and not permanent."

Even apart, the two of them realized that they were in love, and also both thought that a second degree might help their economic chances. Eryn returned to Arcata, and they went back to school; Ellen for a master's in biology, and Eryn for a second bachelor's degree in geography. "Science and art have always been my two loves," he said. "Maps combine the art and the science." But although Eryn had found college studies that he loved, and was living happily with Ellen, he could foresee that he'd always struggle for relevant employment in the Humboldt economy. "There were a few jobs associated with parks, a few with timber companies, a few with government agencies like planning departments, but not a lot. I did a lot of job hunting." And he made sushi at Tomo, biding his time.

"Getting engaged was a big turning point," Ellen said. "I was trying to convince Eryn that if we stuck it out, he'd find something. But we were getting married. We wanted to work in our field, make some money, buy a house, that kind of stuff."

Ellen found work first, and they moved to Sacramento in 2007. Six months later, that same firm had an opening for a GIS specialist, and Eryn was hired. They bought a house in a 2004 development in West Sacramento, built when it seemed like Sacramento and the Valley would expand forever. It's designed in our contemporary "contractor Modernist" style: "his-and-hers" single garages attached to either side of the house, mini-blinds in the windows, walls that come together in sharp edges. But they've filled it with Eryn's paintings and a collage of framed photos upstairs in the hall, a cheerful miscellany of sizes and proportions and families and generations. They've used their environmental knowledge in a local way, planting trees and vegetable gardens in their back yard.

So life seems good. Careers, house, dog, yard, baby soon to come. But are they home?

"We like being here," Eryn said. "We're close to everything and our families, we have great friends, close to the wilderness. We're about a three-hour drive from my family. It's the perfect distance from my parents."

Ellen: "This isn't the grand life plan. When my parents saw the place, my mother said ‘I can't imagine you ever moving away from here,' and I thought ‘well...' This is not our forever home. I can see being here for 10, 15, 20 years and then moving closer to the coast. But it's a nice place to be for the next five or 10 years."

Even across two sentences, her window of duration closes down.

"We have good jobs, we have a house, we have a baby on the way. And I don't hate Sacramento, which I thought I would."

"Ellen says she'd like to retire and live up there one day again," Eryn said. "We'll see if that happens, if we're ready for a change again."

"I made him promise we would retire there," she said. And then to Eryn, almost too quiet for me to hear, "You probably don't remember saying that ..."

[][][][]

Humboldt County is a place of diverse and conflicting meanings; each of us chooses the image that suits our needs. We speak of its small towns as places of limited careers and limited ideas, or as places of slower pace and tighter community. We can be enchanted by the magical appeal of remote lands, untouched by time, or frustrated by the isolation of a place difficult to access by vehicle, freight or media. We can speak of the draw of the metropolis for young people on the make and on the move; or of the opposing draw of the small town for raising a new family.

Regardless of the frame we use, it's easy -- and incorrect -- to see Humboldt as a relatively unchanging place. The county's population has grown only moderately over the past 30 years, averaging about 6 or 7 percent growth each decade since 1980. But Humboldt's relative stability hides a continual flux. Humboldt State University draws a couple of thousand new students each fall, and a somewhat smaller number graduate each spring. Some remain in their enchanting new home; others go on to opportunities elsewhere. The other major industry also brings an ever-changing workforce, in the fields and grow houses and trimming rooms and glass shops. And the quiet, small towns breed crops of young people who we then educate out of ranching and timbering, kids we urge to "broaden their horizons" rather stay within the limited futures that Orick or Loleta have to offer. Over the past 10 years, the county has gotten older as those young people move away; there are fewer people under 18, more over 65.

Humboldt has changed in economic ways as well. The number of adults with a college degree has increased 30 percent, from 18,755 in 2000 to 24,455 in 2010. And the median price of homes sold nearly tripled from the start of 2000 ($117,500) to the peak of the housing bubble in March of 2006 ^$349,500) before falling back down to $250,000 by September of this year. But even with the higher education levels and pricier housing, incomes have barely kept pace with inflation, and hover at about two-thirds of the state average. To put this in terms that make it clear what young people face here, the median Humboldt house price in 2000 equaled 7.8 times the per capita income; in 2010, that house cost 13.9 years of per capita income.

But the demographer's facts and data can conceal the specifics of real lives and real motives. Humboldt's changes take on more subtle shades when we see them through particular lenses.

Daniel Davis grew up as a PALCO kid in the company town. When he graduated from Fortuna High School in 1999, he was gone immediately. "On a personal level, my dad and I weren't getting along. He was an alcoholic; we had a lot of family dysfunction. Also, I was personally ambitious. I wanted to get out into the world. Not Scotia. I wanted to get out and see and explore. My dad just wanted me to go to CR and work at the mill."

Home is a complicated idea, just as each of our homes is a complicated place. Home is the site of love, and of aloneness. Home is where relationships are nurtured, and where relationships are spoiled. Home is where our aspirations can take root, and where our aspirations can be denied. Home can be shelter, or a trap to escape.

For college, Daniel stayed close to home in one way: he chose a religious school that was part of his childhood denomination. But he also chose a place that was the mirror image of his childhood home. Scotia was old, enclosed and rainy; Costa Mesa was new, open and bright. "I was excited to be in the city and sunshine; everything was pretty. It just didn't look as run-down. There were palm trees, buildings more than four stories tall, restaurant chains. More channels on TV."

Orange County, and religious life, seemed to suit him. He stayed in Southern California for his master's degree in biblical and theological studies. But family brought him back; his father had been diagnosed with cancer, and Daniel moved back home, to tend both to his father and to their relationship. His definition of home was in flux, neither entirely working-class Scotia nor Type-A Orange County. "I worked at a megachurch down there, and I was so depressed at the way they did things. After growing up in these little churches, I wanted to do it that way. And I was kind of entrepreneurial. I got a grant for $90,000, brought some people up from Orange County, and started a church here."

As part of that ministry, Daniel went back to school once more. He began a master's degree in sociology at Humboldt State, mainly as a way to be connected to the school and its students. "But it started expanding my worldview. It became more meaningful as time went on. There was a passion that I didn't have before"

He's now teaching sociology as an adjunct faculty member at HSU, and he's discovered a growing interest in higher education administration. And as Daniel is working to define himself, he's also working to define home, this time more purposefully. "I could stick around and try my odds at being an adjunct and seeing how that leads, but I don't want to risk my whole career on that thing of spending your whole career in one job, staying at HSU or CR and hoping that they'll have the right job open up." He'd seen how that one-job career in a one-company town had limited his father's horizons.

His wife Rachel, also a '99 Fortuna High graduate, is in human resources at St. Joseph's Hospital. "There are good jobs up here for people who have skills like that," Daniel said, "but it's hard to get those experiences here. ...That HR department doesn't have 20 people, so it might be a long time before a more senior job opens up, and that next step may be a big jump up. There is a career ladder here, but it has rungs missing." He and Rachel are exploring San Diego, with its multitude of colleges and health-care institutions, as a place where they both might find meaningful work.

They now also have a daughter, 3-year-old Madison, and being a father has revealed other mixed blessings of Humboldt County. "Being with family, things are slower, you have time for people. My daughter has her grandparents here ... grandma and grandpa have her a couple of days a week. The things I appreciate now are different than the reasons that brought me back." But being a parent also evokes his childhood feelings of suffocating enclosure. "Scotia was sheltered from Humboldt County, which was sheltered from America," he said. "Raising a daughter here, there's only people's houses to go to or the beach, not museums or places with ideas. ... I just worry that if we stay here, it'll be all family and Little League and walks in the park."

So Daniel makes plans for a new Southern California life, pulling together applications for doctoral programs across the schools of San Diego. But he doesn't have the same unequivocal feeling of escape that led him away in 1999. "I have a real love-hate relationship with this place. When we leave again, I'll miss it more this time, because I appreciate it more. Last time I just wanted to get the hell out. But I'm just not sure it's enough."

[][][][]

Even though it's often true, it's far too easy to say that people leave Humboldt for better jobs. "Better jobs" means many different things. For Eryn, it meant the ability to work in his field and escape the low wages and everyday hassles of food service. Ellen spoke of a house and family and good work. Daniel wants the opportunity to climb side-by-side with his wife up career ladders with more predictable rungs.

For others, "better jobs" means something very different. There are people with ideas that they couldn't fully express here, ideas central to the ways they defined themselves.

"I knew I would have to leave someday if I wanted to get serious about my music career," Melody Walker said. She'd come to Arcata and HSU in 2003, changed her major from political science to music, and was an integral part of at least three local bands: the vocal group AkaBella, the Afro-funk orchestra WoMama, and the samba troupe Bloco Firmeza. She was playing three or four nights a week with one or another of these groups.

Melody and her band-mates were successful, in terms of audience reception and booking new gigs. But "successful musician" in Humboldt terms can take on a unique definition. How much money was she making from her music? "Well, you might as well call it zero. All three of the professional groups I was in were in a phase where we were reinvesting in the band; buying sound equipment, saving money to record a high-quality CD. Occasionally AkaBella started being able to pay ourselves, but very little; you're talking $20 a show." And success revealed some tensions. "Half the band was homesteading and half was itching for fame. You can guess which half I was in. And to be fair, it's like that in any band; 90 percent of every band in the world has some homebodies in them, and when the chips are down, you find out who's on board."

Melody now lives in Richmond with her musician boyfriend, teaching and performing, about to release her first solo CD. But she knows that in her line of work, only three cities really matter: New York, Los Angeles and her likely destination, Memphis. It's only a matter of time before she heads to an even bigger home.

James Marvel also needed that larger stage, though he practices a different craft. His childhood is a litany of momentary homes: Eureka, Napa, Arcata, McKinleyville, Arcata, Potter Valley, Willow Creek. Like many disrupted kids, he learned that his lasting home was shaped to fit ideas rather than places. "I took a world religion course (at College of the Redwoods) with Rabbi Les Scharnberg. We became pretty good friends, corresponded outside of class. I did well in the course, and asked him what I should do. He said ‘you should take a philosophy class.' "

He did. And then went on to an undergraduate degree in philosophy and rhetoric at Berkeley and a master's in philosophy at Boston University. He is now halfway through a law degree at Syracuse. "A lot of it is just exposure to ideas, in a very literal way. At Berkeley ... meeting all these phenomenal and super-intelligent people who have influenced me. There are people like that in Humboldt, but you have to seek them out. You won't come across them in general."

A body of research has shown that small places breed generalists, people who learn to pitch in and do a lot of things pretty well simply because there aren't all that many people and there's a lot to do. Large places reward specialists; there are so many people in the Bay Area or Seattle that you need to be hyper-focused to be rewarded in your field.

Don Speziale is another Humboldtian whose specialization has drawn him to a bigger venue. He grew up in Arcata's Greenview neighborhood, a third-generation Italian-Arcatan. His mother had a lifelong career at Wells Fargo Bank; his father had worked at the California Barrel Factory until it closed, then joined Safeway and stayed there until his own retirement.

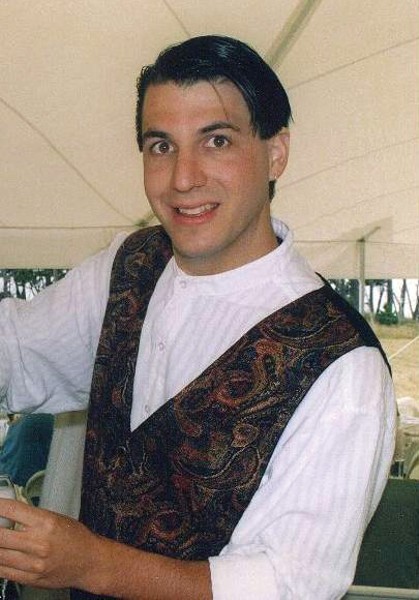

Don went to Humboldt State in 1984 after graduating from Eureka's St. Bernard's High School "because it was close and familiar. I was still trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life." He took advantage of the theater program's relative smallness to take up every possible work, acting and production and direction and tech, learning the whole of the business.

Don then took his double major in theater and English into teaching, leading the drama program at Eureka High School for three years in the early ‘90s, and he truly loved his work there. But he had an odd premonition. "I was working with people who'd been teaching for their whole lives. They were great people, but they were waiting to retire. And I pictured myself doing that, I put myself into that, and decided that it was time to get out of that situation even though I loved it."

He stayed with theater, though, training himself directly for the profession. He was awarded a space at the American Conservatory Theater's Advanced Training Program in San Francisco, and got his master's of fine arts in acting in 1996. And the city was good for him in other ways. "During those two years, there were things I needed to figure out about myself. I got to come out of the closet, and to do that with my folks. I got to meet people like me in the city. I didn't have much of that in Humboldt; it was still a different time then."

But as large as San Francisco may seem when compared to the drama department of Eureka High, it still isn't at the pinnacle of the creative arts. "You can talk to anybody who's lived there for a while; San Francisco isn't that big of a city. The opportunities to make a living at acting weren't always there."

Don had also begun writing, and his screenplays led him to Los Angeles. He has a script in movie development now, called The Pleasure of Your Company, about the varied people who come together to attend a wedding and the ways each finds different meanings in the event. He hasn't left his day job with Blue Cross of California, but he's at the culmination of over 15 years of success in his real vocation.

"I always wanted to do more," Don said. "And you have to experience it to know what ‘more' means. ‘More' means something different to everybody. I couldn't be as free with my sexuality. I needed to experience what it meant to be in a bigger community of that. And to navigate something bigger. Here in LA, I love to explore, find new neighborhoods. I'm still finding new places all the time. In Humboldt, you figure things out, and you know the place. There's only so many times you can walk to the Plaza, unless you're really attuned to that, doing the four or five things that make you happy."

[][][][]

It seems rare that the departure from Humboldt is painless. Mellisa Hannum, who left Arcata for Nevada City in 2007, says "We still haven't given it up. I still have the North Coast Journal and the Eye and the Times Standard on my Facebook page. I know what's happening in Arcata as well as I did when I was there." Her partner Charles Brock added, "One of the reasons why I haven't gone back since we left is because I don't want to get sucked back in again." Don Speziale carries an image of the Community Forest as the wallpaper on his smart phone. James Marvel has his grandmother's framed photo of Fernbridge mounted prominently in his Syracuse apartment.

I know those feelings well. I left Arcata in 1998 for work in San Luis Obispo, then in Oakland, then in Durham, N.C., now in Boston. And Humboldt County is still closer to the shape of home for me than any place I've lived since my childhood.

I came back for a week last summer, and could still find things on the shelves at Wildberries, remembered my way around the trails of the Community Forest, let my car drive itself between Arcata and Eureka as I looked once again at the mud flats of the Bay, dotted with egrets and pipers. Many of the stores on the Plaza and in Old Town Eureka were different, but the places themselves were just as I'd left them, dense and detailed, their congenial sidewalks filled with conversations to join or overhear. I went back to places that figured in my books, remembered the friends I knew there, so many themselves now gone. For all of us, Humboldt is now a phantom limb, its absence accommodated more or less successfully, but occasionally surprising us with its immediate, tactile presence.

Herb Childress lives outside Boston and is dean of research and assessment at the Boston Architectural College. He left Humboldt in January 1998; scarcely a day has passed that he hasn't longed for return.

Comments (15)

Showing 1-15 of 15