You might see them busking on the street in Old Town, picking and singing in cafés and clubs, at open mic nights, jamming on a back porch, in a garage or a living room or on some festival stage -- musicians of a wide range of ages and caliber living the folk life in their fashion.

They may not identify themselves as “folk” musicians, and who’s to say what that word means anyway? Webster defines a folk song as “a traditional or composed song typically characterized by stanzaic form, refrain and simplicity of melody,” but the word folk alone comes from Germanic roots and simply means “of the people.

One thing for certain, there are plenty of people in Humboldt playing music with traditional roots. A fair share of them play string instruments -- guitars, fiddles, banjos and the like. Some play, to varying degrees of success, traditional music that was popular in America’s southern mountains in the early part of the 20th century. Others favor tunes with Celtic roots, the jigs, reels and hornpipes that influenced the Appalachian sound.

The cream of local traditionalists and song composers, scores of them, will be performing out in Blue Lake and/or in Bayside between July 15 and 21 for the 29th Annual Humboldt Folklife Festival, a local tradition with deep, deep roots. You’ll find a full schedule of events in the center of this section. But first we’ll introduce you to some of the players who will be there picking, fiddling or making music in some fashion.

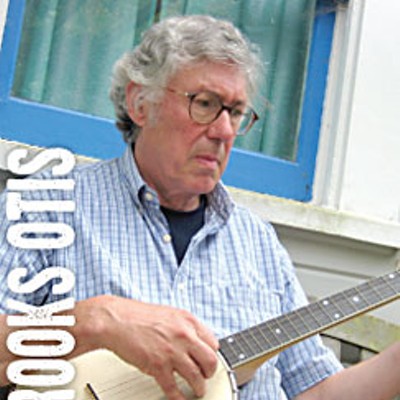

The Quiet Man

*Brooks Otis is a quiet, unassuming guy who’s played a major role in the local folk scene and in Humboldt’s arts world in general, serving on the boards for both the Humboldt Folklife Society and the Humboldt Arts Council. Otis’ folk credentials go back decades. For 30 years, he ran the premieracousticmusic instrument shop, Wildwood Music, with Mike “Spumoni” Manetas (mandolin player for The Compost Mountain Boys) before the two of them retired a few years ago to turn things over to a new generation. Now Otis spends his time playing in a number of bands: clarinet in a jazz combo, pedal steel in a country band, fiddle and banjo in an old timey outfit. He also plays roots music on the radio as host of “Monday Variety Pack” on KHSU.*

What will you be doing at the Folklife Festival?

I’m teaching three workshops -- beginning old time fiddle (my version of it), bluegrass banjo (because I do that) and I’m teaching twin fiddle with Judy Hageman. I’m playing with two bands, an old time band with Judy and others that we call Clean Livin’ Band because we play once a month for Arts! Arcata at Bubbles [a local soap shop]. And I’m playing Saturday with The Country Pretenders, with Fred [Neighbor] and Joyce [Hough], playing [pedal] steel guitar. It’s a band that just plays occasionally. All of us love the old country music from the ’60s: Merle Haggard, Buck Owens, things like that.

Do you consider yourself a folk musician?

Without going into a long definition of “folk,” I’m a musician who plays in styles that are considered by some to be folk music. I see pure folk as music that’s been passed down from father to son in a relatively restricted environment so it maintains some thread. For example, it could be music you’d hear in some part of Appalachia or in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, or in some other generationally and socially stable areas. That kind of music is based on old styles -- old time string music, Appalachian fiddle tunes, music derived from antecedents like Scotch-Irish music, black blues ... Roots music, to put it simply.

How does this folk or roots music fit into Humboldt County?

I would say it fits in just the way it would fit into some county like Los Angeles. You have people who, for whatever reason -- personal choice, exposure -- find themselves attracted to earlier, simpler forms of music, which could be called folk music. For example, you might have someone influenced by something like pre-electric Bob Dylan, which is not the same as being influenced by Round Peak fiddle and banjo styles of the late 19th century.

I’d say you find people interested in this sort of thing everywhere, not just Humboldt County, people who like specific styles of music, who form bands. Some gravitate toward Celtic music, some to bluegrass, some to more electric country like what The Country Pretenders do, and on to the kind of thing that Jason Romero does with Striped Pig, following a very specific interest. He and his friends studied it together and figured out “This is the kind of music we want to play,” and they play it.

The President

Patrick Cleary is president of the Humboldt Folklife Society, and thus is intimately involved in organization of the Folklife Festival. His “day job,” as he puts it, is overseeing several radio stations: KHUM, KSLG and The Point. “And I’m an amateur musician,” he adds.

Cleary will serve as host for Folklife’s Songwriter’s Night on Tuesday, July 17, where he’ll pull out at least a couple of his own songs, accompanying himself on guitar. He also plays mandolin, he’s learning stand-up bass and is a self-described “mediocre banjo player.”

Do you consider yourself a folk musician?

Yes.

What does that mean?

I take a broad definition of folk music. I go back to Big Bill Broonzy, who said, “It’s all folk music; I ain’t never heard a horse make none of it.” I tend to look at folk as some form of acoustic music. That’s generally where I draw the line, but I’m not real strict on it.

Why do you think folk music plays such a strong role locally?

That’s an interesting question. I think part of it is that this is still a rural community to some degree. I lived in New York City, I came from there, and you know what? You don’t play banjos in New York City. They just don’t sound good. (Laughs.) So I think that’s one element.

The other part is hard for me to put my finger on. I think it’s stronger here than other places. I argued with Brooks Otis once that there are more Martin guitars here per capita than any place else in the country. Brooks, who probably sold most of them, thought about it for a while and said, “Well, Galax, Virginia might have more.” [Galax is an old timey hotbed known as “Gateway to the Blue Ridge Mountains.”]

There are certainly a lot of musicians here and folk music tends to be a participatory kind of thing. It’s easy for people to come together for a jam. There’s a relaxed nature to the scene.

Returning to the question of what folk means -- In the context of the Folklife Festival, how do you interpret it?

I’d say the festival has evolved over the last few years. As to what we’re trying to do, we’re showing off our local musicians. When I first started running it back in 2000, we used to bring in guest artists. We’ve evolved away from that to be a showcase of local people to show off the music of this region, if you will. And we’re certainly not strict in our definition of what that is.

So it’s regional music in the same way that Dell’Arte describes itself as “theater of place.”

Yes, this is music of place. There’s a general rootlessness in society these days: People move around a lot more, and the sense of place has become the same in a lot of the country. Being a New Yorker who’s moved to Humboldt County, I’m struck every time I leave here how homogeneous America has become. Humboldt County is really unique in that we’ve resisted that.

People here seem to be interested in getting in touch with their roots. They look back and grab on to their roots to find some sense of “Where do I come from? And what makes me different in modern day society, which tends to be going 100 miles an hour?” You get to old time music where you can play a D chord for an entire song and there’s something grounding about it.

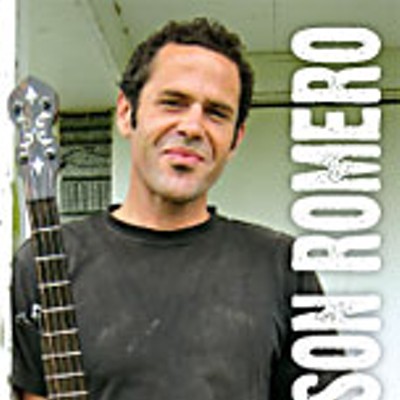

The Banjo Man

Jason Romero is all about the banjo. He builds banjos for a living, and we’re not talking casually -- the instruments he lovingly crafts in the “J. Romero Banjos” shop behind his house along Humboldt Bay are in the hands of stars like Ricky Skaggs. He also plays bluegrass banjo for the venerable Compost Mountain Boys and old timey style in The Striped Pig Stringband (formerly known as Devil’s Dream). Both of those bands are playing Thursday, July 19, for Folklife’s Backyard Bluegrass in the Rooney Amphitheatre; he’ll also be sitting in that night with Clean Livin’ (see the Brooks Otis interview for details).

The next night his main band, Striped Pig, plays at the Bayside Barn Dance with a square dance caller directing dancers. It’s a dream come true for the band, who focus on a very specific style of music from one particular area in the Appalachians.

Do you consider yourself a folk musician?

Yes, in a broad sense. I think of folk music as traditional music. And so I’m definitely into, and surrounded by, traditional music. I came to it through the instrument. For me it was the banjo first, and then from there I started to explore the music. But I first got fascinated and fixated with the banjo itself. I don’t know why. I think a lot of banjo enthusiasts just... well, they don’t know. They just love the sound of it, the look of it, just how much fun it is to play.

Why the fascination with this particular type of music? And why here in Humboldt?

Why the specific kind we play? I don’t know that that’s really the case. I mean there’s a lot of people playing fiddles, banjos and guitars, and playing acoustic music, and being inspired by a lot of the music that was recorded first in recordings in the ’20s and the ’30s. But as far as the kind of music that Striped Pig does, I mean specifically from the Southern mountain repertoire, in that real strong fiddle/banjo tradition, I don’t know if there’s a whole lot of people around here that are playing that specific stuff.

How specific are we talking here? I’m told you guys focus on music from one particular county in North Carolina.

Yeah, it’s the Round Peak area. Tommy Jarrell, who’s like the top fiddle player who everybody else copies and who’s inspired countless other musicians -- he’s from there. And Fred Cockerham. A long list of [great] musicians came out of that area ... Round Peak had a sound because they were all kinda friends, and it wasn’t like one valley where there’s one obscure fiddle player learning only by himself. The tunes they played are the same, but they all played them just a little bit differently. That really fascinates me. It’s weird that I’ve never been to the South, but I’m totally in love with this music. I was thinking: Why do I love this music so much? It’s just so hard to explain why you just love something. It just excites me.

So do you think that Humboldt County has a sound?

Humboldt County? A sound? No, I think it’s just so diverse here. There’s so much up here, that’s what I love about this area. It’s such a small little community and such a diverse and vibrant music community. You know you can go hear authentic samba drumming and West African drumming and soul music and great traditional Irish music. Everybody’s in their own little world and just totally excited and geeking out about their music.

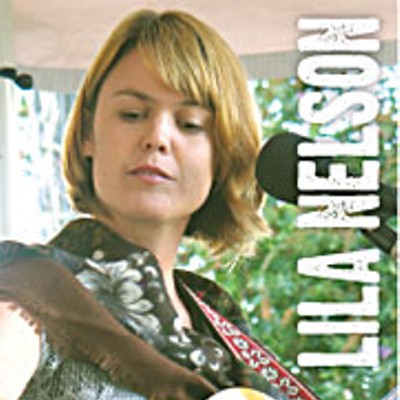

The Ironic Wrong-Righter

Lila Nelson is a sophisticated down-home singer/songwriter, if that’s possible. Born in Michigan, raised in SoCal, she lives in Arcata with her husband Ian Calindo. Humboldt is home base, but she spends a lot of time playing in clubs all across the country. She has three CDs out at this point and is working on a fourth with Kenny Edwards from The Stone Poneys handing production. Putting on an ironic tone, she says she’s “a singer/wrong-righter. I right wrongs through songs. No, but wouldn’t that be nice?” She does write the occasional topical song -- her most requested number, “Dirty Magazines,” has feminist tendencies and her subtle protest song, “Fresh Paint,” is featured on Neil Young’s Living With War website -- but she’s more likely to pen poetic tales of relationships and the like.

What are you doing at Folklife?

I’m doing a set on the main stage. I’ll be playing my own songs, songs I wrote. I compose songs. And I’ll also be doing some emceeing, apparently.

Do you consider yourself to be a folk musician?

Yes. Sometimes. What did Bob Dylan say? “To sing a folk song you have to know all of its hundred faces.” I think part of that comes about through writing. When you write folk music you use pieces and parts of other songs. You acknowledge where you’re coming from historically. You say, “Oh, I stole this chord progression,” and that’s OK. You accept the history of it. Although, Joni Mitchell would say she has no influences.

You also do a “folk music” show on the radio [“Meet Me in the Morning” weekends on KHUM].

I do. And that’s also broad. I use it as a springboard for getting acoustic music and traditional music out there. Is that folk music? I don’t know what folk means. Honestly, I hate being called a folk musician. Shhh. Shhh.

Do you?

It’s limiting to be called anything, to have someone say, “This is what you do.”

Having toured the “folk” circuit nationally, would you say Humboldt has a higher than average number of folk musicians?

Again the word “folk” is a broad term that’s used for all sorts of music. There are a lot of old time musicians per capita coming out of their kitchens and bedrooms and out of the woods with their banjos and fiddles and old time instruments. There are new avenues for that; people are embracing it again. It feels very at home here because we have the woods and the mountains and so forth, but I see it happening all over the country.

I think part of it might be in response to technology advancing so quickly. You could say it’s a reactionary response: People going back to their roots, and not just with old time music, with all music. People in general are embracing their roots.

I love the notion of music embracing historical elements. Part of that is a reaction to things like downloadable music and seeing music get further and further away from a tangible source. People remember that live music is always out there happening, and that it’s a way to make community happen, to be together face to face. (She slips into a faux accent), So , this is the magic of folk music.

In the Family

Ken Jorgenson and his wife Maria McFarlin run a folk music-oriented business in Carlotta making and selling soft-shell instrument cases for string instruments. They also play in a country swing band called Falling Rocks: Maria on bass, Ken on guitar, their daughter Gina Ginochio on second guitar, a couple of other friends, everyone singing in harmony.

What are you doing at the festival?

Maria: We’re playing swing for the barn dance Friday night at the Bayside Grange, then Saturday we play at 3 p.m. And Ken is doing a duet and trio singing workshop with our daughter Gina and Hal Krohn from our band.

How long have you been playing at the Folklife Festival?

Ken: Since the beginning, I guess, since the old days up at the [Lazy L] Ranch on Fickle Hill. I played with a bunch of groups, often the same people but with different names. They used to have a dance at the end of the festival with The Contra Band and my band, Swing Shift, on alternating years. When Maria was pregnant we played as Old and On the Way.

Do you consider yourself a folk musician?

Ken: I can accept that if someone else thinks I am, in a kind way. I guess there was a time when I kind of took offense at that description, but it wasn’t like I’d complain and tell them, “That’s not what I am.”

Why would you take offense?

Ken: I guess I had a limited view of what folk music was.

What is it?

Ken: That’s kind of a hard question to answer. What is it? What isn’t it?

Maria: I’d say it’s music that “folk” play. For me, it’s a personal expression and a communal experience whatever name we give it.

Ken: There’s a worldwide folk music, but in our country today it seems like old country music is folk music. It’s different from the high volume electric kind of thing, the city thing. That’s one way to look at it.

So it’s quieter and acoustic?

Ken: I’d say acoustic-oriented. The first time Swing Shift played Folklife, Hal was playing electric guitar and he was the only electric player there. People were talking about whether that should have happened at all. In some way it seems like singer-songwriters are the truest of folk. I host the “Bluegrass Country” show on KMUD (Tuesdays 10 a.m.-noon) and Falling Rocks will play sometimes. People say, “Oh, that’s really good bluegrass music.” I don’t take offense, but I don’t agree. We’re not a bluegrass band.

As folks involved playing and as a business, do you think there’s been a resurgence in interest in folk lately?

Maria: I’ve been involved in the music business for 20 years, and I’d say it’s been happening all along. It may be more popular in Humboldt lately because people are pouring more energy into exposing people to it. The Folklife Society plays a role in that. But across the country it seems to be going very well, from our perspective.

Her Heart Wide Open

Georgia-born songwriter Joanne Rand says she followed “a long twisted path” before settling in Arcata, one that included recording eight albums over the course of just short of 20 years. She fits into the grand tradition of the political folky, a self-described “singer-songwriter, healer, mother, wife, activist,” a true “wrong-righter” who uses her powerful voice to rail against war and injustice in all its forms, but can quickly shift into lullaby-mode singing for her daughter Georgia, or sing the praises of the wild rivers she loves.

What will you be doing at the Folklife Festival?

I will be performing with my band, The Rhythm of the Open Hearts. It’s bass, drums, [electric] guitar, violin, myself on guitar and voice, possibly keyboard. We play anthems of transformation and personal power. I’ve been writing songs for 20 years. Make that 30 years. Lately I’ve been doing traditionals, adding verses and sort of twisting them to my own fashion.

What do you mean when you say traditional?

Appalachian tunes, Celtic tunes; I’m working on a Woody Guthrie tune right now. Sometimes I’ll refashion the lyrics; sometimes I’ll add a whole second half to the song. And I’m still writing my own songs.

Do you consider yourself a folk musician?

Well, it’s interesting. I just came from the Kate Wolf Festival; I opened for Dougie MacLean [a neo-traditional Scottish songwriter]. And I was questioning: Am I a folk musician? I like a little edge to the music, so I liked the folk music I heard there that had an edge to it. That doesn’t always mean louder, harder, faster. It’s authenticity that cuts through to the bone. There was this one guy, Tom Russell -- he was fabulous, just him and his guitar. His voice was quiet but it cut through. It was very real, no fluff.

Is that what you think of as folk?

No, that’s what I like. Folk music, to me, is ... God, that’s a hard question to answer. I’d say, traditionally it’s almost like the newspaper: It’s the storytellers, the bards, the historians, those who sing the praises.

You mean like the griot in Africa or the troubadour in “merry olde” England?

Right. Djali is another word for it.

Do you see yourself in that role?

I do. I see myself as a troubadour, a cultural pollinator. I’ve traveled for over 20 years, gathering ideas, spreading them and taking what I gather from others and weaving it into songs. It’s all in there. That’s what I’m doing right now, in fact. At Kate Wolf I heard a rendition of “This Land Is Your Land” around the campfire. It caused me to get interested in it and start weaving it into a song for Fourth of July, something I’ll sing on the Plaza.

Why do you think folk music, particularly this music from the Appalachian Mountains, has such a strong hold in a place like Humboldt County?

I couldn’t say why for Humboldt, but I know why for me. It’s because it’s our roots. Appalachian music came over from Ireland and Scotland, from the Celtic tradition. It’s tribal music, really. It’s instinctual. It goes beyond thought. It’s in our bones. I feel that. When Dougie MacLean picked up his fiddle, I knew the music was in my blood. It speaks to that part of me that’s beyond words, that’s deep inside. A lot of people who move out there are searching for their roots, and they find them in that music.

As promised, Joanne Rand played her altered version of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” on the Arcata Plaza on Independence Day, fitting it into a medley of sorts. She began with a song that seemed to be composed just for that day. As the opening act for the town’s “Fourth of July Jubilee,” she’d been asked to sing “The Star Spangled Banner,” which she agreed to do with some trepidation: She’s not exactly the flag-waving type. Strumming her guitar, she told of a conversation she had with her 81-year-old mother. “I asked my mama,” she sang, “if I should sing the National Anthem, and she said ‘Yes, yes please.’” The song goes on to question the nature of patriotism in a time of war and turns anthemic with a call to “take back our country.” With a “Star Spangled” snippet as a segue, she shifted into Guthrie’s classic, her band weaving in fiddle lines and electric guitar. She added a few lines of her own, pulled out some of Woody’s more obscure verses and turned it into a sing-along, the crowd joining in on “This land was made for you and me,” before she concluded, “It’s up to you and me.”

Was it folk music? Without a doubt. To borrow a phrase from one of our wrong-righters of the past, it was music “of the people, by the people and for the people,” and that’s really what folk music is all about.

The 29th Humboldt Folklife Festival is July 15-21, 2007. For complete schedule and tickets, visit www.humboldtfolklife.org or call (707) 822-5394. Tickets are also available in Arcata at The Metro, The Works and Wildwood Music, in Eureka at The Works and at the event at the Dell'Arte ticket office.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1