"... Lord, in the memory of all the saints who from their labors rest, and in the joy of a new beginning, we ask you to help us work for that day when black will not be asked to get in back, when brown can stick around, when yellow will be mellow, when the red man can get ahead, man, and when white will embrace what is right...." -- Rev. Joseph Lowery, in his benediction at the swearing in of President Barack Obama

The lamprey has existed unchanged for at least 360 million years -- almost since the time vertebrates started walking out of the water onto land. Sure, it has undergone minor diversification in size and habits, but overall it has remained the same: jawless, scaleless, boneless and long-bodied, with a cartilage spine and a suctoral disc -- a nightmare mouth -- whose ring of teeth is designed to latch onto prey and extract bodily fluids (though they don't all do this). It has changed the least of any vertebrate living today, and is one of only two jawless vertebrates -- the other is the hagfish -- that survived the major extinction events that obliterated less stalwart brethren.

In some places, like the Great Lakes, the lamprey -- specifically the sea lamprey, an East Coast species -- is a voracious, introduced monster to be destroyed. On the West Coast, however, the lamprey is a poorly understood being. And many of its species, after getting by famously for almost 400 million years, have experienced a rapid decline in numbers in the past 50 years.

This is not good. And for some people, such as the Pacific Northwest tribes who have eaten and celebrated the Pacific lamprey, specifically, for thousands of years, it is a calamity. What's more, if the lampreys go, some say that could have implications for the more charismatic fish in our streams and ocean, the salmon.

Jan. 20, 2009. Inauguration Day. Midday at the mouth of the Klamath River, north spit, the second good week of eel season. All is sunshine. It is, in fact, stupefyingly warm. You just want to lie down on the pebbly beach and nap. Watch the sea lions surf the waves. Keep an eye on the line of eelers standing at attention at water's edge, tending the curls of surf that crash into the broad, racing tumble of river.

Each man holds a carved wood stick in one hand, attached to a long, hooked wire for snagging lamprey -- which the Yurok and other local tribes call an "eel" because of its looks: long, tubular, sleek. But eels have jaws, unlike this creature. In Yurok, it is "kah-ween."

One young guy holds a cell phone in his free hand. Another's got a soda bottle. A guy in his late 40s holds a can of Bud.

The tide's running out, the best time to catch lampreys. The river's a bulging tube of green water, gaining speed as it headlongs into the waves; migrating lamprey, trying to swim into the river so they can work their way upstream to spawn, come close to the lips of the mouth, the sandspits, to avoid the fast water.

A caramel-and-white dog has descended to the beach from the steep north bank at Requa, where some houses are, and is as avidly studying the waves as the men with hooks. He's way more hyper and undisciplined, though -- races up and down the sand, dashes into the waves barking and biting at them, then bounds ashore to chase and nip at the shadow of an ambling human.

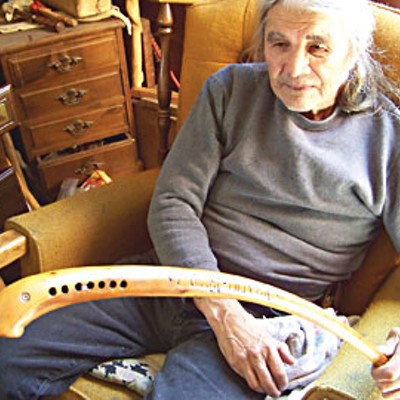

Merk Oliver, a Yurok elder, fisherman and renowned carver of beautiful eel hook handles, often from yew wood, stands back, watching. He begins tossing rocks into the surf for the dog to attack. If it's a big enough rock, the dog dives for it, snout submerged, teeth blindly vying for a grip. Pebbles he just whirls after and then just as quickly whirls away from to beg for another. And another.

"Go on, get it!" Oliver tells the dog. He throws another pebble; the dog catches it with his teeth -- "clack!"

An eeler comes up from the water's edge and points to the young guy with the phone glued to his ear -- that's Cliff Moorehead, he says; he's hooked nine lampreys so far, more than anyone today, and five or six of those before daylight.

"I had a thousand eels in my smokehouse one time," says Oliver. That was when his long hair was still black. When there were more eels. He's 79 now, gray, the oldest eeler out here. "My cousin and I were down here by ourselves and the eels were everywhere. I had a dog, and he had his own pile going."

Down in the surf, Moorehead darts forward, stabbing the hook into the water. He spins around, swinging the hook high with a slick, gray-white lamprey twirling around it, and races up the beach swinging the stick in a motion intended to keep the creature attached by centripetal force. It falls to the sand; Moorehead flips it back onto the stick and swings it, still walking. The whole time, he's talking on his phone. The other men tease him about it.

"I missed one earlier when I was on the phone," Moorehead says. "I was pissed off."

He drops the lamprey into a depression in the sand. It wriggles and tries to glide away; it looks like a friendly miniature jetliner, over two feet long and gleaming with seven little portholes. Except with a fringe of fin from midback down to its tail. And a rather sweet face with large dark eyes.

Moorehead opens a squirming black bag, picks up the lamprey, wraps his other hand around it and sweeps the slime and sand off of it, then drops it into the bag to join the others.

"You can trade and barter these things," says Oliver, watching Moorehead work. "But the white people consider these trash fish. They don't know about eels. Most people, they don't give a damn about eels. But they keep you alive. Salmon, eels, they were put here for a purpose, to keep you alive, right? And it just so happens that Yurok people were put here, right here."

He falls quiet. Tosses more rocks.

So, did he watch the inauguration of Barack Obama this morning? Yes, says Oliver, he did.

"I'm impressed by that man's intelligence, and by his words," he says. "I was touched."

And what did he think about the Rev. Joseph Lowery praying for the day "when the red man can get ahead, man, and when white will embrace what is right"?

"I think that was great," Oliver says, smiling.

The waves wash in, out, dragging sand. After awhile, he says, "I always wonder why people ask, ‘Why do you like eel?' Why? It keeps us alive!"

The caramel-and-white dog barks. Oliver tosses another rock.

In the sterile confines of a windowless meeting room, Damon Goodman, a fisheries biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Arcata office, places on the table a couple of examples of what might amount to hate speech in the underwater world.

One is a yellowed pamphlet from 1947 with the title, "The Menace of the Sea Lamprey."

The other is a copy of a Times-Standard article from several years ago, headlined "Groups push feds to protect bloodsucking lampreys." The accompanying photograph shows a pile of entwined lampreys, not exactly a pastoral scene.

Menace. Bloodsucking.

"It definitely puts a negative connotation on lampreys," says Goodman. "You know, lampreys need a PR agent."

The lamprey's bad rap originated in the Midwest, where sea lampreys decades ago swam from the Atlantic Ocean into the Great Lakes through shipping canals. The invasion wreaked havoc on the sports fishery, as the adult lampreys sucked onto fish with their toothy mouths and rasped holes into them to feed.

"So suddenly all of your game species in the Great Lakes started showing up with these big holes in them," says Goodman. "And people did not like that much. And a lot of the effort that was put into learning about sea lampreys was to get rid of them. And so a lot of what we know about lampreys to date comes from sea lampreys."

Which is to say, not much is known about our region's lampreys. And that monster stigma has latched onto them, even though the lampreys found on the West Coast are native and have co-evolved with the other native creatures. But, says Goodman, because they're not a game species there's been very little financial interest in studying them.

"Fish biologists were actually trying to get rid of lampreys on the Pacific Coast," says Goodman. "One example is the Miller Lake lamprey in the upper Klamath basin. It's the smallest adult lamprey in the world, just a couple inches at maturity."

The native Miller Lake lamprey isn't anadromous -- it doesn't migrate from the ocean into freshwater to spawn, like many lampreys. It is endemic to the Klamath Basin, meaning it occurs nowhere else in the world. In the 1950s, Miller Lake became a popular sport fishing area and was stocked with non-native salmonids -- who ended up with unsightly holes in them that turned off sportsfishermen.

"And so they started this aggressive plan to extirpate the Miller Lake lamprey from Miller Lake," says Goodman. "They poisoned the lake using rotenone. They dumped enough stuff in the lake so that no fish were found in it for years to come. They also built a barrier at the outflow of the lake, so no lampreys could make it into the lake."

The Miller Lake lamprey was thought to have gone extinct. But a few years ago a population was found in a nearby drainage. Now the barriers have been removed and the state of Oregon has embarked on its first-ever non-game fish conservation plan, to protect that lamprey.

Interest in conserving other lamprey species in the West has grown, too, as overwhelming reports from tribes and others indicate their numbers have plummeted. The Bonneville Power Administration and numerous groups have funded lamprey research in the Columbia River Basin since the mid-1990s. Idaho has a conservation plan for lamprey. And in 2003, 11 conservation groups -- including Friends of the Eel, the Environmental Protection Information Center and the Northcoast Environmental Center -- petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Service to list four Pacific Northwest lamprey species under the federal Endangered Species Act.

The petition said the species -- Pacific lamprey, river lamprey, western brook lamprey and Kern brook lamprey -- suffered from impacts similar to those affecting salmon caused by dams and diversions, poor agricultural and forestry practices and rapid urban development. It said the species had either disappeared from some streams or dropped from tens of thousands in number to less than a hundred in some cases. The petition noted that yet more species may need protection in the future.

The Fish and Wildlife Service rejected the petition. But it pledged to work on lamprey conservation. One major effort is the Pacific Lamprey Conservation Initiative begun in 2007, aimed at developing a plan to learn more about the species and restore its populations and their habitats.

Well, says Cliff Moorehead, shouldering his bag of eels, time to go home. "My girlfriend is hungry," he says.

Moorehead, who's 23, has been eeling since he was 10. "My neighbors like ’em," he says. "They all see me cleaning ’em and get excited."

"It's good to be generous," agrees Oliver. "In this way of life, you give and you receive." He pauses then adds, "People are too selfish anymore."

Moorehead leaves. "Eel can feed a lot of people -- even merk," says Oliver. Merk is Yurok for the blue heron, Merk Oliver's namesake. "If you take merk, for example -- he'll wait till everyone's gone, and then you'll see him over there, blood all over his beak. He'll throw the eel up into the air to shake off the sand and get it going down his throat."

Oliver says that when he was born, his great-grandmother looked at his long arms and said, "Merk. Merk."

"Merk is a known fisherman," he says. "Somehow or other, I became a fisherman. But anymore, as you get older -- to do this, you have to have swift reflexes."

Sea lions and seals, and many people, love lamprey. Ospreys eat them. Their meat has a higher concentration of protein than salmon meat. More oil, too. Some people think a healthy lamprey population is a buffer for migrating salmonids -- a sea lion will go for a fatty, meaty, slower lamprey before it chases the salmon, they say.

Eelers say the lamprey doesn't taste fishy. But white people often describe it as too rich and sweet.

Oliver lists the ways an eel can be prepared: brined, fried, cooked on rocks right here on the beach, baked, barbecued on a stick, dried, smoked. "I like ’em half smoked and then baked," he says. "Oh, they're delicious that way."

Pacific lamprey, the largest of the lamprey species in the West, is especially important to Pacific Northwest tribes; historically, it has filled the nutrition gap between salmon runs. It has a wide range, occurring from around Point Conception in California all the way into Alaska and the Bering Sea and across into northeastern Asia. Locally, explorers named the Eel River after the once-massive lamprey migrations (it still has lamprey in it). Now, with the lampreys' decline, some rivers have restrictions on their catch. On the Klamath, there are no catch limits. There also have been no monitoring programs, no concerted effort to track their numbers. But the Pacific Lamprey Conservation Initiative may change that.

"They aren't listed, and that's one of the coolest parts of this conservation initiative effort -- here we have biologists working from Alaska down to California, showing up and talking about these lamprey conservation issues, all outside of any regulatory framework," says Goodman, who is the initiative representative for the Fish and Wildlife Service's California-Nevada region. "For the American people, and taxpayer dollars, this is much less expensive than going through a listing process. ... And, it's tribes and non-governmental agencies, too -- whoever wants to participate."

One study Goodman's office is working on now is looking at mercury concentrations in Pacific lamprey juveniles in the Klamath Basin. Historic mining practices introduced high amounts of mercury into the system, Goodman says, and the mercury settled in the sediments. There've even been health advisories not to eat fish from Trinity Lake.

Pacific Lamprey juveniles, called ammocoetes, are tiny, wormlike larvae without eyes or a mouth that spend up to seven years burrowed in river sediments filter-feeding. Goodman says preliminary evidence shows these ammocoetes accumulate a vastly greater amount of mercury than even freshwater mussels, a much longer living filter-feeder. That means they might serve as an indicator species to learn more about the distribution of mercury within the Trinity-Klamath system.

Another project Goodman worked on, with the Karuk Tribe, was developing an identification key to help biologists distinguish between all of the lamprey species in the Klamath Basin.

Down at the mouth of the Klamath, Merk Oliver studies the waves as they rush up the beach then retreat, dragging millions of tiny colorful grains with them.

"That ocean is a busy guy," says Oliver. "He piles up the sand here."

A bigger wave than usual comes in, pushing river water with it, and washes over the feet of even the non-eeling bystanders.

"You know what they say about the Klamath River, don't you?" Oliver says, his eyes twinkling with a half-serious mirth. "Once you get your feet wet in the Klamath, you'll always come back."

Actually, as far as Pacific lamprey are concerned, it isn't known whether the same individual that is born, say, in a tributary to the Klamath, returns as an adult to that same spot. Not much is known about Pacific lamprey once they're in the ocean -- what they eat, or where they go. It is known they feed on a variety of marine mammals and fish, finding a host and probably getting dragged all over the place.

Goodman, for his master's thesis at Humboldt State University, conducted the first-ever genetic survey of Pacific lamprey, the results of which were published in 2008 in the Journal of Fish Biology. He wondered if Pacific lamprey exhibit spawning-site fidelity, like salmon who return to the stream they were born in. Such salmon show high levels of genetic differentiation among populations -- indicating homing to the natal stream, and a consequent low gene flow between populations, and more local adaptations.

Goodman found scarce genetic differentiation among the Pacific lamprey populations he studied -- and that suggests they don't return to their natal streams. One theory is that perhaps, rather than following the unique scent of a specific stream the way a salmon does, Pacific lamprey follow a universal scent put out by all juvenile lamprey. But there's still too much unknown to say for sure.

More, but not enough, is known about lamprey habits in rivers. And it is known that the Klamath Basin has the highest diversity of lamprey species in the world -- five identified so far, and more possibilities. Two are endemic, found nowhere else -- the freshwater-only Klamath River lamprey, found in the Trinity and some tributaries, and the Miller Lake lamprey.

Another interesting one is the Pit-Klamath Brook lamprey in the upper Klamath Basin and the Pit River. It doesn't eat once it becomes an adult. It filter-feeds as an ammocoete, then grows weak eyes and teeth and spawns immediately.

The Pacific lamprey, the largest of them, figures significantly in Yurok, Karuk and Hupa cultures and diets. The Yurok even have a story about how it lost its bones; a good rendition of it is in a report by Robin Petersen, who as an anthropology graduate student at Oregon State University recently spent a couple of years living with the Karuk and Yurok tribes learning about lamprey. A Yurok elder told her the story:

"Sturgeon was drumming for Eel during the betting and Bullhead was drumming for Sucker. Eel and Sturgeon lost everything they had, so in the last game they put up their bones and lost. This is why Sucker and Bullhead have so many bones and Eel and Sturgeon have none. Sturgeon is still going up and down sucking on the bottom looking for enough gold to buy back his bones."

Petersen notes that this story highlights "the inter-dependency of all species in the Klamath River."

The eelers watch the waves. The sea lions hang back, heads above water, watching the shore. They dive, become black oval shapes gliding through the heaving green.

"I never did like to hate," says Oliver, eyeing them. "But that's one I hate, the sea lion. And the harbor seal. They tear up the fish, they tear up our nets."

"There's no stopping them," says Oliver's friend and fellow eeler Jimmy Donahue.

Except with a bullet, he adds; but the deterrent kind of bullet, not the killing kind, says someone else.

A jet ski towing an empty rescue stretcher suddenly bursts through the river's mouth, bouncing on the tumbling current into the choppy surf, a guy in a wetsuit maneuvering. Sea lions pop up tall, one after the other, as the jet ski passes. The gulls huddling on the tip of the south spit lift into the air, foray over the water, then whirl back to land and re-fold themselves into a huddle.

"He's crazy," says an eeler, sounding like he wouldn't half mind being out there too.

His adrenalin's gotta be flowing, says another.

The water advances, recedes.

Oliver, who now has an eel hook in his hand, watches the waves intently. He's still thinking about respect. "As I see it, our people used to be very giving," Oliver says. "But in the last 30 to 40 years, we've lost that. We've become too selfish, too greedy."

He's silent again. Then says, "I'm at a loss for that. Our people were told to honor and respect. It's time to get back to that."

A lot of things disrupted his people's way of life, he says: explorers who killed them; miners who blasted into hillsides, releasing sediment into the rivers; two World Wars, which split up families as people left to serve or to work in factories and shipyards; timber companies who sprayed pesticides along the banks of the rivers to kill tree-competing weeds; the federal government, which took away the native peoples' fishing and hunting rights -- resulting in too many sea lions and seals, some say, and prompting tribes to battle in the 1970s to regain their fishing rights; and general pervasive prejudice.

"When I was a kid, they used to make up those movies about cowboys and Indians," Oliver says. "Oh, I used to get a thrill out of them. Cowboys coming in, and they get saved from the Indians -- we got a kick out of it." He laughs. "And here it was the Indians that needed getting saved."

When he was 11, says Oliver, he was shipped off to a federal government-run Indian boarding school in Salem, Ore., called Chemawa. "I ran away a couple of times. They gathered us up, a whole bunch of us, and took us away. I never did care for that, or respect the government for what they did to the people here. But then, hopefully, there could be change now, since Mr. Obama got in here."

When it's 9 to 11 years old, and up to 30 inches long, the adult Pacific lamprey migrates from the ocean into the river. On the Klamath, it may come in the mouth anytime between November and April. Traditionally, it would begin arriving in the mid-Klamath by spring. A Pacific lamprey may travel hundreds of miles upstream to spawn, until it hits a dam or a fish ladder it can't pass -- it can't negotiate right angles, and traditional fish ladders don't seem to work for it.

"One of the things we're learning about them is they have a much different strategy [than salmon] for overcoming obstacles in their migration," says Goodman. "They cannot jump, like salmon. They'll use their suctoral disc -- they'll grab onto something, and rest. As they work their way upstream, they'll burst, and grab on, burst and grab on."

They'll even use each other, he says -- sucking on and leap-frogging over, forming a wedge up, say, a steep wall. Craig Tucker, who works for the Karuk Tribe, along the mid-Klamath, says sometimes you can hear them inching their way upriver.

"They'll hook their mouth on a rock, squinch their body up, then lunge," Tucker says. "And they do it at night and you can hear them -- it has to be in a riffle, not too loud -- a weird chirping sound."

Toz Soto, a fisheries biologist with the Karuk Tribe, says Karuk eelers wait for signs of spring to tell them it's time to eel.

"It has to be as dark as possible," he says over the phone, from his office in Orleans, a few days after the inauguration. "A warm spring night with a new moon is the best time to harvest lamprey up here. April is the best time, maybe March if warmer. The tribal members here have environmental cues that tell them that the lamprey are in the river: crickets chirping at night, or dogwood blooming. Frogs."

The eeling technique at mid-river is different from that at the mouth. Eelers will use sticks to pry lampreys from the rocks they've sucked onto to rest, or they'll place baskets in the river to trap them.

Petersen's research found that traditional eelers have noticed not only declines in the numbers of lamprey in the river, but changes in where and when they show up.

"We can attribute that decline to some of the same reasons salmon have declined," says Soto. "Blockage to fish passage around dams, entrainment in [irrigation] diversions -- very few of the fish screens designed to prevent salmon from being entrained have the right specs to prevent lamprey from being entrained. Lamprey juveniles, they're so small that you can barely identify them with your naked eye. They'll fit through a window screen."

The trouble is, Pacific lamprey spend a long time in that vulnerable larval stage. The adult lampreys will dig a nest in fine gravels, moving big rocks out of the way with their mouths. Then the female will deposit over 100,000 eggs and the male will fertilize them, after which the adults die, their marine-enriched carcasses becoming nutrients for others in the river. A couple of weeks later, little ammocoetes emerge from the redds, not more than a centimeter long at first, and drift until they find fine, oxygen-rich sediment to burrow into. There they stay -- eyeless, toothless -- filtering the water for food (and cleaning the water, notes Goodman), until something dislodges them and they float until they can burrow in again. They do that for five to seven years before they morph, growing eyes and a toothed sucking disc for a mouth, and begin making their way downstream to the ocean, where they'll live a few short years as "bloodsucking" adults.

"And so, because they spend that much time in the freshwater environment, they're highly dependent on consistent, good conditions of the stream," says Goodman.

Soto says Karuk fisheries biologists have noticed strandings of juveniles after the start of irrigation season, when flows might go down abruptly -- but also, he adds, after a natural event such as a freeze that halts a spring snowmelt.

"At Iron Gate Dam, prior to 2002, they didn't have flow-ramping requirements, and they could drop the flow substantially without ramping it down through time, and we were noticing a lot of lamprey strandings," Soto says. "And now they have a ramping rate based on protection of endangered coho, and de facto that's probably helping lamprey. But we don't know."

Dams cause other problems. In a free-flowing river, natural depositional areas will form as sediment settles out, forming perfect lamprey-rearing habitat.

"Below Iron Gate Dam, we have very few depositional zones that are dynamic, that have sediment transport upriver and downriver," Soto says. "Instead, what we have are these depositional zones that are covered with algae and consist of decaying, dying plant matter that becomes this kind of anoxic muck, meaning zero oxygen. So you're not going to have lamprey there. You will get leeches."

The tribe is also worried about impacts to lamprey from gold mining suction dredges, and has been trying, along with conservation groups, to rewrite suction dredge regulations to protect lamprey and other species.

"The suction dredges take sediments and run them through the sluice box and lamprey are very vulnerable to that," Soto says.

Recreational miners counter that their dredges serve as calm refuges for lamprey and other fish -- and they have pictures to show it. They also say they remove the mercury from the sediment they dredge up, making the river cleaner.

A flock of terns swarms above the rocks on the north bank, including Oregos -- the one that Yurok legend has it is a woman with her legs folded, a baby on her back and a basket she's making in her lap. When she repositions her legs, the mouth of the Klamath moves, rearranging the long sandspit between the Klamath River estuary and the ocean.

That happened this year, says Bob Ray, a genial 31-year-old Yurok with long, black and a youthful, calm energy. Last year, he says, and for several years before that, the river mouth had burst through the sandspit next to Oregos. This year, the river mouth shifted south, creating a long south spit and a shorter north spit.

"That was pretty neat to see," he says.

Ray, who hangs nets as well as works for the Yurok fisheries program, grew up at Wau-kell Flats, upriver. He's been eeling since he was 10.

"You lived here, you eeled," he says. "I remember one night we were eeling, me and my cousin -- we were about 12 or 13 -- and the beach was split like it is now, and people had fires everywhere down here. We had three gunnysacks full, a hundred eels in each. I remember we put our hooks down -- we were tired -- and then we grabbed more eels with our hands. We gave a gunnysack full of eels away to an elder -- his name was Glenn Scott. Now, there's not even close to that many eels. It's pretty sad, too. It seems like every year it declines. Of course, every Indian would blame it on the white man. But I don't like to act that way...."

Even so, Ray sounds hopeful as he talks about watching Barack Obama on television this morning, getting sworn in as President.

"Forty-three presidents and finally something's changed," Ray says. "I used to joke around about the ‘white man's world'. Well now we have an African-American president."

Ray says at least one of his kids is interested in carrying on the eeling tradition. "I got my eye on my youngest, who's 5, to do all my fishing for me when I'm older," he says, smiling. "He's more like me. He's just that kind of kid -- more outgoing, traditionally. He loves snakes, frogs and lizards. He's just the outdoorsman, I guess."

The boy has been down to the spit a few times already to watch the older folks eeling. But he'll have to wait a few years before it's safe for him to brave the dangerous surf.

Comments (6)

Showing 1-6 of 6