- Moby-Duck

Some books tell a complicated story so engagingly that every few pages bring another grin of discovery, a mental "Wow, how cool is that."

Moby-Duck is one of those books.

Before you've finished it, you'll know about container ships and sea ice, childhood and toys, the six degrees of freedom and the ache of a father for his toddler son.

You'll visit a plastic sand beach, an aging Chinese toy factory and a largely empty looking stretch of ocean that's become known as a Garbage Patch of the sea.

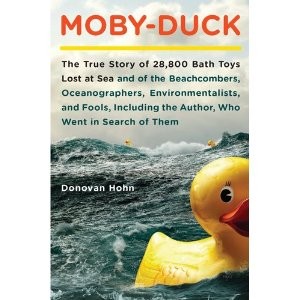

The gentle whimsy of this very intelligent book begins with its cover image -- a bright-eyed yellow plastic duck bobbing across the waves.

Its subtitle promises: "The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea, and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists and other Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them."

Author Donovan Hohn is no fool, but part of his charm is that he's more than willing to suspect himself of it.

When the book opens, Hohn is a schoolteacher and sometime magazine writer who gradually becomes seduced by the saga of those floating bath toys -- duck, frog, turtle and beaver -- that have fallen off a container ship.

Over time, as his first child is born and begins to talk, Hohn chases the tale of the toys: where they came from, where they went, how they disintegrated and what they can tell us about plastics in the sea.

In this, he is as rigorous with his subject as he is with himself, pointing out weak assumptions and sketchy data.

He pieces the story together on separate trips, often on a shoestring, and writes about each foray as he goes. Parts of Moby-Duck were printed first in Harper's, Outside and the New York Times Magazine, and sometimes the seams between magazine article and book-length work are poorly stitched, leaving awkward bits of repetition.

Largely, though, the mash-up works. Like a beachcombing kid running up with fresh wonders, Hohn constantly digresses from his central plastic theme. The hoax memorialized in Strait of Juan de Fuca, the leather-heavy diet of doomed arctic explorers, the trick for telling a fulmar from a gull, the idea of wilderness in a Wallace Stevens poem -- they're all part of the journey.

This is a language-lovers book, rich in passages that beg to be read aloud. Bright red and blue wetsuits hanging to dry "looked like melting superheroes." Of sailor and plastics pursuer Charles Moore, Hohn writes, "his heavy-lidded eyes and wrinkly neck give him the aspect of a sun-drugged tortoise." And of the iconic duck: "What misanthrope, what damp, drizzly November of a sourpuss, upon beholding a rubber duck afloat, does not feel a Crayola ray of sunshine?"

Comments