As the jury trial for the civil suit Kathryn Miller v. the Trees Foundation puttered to a start last week inside Courtroom 3 at the Humboldt County Courthouse, Shunka Wakan — a key witness for the plaintiff — spent mornings sitting on the hard wooden benches in the long hallway outside the courtroom. During breaks, Miller's attorney Linda Mitlyng, would come out of the courtroom to join him. But otherwise, as other people and their legal affairs swirled around him in a warm, odiferous bath of humanity, Shunka sat alone. Or, sometimes, he stood alone, straight-spined, his small, stocky body swallowed by the huge, stiff blue suit out of which his newly shorn, razor-scraped bald head poked vulnerably — as if, at any moment, the suit could gulp once more and he'd disappear completely. Always, he clutched a paper folder with a wolf's face on its cover.

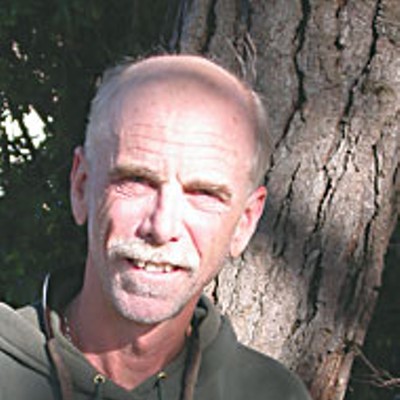

The North Coast Earth First! Media guru had shaved off his woolly rust-tinged brown hair and beard the night before jury selection started, after discussing it with attorney Mitlyng. Now, it took an uncertain moment to recognize him. Then, of course: Shunka's light blue eyes in the pink-pale face, Shunka's closed-lip smile, Shunka's trademark husky murmur, “Mm-hmm, for sure,” in response to a comment.

In Courtroom 3, the amiable but no-nonsense Judge Christopher Wilson's domain, the fate of a $185,000 donation dangled. Would the plaintiff, donor Kathryn Miller, prevail in her claim that the defendant, the Trees Foundation, was not in fact the intended recipient of her generous gift? That Shunka Wakan's NCEF! Media Center and the treesitters were? Or would the Trees Foundation convince the jury that, in fact, the money was intended all along for Trees, with no instructions attached for funneling it elsewhere? Richard Idell, left, who is defending the Trees Foundation against a lawsuit filed by Kathryn Miller, confers with Doug Wallace, community support coordinator for Trees. Photo by David Lawlor.

In her opening arguments, Miller's attorney, Mitlyng, said the case came down to “fraud and broken promises.” “She believed [Trees] would hold [the money] in trust, for the benefit of North Coast Earth First!” said Mitlyng. The defense's attorney, Richard Idell, countered in his opening argument that the donation was an unconditional gift and Miller never wrote letters of instruction — as Miller claims she did. “Ms. Miller ... didn't do anything. She took the check [from her mother's estate] and flipped it over and wrote on the back, ‘Payable to the Trees Foundation,'” said Idell.

Miller's claim sought the return of her $185,000, plus interest.

Out in the hallway, Shunka waited to tell his side of the story. Maybe he thought about the magical donation that never materialized, and now probably never would. Maybe he thought about the other times he'd been in this courthouse — dozens of times, along with other activists, often before Judge Wilson, answering to charges of trespassing and other forms of civil disobedience in the woods. Likely, he wondered when they were finally going to call him in to testify — it was taking forever in there. He'd even sent out an e-mail prematurely to the several hundred subscribers to his NCEF! online group erroneously announcing he would be first up to testify.

By the end of Friday's court session, Miller was still on the stand. Perhaps Monday it would be Shunka's turn. Whenever it was, he would be testifying on Miller's behalf; but he wasn't a party to the lawsuit. And in the end, after hearing all of the evidence, the jury would be determining who was telling the truth about intentions and letters of instructions. Shunka was just there to provide context and evidence in a contract dispute.

But to a number of forest activists, including a half dozen or so who appeared in the audience last Friday to watch the trial unfold, that context matters more to them than the legal questions. They say this lawsuit has placed a strain on the environmental community that could do as much damage as an ill-felled redwood that takes down other giants in its descent. They disapprove of the lawsuit, and they blame Shunka for it. And, they say, it's just another example of how Shunka has commandeered the North Coast Earth First! identity and used it for purposes that nobody else in the amorphous but consensus-driven local Earth First! movement has agreed to.

“For a lot of us, when we read about the lawsuit, this is kind of like Shunka on trial,” said long-time forest activist Deane Rimerman last Friday, calling from Olympia, Wash. “And, to what extent is he worthy of that money?”

Kathryn Miller wanted her money to go toward saving trees, she said on the witness stand last Thursday. The slender 59-year-old was dressed in a pink print skirt and white sweater, with her gray-streaked dark hair pulled back into a neat, thin braid tinted slightly green. (Little did the jury know that Miller had spent the night in jail, in blue jail duds, and then had been “dressed out,” in court lingo, in her street clothes before being escorted into the court by the bailiff. Miller had been arrested the week before, on Sept. 17, when she arrived in civil court for the pre-trial readiness hearing; according to the misdemeanor criminal charges filed against her, Miller allegedly had made annoying phonecalls to Barbara Ristow of the Trees Foundation all hours of the day and night.)

On the stand, Miller described how she became an activist. She remembered how, when she was a child in Orinda, her mother decided to stop spraying the beautiful oak trees on their property after reading Rachel Carson's Silent Spring . “And then, when my son was 9, we were watching the news on TV about the Chernobyl nuclear power plant meltdown. And my son said to me, ‘I wish I'd never been born. I don't think I'll get to live a full life.'”

She protested the building of the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant. She started a peace action group in the late 1980s in San Jose. She did nonviolent protests at the Nevada Test Site. And in 1990, she came up with some of her fellow protestors to help set up the camp for Redwood Summer, and to take part in demonstrations. She's been on and off involved in Earth First! actions in Humboldt ever since, she said, including huffing in supplies for treesitters and huffing out their garbage. She'd also, at one point, bought a condo in Arcata.

In 2004, Miller sold her condo and bought an acre of farmland, already planted with coffee, in Guatemala. She put in fruit trees to shade the coffee. That same year, her mother, who lived in Sonoma, died. “The last time I saw her was in 2003,” said Miller. “She told me when she died, she was going to leave me some money. I told her I'd use it to further my work for the forest. And she was pleased, because she loved the treesitters and the forest.”

Shortly after learning of her mother's death, Kathryn Miller sought out Shunka Wakan in front of the food co-op in Arcata, where he “tabled” to raise funds for the North Coast Earth First! Media office — selling T-shirts, and stickers, offering pamphlets, accepting donations. She'd known Shunka for about five years, she said.

“I said to him, I was going to inherit some money: What was the best way to get that to the North Coast Earth First!?”

In the spring of 2005 , Shunka Wakan was floating above the treetops. “I was so excited,” the 32-year-old said in an interview a few weeks ago, sitting inside his tiny but colorful North Coast Earth First! Media office in Arcata, walls covered in art and topo maps — including one of Buckeye Mountain, where in 2000-2001, during the “Mattole Free State” action, Shunka and others hiked 14 miles through waist-high snowdrifts to save trees.

Kathryn Miller, he recalled, had come up to him excitedly as he walked along the sidewalk outside the Arcata Co-op and said, “I just donated $185,000 to North Coast Earth First!'”

She'd talked to him the year before about making the donation — she'd said she was anticipating an inheritance from her mother's estate, and she wanted to make a big donation to his group. He'd told her to make it through the Trees Foundation, which handled the NCEF! Media office's finances through an arrangement that had been established years ago. (The Trees Foundation is an umbrella organization formed in 1991 to assist smaller environmental groups. As a 501(c)3 nonprofit, it can accept large, tax-deductible donations on behalf of affiliates, and provide professional resources. And it can lead large campaigns, like the one to save the Headwaters Forest back in the '90s.)

Well, now she'd finally done it.

Miller and Shunka agreed to meet at Fiesta Café in Sunny Brae, so she could tell him how she wanted the money spent: She wanted, straight away, for someone to organize a mediated workshop for the local Earth First! activists on ageism and sexism, issues she thought were fracturing the movement. And, she wanted the bulk of the donation to help support the forest activists who blockade logging roads and hunker up in ancient redwoods to fend off loggers' saws.

Not long after, Shunka was on his way to have lunch with some folks from the Trees Foundation, where they'd talk about Miller's wishes.

“Our media outreach was going to get a big boost,” Shunka said. “The donation would keep the EF! office going for many years. So I walked into the Wildflower Café feeling elated, thinking we got all this money.”

Barbara Ristow and Doug Wallace of the Trees Foundation were there. “I was super excited,” Shunka said, “and I said, ‘This is great, this big donation. Isn't it wonderful?' We ordered food, and still I'm all excited, talking about the money, but I notice they're looking nervously at each other. [Finally], they said, ‘Well, we're just shocked that you think this money was for you.' And I was like, ‘I just met with the donor, and that's what she said.' And they're like, ‘Well, let's go ahead and plan the workshop and deal with that later.' I remember that, because it put me at ease.”

After that, Shunka said he gave Trees a list of people he thought might benefit from the mediator-run workshop. “Some were people I knew had beefs with me, but I was willing to bring 'em into the circle and talk about it.”

According to some vague accounts, the workshop was a disaster. One person who was there claims that Shunka, at one point, pounded his fists on the floor, blustered, then got up and stormed out, yelling as he walked away. Shunka says that's overblown.

“The letter from Kathryn Miller to Barbara Bristow said she wanted the mediation to be a safe place, safe to be emotional,” he said. “And I think people are saying ‘I freaked out.' The freak-out reports are exaggerated. It's just part of this ongoing character assassination. People say I was ‘red-faced.' But my face is naturally red.”

In late 2005, while Shunka was in Seattle, a friend called him from Arcata to say a woman had come by asking for the office key. She had a list of equipment she wanted to take away. The friend didn't give her the key.

When Shunka got back from Seattle, he discovered his reimbursement funds from Trees had been “frozen.” He also learned about a letter someone in the NCEF! movement had circulated for signatures and then sent to Mark Knipper, who handled the Trees Foundation transactions for the NCEF! Media office. It said, in essence, “We don't want Shunka running EF!”

“I called the Trees Foundation,” Shunka recalled. “I was sick, it was the middle of the winter, I'm trying to table, it's raining, it's cold. And Barbara Ristow told me, ‘You just need to have a meeting [with the other Earth First!ers] and come to a group consensus on what the Trees Foundation funding should be used for.”

The meeting never happened — nobody could agree to meet, said Mark Knipper, also in an interview last week. Knipper is a social worker and a long-time activist who had been the contact person between Trees and NCEF! Media. “So it ate itself,” Knipper said. “And although I'm former Navy, a mariner, I said I'm not going down with this ship. So I divorced myself from it ... and signed it all back to Trees.”

The NCEF! Media office was dropped from the Trees Foundation altogether.

Shunka and the NCEF! Media office never did see any of the big donation. Miller didn't even know that, he said, until she phoned him up in the summer of 2006, more than a year after she made the donation, to ask about a guy named “Jungle,” who had been reported as missing on the NCEF! hotline. Miller was spending much of her time in Guatemala now, where she was raising fruit trees; after she'd made her big donation, Hurricane Stan had struck — she spent the ensuing year mopping up the mess.

First, Shunka told her Jungle was still missing. Then he told her about the money.

“I said, ‘Yeah, they told me it wasn't for us,'” said Shunka. “And she said, ‘I meant for all of it to go to you guys.' She sounded real upset. And I was like, ‘I knew it! I knew it!'”

Shunka tried to sue Trees in small claims court, but it went nowhere.

Miller filed a claim against the Trees Foundation on Oct. 5, 2006, in Humboldt County Superior Court, seeking the return of the $185,000 plus interest so she could distribute the money herself.

And if she wins? “She may just spread it out more,” said Shunka. “She's got tree planting ideas. Maybe she could buy a grove. She'd maybe not give it all to Earth First! this time. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that Trees blew for us.”

On an uncomfortably hot afternoon last week, four forest activists who'd agreed to an interview for this story — Jeff, Shaggy, Sparrow and Farmer — sat on the ground at the Arcata Marsh next to a log bench on which a teeming crew of red ants worked a splintered notch. Someone had come along here in 1999 and carved a grouping of faces — bearded, grimacing, possibly mourning faces — onto the log and signed it Daniel. The carving had been drenched in red paint, and burnished by years of sitters.

“It kind of reminds me of the memorial for Gypsy,” said one of them. “With the red paint.”

Gypsy was the forest name of David Nathan Chain, who in September 1998, during an Earth First! action at Grizzly Creek, was crushed to death by a tree felled by an enraged logger. Farmer, actually, was there — he was just 16, but had a year of activism already under his belt. And Shunka was there — it was Shunka's first forest action.

Farmer, Shag, Sparrow and Jeff first made it clear that they spoke for themselves alone, although they participate in various forest defense affinity groups: Farmer works for the Mattole Wildlands Defense Group now, watchdogging the California Department of Forestry for new timber harvest plans, and keeping an eye on a Pacific Lumber Co. watershed analysis. Shag, who saw his first redwood about five years ago, helps keep the Fern Gully treesit village in Freshwater functioning. Jeff, who grew up in the high desert, and fell in love with the woods, works with the Nanning Creek treesit just outside of Scotia, as well as other groups. Sparrow, who was drawn to forest action because the cultural landscape was “like a folktale” he couldn't resist, is with the Fern Gully affinity group. These groups are all part of the Humboldt Forest Defense Association, a collective with a website but no formal structure.

The HFDA sprang into being six years ago — about the time the entity called North Coast Earth First! had essentially dissolved. It would take a book to describe that drawn-out dissolution — a book of lost causes, won causes, waning media interest, Judi Bari's death, Gypsy's death, ego-spurred squabbles, interpersonal catastrophes, a war overseas, hurricanes. And while the HFDA activists might still cherish the Earth First! name — the movement — in their hearts, it's now been further complicated by what you might call the Shunka effect.

“I still feel in many ways solidarity with the greater Earth First! movement abroad,” said Farmer. “But in this county, in this climate, if you say you're with the North Coast Earth First!, many people associate you with North Coast Earth First! Media.”

Shunka revived the North Coast Earth First! office around 2002. And he did what previous office managers had done — tabled, put out news releases, wrote articles for other publications. But it wasn't like the old days, in the '90s, when hundreds of people were getting arrested in forest actions and the jail support phone and legal resources were in constant use.

Shunka first worked in an office in Eureka, then later moved to Arcata. He called his outfit the NCEF! Media Center. For a time, he and other “affinity groups” tried to work together. But he alienated some people. He took over the North Coast Earth First! website. He controlled the North Coast Earth First! email list of 300 or more subscribers to the news alerts. He sent out press releases on his own.

“I felt the North Coast Earth First! Media Center was a unilateral effort on Shunka's part,” said Farmer. Whereas, in the old days, “spokespeople were decided on by the group. And if you wrote an article it was passed by everyone. I feel Shunka appointed himself spokesperson at some point.”

Many also claim they've been subject to a lashing anger from Shunka.

“I won't work with him because I pledge nonviolence in my actions,” said Shag. “I don't believe he pledges the same thing. He has exhibited violent behavior towards me and towards other activists in my presence.”

“He's a bear,” said Jeff, making claw-fists with his hands.

But the sad thing is, all of this infighting probably has done nothing to help the actual trees. And the mediation workshop Kathryn Miller wanted didn't fix matters. Now, there was her lawsuit.

“When I heard about this lawsuit, I thought, the Trees Foundation does not deserve to be attacked in that way,” said Farmer. “There's much bigger issues that need to be dealt with — with Maxxam and old-growth logging. ...If you look at Fern Gully and Nanning Creek (the Bonanza timber harvest plan), there's hundreds of old growth acres still standing whose fate is unclear.”

Shag put it more bluntly: “If [Miller] knew Shunka and wanted to get the money to North Coast Earth First! Media, she should've given it to Shunka. But if she was trying to get it to treesits and forest defense, then the money went to the right place.

“My problem is this whole representation thing. There's people in the trees — how do you know who to get the money to, to help them?”

Shunka knows that a lot of fellow activists aren't happy with his role in the donation dispute. He also knows how some people talk about him and say he's hard to get along with. “I'm just standing up for the truth,” he said. “And people don't like it. To me, it feels like a small clique of people who don't like me. I feel a lot of love and support in this community.”

He certainly doesn't come off right away as someone who's angry, or who lashes out, or who locks the office and doesn't let people in. Why, recently, he helped a young woman hook up with the treesitters so she could learn the ropes. (Shaggy said that's proof Shunka doesn't have direct connections with the people doing direct action; but you can't deny it's a connection.)

Shunka Wakan, in his North Coast Earth First! Media office on Samoa Boulevard in Arcata. Photo by Heidi Walters.

It's probably a bad idea to ask Darryl Cherney, one of the founders of the local Earth First! movement, what he thinks of Shunka Wakan, whose real name is Jason Wilson. (Shunka tells a story of how he was named by a Lakota medicine man on the banks of the Cheyenne River in South Dakota in 1995. “Shunka Wakan,” meaning “great dog,” is only part of it. There's a secret part after that — altogether, his name means “the humble man called horse.”)

“Shunka's a wingnut,” Cherney said over the phone last Friday, sounding cheerfully vitriolic. “I have a 10-verse song about Shunka.”

Here are the last few verses:

*Who's at the co-op spanging a donation

Shunka, Shunka

Who's got a lawsuit 'gainst the Trees Foundation

Shunka, Shunka

Shunka, Shunka

Who's gonna keep on fighting the fight

Shunka, Shunka

With four of his friends at swimmers delight

Shunka, Shunka

Shunka, Shunka (Shunka voice: It's the last of the revolution)*

There's no other word for it but “mean.” But Cherney and Shunka have history — not all of it sour. Cherney said Shunka laughed when he heard the song, at least the first time.

“I met Shunka in 1998,” Cherney said. “And I know he knew Julia [“Butterfly” Hill, whom Shunka had come west to find]. That was a good thing, helping Julia. That was good Shunka.”

Cherney had even pushed for Shunka to go to Houston to talk with Charles Hurwitz, whose Maxxam Corp. bought out the old Pacific Lumber company back in 1985 and quickly became the forest activists' number one villain. Shunka went.

But now? “The current status of Shunka and me,” Cherney said, “is that Shunka has sent me five or eight or nine e-mails threatening to sue me. Shunka is a joke.”

Cherney can talk for hours about the problems he's had with Shunka over the years. His main point, though, is what has Shunka done for the trees lately?

“My question is, where's your topo maps?” he asked. “Where's your wilderness preservation proposal? Where's your lobbyist team in Sacramento?”

It has to be that, on some level, even the people in the movement who don't like Shunka understand somewhat where he's coming from. So he's emotional. Passionate. Perhaps he's caught up so completely in the cause he can't let go. Or, who knows — maybe he's a phony, like he accused Knipper of being back in 2005.

But being a forest activist comes with perils beyond the obvious physical ones.

“I'm really trying to have compassion for Shunka, even though he's kind of attacked us,” said Susy Barsotti by phone from Laytonville a couple of weeks ago. Barsotti is president of the Trees Foundation board, and she says the lawsuit has held Trees hostage, unable to function fully. “I've been mystified and dismayed that he's participated like this in the suit. But Shunka witnessed Gypsy's death. And I think he may have post-traumatic stress syndrome. I don't think he's recovered from it. And that can affect your behavior.”

A number of people mentioned this, actually, about Shunka. And he often refers to Gypsy's death himself. In an article titled “What Luna has taught me,” posted on the website of Julia “Butterfly” Hill's organization, Circle of Life, Shunka writes: “I decided to commit to doing ground support after witnessing the death of David Nathan “Gypsy” Chain on September 17, 1998 ... I remember looking across the valley as we hiked up that day, seeing the rolling hills of forests and clear-cuts, and thinking out loud, “That's why we're here!” Seeing Gypsy's life taken from him, and then seeing the corruption and lies of the Humboldt County Sheriffs ... really opened my eyes to the situation our old-growth forests face.”

Later, he did ground support for Hill in her second year in Luna. And in the same article on her website, something else Shunka writes indicates how ready he was to devote himself to a cause: “Being on the support team was the top priority in my life, and I was happy knowing that everything else revolved around when I'd be needed for the next supply run. I never felt lost because I knew what I was doing. That was a feeling I had not felt in years, between feeling dissatisfaction with life in college, and then more dissatisfaction with life as a minimum-wage worker after college. Before joining Julia's ground support team I was unhappy, even to the point of tears, wondering if my entire life was going to be a minimum-wage nightmare ....”

Pure devotion, without benefit of a little hypocrisy, could drive anyone batty. Deane Rimerman, the activist from Olympia who said it is Shunka who is on trial, said it's not uncommon for intense, stressful movements like Earth First! to produce an army of walking wounded. And he's been around, in forest actions up and down the coast, for long enough to know; he was the one, in fact, who “got the maps and led the first hikers up to the hill” to the Gypsy Mountain campaign and Luna treesit.

“In the forest activist movement, there's very little that's rewarding,” Rimerman said. “There's a lot of post traumatic stress syndrome. All of us get it. Once you've been through the court process, and the jail process, and seen 1,000-year-old trees get cut down that you really cared about and thought you could save — it's devastating.”

That alone, setting aside the troubles with Shunka, could explain the many rifts that have occurred within the local EF! ranks over the years. Josh Brown, who moved to Humboldt in 1995 right before the peak of the Headwaters campaign, said one of the unique qualities of Earth First! is that it “is primarily a youth movement.”

“A lot of people that come through are young, are passionate — and it's a wonderful thing,” he said. They get thrown into leadership positions quickly — and then they get burned out. Many move quickly on to other things. Brown stayed in longer than most. “When I left [in 2001], I was 30 years old. And I'd been a full-time activist since I was 18.”

Paradoxically, said Brown, the youthful draw and the departure of seasoned activists leaves the movement with “no elders to kind of sit around and coach the [new kids].”

The movement also draws strong personalities, he said. Tenacious ones, too, like Shunka's.

“Shunka, I think he really does have a big heart,” said Brown. “And I think he does care for the forest.”

Last Friday, following the morning session of Miller v. Trees, a group of the Humboldt Forest Defense Association activists stood on the courthouse steps talking. The door opened, and Shunka walked out and down the steps toward the group. They didn't greet him. After a time, he tried to talk to one of them, Jeff. Jeff walked away. Shunka followed him, then stopped and talked to another guy. Then he stood alone again.

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4